The following points highlight the seven main objectives of a business firm. The objectives are: 1. Profit Maximisation 2. Multiple Objectives 3. Marris Growth Maximisation 4. Baumol’s Sales Maximisation 5. Output Maximisation 6. Security Profits 7. Satisfaction Maximisation.

Business Firm: Objective # 1.

Profit Maximisation:

In the conventional theory of the firm, the principal objective of a business firm is profit maximisation. Under the assumptions of given tastes and technology, price and output of a given product under perfect competition are determined with the sole objective of maximising profits. The firm is supposed to act as one of a large number of producers which cannot influence the market price of the product.

It is the price-taker and quantity-adjuster. Thus the demand and cost conditions for the product of the firm are determined by factors external to the firm. In this theory, maximum profits refer to pure profits which are a surplus above the average cost of production. It is the amount left with the entrepreneur after he has made payments to all factors of production, including his wages of management.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, it is a residual income over and above his normal profits. It is a necessary payment for an entrepreneur to stay in the business. The rules for profit maximisation are (1) MC = MR and (2) MC should cut MR from below.

Business Firm: Objective # 2.

Multiple Objectives:

The basis of the difference between the objectives of the neo-classical firm and the modern corporation arises from the fact that the profit maximisation objective relates to the entrepreneurial behaviour while modem corporations are motivated by different objectives because of the separate roles of shareholders and managers. In the latter, shareholders have practically no influence over the actions of the managers.

As early as in 1932, Berle and Means suggested that managers have different goals from shareholders. They are not interested in profit maximisation. They manage firms in their own interest rather than in the interests of shareholders. Shareholders cannot have much influence on managers because they do not possess adequate information about companies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The majority of shareholders cannot attend annual general meetings of companies and thus give their proxies to the directors. Thus modem firms are motivated by objectives relating to sales maximisation, output maximisation, utility maximisation, satisfaction maximisation and growth maximisation which we explain briefly.

a. Simon’s Satisficing Objective:

Nobel laureate, Herbert Simon was the first economist to propound the behavioural theory of the firm. According to him, the firm’s principal objective is not maximising profits but satisficing or satisfactory profits.

In Simon’s words:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

“We must expect the firms goals to be not maximising profits but attaining a certain level or rate of profit holding a certain share of the market or a certain level of sales.” Under conditions of uncertainty, a firm cannot know whether profits are being maximised or not.

In analysing the behaviour of the firm, Simon compares the organisational behaviour with individual behaviour. According to him, a firm, like an individual, has its aspiration level in keeping with its needs, drives and achievement of goals.

The firm aspires to achieve a certain minimum or ‘target’ level of profits. Its aspiration level is based on its different goals such as production, price, sales, profits, etc., and on its past experience. This also takes into account uncertainties in the future. The aspiration level defines the boundary between satisfactory and unsatisfactory outcomes.

In this context, the firm may face three alternative situations:

(a) The actual achievement is less than the aspiration level;

(b) The actual achievement is greater than the aspiration level; and

(c) The actual achievement equals the aspiration level.

In the first situation, when the actual achievement lags behind the aspiration level, it may be due to wide fluctuations in economic activity or on account of qualitative deterioration in the performance level of the firm.

In the second situation, when the actual achievement is greater than the aspiration level, the firm is satisfied with its commendable performance. The firm is also satisfied in the third situation when its actual performance matches its aspiration level. But the firm does not feel satisfied in the first situation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It may be that the firm has set its aspiration level very high. It will, therefore, revise it downward and start a search activity to fulfil its various goals in order to achieve the aspiration level in the future. Similarly, if the firm finds that the aspiration level can be achieved, it will be revised upward. It is through such search activity that the firm will be able to reach the aspiration level set by the decision-maker.

The search process may be done through sequence of possible alternatives using past experience and rules-of-thumb as guidelines. But the search activity is not a costless affair. “The advantage of search activity must be balanced against its cost, and once search has revealed that what appears to be a satisfactory course of action, it will be abandoned for the time being. In this way, the firm’s aspiration level is periodically adapted to circumstances and the firm’s reaction to them. The firm is not maximising, since, partly on account of the cost, it limits its searching activities. The firm, while behaving rationally, is ‘satisficing’ rather than maximising.”

Criticism:

This theory has certain weaknesses.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. The main weakness of the satisficing theory of Simon is that he has not specified the ‘target’ level of profits which a firm aspires to reach. Unless that is known it is not possible to point out the precise areas of conflict between the objectives of profit maximising and satisficing.

2. Baumol and Quant do not agree with Simon’s notion of ‘satisficing’. According to them, it is “constrained maximisation with only constraints and no maximisation.”

Despite these weaknesses, Simon’s model was the first model on which the later behavioural models have been developed.

b. Behavioural theory of organisational goals:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Cyert and March have put forth a systematic behavioural theory of the firm. In a modern large multiproduct firm, ownership is separate from management. Here the firm is not considered as a single entity with a single goal of profit maximisation by the entrepreneur.

Instead, Cyert and March regard the modem business firm as a group of individuals who are engaged in the decision-making process relating to its internal structure having multiple goals. They emphasise that the modern business firm is so complex that individuals within it have limited information and imperfect foresight with respect to both internal and external developments.

Organisational goals:

Cyert and March regard the modern business firm as a complex organisation in which the decision-making process should be analysed in variables that affect organisational goals, expectations and choices. They look at the firm as an organisational coalition of managers, workers, shareholders, suppliers, customers, and so on.

Looked at it from this angle, the firm can be supposed to have five different goals: production, inventory, sales, and market share and profit goals.

Implications of the Cyert-March Model for Price Behaviour:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

They illustrate the key processes at work in an oligopolistic firm when it makes its decisions on price, output, costs, profits, etc. In this theory, each firm is assumed to have three sets of goals for profits, production and sales, and three basic decisions to make on price, output and sales effort in each time period.

It takes into consideration the firm’s environment at the beginning of each period which reflects its past experience. Its aspiration levels are modified in the light of this experience. The organisational slack is the difference between total available resources and total necessary payments to members of the coalition.

Price is sensitive to factors influencing increases and decreases in the amount of organisational slack, to feasible reductions in expenditure on sales promotion and to changes in profit goals.

Each firm is assumed to estimate its demand and production costs and choose its output level. If this output level does not yield the aspired level of profits, it searches for ways to reduce costs, re-estimate demand and, if required, to lower its profit goal.

If the firm is prepared to lower its profit goal, it will readily reduce its price. Thus price is found to be sensitive to factors affecting costs due to the close relationship between prices, costs and profits.

Criticism:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Cyert and March theory of the firm has been severely criticised on the following grounds:

1. Economists have questioned: ‘Whether it is a theory at all? It deals with particular cases whereas a theory is expected to be a general approximation of the behaviour of firms. Its empirical base is too limited to provide the details of theorising. Hence it fails as a theory of the firm.

2. The behavioural theory relates to a duopoly firm and fails as the theory of market structures.

3. The theory does not consider either the conditions of entry or the effects on the behaviour of existing firms of a threat of potential entry by firms.

4. The behavioural theory explains the short-run behaviour of firms and ignores their long-run behaviour.

Conclusion:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Despite these criticisms, the behavioural theory of Cyert and March is an important contribution to the theory of the firm which brings into focus multiple, changing and acceptable goals in managerial decision-making.

c. Williamson’s Utility Maximisation:

Williamson has developed managerial utility-maximisation objective as against profit maximisation. It is one of the managerial theories and is also known as the ‘managerial discretion theory’. In large modem firms, shareholders and managers are two separate groups. The former want maximum return on their investment and hence the maximisation of profits.

The managers, on the other hand, have consideration other than profit maximisation in their utility functions. Thus the managers are interested not only in their own emoluments but also in the size of their staff and expenditure on them.

Thus Williamson’s theory is related to the maximisation of the manager’s utility which is a function of the expenditure on staff and emoluments and discretionary funds. “To the extent that pressure from the capital market and competition in the product market is imperfect, the manager, therefore, has discretion to pursue goals other than profits.”

The managers derive utility from a wide range of variables. For this Williamson introduces the concept of expense preferences. It means “that managers get satisfaction from using some of the firm’s potential profits for unnecessary spending on items from which they personally benefit.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To pursue his goal of utility maximisation, the manager directs the firm’s resources in three ways:

1. The manager desires to expand his staff and to increase his salaries. “More staff is valued because they lead to the manager getting more salary, more prestige and more security.” Such staff expenditures by the manager are denoted by S.

2. To maximise his utility, the manager indulges in ‘featherbedding’ such as pretty secretaries, company cars, too many company phones, ‘perks’ for employees, etc. Such expenditures are characterised as ‘management slack’ (M) by Williamson.

3. The manager likes to set up ‘discretionary funds’ for making investments to advance or promote company projects that are close to his heart. Discretionary profits or investments (D) are what remain with the manager after paying taxes and dividends to shareholders in order to retain an effective control of the firm.

Thus the manager’s utility function is

U = f (S, M. D).

Where U is the utility function, S is the staff expenditure, M is the management slack and D is the discretionary investments. These decision variables (S, M, and D) yield positive utility and the firm will always choose their values subject to the constraints, S 3 О, M 3 О and D 3 O. Williamson assumes that the law of diminishing marginal utility applies so that when additions are made to each of S, M and D, they yield smaller increments of utility to the manager.

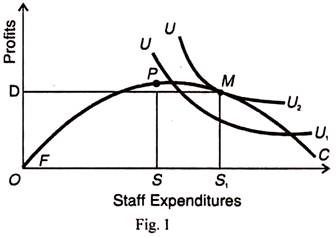

To explain Williamson’s utility maximisation theory diagrammatically, it is assumed for the sake of simplicity that

U = f(S, D)

So that discretionary profits (D) are measured along the vertical axis and staff expenditures (S) on the horizontal axis in Figure 1. FC is the feasibility curve showing the combinations of D and S available to the manager. It is also known as the profit-staff curve. UU1 and UU2 are the indifference curves of the manager which show the combinations of D and S.

To begin, as we move along the profit-staff curve from point F upward, both profits and staff expenditures increase till point P is reached.

P is the profit maximisation point for the firm where SP is the maximum profit levels when OS staff expenditures are incurred. But the equilibrium of the firm takes place when the manager chooses the tangency point M where his highest possible utility function UU2 and the feasibility curve FC touch each other. Here the manager’s utility is maximised.

The discretionary profits OD (=S1M) are less than the profit maximisation profits SP. But the staff emoluments OS1 are maximised. However, Williamson points out that factors like taxes, changes in business conditions, etc. by affecting the feasibility curve can shift the optimum tangency point, like M in Figure 1. Similarly, factors like changes in staff, emoluments, profits of stockholders, etc. by changing the shape of the utility function will shift the optimum position.

Criticism:

But there are some conceptual weaknesses of this model.

1. He does not clarify the basis of the derivation of his feasibility curve. In particular, he fails to indicate the constraint in the profit-staff relation, as shown by the shape of the feasibility curve.

2. He lumps together staff and manager’s emoluments in the utility curve. This mixing up of non-pecuniary and pecuniary benefits of the manager makes the utility function ambiguous.

3. This model does not deal with oligopolistic interdependence and of oligopolistic rivalry.

Business Firm: Objective # 3.

Marris Growth Maximisation:

Robin Marris in his book The Economic Theory of ‘Managerial’ Capitalism (1964) has developed a dynamic balanced growth maximising theory of the firm. He concentrates on the proposition that modern big firms are managed by managers and the shareholders are the owners who decide about the management of the firms.

The managers aim at the maximisation of the growth rate of the firm and the shareholders aim at the maximisation of their dividends and share prices. To establish a link between such a growth rate and the share prices of the firm, Marris develops a balanced growth model in which the manager chooses a constant growth rate at which the firm’s sales, profits, assets, etc., grow.

If he chooses a higher growth rate, he will have to spend more on advertisement and on R & D in order to create more demand and new products.

He will, therefore, retain a higher proportion of total profits for the expansion of the firm. Consequently, profits to be distributed to shareholders in the form of dividends will be reduced and the share prices will fall. The threat of take-over of the firm will loom large among the managers.

As the managers are concerned more about their job security and growth of the firm, they will choose that growth rate which maximises the market value of shares, give satisfactory dividends to shareholders, and avoid the take-over of the firm.

On the other hand, the owners (shareholders) also want balanced growth of the firm because it ensures fair return on their capital. Thus the goals of the managers may coincide with that of owners of the firm and both try to achieve balanced growth of the firm.

Criticism:

Marris’ growth-maximisation theory has been severely criticised for its over-simplified assumptions.

1. Marris assumes a given price structure for the firms. He, therefore, does not explain how prices of products are determined in the market.

2. It ignores the problem of oligopolistic interdependence of firms.

3 This model also does not analyse interdependence created by non-price competition.

4. The model assumes that firms can grow continuously by creating new products. This is unrealistic because no firm can sell anything to the consumers. After all, consumers have their preferences for certain brands which also change when new products enter the market.

5. The assumption that all major variables such as profits, sales and costs increase at the same rate is highly unrealistic.

6. It is also doubtful that a firm would continue to grow at a constant rate, as assumed by Marris. The firm might grow faster now and slowly later on.

Despite these criticisms, Marris’ theory is an important contribution to the theory of the firm in explaining how a firm maximises its growth rate.

Business Firm: Objective # 4.

Baumol’s Sales Maximisation:

Baumol’s findings of oligopoly firms in America reveal that they follow the sales maximisation objective. According to Baumol, with the separation of ownership and control in modern corporations, managers seek prestige and higher salaries by trying to expand company sales even at the expense of profits.

Being a consultant to a number of firms, Baumol observes that when asked how their business went last year, the business managers often respond, “Our sales were up to three million dollars”. Thus, according to Baumol, revenue or sales maximisation rather than profit maximisation is consistent with the actual behaviour of firms.

Baumol cites evidence to suggest that short-run revenue maximisation may be consistent with long-run profit maximisation. But sales maximisation is regarded as the short-run and long-run goal of the management. Sales maximisation is not only a means but an end in itself. He gives a number of arguments is support of his theory. According to him, a firm attaches great importance to the magnitude of sales and is much concerned about declining sales.

If the sales of a firm are declining, banks, creditors and the capital market are not prepared to provide finance to it. Its own distributors and dealers might stop taking interest in it. Consumers might not buy its products because of its unpopularity. But if sales are large, the size of the firm expands which, in turn, means larger profits.

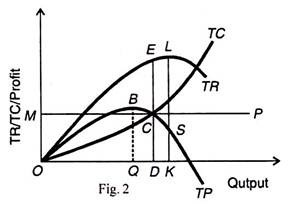

Baumol’s model is illustrated in Figure 2 where TC is the total cost curve, TR the total revenue curve, TP the total profit curve and MP the minimum profit or profit constraint line. The firm maximises its profits at OQ level of output corresponding to the highest point В on the TP curve. But the aim of the firm is to maximise its sales rather than profits.

Its sales maximisation output is OK where the total revenue KL is the maximum at the highest point of TR. This sales maximisation output OK is higher than the profit maximisation output OQ. But sales maximisation is subject to minimum profit constraint.

Suppose the minimum profit level of the firm is represented by the line MP. The output OK will not maximise sales as the minimum profits OM are not being covered by total profits KS.

For sales maximisation, the firm should produce that level of output which not only covers the minimum profits but also gives the highest total revenue consistent with it. This level is represented by OD level of output where the minimum profits DC (=OM) are consistent with DE amount of total revenue at the price DE/OD, (i.e., total revenue/total output).

Criticism:

The sales maximisation objective of the firm has been criticised on a number of points. First, Rosenberg has criticised the use of the profit constraint for maximising sales. He has shown that it is difficult to specify exactly the relevant profit constraint for a firm, and choose the sales maximisation and minimum profit constraint in Baumol’s analysis.

Second, if expenditure on advertising is introduced in Baumol’s theory, the likelihood of sales maximisation is increased.

But this view of Baumol is not realistic because the expenditure on advertising increases or decreases with the rise or fall in output.

Third, the objective of sales maximisation subject to profit constraint implies that “the firm will not make any sacrifice in sales no matter how large an increment in wealth would thereby be achievable.” Despite these criticisms, the sales maximisation is an important objective being pursued by business firms.

Business Firm: Objective # 5.

Output Maximisation:

Milton Kafolgis suggests output maximisation as the objective of a business firm. According to him, “The performance of firms frequently is measured directly in terms of physical output with revenue occupying a secondary position.” Thus Kafolgis prefers output maximisation both to profit maximisation and revenue maximisation as the objective of a firm.

Given some minimum level of profits, a firm wants to maximise its output. It will spend its funds on increasing its production rather than on advertising. Thus the firm will produce a larger output and its revenue sales may be less than the sales-maximisation firm.

Criticism:

Kafolgis’ emphasis on output maximisation as against Baumol’s sales maximisation is not a satisfactory explanation of the objective of a firm. If the firm simply aims at output maximisation without sales maximisation, it may not be in a position to survive for long. Both the objectives are complementary rather than competitive.

Second, if the firm is a multiproduct firm how the output of different products, say radio, TV, and watches can be added. It is only the value of sales of each product that can be added together. This is nothing but maximisation of sales.

Business Firm: Objective # 6.

Security Profits:

Rothschild has put forward the view that the firm is motivated not by profit maximisation but by the desire for security profits. In his words, “There is another motive which is probably of a similar order of magnitude as the desire for maximum profits, the desire for security profits.”

Rothschild argues that so far as the objective of profit maximisation is concerned, it is valid only under perfect competition or monopolistic competition in which the number of firms is very large, and the individual firm is not faced with the security problem, so is the case with the monopoly firm.

But under oligopoly, a firm is not motivated by profit maximisation. It is engaged in a constant struggle to achieve and maintain a secure position in the market like a military strategist.

The desire to increase its security leads to the struggle for position and to the setting of a price which will not be so low that it provokes retaliation from rivals, nor so high that it encourages new entrants, and it must be within the range which will maintain a protection against the aggressive policies of the rivals and brine about a reasonable profit above its cost of production Rothschild’s security-profits motive is nothing else but profit maximisation in a little different garb.

Business Firm: Objective # 7.

Satisfaction Maximisation:

Scitovsky favours maximisation of satisfaction in preference to the profit-maximisation objective of the firm. He is concerned with managerial effort and the distaste that managers have for work. According to him an entrepreneur would maximise profits only if his choice between more income and more leisure is independent of his income. In other words, the supply of entrepreneurship should have zero income elasticity.

But an entrepreneur does not aim at profit maximisation. He wants to maximise satisfaction and keep his efforts and output below the level of maximum profits.

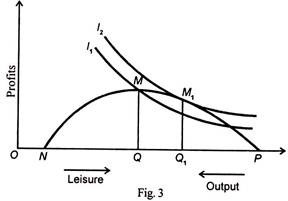

This is because as his income (profit) increases, he prefers leisure to effort (output) Scitovsky’s maximisation of satisfaction hypothesis is illustrated in Fig 3 where NP is the net profit (income) curve, the difference between the TR and TC curves, which have not been drawn to simplify the analysis. Thus profits are measured on the vertical axis.

Assuming managerial effort and output to be proportional output is measured along the horizontal axis from P toward О so that at point P output is zero. Since more efforts mean less leisure, and vice versa, leisure is also measured on the horizontal axis from О toward P.

The curves L1 and L2 are the entrepreneur’s indifference curves which represent his levels of satisfaction yielding combinations of his money income (profits) and leisure.

The entrepreneur’s satisfaction would be the greatest at the level of output where the net profit curve is tangential to an indifference curve. In the figure, M is his point of maximum satisfaction where the net profit curve NP is tangent to his indifference curve L2. He will be producing PQ1 output.

This level of output is less than the profit-maximisation output PQ. The entrepreneurial profits, Q1M1, at PQ1 output level are also less than the maximum profits QM at PQ level of output. At Q1M1, level of profit, the entrepreneur maximises his satisfaction because he enjoys OQ1 leisure which is QQ1 more than he would have enjoyed under profit maximisation (OQ).

Criticism:

Scitovsky has himself pointed out two weaknesses in his satisfaction maximisation theory first; it is unrealistic to assume that entrepreneur’s willingness to work is independent of his income. After all the ambition of an entrepreneur to make money cannot be dampened by a rising income.

Second, to say that an entrepreneur maximises his satisfaction is a perfectly general statement, it says nothing about his psychology or behaviour. Therefore, it is only a truism and is devoid of any empirical content.