The following points highlight the top four techniques of credit control adopted by central bank. The techniques are: 1. The Bank Rate 2. Open Market Operations 3. Variable Reserve Ratio 4. Selective or Qualitative Methods of Control.

Credit Control Technique # 1. The Bank Rate:

A commercial bank’s customer gets money by discounting eligible bills of exchange or other commercial papers from it. Similarly, a commercial bank gets money by rediscounting bills from the central bank. Bank rate is the minimum lending rate of the central bank at which it rediscounts bills. By “turning the bank rate screw” the central bank can expand or reduce the volume of credit.

Suppose, commercial banks have decided to undertake more discounting of bills to earn maximum profit. More and more discounting of bills means an increase in the volume of credit. If the central bank—in the interest of the country, thinks that this is undesirable, it will raise the bank rate.

Commercial banks will also raise their own rates of interest. Consequently, people will take fewer loans and advances.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, there will be a credit contraction. Likewise, credit supply will increase if bank rate is lowered down. Whenever the bank rate is changed, commercial banks also change their own or short term rates of interest. Thus, bank rate is a quantitative credit control instrument that can influence the volume of credit.

Bank rate affects the demand for credit, supply or cost of credit, and the availability of credit in the following way:

Once bank rate is raised, commercial banks’ demand for central bank money by discounting bills will decline. This, in fact, will reduce credit-creating powers of the commercial banks. Further, a higher bank rate means higher short term interest rates.

Thus high bank rate deters borrowers from borrowing and, hence, demands for credit declines. Opposite sequence of events come into play when bank rate is lowered down. That is to say, credit demand rises (falls) once the bank rate is reduced (increased).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Bank rate influences supply or cost of credit. There is a rigid relationship between the bank rate and other short term rates of interest charged by commercial banks. A rise (or fall) in bank rate is accompanied with a rise (or fall) in market rates of interest. This results in increased (or lower) cost of credit which would reduce (or increase) credit supply.

Again, a rise in bank rate can be thought of as a prelude to a smaller availability of credit. Lenders of the money market then follow a cautious lending policy. Credit can be expanded by a reduction in bank rate.

As a general rule, bank rate is raised during inflation and lowered during recession. Thus, the bank rate is a double- edged weapon.

Limitations:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, bank rate changes may not be as effective as it appears.

Successful functioning of bank rate operation depends on two conditions:

i. There must be a close and direct relationship between bank rate changes and other short term interest rates; and

ii. Money market and capital market must be developed.

In an underdeveloped money market, bank rate and market rates of interest do not move in the same direction. Commercial banks may not find any urgency for discounting bills whenever they experience surplus cash with them.

Under the circumstances, bank rate changes have little effect on the economy. However, in a country like India, money market is no longer in infancy or in an under-developed state. Further, commercial banks are efficiently controlled and regulated by the central bank.

But investment decisions in public sector industries are not influenced by bank rate consideration. Rather, socio-eco-political factors, in tandem, determine investment in these industries. Thus, bank rate is of little use.

In some underdeveloped countries, commercial banks habitually maintain excess cash reserves at their disposal. Under the circumstance, commercial banks do not find great urgency of taking credit by discounting bills from the central bank. If so, a change in the bank rate fails to influence the volume of credit.

Finally, bank rate may not be successful in controlling cost-push inflation. Bank rate may be effective in controlling demand-pull inflation. Bank rate has, in fact, no influence over the cost factors.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Despite these limitations, it is an important quantitative credit control instrument in the kitty of a central bank.

Credit Control Technique # 2. Open Market Operations:

By open market operations (henceforth OMO) we mean purchase and sale of securities in the open market by the central bank on its own initiative. Thus, OMO consists of two types: open market purchase, and open market sale.

When the central bank purchases government securities in the open market, money flows out from the pocket of the central bank to the sellers of securities (who may be commercial banks, non-banking financial intermediaries, general public, etc.).

In other words, the central bank injects more money in the economy by conducting open market purchase policy. Similarly, when the central bank sells securities in the open market, commercial banks, public and non-banking financial institutions pay money to the central bank for the purchase of securities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As a result, the government’s account with the central bank goes up by the value of securities sold. In other words, open market sale policy is conducted by the central bank to siphon off the money supply. Thus, like bank rate, OMO is also a double-edged weapon—open market purchase policy is adopted during deflation and open market sale policy at the time of inflation.

OMO influences money market in two ways. Firstly, it produces a ‘quantity effect’. Whenever open market purchase and sales are conducted, cash reserve position or liquidity position of commercial banks undergoes a change. In other words, money supply or lending power of commercial banks expands and contracts.

This is the ‘quantity effect’ of OMO. Secondly, open market purchase or sale is accompanied with a change in long term interest rates which have an important bearing on the economy. This is the ‘interest effect’ of OMO which influences the demand for credit, supply or cost of credit and availability of credit.

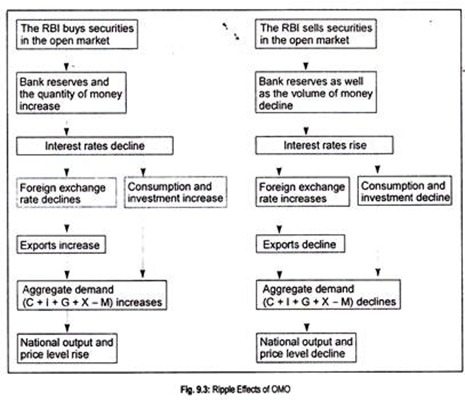

Schematically, the effects of OMO on the economy may be better understood if we study Fig. 9.3.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This credit control instrument is used by the central bank

(i) To make the bank rate effective.

(ii) To provide seasonal finance in the economy.

(iii) To ensure stability in prices and interest rates of government securities.

(iv) To assist in the debt management policy of the government, etc. However, this last objective is, of course, the fiscal objective of the weapon.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Merits:

One of the chief merits of OMO is that it controls the lending activities of non-banking financial intermediaries which remain virtually unregulated by the central bank.

These institutions are good providers of money supply in an economy. No other credit control instrument can control them. OMOs are both precise and flexible; they can be used to any extent, either in small or in large doses.

Demerits:

However, for the success of this instrument of credit control, certain conditions are to be fulfilled. Firstly, security market must be developed.

Secondly, commercial banks must not maintain excess cash-deposit ratio over the legal minimum reserve requirement. In reality, since these two conditions are never met in underdeveloped countries, OMOs become a rather ineffective instrument in the attainment of credit control objectives.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Again, this technique becomes limited when the central bank possesses limited amount of securities. Above all, this credit control instrument is employed as a public debt management device rather than monetary control. In view of all these reasons, this technique is not so popular in many LDCs.

Credit Control Technique # 3. Variable Reserve Ratio:

Commercial banks are required by law or by convention to keep a part of their deposits with the central bank as reserves. This is called legal minimum cash reserve ratio (CRR). If the commercial banks have excess reserves, an increase in CRR will reduce their lending potential.

On the other hand, whenever CRR is reduced, the commercial banking system acquires additional reserves than before which make an expansion of credit possible. Thus, the variation in CRR is also a double-edged weapon. This technique, compared to other instruments of control, puts “direct possible pressure” on commercial banks in the desired direction.

The technique of CRR is comparatively better than other instruments since it does not require well-organized money market and security market for its efficient functioning. In this sense, it scores good marks over other instruments. That does not mean it is limitation-free. For instance, it may produce ‘shocks’ in the business world. A rise (fall) in CRR impounds (releases) excess reserves.

Faced with lower (larger) excess reserves, commercial banks may suffer from liquidity crisis or enjoy huge cash reserves. Frequent changes in CRR may thus produce undesirable effects in the economy. Further, CRR may produce negligible effect on the money supply when commercial banks keep excess cash reserves. However, with proper caution and wisdom, it can be made a useful credit control instrument.

However, these three weapons are not to be considered as competitive; rather, they are complementary to each other.

Credit Control Technique # 4. Selective or Qualitative Methods of Control:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The above-mentioned quantitative methods are known as general methods of the credit control since a change of these instruments in any direction affect the entire economy. But, underdeveloped countries experience fluctuations in economic activities in a particular sector or group of sectors. Under the circumstances, these particular sectors of the economy demand control and regulation.

Qualitative or selective methods of control are better in this direction since these put pressures only on certain sectors of the economy, without regulating the flow of credit to the unaffected sectors. Hence the name selective credit control. From this point of view, quantitative methods may be designated as a ‘general therapy’ while selective method as a ‘local therapy’.

Underdeveloped countries are inflation- sensitive countries. As economic development proceeds, certain sectors experience inflationary trends.

To make the credit dearer in those sectors, central bank deploys selective methods of credit control without regulating the flow of credit in other sectors which are now free from inflationary tendencies. Further, this technique has the great potential in curbing consumption expenditure which is an important component of inflation.

Limitations:

Firstly, final use of credit cannot be ensured through this technique. Secondly, some believe that this technique can only control inflation. It is ineffective in controlling deflationary tendencies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thirdly, often commercial banks of underdeveloped countries fail to comply the directives of the central bank. Even if they follow the directives, it takes a long time to implement the order. Thus the purpose of the technique is defeated.

However, this drawback is not unique to this credit control technique. More or less, all the credit control instruments become less effective since time lag exists between the initiation of the central bank order and its implementation.