The relation between rent and price is commonly misunderstood.

According to the Ricardian theory, rent is a surplus above cost. It does not, therefore enter into price.

We have observed in the preceding discussion that price depends on the cost of production on the marginal land which is no-rent land. In other words, rent is not included in the costs which determine price. It is only when price has risen high enough due to the forces of demand and supply that rent on any plot appears. Thus, rent is the effect or result of price and not the cause of it.

Ricardian View:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ricardo, in his day, tried to explain with the help of this argument that landlords were not to blame for dear corn. “Corn is high not because rent is paid but rent is paid because corn is high.” Rather, even if the landlords sacrificed all their rent (or if it were taken away by a cent per cent tax), corn would still sell at the same price as before. “It has been justly observed”, Ricardo continues, “that no reduction would take place in the price of corn although landlords should forego the whole of their rent”. It means that rent is not a factor that determines price but is itself determined by price.

Here is a weapon for you! Next time a shopkeeper in Connaught Place in New Delhi tells you that he has to charge high prices to meet higher rent charges; you can tell him that he is talking nonsense! If he did not get snobs as customers who did not mind paying him higher prices, he would not go in for that dear shop, and the owner of the building would be compelled to reduce rent.

If the public came to know that he was charging higher prices they would avoid his shop. Only a foolish shopkeeper would put forward this argument or only a foolish customer would be taken in by it. Thus, high rents are paid because much higher prices can be charged rather than prices are high because of high rent.

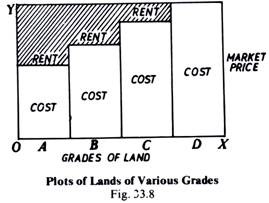

Fig. 33.8 clearly shows that rent does not enter into price. Rectangle D represents the cost of raising produce on ‘D’ class of land. It is seen that cost goes on rising with falling fertility. The market price must cover the cost of production on ‘D’ land, if the produce of D land is needed to meet the total demand.

And when the cost of production on ‘D’ land is being covered by the price, ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ lands are earning a surplus called rent. There is no rent in the rectangle on ‘D’. We can conclude, therefore, that, according to the Ricardian theory, rent is determined by, but does not determine, price. Rent is thus price-determined and not price-determining.

In another sense also, it may be argued that rent does not form a part of price. Land is a free gift of nature. No payment is necessary to maintain the total supply of land. In this sense, rent is not a part of the supply price of land and consequently of the products of land.

Modern View:

Modern economists do not agree with the Ricardian view given above. They point out certain cases in which rent will enter into price. When we think, for example, not of all the land in the country but of the land available for particular uses rent does form an element of price. This is clear from the concept of opportunity cost. Most of the land is capable of being put to several alternative uses. If it is put to one use, it is not available for another use.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The cost of putting land to one use is represented by the loss undergone in not putting it to the next best use. To withdraw it from one use for the sake of another, therefore, some payment has to be made. This is called opportunity cost or transfer price. This payment for the use of land in a particular use enters into price.

From the point of view of an individual firm, all rents of all factors must of course be included in the cost of production, and must, therefore, enter into price. If a farmer is using land belonging to someone else, the rent that he pays is obviously a cost for him. In the case of an owner-cultivator too the rent as a cost is there but its presence is obscured. The payment that he could have received, if he did not cultivate himself, is the opportunity cost of this land.

Further, prices are determined by the scarcity of the products in relation to demand. The rent that an entrepreneur pays is part of his cost of production. If the rent is high, the entrepreneur will tend to hire less land; and conversely, he will use more land, if rent is low. If he uses more land, the supply of land for other purposes is reduced; if he uses less land, the supply available for other purposes is increased. Thus rent, by influencing relative scarcity of land for different uses, affects the prices of different products.

In the last analysis, however, as Davenport points out, rent neither determines price nor is determined by price. Both price and rent are governed by the relative scarcities of the products of land. They both vary with the changes in this relative scarcity. The same principle applies to wages, interest and profits.

Effect of Economic Progress on Rent:

The progress of society can be in different directions. Effects of this progress on rent are, therefore, bound to vary with the directions in which the society progresses. We shall study this effect in its various aspects.

Increase of Population:

An increase in population results in higher rent. Larger numbers need more food. An extra supply of food can be secured only by ploughing less fertile land, because the more fertile or better situated lands are already under the plough.

The only other alternative is more intensive cultivation of superior lands already in use. In either case, this involves greater expenses which farmers will not willingly incur unless they are rewarded by higher prices. Thus more fertile lands will earn higher rents. Hence increase in population increases rent.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Improved Means of Transportation:

Such an improvement may bring about either a fall or an increase in rents. Rents would tend to fall on lands which were already in use and were near the markets. But rents would tend to rise on lands which were fertile but were previously far away from such markets. Thus it was seen that when ocean transport improved between America and Britain, rents fell in Britain, while they rose in America.

Improved Methods of Agricultural Production:

Better methods cause rent to fall as they result in larger production without a parallel increase in demand. Therefore, lands on the margin go out of use, prices tend to fall, and rents come down.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Conclusion:

We may see that, we can trace the effect of economic progress on rent through the change in price. If the price falls, rent falls too, and vice versa. For instance, when population increases, price rises on account of increase in demand and rent rises too.

If improvement in transport brings produce from a cheap place, the price will fall and rent will fall too. On the other hand, if it takes away produce to other markets, the price will rise and the rent will rise. Improved methods of cultivation increase produce and lower price and thus bring down rent.

Rent in a Socialist State:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Even a socialist State cannot do away with the concept of rent. After all, the change from capitalism to socialism will not turn scarce land into an unlimited quantity. Rent as an index of productivity will help in the best allocation of the available land among its various uses. An accounting price-tag will have to be put on the various types of land, the good land being given a higher tag.

In fact, rent as a factor-price is a good device to retain the limited supply of land among the best uses. Even a socialist State will have to direct land from one use to another so as to make its marginal productivity in all uses the same. This marginal productivity will be indicated by rent. This is the only way to ensure a correct allocation of valuable human and non-human resources.