Here we detail about the ten major economic policies which are followed in India and has played a major role in the growth of Indian economy.

And , the policies are: (1) Industrial Policy, (2) Trade Policy, (3) Monetary Policy, (4) Fiscal Policy, (5) Indian Agricultural Policy, (6) National Agricultural Policy, (7) Industrial Policies, (8) International Trade Policy, (9) Exchange Rate Management Policy, and (10) EXIM Policy.

Policy # 1. Industrial Policy:

The first Industrial Policy based on the mixed economy principle was announced in 1948 which demarcated clearly the areas of operation of the public and private sectors. This policy was revised in 1956 which laid greater emphasis on the expanding role of the public sector. This was in keeping with the Mahalanobis strategy of industrialisation embodied in the Second Five Year Plan (1956-1961).

Trade-related ISI strategy of industrialisation demanded control and regulation of the industrial sector. The basic instrument of control was given by the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, 1951, which provided the legislative framework for licensing of industrial investment in the country. The MRTP Act, 1970—another regulatory mechanism—aimed at controlling the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few big monopoly business houses. The FERA, 1973, was designed to control foreign investment in India. All these controls and regulations were consistent with the broad ISI policy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

India reached the crossroads in 1991 when unprecedented economic crises called for unprecedented changes in economic policies. Making a sharp departure from the 1956 Industrial Policy, the Government of India announced liberalised Industrial Policy on July 24, 1991. Instead of state-sponsored development, the new policy put emphasis on market-led development.

Indeed, this new policy takes a bolder step towards the process of deregulating the economy so that Indian industry becomes more competitive—domestically and internationally. This policy marks a great leap towards privatisation and liberalisation. It envisages disinvestment of government equity. The new policy has laid a red carpet for foreign direct investment. It is in line with the current economic philosophy of the government to liberalise the existing industrial and commercial policies with the objective of increasing efficiency, gaining competitive advantage and achieving modernisation of the economy.

Policy # 2. Trade Policy:

What should be the appropriate trade policy or commercial policy of a country? The issue was first raised by the classical authors. However, they were the champions of free trade. The two giant advocates of free trade—Adam Smith and David Ricardo—about two hundred years ago argued that free flow of goods and services, i.e., unrestricted trade, would be beneficial.

As a result of free trade, each country specialises in production in which it has a comparative advantage. This will enable each country to reap gain from trade. After the Second World War (1939-1945), commercial policy underwent a change when the wave of protectionism swept all over the world. It was argued at that time that though some trade is better than no trade, there is no reason to suppose that free trade is the best.

Trade under Free Trade:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The trade theory (both the absolute advantage and comparative advantage theory) assumes the existence of free trade. Here we want to explain how do free trade influence domestic production, consumption, and import. Such may be explained with the aid of demand-supply mechanism.

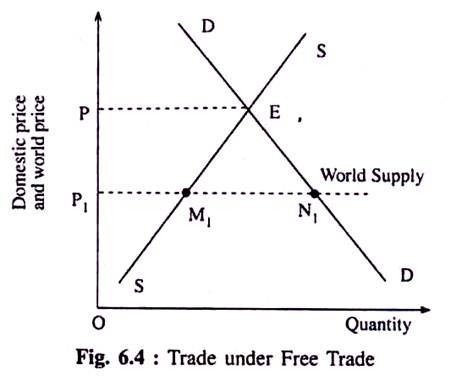

In Fig. 6.4, the curves DD and SS are the demand and supply curves of say, Indian consumers and producers, respectively. These two curves intersect each other at point E. Thus the pre-trade price prevailing in India is OP. However, as soon as this particular commodity goes outside the country where price is determined in the world market, it becomes lower than the domestic price OP.

Let the world price be OP, (<OP). Now in the absence of tariff and with the opening of trade, the price in India (OP) becomes equal to the world price (OP,). But, why? Since trade is free, the foreign country would then export in the Indian market where price is higher than the global price. It is because of competition between the countries price would then fall to OP, in the Indian market.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Note that at this lower price, Indian producers would reduce supply from PE to P1M1 while domestic demand would increase by M1N1. The horizontal line represents the supply curve for import. This is a perfectly elastic supply curve. Anyway, with the opening of trade, the supply- demand gap to the tune of M1N1 is to be met by imports from the foreign country.

The essence of the argument is that the strength of Indian demand for imports and supply of domestic good determine this volume of trade. In other words, it is the demand and supply that determines the volume of trade under free trade.

Free Trade: Arguments and Counterarguments:

International trade that takes place without barriers such as tariff, quotas, and foreign exchange control is called free trade. Thus, under free trade, goods and services flow between countries freely. In other words, free trade implies the absence of governmental intervention on international exchange among different countries of the world.

A new question thus arose:

Can protected trade cause a gain from trade? LDCs after the World War II, by imposing tariffs and duties, made an attempt to secure maximum benefits from international exchange of commodities. This kind of governmental intervention in trade policy is known as ‘inward-oriented trade strategy’ or ‘biased against trade strategy’.

But the last quarter of the 20th century saw the revival of free trade or ‘outward-oriented trade strategy’ all over the globe as protection failed to provide enough gains which the countries required. Actually speaking, a strong wind was then blowing in favour of free trade.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank also came forward to encourage the free trade philosophy. However, the debate between free trade and protection is yet to die down. In this section, we will touch upon the main issues of free trade and protection.

Policy # 3. Monetary Policy:

Monetary policy or credit policy concerns itself with the cost (i.e., the rate of interest) and the availability of credit to affect the overall supply of money. The hallmark of the RBI’s monetary policy in the 1950s was that of controlled monetary expansion. To supplement the process of macro stabilisation and structural adjustment programmes launched in mid-1991, monetary policy has been redesigned. Market-oriented reforms (such as interest rate liberalisation, entry of private Indian and foreign banks, development of alternative system of monetary controls, etc.), are being constantly made since monetary policy measures are continuous.

The Three Instruments of Monetary Policy:

The monetary authority controls the money supply directly and/or indirectly by altering either the monetary base or the reserve-deposit ratio. To do this, the monetary authority has at its disposal three main instruments of monetary policy: open-market operations, reserve requirements and the discount rate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Open-market Operations are the purchases or sales of government bonds by the Central Bank/monetary authority. When it buys bonds from the public, the money it pays for bonds increases the monetary base and thereby increases money supply. When it sells bonds to the public, the money it receives reduces the monetary base and thus decreases the money supply. Open-market operations are the most-often used policy instrument of the Central Bank.

Reserve Requirements are Central Bank regulations that impose on banks a minimum reserve-deposit ratio. An increase in reserve requirement raises the reserve-deposit ratio and thus lowers the money multiplier and the money supply. This is the least-frequently used instrument.

The discount rate is the interest rate that the Central Bank (BOE) charges when it makes loans to banks. Banks borrow from the Central Bank (CB) when they find themselves with too few reserves to meet reserve requirements. The lower the discount rate, the cheaper are borrowed reserves and the more banks borrow at the CB’s discount window. Hence, a reduction in the discount rate raises the monetary base and the money supply.

Although these instruments give the CB substantial power to influence the money supply, the CB cannot control money supply perfectly. Bank discretion in conducting business can cause the money supply to change in. ways the CB did not anticipate.

Policy # 4. Fiscal Policy:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Another arm of economic policy is the fiscal policy which is concerned with the policy of taxation, expenditure and borrowing. Fiscal policy as evolved over time has resulted in a tax structure with its great reliance on indirect taxation. As it has failed to contain non-plan expenditures, reinvestible surpluses could not be generated. The government then relied on deficit financing and public borrowing.

All these widened fiscal deficit. However, the situation worsened in the early 1990s when fiscal imbalances rose to an unprecedented height. Necessary fiscal policy measures were made, first in mid-1991. Since then fiscal policy has been aiming at promoting a market-led development of the economy. For instance, a continuous effort is being made even today to simplify both the tax structure and tax laws.

In its new fiscal policy, the Government has taken initiative to strengthen methods of expenditure control. Above all, the new fiscal policy aims at improving allocation of resources in terms of market principles. It aims at giving demand stimulus on the one hand, and restraining supply on the other hand by calibrating tax rates.

One finds a large degree of overlap between these various economic policies and their impact upon the macroeconomic variables. Economic policy measures announced by the Government have been presented in a tabular form so as to form a quick idea about macroeconomic management of the country.

Policy # 5. Indian Agricultural Policy:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Immediately after independence, the country was faced with two major problems: food crisis and shortage of industrial raw materials. The major objectives of the First Plan in the field of agriculture were to correct the imbalances caused by Partition in the supply of food grains and commercial crops and improve infrastructural facilities.

Agriculture, including irrigational power, was, therefore, accorded the highest priority. However, Indian agriculture is characterised by low productivity and backwardness. This demanded agrarian reforms. In fact, there are two ways of improving productivity in agriculture institutional and technological.

At the time of launching of the First Five Year Plan (1951), socialists believed that institutional factors were responsible for low productivity. Another school of thought pointed to the technological backwardness as the prime factor in holding back agricultural production.

Ultimately, institutional measures dominated the government’s agricultural policy up to mid-1960s. In the mid-60s, technological measures were introduced. High priority was accorded to technology as a major input. Focus now shifted to broadening base of agricultural growth and modernisation through infrastructure development: irrigation, drainage, roads, markets and credit institutions, extension of new technology, appropriate price and procurement policies, etc.

However, in the 1990s, the Indian economy introduced structural programmes and new economic policies. In response to these changes, some important policy changes were announced in the agricultural sector. The creation of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has brought a new era for agricultural economies. It has created avenues to export farm products. To exploit such global opportunities, National Agricultural Policy was announced in 2000. The current policy will be described in detail. Before that, we mention briefly the important policy measures introduced in the agricultural sector during 1951-1990.

During the first three Five Year Plans (1950- 65) the institutional reforms and public investment packages were the most dominant policies. Both Central and State governments formulated and enacted various laws relating to land reforms.

(i) Land Reforms:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Land reforms not only contribute to higher productivity but also brings social justice. It entails a redistribution of the rights of ownership and/or use of land away from big cultivators or jotedars and in favour of small cultivators with limited or no landholdings.

The following land reform measures have been taken in India after independence:

(a) abolition of the intermediary system,

(b) tenancy reforms comprising rent regulation, security of tenure and conferment of ownership rights to tenants,

(c) ceiling on landholdings and redistribution of acquired landholdings by the state among the landless workers and small farmers.

The twin objectives of land reform policy were higher agricultural growth rate and social justice so as to abolish exploitation of the tenants.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

During 1950-65, Indian agriculture had been shaped by public investment in agriculture with the objective of achieving self-sufficiency in foodgrains. Such public investment concentrated in the construction of irrigation reservoirs, distribution systems.

(ii) New Agricultural Strategy Encompassing New Technology:

In spite of the land reform measures undertaken in the early decades of planning, the country faced severe food crisis resulting in huge import of foodgrains. Necessity was felt to introduce technological measures to raise agricultural production and productivity in the quickest possible time. During mid-60s to 1990, Government strategy in agriculture evolved around incentive policies for the adoption of modern technology in agriculture coupled with public investment policy.

In the mid- 1960s, the Government of India adopted a new agrarian strategy which goes by different names—seed-fertiliser-water technology, modern agricultural technology, green revolution, etc. It refers to the breeding of high-yielding varieties of wheat and rice and the introduction of modern technologies so as to achieve a sustained breakthrough in agricultural production.

Satisfactory results have been achieved. There has been a considerable increase in production and productivity of major foodcrops. No longer the country is import-dependent; rather, she is now exporting some food crops. Virtual self-sufficiency in foodgrains has been achieved. This achievement relating to productivity of Indian agriculture is described as ‘forest or land-saving agriculture’. Truly speaking without the green revolution it would not have been possible to achieve the state of self- sufficiency in agriculture.

(iii) Institutional Credit:

Indian farmers are too poor to make arrangements for self- financing their agricultural operations. In view of this, they rely greatly on non- institutional private sources of credit which are exploitative in nature. In view of this, the Government of India decided to provide institutional credit to farmers to replace the widely prevalent usurious money-lending.

Barring the creation of cooperative credit societies, commercial banks were nationalised in 1969 with the object of ensuring a smooth flow of credit to agriculturists. Regional rural banks have also been set up to meet the credit needs. An apex credit organisation, called National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), was set up in 1982. In view of the creation of financial institutions, the monopoly position of the village moneylender in the provisioning of agricultural finance has been broken.

(iv) Agricultural Price Policy:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Price policy measures relating to the prices of foodgrains not only aim at increasing production but also aim at acquiring marketable surplus, building up buffer stock of foodgrains to protect the interests of both farmers and consumers. There are two distinct phases of India’s agricultural price policy—one covering the period up to 1965 since independence and other covering the period from 1965 till date. Every season, minimum support prices, procurement prices, etc., are announced in a bid to provide incentive to the farmers to increase production as well as marketable surplus.

(v) Food security—Public Distribution System PDS:

In order to ensure adequate supplies of essential foodgrains and consumer goods such as rice, wheat, edible oils, sugar, kerosene, etc. to consumers, especially weaker sections of the community at cheap and subsidised prices, an elaborate food security system, popularly known as Public Distribution System (PDS) has been built up. This is an essential element of the government’s safety net for the poor. The PDS seeks to control prices, reduce fluctuations in them and achieve an equitable distribution of certain essential consumer goods. It is also an important element of anti-poverty programmes of the government. Thus, the PDS provides food subsidy.

(vi) Input Subsidies:

In addition to food subsidy given to consumers, input subsidies are provided to farmers on a massive scale with the aim of increasing both production and productivity. Subsidies are mostly given to inputs like irrigation, power and fertilisers. Provisioning of such inputs at prices below the market rate not only enables improved use of inputs but also avoids food and raw materials to go up. As a result of input subsidisation and various cross-subsidies of an astronomical height, the state exchequer has become dry. There has now been a strong demand for cut in food subsidies and input subsidies as these have already reached fiscally unattainable level.

(vii) Provisioning of Non-Farm Services:

We have already said about the policy developments in respect of agricultural institutional credit. An important component of agricultural policy is the provisioning of non-farm services like marketing including credit. Agricultural development becomes self-sustaining when additional output can be sold in the market at a remunerative price. Policy measures relating to agricultural marketing may be grouped into (a) setting up of marketing organisation, (b) establishment of regulated markets, (c) provision of storage and warehousing facilities, and (d) crop insurance scheme.

(viii) Trade Policy:

Because of highly state interventionist and discriminating treatment against agricultural trade before 1991, Indian agriculture had little exposure to international trade. Trade liberalisation since 1991, however, bypassed Indian agriculture. But, towards the end of 1990s, trade liberalisation has been faster in tune with the WTO agreements.

In recent years (since 2000), several policy measures have been taken to promote exports of agricultural products. For instance, quantitative restrictions on agricultural trade flow have been dismantled; Export Oriented Units (EOU) in the floriculture sector have been set up; import of capital goods, plant and machinery for establishing food processing units have been made more flexible and liberal, etc.

Policy # 6. National Agricultural Policy:

In view of the problems associated with the agricultural sector during the 1990s, the National Agricultural Policy was announced on July 2000.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Policy Document Aims to Attain Objectives:

i. An annual growth rate of over 4 p.c. in the agricultural sector;

ii. Growth that is based on efficient use of resources and conserves our soil, water and biodiversity;

iii. Growth with equity i.e., growth which is widespread across regions and farmers;

iv. Growth that is demand-driven and caters to domestic markets and maximises benefits from exports of agricultural products;

v. Growth that is sustainable technologically, environmentally and economically.

In order to attain these objectives, the NAP- 2000 envisages measures in the following areas sustainable agriculture; food and nutritional security; generation and transfer of technology; incentives for agriculture; investment in agriculture, institutional structures, and risk management.

In the section on sustainable development, specific measures have been suggested.

The measures are:

(a) to contain biotic pressures on land and to control indiscriminate diversion of agricultural lands for non-agricultural purposes;

(b) to use unutilised wastelands for agriculture and afforestation;

(c) to increase cropping intensity through multiple-cropping and inter-cropping. Agro-forestry and social forestry will receive a major thrust.

Special efforts will be made to increase production and productivity of crops to meet the growing demand for food generated by unabated population pressures and raw materials required for agro-based industries. A major thrust will be put on irrigation, horticulture, floriculture, animal husbandry, fisheries, etc.

The government will emphasise on the generation and dissemination of appropriate technologies in the field of animal production as also health care priority will be given to improve the processing, marketing and transport facilities. Besides this, cooperatives and private sector will be encouraged—more particularly in areas like agricultural research, human resource development, post-harvest management, marketing, etc.

Above all, the NAP-2000 does not ignore the importance of institutional reforms.

Land reform measures now embrace:

(a) consolidation of small and fragmented holdings,

(b) redistribution of ceiling surplus lands,

(c) tenancy reforms,

(d) updating of land records,

(e) development of land-lease markets, and

(f) recognition of women’s rights in land.

This policy envisages National Agriculture Insurance Scheme to provide a package of insurance policy to all farmers and all crops so as to insulate them from natural disasters.

Policy # 7. Industrial Policies:

A. Industrial Policy Resolution of 1948:

In a mixed economy of our sort, the government should declare its industrial policy clearly indicating what should be the sphere of the State and of the private enterprise. A mixed economy means coexistence of the two sectors public and private. This the Government of India did by a policy resolution on 30 April 1948 called the First Industrial Policy Resolution or Industrial Policy Resolution of 1948, which made it clear that India was going to have a mixed economy.

The Industrial Policy Resolution 1948, drawn in the context of our objectives of Democratic Socialism through mixed economic structure, divided the industrial structure into four groups:

(i)Basic and strategic industries such as arms and ammunition, atomic energy, railways, etc. shall be the exclusive monopoly of the State.

(ii) The second group consisted of key industries like coal, iron and steel, ship-building, manufacture of telegraph, telephone, wireless apparatus, mineral oils, etc. In such cases the State took over the exclusive responsibility of all future development and the existing industries were allowed to function for ten years after which the State shall review the situation and explore the necessity of nationalisation.

(iii) In the third group, 18 industries including automobiles, tractors, machine tools, etc. were allowed to be in the private sector subject to government regulation and supervision.

(iv) All other industries were left open to the private sector. However, the State may participate and or intervene if circumstances so demand.

To ensure the supply of capital goods and modern technology, the IPR, 1948 encouraged the free flow of foreign capital. The government ensured that there shall be no discrimination between Indian and foreign undertakings; facilities shall be given for remittance of profit and due compensation shall be paid in case a foreign undertaking is nationalised. The IPR also emphasised the importance of small-scale and cottage industries in the Indian economy.

The Industries (Development and Regulation) Act was passed in 1951 to implement the Industrial Policy Resolution, 1948.

B. Industrial Policy Statement of 1956:

On 30 April 1956, the Government revised its first Industrial Policy (i.e., the policy of 1948), and announced the Industrial Policy of 1956.

The reasons for the revision were:

(i) introduction of the Constitution of India,

(ii) adoption of planned economy, and

(iii) declaration by the Parliament that India was going to have a socialist pattern of society.

All these principles were incorporated in the revised industrial policy as its most avowed objectives.

And the revised policy still provides the basic framework for the government’s policy in regard to industries. The 1956 Policy emphasises, inter alia, the need to expand the public sector, to build up a large and growing cooperative sector and to encourage the separation of ownership and management in private industries and, above all, prevent the rise of private monopolies. “The IPR, 1956, has been known as the Economic Constitution of India” or “The Bible of State Capitalism.”

The Resolution classified industries into three categories having regard to the role which the State would play in each of them:

(i) Schedule A consisting of 17 industries shall be the exclusive responsibility of the State.

Out of these 17 industries, four industries—arms and ammunition, atomic energy, railways, air transport— could be Central Government monopolies; new units in the remaining industries shall be developed by the state Governments.

(ii) Schedule B, consisting of 12 industries, shall be open to both the private and public sectors; however, such industries shall be progressively State-owned.

(iii) All the other industries not included in these two Schedules constitute the third category which is left open to the private sector. However, the State reserves the right to undertake any type of industrial production.

The classification of industries into three categories did not mean that they were being placed in watertight compartments. In appropriate cases, the private sector might be allowed to produce an item falling within Schedule A for meeting its own requirements. Further, heavy industries in the public sector might obtain their requirements from the private sector while the private sector, in turn, would rely on the public sector for many of its requirements.

The IPR, 1956, stressed the importance, of cottage and small scale industries for expanding employment opportunities and for wider decentralisation of economic power and activity. The Resolution also called for all efforts to maintain industrial peace; a fair share of the proceeds of production should be given to the toiling mass in keeping with the avowed objectives of democratic socialism. Regional disparities in industrialisation should be reduced. The government’s attitude to foreign capital would remain unchanged.

The features of the new policy that distinguish it from the previous one are:

(i) Expansion of the role of the State:

This was in keeping with the Mahalanobis Strategy of large-scale industrialisation embodied in the Second Five Year Plan.

(ii) Reduced threat of nationalization:

The apprehensions of nationalisation contained in the previous policy were reduced to the bare minimum.

(iii) More meaningful approach to our concept of a ‘mixed economy:

Various complementaries of the public and private sectors were made clear.

Criticisms:

The 1956 IPR came in for sharp criticisms from the private sector since this Resolution reduced the scope for the expansion of the private sector significantly. Private sector apprehended that the expansion of public sector meant swallowing of the private sector. But this criticism is unfounded. No doubt, public sector had been given an adequate role to play, but, in a mixed economy, public sector must assume the role of a senior partner in the acceleration of economic development. In fact, the Resolution gave ample scope for expansion of the private sector. Even in Schedule A, private sector had been allowed to operate in appropriate cases, though the development of industries mentioned in Schedule A was the exclusive responsibility of the State.

C. Industrial Policy of 1991:

The long-awaited liberalised industrial policy was announced by the Government of India on 24 July 1991. There are several important departures in the latest policy. The New Industrial Policy has scrapped the asset limit for MRTP companies and abolished industrial licensing of all projects, except for 18 (now 5) specific groups. It has raised the limit for foreign equity holdings, thereby demanding a greater participation of foreign capital in the country’s industrial landscape.

The new policy has dismantled all needless, irksome bureaucratic controls on industrial growth. The new policy has re-defined the role of the public sector and has asked the private sector to operate even in those areas which were hitherto reserved for the public sector. Thus, the new policy considers that no longer big and monopoly business houses and foreign capital and multinational corporations (MNCs) are “fearsome” and, in fact, they are benign to the country’s industrial growth.

Anyway, the new policy has decided to take a series of initiatives in respect of the policies relating to the following areas:

(a) industrial licensing,

(b) MRTP Act,

(c) public sector policy,

(d) foreign investment, and

(e) foreign technology agreements.

The highlights of the new policy are:

(i) Industrial licensing will be abolished for all projects except for a short list of industries. The exemption from licensing will apply to all substantial expansion of existing units. The existing and new industrial units will be provided with a broad banding facility to enable them to produce any article so long as no additional investment in plant and machinery is involved.

However, the small-scale industries taking up manufacture of those products reserved for small sector will not be subjected to compulsory licensing procedures. As a result, all existing registration schemes (like de-licensed registration, exempted industries registration, DGTD registration) will be abolished. Now, entrepreneurs are required to fill an information memorandum on new projects and substantial expansion.

(ii) The policy provides for automatic clearance for import of capital goods in cases where the foreign exchange availability is ensured through foreign equity. As for the MRTP Act, the policy states that the pre-entry scrutiny of investment decisions by the so-called MRTP companies will no longer be required.

(iii) The policy intends to scrap the asset limit of the MRTP companies.

(iv) The policy envisages disinvestment of government equity in public sector to mutual funds, financial institutions, general public and workers. For the first time, sick public units will come under the purview of the Board of Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR) for their revival.

A social security mechanism to protect workers’ interests in such affected public sectors has been proposed in this policy. Pre-eminent place of public sector in two core areas production of atomic energy, and rail transport will, however, continue. Reservation for the public sector, as on 2008, is very limited covering only manufacturing involving certain substances relevant for atomic, energy and provision of railway transport.

(v) In order to invite foreign investment in high priority industries, requiring large investments and advanced technology, it has been decided to provide approval for direct foreign investment up to 51 p.c. foreign equity in such industries.

(vi) In a departure from the present locational policy for industries, the policy provides that in locations other than cities of population of more than one million, there will be no requirement for obtaining industrial approvals except for industries subject to compulsory licensing.

Policy # 8. International Trade Policy:

Whether external trade should be allowed to prosper uninterruptedly or be regulated by various means is a matter of great controversy. A country’s position on this issue is commonly known as commercial policy or trade policy. A country’s trade policy, thus, centres around free trade versus protection.

The policy prescription of Ricardo’s comparative cost theory of trade is free trade. By free trade we mean no restrictions on trade. In other words, it refers to the absence of tariffs, quotas, exchange restrictions, taxes and subsidies on production, factor use and consumption.

On the other hand, by protection we mean restricted trade. Free trade eliminates tariff while protective trade imposes tariff or duty. If tariffs, duties and quotas are imposed to restrict the inflow of imports then we have protected trade. This means that government intervenes in trading activities. Intervention in trade by the government is called protection.

In the middle decades of the 19th century, virtually all governments of the world pursued free trade policy. However, Great Britain was the champion of free trade policy at that time. But this tide could not be maintained in the early years of the 20th century. Protectionist tide reached a peak in the depression years of the 1930s.

Virtually free trade policy had been abandoned by all the countries of the world. But, as restrictive trade policy failed to deliver the right amount of goods, industrially advanced nations after the Second World War switched over to free trade policy under the auspices of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

As far as commercial policy was concerned, the entire world became divided into two camps: developed world and developing world. Throughout 1950s and 1960s, developed countries gradually moved towards free trade policy and currency convertibility. International institutions like the IMF, GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) advocated free trade policy.

But developing countries did not oblige these institutions. The prevailing view for the developing countries was of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) which recommended import substituting industrialisation strategy or inward- looking strategy in which goods are produced mainly for the domestic market.

It is to be mentioned here that India followed the import substituting industrialisation (ISI) strategy since the beginning (1951) of the Five Year Plans. As a means of development, substantial protection to domestic industries was granted in India. This was the time when it was believed that “government” or the “state” is better.

Protection or ISI strategy may be seen as one of the manifestations of the government. Protectionist policy received a big jolt in the developing countries in the 1980s when these countries experienced poor economic performance. It was said by the IMF and the World Bank at that time that dramatic economic success could be achieved in developing countries if these countries ‘open up’ or become ‘outward’, instead of being ‘inward’.

Outward looking trade policy emphasises on export-oriented pattern of industrialisation. The basic stimulus for this kind of trade reform came from the experiences of the four high-performing East Asian countries— Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong. This means industries are not to be ‘protected’ by state intervention but to be ‘promoted’ by market mechanism.

India followed a restrictive or protective trade policy up to June 1991 when liberal free trade environment was ushered in. India now moved from ‘inward’ to ‘outward’ looking trade policies. She then gradually removed various kinds of trade restrictions.

Policy # 9. Exchange Rate Management Policy:

Although a nation’s BOP always balances in the accounting sense, it need not balance in an economic sense. An unbalance in the BOP account has the following implications.

In the case of a deficit:

(i) Foreign exchange or foreign currency reserves decline,

(ii) Volume of international debt and its servicing mount up, and

(iii) The exchange rate experiences a downward pressure. It is, therefore, necessary to correct these imbalances.

BOP adjustment measures are grouped into four:

(i) Protectionist measures by imposing customs duties and other restrictions, quotas on imports, etc., aim at restricting the flow of imports,

(ii) Demand management policies—these include restrictionary monetary and fiscal policies to control aggregate demand [C + I + G + (X – M)],

(iii) Supply-side policies—these policies aim at increasing the nation’s output through greater productivity and other efficiency measures, and, finally,

(iv) exchange rate management policies— these policies may involve a fixed exchange rate, or a flexible exchange rate or a managed exchange rate system.

As a method of connecting disequilibrium in a nation’s BOP account, we attach importance here to exchange rate management policy only.

Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rate Management:

An exchange rate is the price at which one currency is converted into or exchanged for another currency. Exchange rate connects the price system of two countries since this (special) price shows he relationship between all domestic prices and ill foreign prices. Any change in the exchange rate between rupee and dollar will cause a change in the prices of all American goods for Indians and the prices of all Indian goods for the Americans. In the process, equilibrium in the BOP accounts will be restored.

Every government has to make international decisions of what type of exchange rate it wants to adopt. This means that government will have to decide how its own currency should be related to other currencies of the world. For instance, it may choose to fix the value of its currency to other currencies of the world so as to adjust its BOP difficulties, or it may choose to allow its currency to move free against other currencies of the world so as to adjust its BOP difficulties. This means that there are two important exchange rate systems—the fixed (or pegged) exchange rate, and the flexible (or fluctuating or floating) exchange rate.

These two exchange rates have been tried and tested in the past. Fixed exchange rate system had been tried by the IMF during 1947-1971 when this system was abandoned. After 1971, the world’s exchange rate became a flexible one or a floating one. Truly speaking, the exchange rate that is being followed by the IMF now is known as the ‘managed floating system’, or the ‘managed flexibility’.

(A) Fixed Exchange Rate:

A fixed exchange rate is an exchange rate that does not fluctuate or that changes within a pre- determined rate at infrequent intervals.

Government or the central monetary authority intervenes in the foreign exchange market so that exchange rates are kept fixed at a stable rate. The rate at which the currency is fixed is called par value. This par value is allowed to move in a narrow range or ‘band’ of ± 1 per cent. If the sum of current and capital account is negative, there occurs an excess supply of domestic currency in the world markets. The government then intervenes using official foreign exchange reserves to purchase domestic currency.

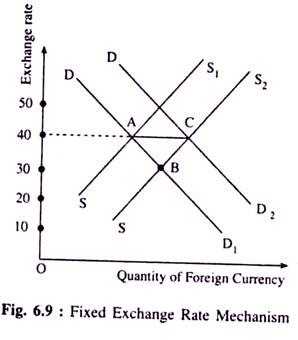

Fixed or the pegged exchange rate can be explained graphically. Let us suppose that India’s demand for US goods rises. This increased demand for imports causes an increase in the supply of domestic currency, rupee, in the exchange market to obtain US dollars. Let DD1 and SS1 be the demand and supply curves of dollar in Fig. 6.9. These two curves intersect at point A and the corresponding exchange rate is Rs. 40 = $1. Consequently, the supply curve shifts to SS2 that cuts the demand curve DD1 at point B.

This means a fall in the exchange rate. To prevent this exchange rate from falling, the Reserve Bank of India will demand more rupees in exchange for US dollars. This will restrict the excess supply of rupee and there will be an upward pressure in exchange rate. Demand curve will now shift to DD2. The end result is the restoration of the old exchange rate at point C.

Thus, it is clear that the maintenance of fixed exchange rate system requires that foreign exchange reserves are sufficiently available. Whenever a country experiences inadequate foreign currency reserves it won’t be able to purchase domestic currency in sufficient quantities. Under the circumstances, the country will devalue its currency. Devaluation refers to an official reduction in the value of one currency in terms of another currency.

(B) Flexible Exchange Rate:

Under the flexible or floating exchange rate, the exchange rate is allowed to vary to international foreign exchange market influences. Thus, government does not intervene. Rather, it is the market forces that determine the exchange rate.

In fact, automatic variations in exchange rates consequent upon a change in market forces are the essence of freely fluctuating exchange rates. A deficit in the BOP account means an excess supply of the domestic currency in the world markets. As price declines, imbalances are removed. In other words, excess supply of domestic currency will automatically cause a fall in the exchange rate and BOP balance will be restored.

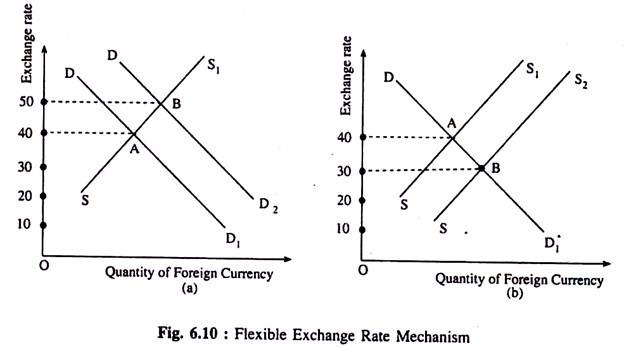

Flexible exchange rate mechanism has been explained in Fig. 6.10 where DD1 and SS1 are the demand and supply curves. When Indians buy US goods, there arises supply of dollar and when US people buy Indian goods, there occurs demand for rupee. Initial exchange rate—Rs. 40 = $1—is determined by the intersection of DD1 and SS1 curves in both the Figs. 6.10(a) and 6.10(b).

An increase in demand for India’s exportable means an increase in the demand for Indian rupee. Consequently, demand curve shifts to DD2 and the new exchange rate rises to Rs. 50 = $1. At this new exchange rate, dollar appreciates while rupee depreciates in value [Fig. 6.10(a)].

Fig. 6.10(b) shows that the initial exchange rate is Rs. 40 = $1. Supply curve shifts to SS2 in response to an increase in demand for the US goods. SS2 curve intersects the demand curve DD1 at point B and exchange rate drops to Rs. 30 = $1. This means that dollar depreciates while Indian rupee appreciates.

(C) Managed Exchange Rate:

Under this heading, floating exchange rates are ‘managed’ partially. That is to say, exchange rates are determined in the main by market forces, but the central bank intervenes to stabilise fluctuations in exchange rates so as to bring ‘orderly’ conditions in the market, or to maintain the desired exchange rate values.

Policy # 10. EXIM Policy:

The Exim Policy (1997-2002):

The export-import policy for five years 1997- 2002 (co-terminus with the Ninth Plan) was announced on March 31, 1997.

Four important objectives of the policy are the following:

1. The primary objective is to make India’s transitions to a globally-oriented vibrant economy faster with a view to deriving the maximum benefits from expanding global opportunities.

2. The second objective is to promote faster economic growth which can be sustained in the long run. This is possible by providing access to essential raw materials, intermediate goods, components and commodity and capital goods required for increasing domestic production.

3. The third objective is to enhance the technological strength and efficiency of Indian agriculture, industry and services with a view to improving their competitiveness in the world market as also for enabling Indian products to attain internationally accepted standards of quality.

4. The fourth and final objective is to provide consumers with quality products at acceptable prices.

The Exim Policy of 1997-2002 was revised on April 13, 1998 and March 31, 1999. In Nov. 1997 India agreed to remove tariff restrictions on 2,714 items over a six-year period. The 1999 review of the Exim policy recognised the importance of exports of services. Moreover those who will be able to export more than 50% of their products will get various facilities.

In short, the trade policy reforms initiated in 1991 have drastically changed the foreign trade situation of the country. It has resulted in the shift from inward-oriented to an outward-oriented policy.

The Exim Policy (2002-07):

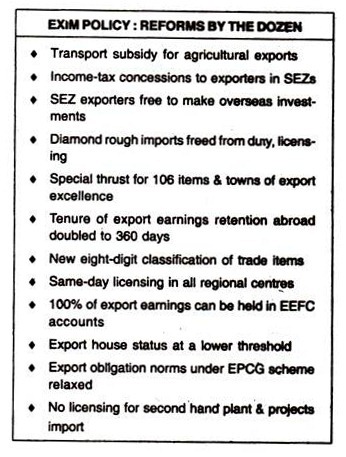

On March 31, 2002 the GOI announced a new five-year Exim Policy- with a view to achieving 1% share of global exports. Quantitative restrictions have been lifted and various incentives offered to agricultural exports and special economic zones to achieve the $ 80 billion annual exports target by 2007.

The policy seems to diversify markets with new export programmes to African and CIS countries and offers benefits to industrial clusters and exports of cottage and handicrafts products, gems and jewellery and electronic hardware sectors, among others.

With a view to achieving 1% share in global exports by 2007, the Government announced lifting of export restrictions, incentives to attract investments in special economic zones, continuation and simplification of existing duty neutralisation schemes, steps to reduce transaction cost and provided sops to boost agriculture, hardware and gems exports.

In the Exim Policy commerce and industry minister Murasoli Maran outlined a major policy thrust for the agriculture sector including removal of packaging restrictions and lifting of quantitative restrictions on all agricultural products except onions and jute.

Though trading in some items would be permitted only though state trading enterprises, the Government would decanalise import of petroleum and petro goods as the administered price mechanism for the sector was being dismantled from April 1, 2002.

As part of the agriculture sector package, Maran announced transport assistance for export of fresh and processed fruits vegetables, paltry, dairy and floriculture products, in addition to wheat and rice products.

The boost electronic hardware exports units in electronic hardware technology parks can freely sell goods covered under the IT Agreement in the domestic market. The units would need to have a positive net foreign exchange as percentage of exports (NEEP) in five years instead of every year and would not face other export obligations.

For gems and jewellery exports, Maran announced waiver of customs duty on import of rough diamonds and abolished the licencing regime on these imports. The Government also provided sops for small scale and cottage industry units as also the handicrafts sector with incentives to access market access initiative (MAI) funds and export house status for units with average export performance of Rs. 5 crores instead of Rs. 15 crores.

“India needs to release itself from feelings of export pessimism and apathy and employ international trade as an engine of growth”, Maran said a year after QRs on imports were lifted.

The minister continued his love for designated areas to promote export excellence and announced sops for industrial cluster-towns which would get funds under MAI for creation of technological services, EPCG benefits and would also be eligible to avail other export schemes with further relaxed norms.

In his last two policies, Maran had announced the establishments of SEZs and Agri Export zones (AEZs). Though no new incentives were announced for AEZs, which now number 20, for SEZs, the minister announced enhanced income tax benefits, central sales tax exemption in case of sale from domestic tariff area to SEZs and removal of restrictions on external commercial borrowings.

He also announced establishment of overseas banking units in SEZs which would be exempted from statutory liquidity ratio and cash reserved ratio to help units and their developers access funds at lower and international rates of interest.

Maran announced the continuation of export incentives schemes including the duty entitlement and passbook (DEPB) scheme, which would now have lower value caps, the advance licence scheme and also provided a relief to export obligation defaulters under the export promotion capital goods schemes.

Under the duty entitlement and passbook, which was expected to be phased out from 2002- 03, the commerce and industry minister also announced a major relaxation for exporters who would now not be subjected to post-market value verifications.

Under the advance licence scheme, the minister announced the withdrawal of annual advance licences, announced in 2001, as the exporters were encountering problems.

The minister said the scope of MAI would be enlarged and increased its allocation three-fold to Rs. 42 crores during 2002-03.

Sops were also offered to status holders including the flexibility to retain 100% foreign exchange earnings under the Export Earners Foreign Currency account and doubling of the normal repatriation period from 180 days to 360 days.

As part of an attempt to usher in a regime with reduced transaction costs, Maran announced a reduction in the maximum fee limit on applications under various schemes, same day licencing in all regional offices of DGFT, reduction in physical examination by the customs department and permission for direct negotiation of export document to help exporters in reducing their bank charges.