In this article we will discuss about the correction in balance of payments through variations in exchange rates.

If a country suffers from payments deficits, the equilibrium adjustments can be possible through the suitable variations in exchange rates. Under the IMF Charter, a member country is permitted to make an adjustment in its exchange parity to deal with a fundamental disequilibrium in its balance of payments. This has led to a great controversy whether the government should have a fixed or a flexible exchange rate.

Milton Friedman has defended the flexible exchange rates when he remarks, “I believe that a system of floating exchange rates would solve the balance of payments problem for the United States far more effectively than our present arrangements. Such a system would use the flexibility and efficiency of the free market to harmonize our small foreign trade sector with both the rest of our massive economy and the rest of the world; it would reduce problems of foreign payments to their proper dimensions and remove them as a major consideration in governmental policy about domestic matters and as a major preoccupation in international policy negotiations, it would foster our national objectives rather than be an obstacle to their attainment.”

Under a system of floating exchange rates, the major gain is the world-wide expansion of foreign trade. It provides every opportunity to the citizens of all countries, and especially those of underdeveloped countries, to sell their products in open markets under equal terms and thereby have every incentive to use their resources efficiently.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The floating and only floating exchange rates, stresses Friedman, can provide a reasonable assurance to all countries that the resultant trade expansion will be balanced and will not interfere with the domestic objectives.

The adherence to a pegged rate of exchange implies that a relatively small foreign sector dominates the national economic policy. Those who regarded this as an advantage refer to it as the discipline of gold standard. With the present pseudo gold standard at work, it is the discipline which we can do well without.

A very frequent objection that is raised against floating exchange rates is that they generate greater speculation and the consequent financial and economic instability. Thus economic instability is traced down to the variations in exchange rates. However, any administrative action to peg the exchange rates creates more complications and only makes the adjustment process more painful.

Even if we accept the truth underlying the argument that the floating rates of exchange introduce an element of uncertainty into foreign trade and thereby discourage its expansion, we cannot afford to ignore the fact that a pegged rate will be under heavy pressure, if the prevailing rate declines, and the authorities will have to meet the situation through internal deflation or some form of exchange control.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this context, remarks Friedman, “The uncertainty about the rate would simply be replaced by uncertainty about internal prices or about the availability of exchange; and the latter uncertainties, being subject to administrative rather than market control, are likely to be more erratic and unpredictable. Moreover, the trader can far more readily and cheaply protect himself against the danger of changes in exchange rates, through hedging operations in a forward market, than he can against the danger of changes in internal prices or exchange availability.” “Floating rates” concludes Friedman, “are therefore, more favourable to private international trade than pegged rates.”

Henery C. Wallich, on the contrary, believes that flexible exchange rates are inadvisable since “their successful function would require more self- discipline and mutual forbearance than countries today are likely to muster.” He points out the possibilities of a worldwide accelerated inflation resulting from the floating exchange rates. He also expresses the fear that such rates will cause increasing international disintegration.

In his words, “International integration and flexible rates are incompatible seems to be the view also of the European Union, who have left no doubt that they want stable rates within the Union. The same applies if we visualize the ‘Kennedy Round’ under the Trade Expansion Act.” Wallich maintains that a system of fixed exchange rates should be allowed to work. But it is highly doubtful if this system is workable in the present state of international economy.

The balance of payments deficits of a country can be better corrected through a system of floating foreign exchange.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Depreciation of a country’s currency—that is, a reduction in its par value in terms of other currencies—will ordinarily improve the country’s balance of trade and payments by reducing foreign exchange payments for imports and increasing the foreign exchange receipts from exports.

If country A permits the par value of her currency in terms of the currency of country B to depreciate, she becomes a better market for the residents of country B to purchase their requirements from. This will bring in larger receipts of foreign exchange for country A. The country B, on the other hand, becomes a costly market for the residents of country A to purchase from.

As a result, there is a decline in the payments to country B. The extent to which balance of payments deficit will respond to a given change in the rate of exchange depends upon the relation between the price-elasticities of demand for imports and exports and the elasticities of demand and supply for the currency of A.

If, for instance, the Indians have an elastic demand for British goods, a fall in the rupee price of British goods will make them spend more. If, on the other hand, the Indians have an inelastic demand for British goods, a fall in the rupee price of these goods will cause the Indians to spend less on British goods, while a rise in prices will make them to spend more.

The price elasticities of domestic demand for imports and of the foreign demand for exports exercise a substantial impact upon the balance of payments position of a country. The greater the price elasticities of these demands, the greater will be the effect of a given change in the exchange rate on the balance of payments position and vice- versa.

It will mean that given the greater price elasticities of these demands a smaller change in the foreign exchange rate, will be required to remove the balance of payments disequilibrium and vice-versa.

The usual effect of a given rise in exchange rate is to effect a reduction in the autonomous international payments and an expansion in autonomous receipts. This results in a fall in demand for and a rise in the supply of foreign currency. The reverse effects will flow from a fall in the foreign exchange rate.

It may be maintained here that a rise in exchange rate means exchange depreciation since it involves a depreciation in the international value of the currency unit in terms of other national currencies. A fall in exchange rate, on the contrary, is referred as the exchange appreciation or revaluation, since it involves an increase in the international value of the domestic currency.

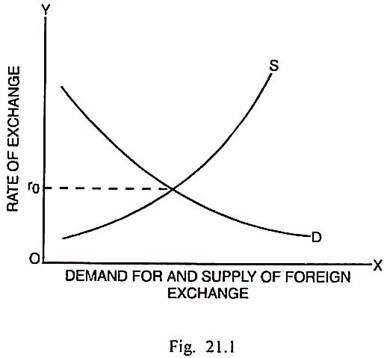

Assuming perfectly competitive conditions in the foreign exchange market, the rate of exchange is determined by the forces of demand and supply. Suppose that there are just two countries A and B and each country, in return of her exports, demands the currency of the other. The demand for the currency of country A arises simply because the people of country B wish to purchase goods from country A.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The demand curve for the currency of country A will tend to slope downwards because in that case a fewer units of currency of B have to be given up per unit of currency of country A. It will thus become cheaper to buy goods from country A. The supply curve of the currency of country A, on the opposite, will slope upwards as more units of currency of country B can be obtained per unit of currency of country A, and it becomes cheaper to buy goods from country B.

Given the demand and supply functions related to foreign exchange, the equilibrium rate of exchange is determined by the intersection between the demand and supply curves.

Fig. 21.1 shows r0 as the equilibrium rate of exchange between the currencies of the two countries. A rise in the exchange rate will reduce the quantity of foreign exchange demanded and will increase the quantity supplied and vice-versa. A fall in the rate of exchange, on the contrary, will have the opposite effects.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

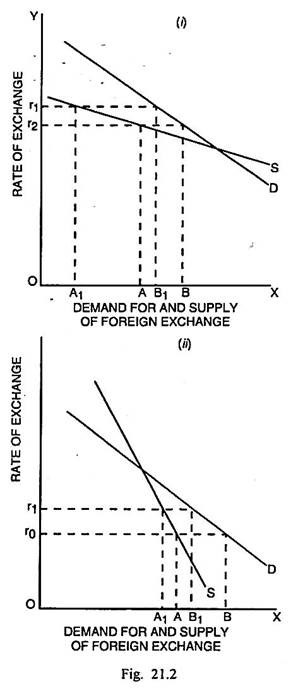

While the demand curve for foreign exchange will almost invariably slope negatively, there is more uncertainty about the effect of depreciation on the supply for foreign exchange derived from the depreciating country’s export. While the depreciating country will sell a larger quantity of goods as a result of depreciation, it may possibly receive less foreign exchange.

If the demands for various categories of goods and services exported by the depreciating country are typically inelastic, exchange depreciation may reduce the export proceeds. The supply curve in such a situation will be negatively sloping. We can visualise two possible cases of negatively sloping curves of foreign exchange and trace their effects upon the balance of payments.

Fig. 21.2 (i) depicts that the payments deficit at the exchange rate r2 is AB. A depreciation in the exchange rate from r2 to r1 results in the reduction in export proceeds by AA1 and reduces the payments for imports by BB1.

Since there is a greater decline in export proceeds than the reduction effected in payments for imports, the depreciation in exchange rate will increase the payments deficit rather than reducing it. In this case the payments deficit increases from AB to A1B1 and necessary correction in the situation can be made through the appreciation of exchange rate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Fig. 21.2 (ii), both demand and supply curves slope negatively but the latter is more steeply sloped than the former. At an exchange rate r0, the payments deficit is AB. A depreciation in the exchange rate from r0 to r1 results in a decline in export proceeds by AA1. The payments for imports, on the other hand, decline by BB1. Thus, an exchange depreciation brings about an improvement in the payments deficit. The overall deficit, in this case, is reduced from AB to A1B1.

In Fig. 21.2 (i), the balance of payments equilibrium will be achieved when the rate of exchange is appreciated to an extent that the point of intersection between the demand and supply curves is reached. In Fig. (ii), on the opposite, the payments deficit will be fully eliminated, when the exchange rate is depreciated by an amount such that the point of intersection between the demand and supply curves is reached.

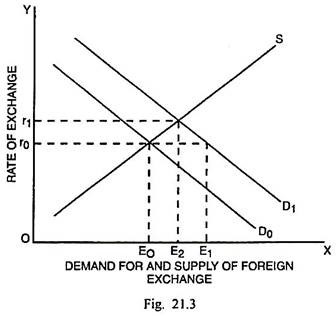

Now we shall briefly study how the changes in the exchange rate can maintain balance of payments equilibrium after the equilibrium is disturbed either due to the autonomous capital outflow or the increased preference for the foreign products. The process of adjustment has been shown through Fig. 21.3.

Given the demand curve D0 and the supply curve S, the equilibrium rate of exchange is determined at r0. The equilibrium position may be disturbed either by the capital outflow or increased preferences for foreign products such that the demand curve for foreign exchange shifts from D0 to D1 and the payments deficit equivalent to E0E1 emerges.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The equilibrium in payments is restored through the depreciation of exchange rate from to r1. This simple model proves that the problem of balance of payments surplus or deficit does not arise, if the foreign exchange rates are allowed to fluctuate freely. This raises the question- why then, do most of the countries intervene in the foreign exchange market?

Harvey and Johnson believe that they do so for the following main reasons:

(a) To off-set temporary autonomous capital movements;

(b) To eliminate the effects of speculation in foreign exchange;

(c) To stabilise the exchange rates; and

(d) To prevent frequent fluctuations in exchange rate.