In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Meaning of Balance of Payments 2. Is Balance of Payments Always in Balance? 3. Equilibrium or Disequilibrium.

Meaning of Balance of Payments:

The balance of payments is a summary of all the international transactions of a country and its citizens during a specified period of time. This period is usually of one year, though many countries have now started preparing the quarterly accounts for the purposes of forecasting.

Harvey and Johnson have defined these accounts in these words, “The balance of payments accounts for a country set out, in summary form, all the current and capital transactions which have taken place between the residents of that country and the rest of the world in a given period of time.”

The word ‘residents’ does not only mean the persons, but also business firms, governments, and international agencies located in a particular country. The residents are not necessarily always citizens of the country.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the words of Peterson, “A nation’s international economic balance involves all the international economic transactions that residents of one nation enter into with the residents of all other nations of the world during some specific period of time.” The United States Department of Commerce has defined it as, “the balance of payments of a country consists of the payments made, within a stated period of time between the residents of that country and the residents of the foreign countries.”

According to the IMF, “The Balance of Payments is a statistical statement for a given period showing:

1. Transactions in goods and services and income between an economy and the rest of the world;

2. Changes of ownership and other changes in that country’s monetary gold, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and claims on and liabilities to the rest of the world; and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Unrequired transfers and counterpart entries that are needed to balance, in the accounting sense, any entries for the foregoing transactions and changes which are not mutually offsetting.

It may be defined in a statistical sense as an itemized account of transactions involving receipts from foreigners, on the one hand, and payments to foreigners, on the other. Since the former relate to the international income of a country, they are called ‘credits’, and since the latter have to outgo, they are called ‘debits’.

The balance of payments of a country may be expressed through the following relation:

B = R – P

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Here B denotes the balance of payments; R, total receipts; and P, total payments. Both total receipts and payments can be subdivided into domestic and foreign receipts and payments.

Assuming that domestic receipts and domestic payments are equal, the balance of payments can be stated as:

B = Rf – Pf

If Rf > Pf, there will be a balance of payments surplus. If Rf < Pf, it denotes a deficit in international payments. An equality between receipts and payments (Rf = Pf) signifies equilibrium in international payments.

Is Balance of Payments Always in Balance?

The balance of payments is a statement of international transactions expressed in terms of debits and credits based on double entry system of book-keeping. If all the entries are made correctly, the total debits must be equal to total credits. It happens because each transaction is expressed through entries of equal amounts on the opposite sides of the BOP account.

So if the BOP of a country is considered strictly from the accounting sense, there must be identity between the total credits and total debits and therefore the statement that ‘balance of payments is always in balance’, seems to be true.

In the accounting sense, the BOP remains always in a state of balance. This can be shown on the assumption that an economic system is in a state of equilibrium and the aggregate income (Y) is exactly equal to the aggregate expenditure. Alternatively, it may be assumed that the total injections are exactly equal to total withdrawals in the system.

Total injections include investment (I), government expenditure (G) and exports of goods, services and capital (X). Total withdrawals, on the other hand, include savings (S), taxes (T) and imports of goods, services and capital (M).

I + G + X = S + T + M

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(X – M) = (S -I) + (T – G)

If the budget is balanced so that (T – G) = 0 and the domestic saving and investment are exactly balanced so that (S – I) = 0, it will follow:

(X – M) = 0

In case of purely bilateral trade, all the partial balances with different countries should be in balance. However, if there is multilateral trade, it is not necessary that the regional subtotals in the credit account remain balanced with the regional subtotals in the debit account.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But if it is supposed that the total receipts include not only the value of goods exported but also the value of gold or other monetary reserves exported in order to obtain the purchasing power in excess of that part of imports which is not covered by normal commercial exports, the overall total receipts must remain equal to the total payments. Even when such a situation is recognised, the balance of payments will remain in a state of equilibrium.

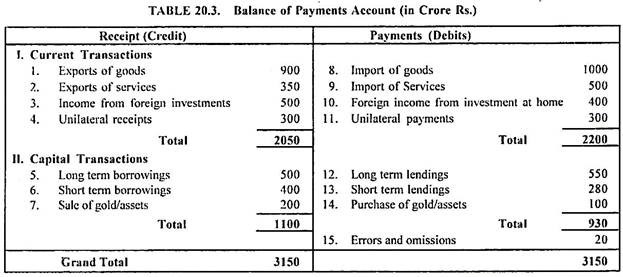

It may be illustrated through a hypothetical account related to the balance of payments of a country as shown in Table 20.3.

In Table 20.3, rows 1 and 8 are related to visible exports and imports. Rows 2 and 9 represent the export and import of services (invisible trade). Rows 3 and 10 refer to investment income. Rows 4 and 11 signify unilateral transfers (such as private and official gifts and donations). Rows 5, 6, 12 and 13 are connected with capital movements. Items 7 and 14 refer to outflow and inflow of gold. The item 15 concerning errors and omissions, in this account, is the balancing item.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The items 1, 2. 3, 4, 8. 9. 10 and 11 are related to the current account. These have the dimensions of flows. The items 5, 6, 7, 12. 13 and 14 are related to the capital account and these have the dimensions of stocks. From the Table 20.3, it follows that the total value of all credits and debits is exactly the same, i.e., Rs. 3150 crores.

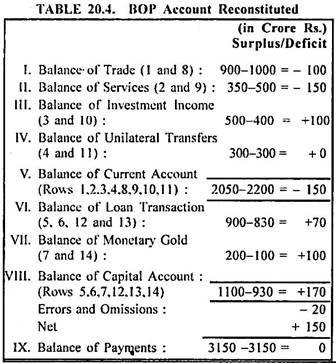

Bo Sodersten has suggested the break-up of the above balance of payments account vertically for the purpose of analysis. The details given in Table 20.3 can be reconstituted as shown in Table 20.4.

Thus in the accounting sense, there is inevitable equality between total credits and total debits (3150-3150 = 0). There is deficit on the balance of current account (- 150). But at the same time there is surplus on the capital account amounting to (+ 170). In the actual balance of payments accounts, the credits and debits may not balance. The balance is, therefore, achieved by including some adjusting or balancing item.

In the above example, the item errors and omission is the balancing item (- 20). From this it may be concluded that the balance of payment always balances in a strict accounting sense. It does not necessarily imply balance of payments equilibrium in the real economic sense.

Equilibrium or Disequilibrium of the Balance of Payments:

The account of international payments must necessarily be in balance; for every credit entry there has to be an off-setting debit entry. Charles P. Kindelberger has defined equilibrium as- “that state of balance of payments over the relevant time period which makes it possible to sustain an open economy without severe unemployment on a continuing basis.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A state of disequilibrium of the balance of payments of a country assumes either the form of a surplus or a deficit. The disequilibrium is said to be favourable when the difference between the autonomous demand for and supply of foreign exchange is positive. On the contrary, a negative difference between the two denotes an unfavourable disequilibrium of payments.

A balance of payments disequilibrium, whether deficit or surplus, has some impact upon the international economic relations and sustained long term balanced growth of international trade. But of the two, the balance of payments deficit is generally considered as a more disturbing phenomenon, since the burden of adjustment tends often to fall more heavily upon the deficit rather than on the surplus countries.

A balance of payments disequilibrium must be attributed to a number of sources according as they have their impact upon the domestic economy.

These sources of balance of payments disequilibrium can be placed broadly in three main categories:

(i) Such sources of disequilibrium which simultaneously cause the worsening of the balance of payments and the lowering of incomes or improving the balance of payments and raising the income levels;

(ii) Such sources which while lowering the income level, tend to improve the balance of payments or while raising the income worsen payments situation; and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) Such sources which have no impact upon the income levels.

In the first category, the disequilibrium is basically caused by the shift in demand from one country’s output to that of another. Such a shift, in addition to its effect upon balance of payments equilibrium, will cause a disturbance in the level of income. The second category covers such sources of payments disequilibria as the differences between the costs and prices in the different countries.

The third category is concerned with such disturbances in the balance of payments which while leaving a country’s current account unaffected bring about changes only in its liquidity position. Such disturbances are caused generally by the desire of domestic or foreign wealth-holders to change the composition of their asset portfolios.

The consideration of the above categories of sources of disturbances is essential for proper understanding of the dimension of the problem and to evolve its appropriate remedy. In this direction, it is worthwhile also to consider whether the balance of payments disequilibrium is temporary or chronic.

A temporary disequilibrium manifests a payments situation in which in-payments, for a short time, exceed the out-payments, followed by a period in which an opposite situation prevails. Such deficits or surpluses are caused by random variations in trade, seasonal fluctuations, and the effects of weather on agricultural output and so on. The deficits or surpluses resulting from such reasons are temporary and are expected to reverse themselves within a fairly short time.

The chronic or fundamental disequilibrium is due to the fundamental changes in the economic position of a country. The main factors that lead to such a situation are the shifts in consumer tastes at home or abroad which affect the country’s imports or exports, technological improvements in products or methods of production in the industries of home country or abroad, differences in the rates of growth of labour force or of capital accumulation between the country and its competitors.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The structural changes in an economic system may also be caused by a major war. The wartime destruction of a country’s productive capacity may hamper the capacity of a country to meet her domestic needs as well as to increase her exports for a considerably long time. The war may also lead to heavy liquidation of foreign investments as a means of obtaining foreign exchange to pay for the imports of war material and also to discharge heavily, mounting international debts.

The foreign policy consideration like heavy outlays for foreign grants and loan and military expenditure also have a very significant bearing upon payments situation. If these expenditures are undertaken and maintained for a considerable length of time, the chronic or fundamental disequilibrium in a country’s balance of payments is likely to result. The chronic deficits that have characterised the U.S. economy during the recent years have been principally on account of these reasons.