We saw that, in the absence of collusion, the monopoly solution in the industry (the solution at which the joint industry profit is maximized) can be achieved under the rare conditions that;

(a) each firm knows the monopoly price, that is, has a correct knowledge of the market demand and of the costs of all firms,

(b) that each firm recognizes its interdependence with the others in the industry,

(c) all firms have identical costs and identical demands. (Actually condition (c) implies condition (a))

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We will examine two typical forms of cartels:

(a) Cartels aiming at joint-profit maximization, that is, maximization of the industry profit, and

(b) Cartels aiming at the sharing of the market.

A. Cartels aiming at joint-profit maximization:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

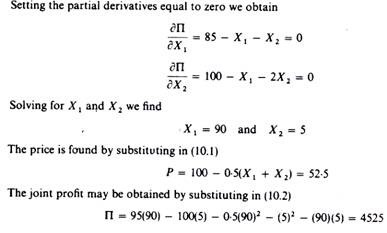

Cartels imply direct (although secret) agreements among the competing oligopolist with the aim of reducing the uncertainty arising from their mutual interdependence. In this particular case the aim of the cartel is the maximisation of the industry (joint) profit. The situation is identical with that of a multiplant monopolist who seeks the maximisation of his profit. We concentrate on a homogeneous or pure oligopoly, that is, an oligopoly where all firms produce a homogeneous product. The case of differentiated oligopoly will be examined in a separate section.

The firms appoint a central agency, to which they delegate the authority to decide not only the total quantity and the price at which it must be sold so as to attain maximum

group profits, but also the allocation of production among the members of the cartel, and the distribution of the maximum joint profit among the participating members.

The authority of the central cartel agency is complete. Clearly the central agency will have access to the cost figures of the individual firms, and for the purposes of the present theory we unrealistically suppose that it will calculate the market-demand curve and the corresponding MR curve. From the horizontal summation of the MC curves of individual firms the market MC curve is derived.

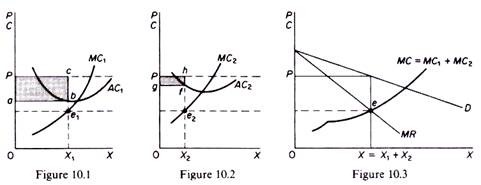

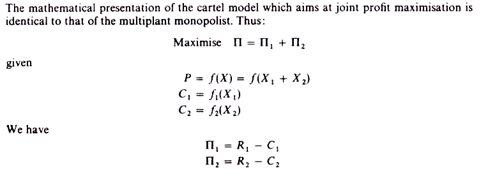

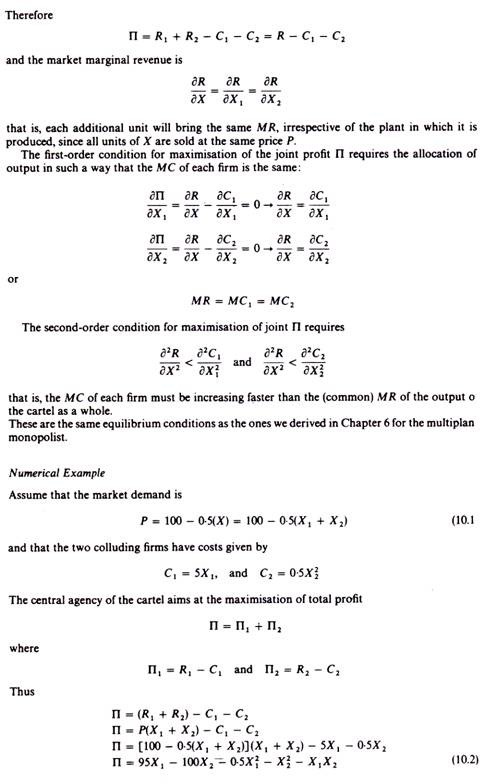

The central agency, acting as a multi- plant monopolist, will set the price defined by the intersection of the industry MR and MC curves. For simplicity assume that there are only two firms in the cartel. Their cost structure is shown in figures 10.1 and 10.2. From the horizontal summation of the MC curves we obtain the market MC curve.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is implied by the profit-maximisation goal of the cartel each level of industry output should be produced at the least possible cost. Thus if we add the outputs of A and B that can be produced at the same MC, clearly the resulting total output is the output that can be produced at this common lowest cost. Given the market demand DD (in figure 10.3) the monopoly solution, which maximises joint profits, is determined by the intersection of MC and MR (point e in figure 10.3).

The total output is X and it will be sold at price P. Now the central agency allocates the production among firm A and firm B as a monopolist would do, that is, by equating the MR to the individual MCs. Thus firm A will produce X1 and firm B will produce X2. Note that the firm with the lower costs produces a larger amount of output. However, this does not mean that A will also take the larger share of the attained joint profit. The total industry profit is the sum of the profits from the output of the two firms, denoted by the shaded areas of figures 10.1 and 10.2. The distribution of profits is decided by the central agency of the cartel.

Although theoretically the monopoly solution is easy to derive, in practice cartels rarely achieve maximum joint profits. There are several reasons why industry profits cannot be maximised, even with direct cartel collusion.

It should be obvious that equilibrium with joint profit maximisation will be easier to attain and will be in general stable if firms have identical costs and identical demands, conditions that are rarely met in practice. (However, even with identical costs cartels may still be unstable. See below.) Even in these conditions many factors may mitigate against achievement of the joint profit-maximisation goal of the cartel. The main reasons why industry profits may not be maximised may be summarized as follows.

First:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Mistakes in the estimation of market demand. Usually the elasticity of market demand is underestimated. Each firm believes that the e of its own demand curve is high due to the existence of perfect (or almost perfect) substitutes made by competitors, while the industry demand is much less elastic. Clearly, mistakes in the estimation of the market demand lead to mistakes in the derivation of the MR and hence to a price which is higher than the monopoly price.

Second:

Mistakes in the estimation of MC. The estimation of the market MC, from the summation of individual costs, may involve mistakes, due to incomplete knowledge of the individual MC curves at all levels of output. That is, even if a cartel estimated marginal costs, which is highly improbable, it would probably get them wrong.

Such errors lead to an equilibrium which differs from the monopoly solution. There is a strong incentive for the individual members to present low-cost figures to the central agency, since the allocation of output and of profit shares is determined, among others, by the level of costs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Third:

Slow process of cartel negotiations. Cartel agreements take a long time to negotiate due to the differences in size, costs, and markets of the individual firms. During the negotiations each firm is bargaining in order to attain the greatest advantage from the cartel agreement.

Thus, even if at the beginning of the negotiations costs and market demand were correctly estimated, by the time agreement is reached market conditions may have changed, thus rendering the initially denned monopoly price obsolete. Cartel agreements with more than about twenty partners are difficult to reach, and break down easily once reached.

Fourth:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

‘Stickiness’ of the negotiated price. Once the agreement about price is reached, its level tends to remain unchanged over long periods, even if market conditions are changing. This price inflexibility (stickiness) is due to the time-consuming process of cartel negotiations and the difficulties and uncertainties about the bargaining of cartel members.

Fifth:

The ‘bluffing’ attitude of some members during the bargaining process. Some firms may attempt to reduce price, to expand their selling activities and in general to achieve a large market share before the final agreement, so as to achieve the maximum advantage from it. However, such activities have only short-run effects and lead to miscalculations of the real monopoly equilibrium price and output.

Sixth:

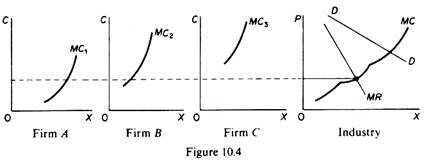

The existence of high-cost firms. If a firm is operating with a cost curve which is higher than the equilibrium MC, clearly this firm should close down if joint profits are to be maximised. (Firm C in figure 10.4 should close down.) However, no firm would join the cartel if it had to close down, even if the other firms agree in allocating to it part of the total profits, because by closing down the firm loses all its customers, and if subsequently the cartel members decide to stop sharing their profits with this member, there is little that he can do about it, since he has to start from scratch in order to attract back his old customers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Seventh:

Fear of government interference. If the monopoly price yields too high profits the cartel members may decide not to charge it, for fear of government interference.

Eighth:

The wish to have a good public image. Similarly the members of the cartel may decide not to charge the profit-maximising price if profits are lucrative, if they wish to have the ‘good’ reputation of charging a ‘fair price’ and realising ‘fair profits’.

Ninth:

Fear of entry. One major reason for not charging the profit-maximising price if it yields too high profits is the fear of attracting new firms to the industry. Since there is great uncertainty regarding the behaviour of the new firm, established firms prefer to sacrifice some of their profits in order to prevent entry.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Tenth:

Keeping freedom regarding design and selling activities. Even if firms adhere to the price defined by the central agency, they usually keep their freedom in deciding the style of their output and their selling activities. Each firm tries to attain higher sales by better service or intensive selling activities. (This holds in particular for differentiated products. See below.) This attitude leads to increased costs, and hence to a decrease in the monopoly profits.

It is clear that there are too many exceptions to the theory of joint profit maximisation for it to be a satisfactory theory of oligopolistic behaviour.

A note on mergers:

The above model of profit-maximising cartel, where output of each member is decided by the central governing body of the cartel on the basis of marginalistic rules, is also applicable to mergers of firms producing the same product. A merger involves the decision of a number of independent firms to form a single corporation. The new firm may act as a cartel it may decide to change the output quota of each plant so as to maximise the overall profit of its operations.

In this process each plant will be allocated a quota defined by the equality of its marginal cost with the common marginal revenue of the corporation created from merger. Under these conditions the difference between a cartel and a merger is only a legal one while overt cartel agreements are illegal in Britain and in the U.S.A., mergers are generally legal.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A merger can be forbidden only if it is proved that its aim is to restrict competition and earn abnormal monopoly profits. However, mergers are usually rationalised on grounds of better utilisation of resources and attainment of economies of scale, and thus are allowed to take place more often than not.

While the above model may be applied to mergers in theory, it is not certain that the implied reallocation of resources and output will actually take place. The analysis of the motives of mergers and their actual operation goes beyond the scope of this book.

B. Market-sharing cartels:

This form of collusion is more common in practice because it is more popular. The firms agree to share the market, but keep a considerable degree of freedom concerning the style of their output, their selling activities and other decisions.

There are two basic methods for sharing the market non-price competition and determination of quotas.

Non-price competition agreements:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this form of ‘loose’ cartel the member firms agree on a common price, at which each of them can sell any quantity demanded. The price is set by bargaining, with the low-cost firms pressing for a lower price and the high-cost firms for a high price. The agreed price must be such as to allow some profits to all members.

The firms agree not to sell at a price below the cartel price, but they are free to vary the style of their product and/or their selling activities. In other words, the firms compete on a non-price basis. By keeping their freedom regarding the quality and appearance of their product, as well as advertising and other selling policies, each firm hopes that it can attain a higher share of the market.

This form of cartel is indeed loose’, in the sense that it is more unstable than the complete cartel aiming at joint profit maximisation. If all firms have the same costs, then the price will be agreed at the monopoly level. However, with cost differences the cartel will be inherently unstable, because the low-cost firms will have a strong incentive to break away from the cartel openly and charge a lower price, or to cheat the other members by secret price concessions to the buyers.

However, such cheating will soon be discovered by the other members of the cartel, who will gradually lose their customers. Thus others may split away from the cartel, and a price war and instability may develop until only the fittest low-cost firms survive. Another possibility is that the members of the cartel in conjunction may decide to start a price war until the firm which split off or cheated is driven out of business.

Whether this policy will be successful depends on the cost differential (cost advantage) of the splitter relative to the other cartel members as well as on the liquidity position and the ability of obedient members to finance possible losses during the period of the price war.

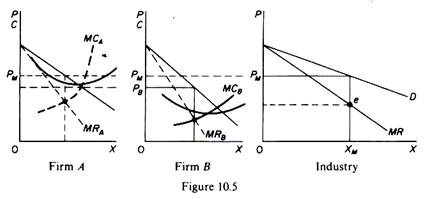

In figure 10.5 firm B has lower costs than A, and hence B will have the incentive to cut the price below the monopoly level, thus driving the high-cost competitor A out of business.

Even with the same cost structure these cartels are inherently unstable, because if one firm splits away and charges a slightly lower price than the monopoly price PM while the others remain in the cartel, the splitting firm will attract a considerable number of customers from the others its demand curve will be much more elastic and its profits will be increased. All firms will have the same incentive to leave the cartel, which thus becomes inherently unstable, unless supported by tight legislation. With open collusion being illegal it is not surprising that cartels are usually short-lived.

Sharing of the market by agreement on quotas:

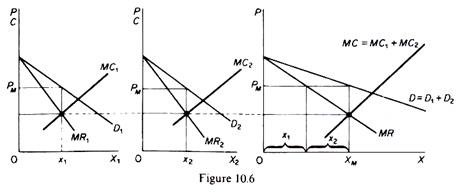

The second method for sharing the market is the agreement on quotas, that is, agreement on the quantity that each member may sell at the agreed price (or prices). If all firms have identical costs, the monopoly solution will emerge, with the market being shared equally among member firms. For example, if there are only two firms with identical costs, each firm will sell at the monopoly price one-half of the total quantity demanded in the market at that price.

In figure 10.6 the monopoly price is PM and the quotas which will be agreed are X1 = X2 = ½ XM. However, if costs are different, the quotas and shares of the market will differ. Allocation of quota-shares on the basis of costs is again unstable. Shares in the case of cost differentials are decided by bargaining. The final quota of each firm depends on the level of its costs as well as on its bargaining skill. During the bargaining process two main statistical criteria are most often adopted quotas are decided on the basis of past levels of sales, and/or on the basis of ‘productive capacity’. The ‘past-period sales’ and/or the definition of ‘capacity’ of the firm depends largely on their bargaining power and skill.

Another popular method of sharing the market is the definition of the region in which each firm is allowed to sell. In this case of geographical sharing of the market the price as well as the style of the product may differ. There are many examples of regional market-sharing cartels, some operating at international levels.

However, even a regional split of the market is inherently unstable. The regional agreements are often violated in practice, either by mistake or intentionally, by the low-cost firms who have always the incentive to expand their output by selling at a lower price openly defined, or by secret price concessions, or by reaching adjacent markets through advertising.

It should be obvious that the cartel models of collusive oligopoly are ‘closed’ models. If entry is free, the inherent instability of cartels is intensified: the behaviour of the entrant is not predictable with certainty. It is not certain that a new firm will join the cartel.

On the contrary, if the profits of the cartel members are lucrative and attract new firms in the industry, the newcomer has a strong incentive not to join the cartel, because in this way his demand curve will be more elastic, and by charging a slightly lower price than the cartel he can secure a considerable share in the market, on the assumption that the cartel members will stick to their agreement.

Cartels, being aware of the dangers of entry, will either charge a low price so as to make entry unattractive, or may threaten a price war on the newcomer. If entry occurs and the cartel carries out its threat of price war, the newcomer may still survive, depending on his cost advantage, and his financial strength in withstanding possible losses during the initial period of his establishment, until he reaches the size which will allow him to reap the full ‘scale economies’ that he has over those enjoyed by existing firms.