Beginners Guide to Balance of Payments!

Read this article to learn about the structure, methods, and problems of internal and external balance of balance of payments.

Introduction:

We are essentially interested here in the monetary aspects of international trade. The main tool of analysis of the monetary aspects of international trade is a statement of the balance of international payments.

The balance of international payments or simply the balance of payments of a country is a systematic record of all international trade, economic and financial transactions of that country during a given period.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, the balance of payments is a statement that records all economic transactions visible and invisible within a given period (usually a year) between the residents’ of one country and the rest of the world (the residents of other countries).

The balance of payments forms part of the national income or social accounts of a country because rest of the world sector is an important sector in social accounting. The transactions in this important ‘rest of the world sector’ are known from the balance of payments of a country.

It shows what is sent to foreign countries by the nations and what is received from them in return. According to Peterson, “A nation’s international economic balance involves all the international economic transactions that residents of one nation enter with the residents of all other nations of the world during some specific period of time” Balance of payments show to the government authorities the international economic position of the country to enable them to reach decisions of monetary and fiscal policies, foreign trade, foreign exchange and international payments.

Balance of payments accounting of a country is done on the basis of double-entry system of recording accounts (credits and debits) with the rest of the world. Each transaction in the balance of payments account gives rise to a receipt (credit) entry and a payment (debit) entry.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

All international transactions that result in payments to a country (say India) are the receipts of that country (India), and they increase India’s stock of or claims on foreign currencies and are recorded as plus or credit entries in India’s balance of payments.

On the other hand, all payments by India (receipts to foreigners) deplete India’s stock of or claims on foreign currencies and may be recorded as minus or debit entries in the balance of payments account of India. Debits must equal credits so that balance of payments are in equilibrium, that is, B = Rƒ – Pj, where, B is balance of payments, Rƒ– receipts from foreigners, and Pf- payments made to foreigners. Clearly, when B is zero (Rƒ – Pƒ= 0), the balance of payments is in equilibrium.

A country with equilibrium balance of payments is often called a country in external balance. When a country’s total receipts (R) from the rest of the world exceed the total payments (P) to the rest of the world, then, balance of payments (B) is said to be favourable. In other words, when B is positive (i.e., when Rƒ – Pƒ > 0 or Rf > Pf), it is called favourable balance of payments. On the other hand, when B is negative (i.e., when Rƒ– Pƒ< 0 or Rƒ < Pƒ), it is called unfavourable or adverse balance of payments. In the former case, when B is positive, a country is called a surplus country; in the latter case, when B is negative, a country is called a deficit country.

Structure of Balance of Payments:

Balance of payments is to be distinguished from balance of trade. Balance of payments or balance of account is a more comprehensive term. It is a wider concept than the balance of trade and includes in its structure the notion of balance of trade.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Balance of trade refers to the difference between the value of imports and exports of commodities or goods or of visible items only. Thus, balance of trade is only a part of the balance of payments which covers the total debits and credits of all items visible as well as invisible.

Invisible items include services like shipping, banking, insurance, interest, gifts, royalties, subsidies, persons to military and civil personnel etc. The balance of trade will be favourable if the value of exports exceeds the value of imports or unfavourable if the value of imports exceeds the value of exports. In both the cases the difference of only visible items is taken into account.

Similarly, a balance of payments may be favourable or unfavourable depending upon whether R is more than P or R is less than P. The balance of accounts consists of two parts—the current account and the capital account. These parts are based on the classification of transaction into real and financial. Real transactions are the actual transfer of goods and services from one nation to the other and, in turn, affect Y, O and E.

These are income creating transactions. Financial transactions are those transactions which involve only the transfer of money or currency (foreign exchange) of claims to money or titles to investment. Financial transactions are often regarded as capital transactions and these do not directly influence the level of income of the countries concerned. The real (or income creating) transactions are entered into the current account part or section of the balance of payments, while financial or capital transactions are entered into the capital account part or section of the balance of payments.

If one wants to know how a country’s foreign trade affects Y, O and E, one has to look to the current account only but when one wants to know about the wealth and debt position of a country, one has to look to capital account.’ The IMF mentions a few items which should be treated as invisible transactions and should be included in the current account of the balance of payments.

These are—travelling expenses on account of business, education, health, pleasure, international conferences—insurance premiums—investment income including interest, rents, dividends, profits, etc.—miscellaneous service items like advertising, commissions, film rentals, pensions, patent fees, royalties, subscriptions to periodicals, membership fees—donations, legacies—repayment of commercial credits—unilateral transfers like gifts, etc. The table on the next page shows a country’s imaginary balance of payments account:

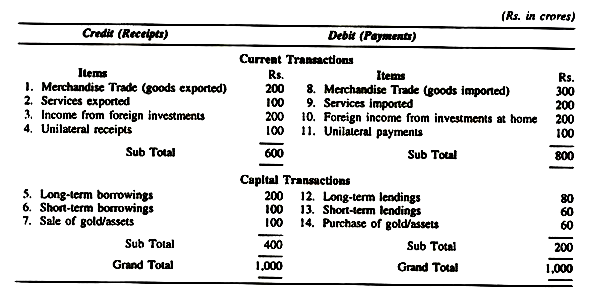

In the table, items 1 and 8 shows the country’s visible exports and imports; items 2 and 9 refer to items of invisible trade ; items 3 and 10 pertain to investment incomes ; items 4 and 11 show unilateral transfers like gifts and donations (private and official). Items 5 and 6, 12 and 13 show capital movements.

Items 7 and 14 show gold outflow and gold inflow. Items 1 to 7 show receipts (R) and items 8 to 14 show payments (P). The total value of both credit and debit side is the same (Rs. 1,000 crore). Moreover, all the items 1 to 4 and 8 to 11 are in current account and represent flow dimension (during the current year). Items 5 to 7 and 12 to 14 represent capital account and show changes in stock magnitudes during the period.

Country’s Balance of Payments-Account:

Balance of trade has no relation with the prosperity or the poverty of the country. Favourable balance of trade is no index of the economic prosperity of a country and the unfavourable balance of trade has nothing to do with the economic backwardness of a country.

For example, India, before the World War II, always had a favourable balance of trade, but was poor and backward whereas, England had always unfavourable balance of trade, but was rich and strong. It is the balance of payments which serves as a better guide to the economic position of a country. Favourable balance of payments is always desirable as it will mean economic prosperity and richness.

Unfavourable balance of payments, on the other hand, shows the weakness of the economy and it may encourage the export of gold. India had unfavourable balance of payments, while England had a favourable one. As a rule the balance of payments should be equal. There may be temporary disequilibrium, but countries cannot afford to have unfavourable balance of payments for long. “Exports must pay for imports”, i.e., both visible and invisible items must be equal. It is not essential that balance of payments, with each and every country, must be equal, but overall balance should be equal and favourable in the long-run.

Methods of Correcting Adverse Balance of Payments:

The balance of payments becomes adverse when the value of imports (visible and invisible) exceeds the value of exports (visible and invisible). One of the basic problems of international economic policy is that of restoring balance, in case there is persistent balance of payments surplus or deficit, since both are bad for normal international economic or trade relations, especially a deficit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There are monetary measures and non-monetary measures which can be adopted to correct an adverse balance of trade. Monetary measures like deflation, depreciation, devaluation, exchange control, etc., not only boost export but also curtail imports. Non-monetary measures like tariffs—import duties, import quotas, export promotion policies and programmes are directly effective.

The different methods by which an adverse balance of payments can be corrected or balanced are:

1. Discouraging Imports and Encouraging Exports:

Efforts should be made to curtail imports by levying duties, tariffs and by fixing import quotas. At the same time, the government may follow policies designed to promote exports such as the reduction of exports duties, use of export bounties and subsidies, quality controls, etc. These measures of checking imports and promoting exports will help in correcting and balancing an adverse balance of payments.

2. Deflation:

In order to bring down the prices in the country, the volume of currency is to be reduced. The central bank, by raising the bank rate, by selling the securities in the open market and by other methods can reduce the volume of credit and demand for imports. This is called the method of deflation—which means contraction of home currency through dear money and credit policy resulting in a fall of domestic costs and prices, giving a stimulus to exports and discouragement to imports. It also restricts home consumption through reduction in incomes. As a result the propensity to import will also decline.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, imports are checked and exports are stimulated and adverse balance is corrected. But deflation is not a very desirable method to correct an adverse balance of payments, because of its adverse effects and tendency to reduce employment. Its efficiency, however, depends on the degree of elasticity of demand for imports and exports of the countries for each other. It is disliked because it reduces money income and increases unemployment.

3. Depreciation:

Depreciation of currency means the decline in the rate of exchange of one currency in terms of another. Imports will become costly as we shall have to pay more, so we import less. Our exports, on the other hand, will become cheap and the demand for exports will increase. Thus, imports will be checked and exports stimulated and balance may become favourable. This method assumes that country has adopted flexible exchange rate policy. Suppose Re. 1 = 30 cents (USA).

If India has an adverse balance of payments with regard to USA, the Indian demand for American currency (dollar, cents) will rise and as such the rupee will depreciate in exchange for American currency. It may change from Re. 1 = 30 cents to Re. 1 = 20 cents. Such a change in the external value of the rupee is called exchange depreciation.

The effects are the same, that is, imports will become costly and discouraged and exports will increase. But if all countries start depreciating their currencies simultaneously, the techniques may not work as it happened during the depreciation war in the 1930s. Moreover, it may result in unfavourable terms of trade besides, causing inflation. Moreover, it does not work under fixed exchange rate.

4. Devaluation:

It means arbitrary lowering of the value of a currency in terms of other currencies. The difference between devaluation and depreciation is that while devaluation is the reduction of the value of a currency by the government, depreciation stands for automatic reduction in the value of currency by market forces. But, both mean the same thing—lower value for the local currency in terms of foreign currencies. The effect is also similar under both depreciation and devaluation. Imports are checked, exports are promoted and a trend towards a favourable balance of payments is created.

A country will resort to this extreme measure of devaluation of its currency to correct a chronic and fundamental disequilibrium in the balance of payments. However, its successful functioning will depend upon certain factors like fairly elastic demand for imports and exports, structure of imports and exports, domestic price stability, international co-operation, co-ordination with other measures, etc. Mere adoption of devaluation measure will not ensure anything till it is properly timed and coordinated.

5. Exchange Control:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It may be defined as government action to regulate exchange rates and to restrict the use of the means of international payment. Under this system of exchange control, which is enforced by the central bank of the country, local currency is not freely convertible into foreign currency. Individuals and firms get license for imports.

Exporters and others surrender foreign exchanges they earn, to the central bank and get in return, local currency. It is a more dependable method to set right a disequilibrium in the balance of payments. Exchange control deals with the deficit only and not its causes. It may prevent a complete breakdown but it cannot eliminate the condition of disequilibrium altogether.

6. Tariff:

The measures consist in checking imports by imposing restriction of various types among which imposition of protective duties is most important. Imposition of high tariff duties would reduce imports to turn the balance of payments in favour of the country.

7. Quota Restrictions:

A country may, instead of or in addition to, imposing heavy duties on goods coming from abroad fix the quantity or ‘quota’ of goods that may be permitted to be imported in a given period. This would automatically limit the imports to the desired level. Thus, imports are restricted, the quotas are fixed, licenses are issued in order to regulate the imports and to correct unfavourable balance of payments.

So many countries adopted the method during the war and in the post-war period. Import quotas are more effective than import duties because they have immediate effect of restricting imports and the marginal propensity to import becomes zero, once the quota limit is reached. Again, the effects of import duties on balance of payments are not certain.

The Problem of Internal and External Balance:

We have seen by now in what sense the balance of payments can be in disequilibrium and in what sense it will always be in equilibrium. We have also studied the interrelationship among exports, imports and national income (foreign trade multiplier). We have also seen how a country can cure a deficit in the balance of payments.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, one of the basic economic problems of many countries is—how to keep the external balance in equilibrium while simultaneously maintaining full employment or internal balance? In other words, the problem is—how can a country achieve, jointly and simultaneously, external and internal balance?

In a general equilibrium model of Walrasian type, where all prices are flexible and where the exchange rate is also flexible—markets will automatically be cleared in such a model and the demand will equal supply. Hence, there will always be full employment and external equilibrium and the two aims are automatically attained as soon as the system reaches its equilibrium position.

From the point of view of international economic policy, such a world is the best of all possible worlds, because economic policy is unnecessary. But in the usual Keynesian model, for instance, full employment does not imply external equilibrium. Here two policy means are necessary to achieve the two aims. Fiscal policy may be used to achieve full employment and commercial policy (exchange rate changes) may be used to achieve external equilibrium.

External and Internal Equilibrium with Flexible Income and Prices:

How to achieve, jointly full employment and equilibrium in the balance of payment (internal and external equilibrium) is the most crucial problem in many countries. An attempt is made to analyze the conditions of external and internal equilibrium with flexible income and prices. We start with a model in which imports are a function of the national income and relative prices.

The level of national income can be changed by the use of a deflationary or inflationary policy (monetary and fiscal policies are both used to manipulate the income level), and the country has a system of fixed exchange rates. The country can, however, use devaluation and revaluation at discrete intervals to correct a deficit in the balance of payments. There are no capital movements for the time being.

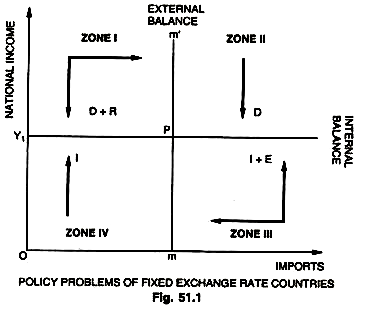

The Figure given below shows the policy problems of a country placed in the situation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

National income is shown vertically and imports are shown horizontally. At a certain level of national income— Yi, there is full employment, that is internal balance. The vertical line mm’ shows the amount of imports (om) needed to produce equilibrium in the balance of payments.

The vertical line mm’ shows the amount of imports that in the short-run gives external balance. The two aims (internal and external balance) of the economy are jointly and simultaneously fulfilled at the point P in the Fig. 51.1 where the two lines intersect. Corresponding to these two aims are the two policy measures—monetary plus fiscal policy, on the one hand, and variations in the exchange rate, on the other.

There are four zones in the diagram. For each zone a specific policy or policy mix has to be applied to achieve the two aims. D denotes deflation, I inflation, E devaluation and R revaluation. In two of the zones only one policy means or measure is needed to attain both the aims (of internal and external balance).

If the economy is at a point in Zone II, there is both over full employment and a deficit in the balance of payments. Under these circumstances, a deflationary policy is needed. In other words, a restrictive monetary and fiscal policy will then alone take care of both external and internal disequilibrium.

Such a policy will exert downward pressure on money incomes and dampen inflation. As national income falls, so do imports, the scope for exports increases and the balance of payments improves. The arrow pointing downward in Zone II shows that deflation is the correct policy for the economy, if the economy is in that zone. On the other hand, in Zone IV, there is both unemployment and a surplus in the balance of payments. Under these circumstances, inflation is the correct policy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An easy monetary policy and an expansionary fiscal policy will lead to an expansion of national income, which, in turn, will lead to an increase in imports (because the country has a surplus in BOP, there is no worry). Hence, inflation alone can lead to the attainment of both the aims in this case.’ The arrow pointing upward in Zone IV shows inflation to be the right policy mainly.

In Zone I a point represents a situation with inflation and a surplus in the balance of payments. To eliminate inflation and over full employment, a deflationary policy is needed, which in turn, will increase the surplus in the BOP. To attain the aim of external equilibrium, a revaluation or appreciation of the exchange rate is essential. This will increase imports and lower exports restoring equilibrium

It may be noted that to get exactly to point P, two policy means might be needed. In zone IV, inflation, no doubt, is the correct policy but it might be possible that country may attain full employment before it attains external equilibrium. Therefore, a combination of the two policy means might, at times, be necessary even in zone II and IV, to get exactly to point P.

in the BOP. But the most difficult situation into which a country can fall is shown in Zone III. Here the country has unemployment and a deficit in the BOP, simultaneously, a situation which a country usually cannot accept with ease for more than a short period of time. To get back to full employment an inflationary policy is needed but it further worsens the deficit in the BOP.

To attain the aim of external equilibrium, devaluation (E) is needed, which may improve the BOP by decreasing imports and increasing exports. The situation in Zone III requires a combination of expenditure increasing policy (to obtain full employment) and an expenditure switching policy (to attain external equilibrium). But an expenditure switching policy, such as devaluation, may not be very successful because here it is combined with an expenditure increasing policy. How, then, can it work? If unemployment is fairly deep and persistent devaluation alone will not bring internal equilibrium, unless combined with inflationary policy.

Timing thus becomes very important. The trick consists in using devaluation as a switching device and to rely on the fact that a larger share of total world demand will be directed towards the country’s exports and as the exports increase, the foreign trade multiplier will work and the national income and employment will expand, at the same time, country’s BOP will improve.

A careful and well timed use of devaluation combined with monetary and fiscal policy should enable the country to attain both internal and external balance. Thus, we have seen how a country can achieve the two aims of full employment and equilibrium in the BOP using monetary and fiscal policy as the main instrument for controlling the level of money income and exchange rate changes as the main instrument for adjusting relative price level. Given the appropriate tools, their judicious use and proper timing, a country should be able to achieve both the aims of internal and external balance jointly and simultaneously.

To emphasize the demand side of a growing economy alone is to lose sight of the capacity— creating aspect of foreign trade which classical theory from Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations down to the present has taught. To stress the supply side alone is to ignore the income-generating aspect of foreign trade when Keynesian theory has shown (and amounts to repeating the classical error of assuming that supply creates its own demand).

Accordingly, the realization that the maintenance of equilibrium growth the full employment (both of labour and capital) but without internal inflation and external imbalance requires that the rate of growth of effective demand and the rate of growth of productive capacity be brought into equality with each other.

If the choice has to be made, however, between domestic growth and balance of payments equilibrium, most underdeveloped countries will perhaps prefer the former to the latter for obvious reasons because internal growth cannot be sacrificed for the sake of external balance.

In developing economies, as an increase in income takes place, the problem of external balance becomes more serious because the propensities to import, save and invest do not remain constant. In such economies, unless the MPS is high, the rise in propensity to import, especially in earlier stages of development, will cause serious balance of payments deficit. But the propensity to import is very high in such economies because the import component of investment is high in poor economies. Moreover, rising incomes mean greater import of consumer goods.

The rich, in whose favour the income is distributed also cause the imports to go up because they have a strong tendency to import luxury goods for conspicuous consumption. The shift of population from rural to urban areas on account of development tends to raise imports of consumption and production goods.

The net effect of planned economic development in poor economies is, therefore, to disturb almost certainly the external balance. “The poor country”, says Meier, “thus confronts a conflict between accelerating its internal development and maintaining external balance.”

This poses a very crucial question whether the cost of economic development should be restricted for the sake of external balance. The problem can be resolved to some extent by determining such a critical rate of maximum investment that can be sustained without causing the balance of payment difficulties. In an open economy, the basic equations of growth given by Harrod’ will have to be rewritten as: GC – S -b and GwCr = S – b where b stands for foreign balance.

A country suffering from a chronic unemployment—Gw > Gn, a positive value of b (i.e., favourable balance of payments) would reduce the deflationary gap. On the other hand, if a country is having inflation, a positive value of b will further accentuate the inflationary potential. Thus, a country with Gw > Gn should try to attain a favourable balance of payments and a country with Gw < Gn should aim at an unfavourable balance.

External and Internal Equilibrium with Capital Movements:

It may, however, be noted that under the international monetary system that prevailed (till 1976), the exchange rates were more or less pegged by the IMF (it was a system of fixed exchange rates popularly called Bretton Woods System).

Under this, a country could alter its rate of exchange by up to 10 per cent without the sanction of the Fund, and any large changes in exchange rates had to be sanctioned by the Fund. Most important devaluations took place in 1949 in Britain, India, West European countries in 1958 it took place in France and again in India in 1966 and in Britain in 1967.

Some economists argue that shifts in the rates of exchange happen infrequently and the implication of devaluation is many—so that it could be ruled out for solving short-term problems. The question that still remains unsolved is that if devaluation can no longer be used effectively to correct a deficit in the balance of payments, some other means will have to be used to cure external disequilibrium.

Some feel that direct controls could be a possible alternative but the trend in trade policy is against them. World economy after World War II saw the emergence of common markets. These markets are based on the principle of free trade among members and a common tariff against non-members. But direct controls and other discriminatory measures can hardly be used to correct external disequilibrium. There is no guarantee that a policy which provides full employment will also lead to external equilibrium. What is the alternative, then?

The answer is to divide the balance of payments into two main parts—the balance of current account and the balance of capital account. Even if there is a deficit in the balance of current account, the country may have an offsetting surplus in the balance of capital account, that is, an inflow of capital.

In other words, a deficit related to the circular flow of income will then be covered by an inflow of capital, that is, there will be a change in stocks (we know that the balance of current account is related to the flow aspect of a country’s economy).

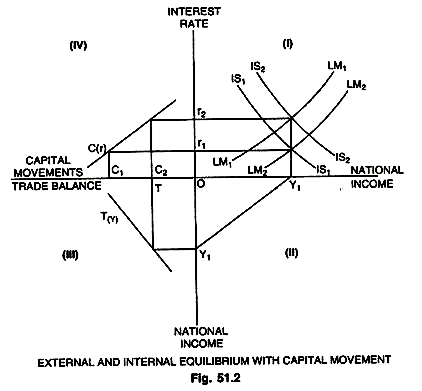

If a deficit in the balance of current account is covered by a surplus in the capital account, it implies that part of the ownership of the country’s capital stock will be transferred abroad. The Fig. 50.2 given here shows how to achieve internal and external balance under fixed exchange rates with capital movements.

The diagram shows the interdependence between the national income and the trade balance and between interest rate and capital imports (it is clear, that a country if it wants to encourage the inflow of capital must have high rates of interest to attract capital). The higher the rate of interest the more encouraging are capital movements toward the country.

Zone I in the Figure shows the famous Hicks- Hansen IS and LM curves of general equilibrium (in a closed economy). Their intersection gives us national income on the one hand and the rate of interest on the other. We relate this relationship with trade balance and capital movements in an open economy to make it more general. In this Figure national income is shown both on the right horizontal axis and on the lower vertical axis. Hence, income is shown by OY1 horizontally as well as vertically (lower part).

Zone III shows the relationship between national income and trade balance OT (shown horizontally on the left side). The trade balance is a function of national income, that is, T(Y). In other words, the higher the income the lower is the trade balance. A surplus in the trade balance will fall if the national income increases. The reason is that an increase in national income in monetary terms gives rise to an increase in imports.

Zone IV shows the relationship between the interest rate and international capital movements. These capital movements are shown horizontally on the left axis and the rate of interest is shown vertically in the upper part.

Capital movements are assumed to be a function of the interest level in the country. The higher the interest, the higher the imports of capital and the lower the interest, the higher are the exports of capital. If the interest rate is Or1, capital movements or exports will amount to OC1. If the rate of interest is higher Or2, capital movements or capital exports will amount to OC2. If the interest level in the country is high enough, the country will instead import capital.

We start from Zone I in which the investment behaviour is shown by IS1 curve and it is intersected by a money supply curve LM2. This gives us national income OY1, which is the full employment income. This income is connected with a trade balance of OT. This gives us an interest rate Or1. At this interest rate, there is an outflow of capital amounting to OC1. Hence, there is a deficit in the balance of payments to the extent of C1T (OC1 – OT).

Under these circumstances, that is given the IS1 curve and the money supply curve LM2 and the interest rate Or1, the economy or the country attains full employment equilibrium. But the capital exports in the situation are larger (OC1) than the surplus in the trade balance (OT)—the country will have a deficit (C1T) in its balance of payments— the country thus attains one of its aims that is, internal equilibrium, but not the other, that is, external equilibrium.

To attain external equilibrium a change in monetary policy is required but this alone may not be enough, because a change in monetary policy will also influence the level of employment. Therefore, an offsetting change in fiscal policy is needed to keep the national income at the full employment level. In other words, a new mix of monetary and fiscal policy will be required to obtain the second objective of external balance, that is, there will be a change in the IS and LM curves.

The supply of money has to be decreased and we shift from LM2 to LM1 curve. This will raise the rate of interest to Or2. This, in turn, will have a depressive effect on national income, and as such the investment will have to be stimulated through fiscal policy. Such encouragement of investment through fiscal policy may take the form of lower taxes and increased government spending.

This will shift the IS curve from IS1 to IS2. The surplus in the trade balance will continue to be equal to OT (because the level of national income continues to be OY1). But at the higher interest rate Or2 capital exports will decrease to OC2. Hence, the deficit has been wiped off and there will also be equilibrium in the balance of payments or external balance is also attained.

The model shows how monetary and fiscal policy together or a mix of both can be used to attain internal and external equilibrium with fixed exchange rates. It also brings to the fore the fact that capital movements are, at times (or become) very important for a smooth functioning of the world economy.

A policy that consciously tries to take advantage of capital movements to attain jointly external and internal equilibrium is very significant and has an important role to play. But such a policy has its own implications and limitations and does not mean that the necessary adjustment in the balance of payments be postponed indefinitely.

The policy mix provides the economy only a breathing time, allowing the economy to develop in such a fashion that equilibrium in the balance of current account will be reached without any immediate adjustment. For example, when a country has a deficit in its trade balance and covers it with capital imports, it depends upon the fact that the country’s price level is out of control, that its wages and prices rise faster than its competitors. If the country continues to cover its deficits with capital imports, the domestic price level will become more and more out of tune as compared to the competing countries.

The interest rate will have to increase more and more in order to attract foreign capital, and finally the country will fall into an unattainable position. The policy mix of the type discussed above can be said to be of limited importance, it implies only a postponement of the necessary adjustment awaiting favourable conditions.

Again, the monetary and fiscal policy mix will be successful if both the monetary authorities who take monetary measures and fiscal authorities who take fiscal measures co-operate closely, or that one authority may handle both policy measures.

If one authority handles one measure (if the central bank controls monetary policy and is responsible for external balance), while the other authority handles the other measure (the government or the Ministry of Finance controls fiscal policy and is responsible for internal balance), it may be impossible to attain both the aims of internal and external balance jointly. In other words, for the policy mix to be successful there must be proper synchronization of both the policies under one authority as far as possible.