All disequilibria are mainly divided into two categories, namely price disequilibria and income disequilibria.

The income disequilibria are of two types, namely, cyclical and secular disequilibria.

The price disequilibria are of two categories, namely, structural disequilibria at the goods level and the structural disequilibria at the factor level.

1. The Cyclical Disequilibrium:

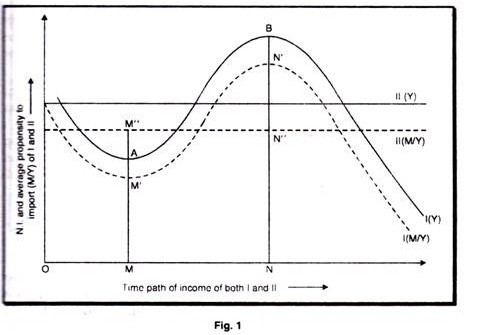

Cyclical disequilibrium occurs either because the patterns of business cycles in different countries follow different paths or because income elasticities of demand for imports in different countries are different. We may illustrate this by some diagrams for two countries. In fig. 1, national money income is stable in country II and fluctuates cyclically in country I. The income elasticity of demand for imports may or may not be the same. In the diagram Y represents national income and M/Y represents average propensity to import.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the diagram, national income is stable in country II and fluctuates cyclically in country I. Import is a function of income. The income elasticity of demand for imports in country II is not involved, since income is stable. Country I is witnessing ups and downs in its national income and imports.

In this situation is imports (and II’s exports) will decline during depression and rise in prosperity. Country II’s imports (and I’s exports) will continue steadily. The result is that country I will have an export surplus during depression and import surplus during prosperity. Let us take two points in the income path of Country I. In Figure 1, A and B provide two contrasting points. At the point A, MMI is country’s import; corresponding to its income AM In depression. The country’s export at this point is MMII corresponding to Income at A.

Thus, there appears an export surplus in country I’s BOP. During the depression, a country is bound to have an export surplus due to both price effect and income effect. Point B is the point of inflation. At B, country I’s import is NNI and export is NNII. During inflation, a country is bound to have an import surplus due to both price and income effect. Import being a function of national income, when the income increases, the import rises, thus creating the BOP disequilibrium. In this case, the income paths of the two countries are different and the income elasticities of demand for imports are also different. The import of country I is income elastic and the import of country II is stable.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

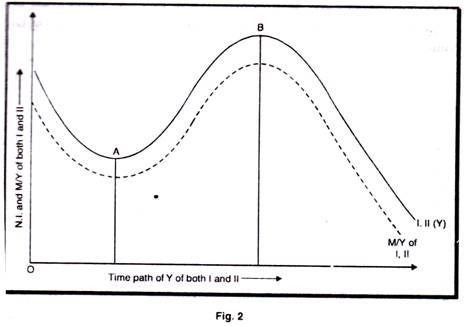

If we assume that the income paths of two countries are identical and the income elasticities of imports of two countries are also identical, then there would be no BOP disequilibrium. This is illustrated in figure 2. Exports and imports rise and fall with national income, but by the same amount. Cycles are a necessary condition of pure cyclical disequilibrium, but not a sufficient one.

The cyclical fluctuations in income may be induced by the exogenous or by endogenous factors. Thus, two types of income variation need to be distinguished: those that occur independently in one or more countries and those that are linked together through the international propagation of business cycle. The International Monetary Fund was created during the war to assist in financing cyclical deficits.

Cyclical disequilibrium is caused by short-term cyclical fluctuation in income. The disequilibrium may be caused by countries following different cyclical patterns of income, or the same income pattern with different income elasticities or identical income patterns and income elasticities but different price elasticities.

2. Secular Disequilibrium:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The word “secular” refers to long periods of time in which change takes place slowly. Secular disturbances to equilibrium are those which occur because of long-run and deep seated changes in an economy as it moves from one stage of growth to another. The current account tends to follow a varying pattern from one period of growth to another. In the early stage of development, domestic investment tends to exceed domestic savings and imports to exceed exports. Disequilibrium, under these circumstances, may arise because insufficient capital is available to finance the import surplus.

At a further stage of development that of the young creditor domestic savings tend to exceed domestic opportunities for investment, and exports outrun imports. Disequilibrium may result because the long term capital outflow falls short of the surplus savings or because surplus savings exceed the amount of investment opportunities abroad.

At a still later stage, when savings are equal to domestic Investment and long-term capital movements are, on balance zero, it may be considered a sign of disequilibrium to permit any change at all. The balanced stage, is called that of the adult creditor. To move to the stage of the mature creditor, which consumes capital because consumption and investment outturn production, is perhaps a sign of disequilibrium by itself, even if the resultant import surplus can be readily financed.

Leaving aside this least possible exception, however, we can summarize by saying that, in secular equilibrium, the movement of long-term capital and the deep seated factors affecting the equilibrium positions of savings and investment are adjusted to each other.

Secular disturbance to this equilibrium occurs when both the long- term capital movement gets out of adjustment with the deep-seated factor affecting savings and Investment or scheduled savings and Investment change without an offsetting change in the movement of long-term capital. A developing economy is bound to witness secular disequilibrium in its BOP in the early stages of its economic development.

Secular disequilibrium occurs when the rate of foreign lending falls short of the excess of intended savings over intended investment or the rate of foreign borrowing falls short of the excess of intended Investment over intended savings.

The remedies evidently lie in changing the relationship between savings and investment, by monetary and fiscal action, or in changing the rate of foreign lending only in the limiting case where technological progresses at a faster rate in one country than in another takes the form of more rapid reductions in prices would exchange depreciation be appropriate. Exchange depreciation occurs as a result of secular imbalance, and recently import restrictions have been used. A fair case can be made for multiple exchange practices in the absence of retaliation.

3. Structural Disequilibrium at the Goods Level:

Structural disequilibrium at the goods level occurs when a change in demand or supply of exports or imports alters a previously existing equilibrium or when a change occurs in the basic circumstances under which income is earned or spent abroad, in both cases without the requisite parallel changes elsewhere in the economy.

The simplest illustration is furnished by a change in demand. Suppose, there is a decline in the world demand for Swiss embroidery due to a change in taste. The resources previously engaged in embroidery production must shift into other lines of activity or adjust their expenditures downward.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So far as the country as a whole is concerned, the displaced resources or some others must shift into another export line, or the country must restrict imports. If the called for changes fail to take place or occur in inadequate degree, the country will experience a structural disequilibrium.

Structural disequilibrium may be caused by a change in taste or technology or in anything which alters the price of an export upward or downward. An increase in the foreign demand for a country’s output is structural disequilibrium of a sort, but one with which it is not difficult to deal. The remedy is an increase in output of the product and an increase in consumption and imports by the country.

The cause of disturbance may be a change in supply. The classic example was crop failure, which cut off the supply of a country’s exports and produced a shortfall of exports below imports. A bumper crop abroad which lowered world prices would have much the same effect.

The domestic demand and the foreign supply of imports can change adversely to cause a structural disequilibrium as well as the domestic supply and the foreign demand for exports.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A deficit arising from a structural change can be filled by increased production or decreased expenditure, which have their reflection in international transactions in increased exports or decreased imports.

In the pure case of structural disequilibrium the remedy is not shift of resources or reduction in expenditure but shift of resources and reduction in expenditure. How large a reduction in expenditure will be required will depend upon the nature and extent of the disequilibrium and upon the elasticities of the demand and supply in the alternative lines of endeavor.

According to Ellsworth, “Any of these change in demand and supply conditions, whether they originate at home or abroad, affect a country’s economic structure in relation to that of the rest of the world and therewith its balance of payments”.

According to Kindleberger, “Thus structural disequilibrium is a maladjustment of the relative price system. At the goods level it is a misallocation of resources relative to prices, generally arising from a change in demand and supply of internationally traded goods.”

4. Structural Disequilibrium at the Factor Level:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Structural disequilibrium at the factor level results from factor prices which fail to reflect accurately factor endowments. Thus, structural disequilibrium is typified by an inappropriate relation between factor prices and their relative supplies.

The disequilibrium may not appear directly in the BOP. The economy may, for example, adjust to the factor prices as they are choosing the production functions, lines of comparative advantage and disadvantage, or exports and imports, level of income and exchange rate so that the BOP is in equilibrium at those factor prices. The result, however, will be that one or more factors have structural unemployment. Typically, the price of labour is too high and that of capital too low.

The reasons for this may lie in the collective bargaining strength of labour. If the price of labour is too high the country will choose lines of comparative advantage in which labour is used more sparingly than it should be and import goods with a higher labour content than is appropriate. The country’s comparative advantage in labour intensive goods and services will be understated and its comparative disadvantage in these lines will be overstated. Balance in BOP may still be possible, but only at the cost of unemployed labour. If an attempt is made to employ this labour it will have to be done at factor proportions which differ from those utilized throughout the economy.

According to Kindleberger “In a broad sense, the balance of payments is in disequilibrium when factor prices, out of line with factor endowments, distort the structure of production from the allocation o. resources which appropriate factor price would have indicated.’