Read this article to learn about Demand and Supply of Labour which are explained with diagrams!

Although labour has certain peculiarities and cannot be regarded as a commodity, still wages are very largely determined by the interaction of the forces of demand and supply.

Demand for Labour:

The demand for labour is a derived demand. It is derived from demand for the commodities it helps to produce. The greater the consumers’ demand for the product, the greater the producers’ demand for the labour required in making it. Hence an expected increase in the demand for a commodity will increase the demand for the type of labour that produces this commodity.

The elasticity of demand for labour depends, therefore, on the elasticity of demand for its output. Demand for labour will generally be inelastic if their wages form only a small proportion of the total wages. The demand, on the other hand, will be elastic if the demand for the commodity it produces is elastic or if cheaper substitutes are available.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The demand for labour also depends on the prices of the co-operating factors. Suppose the machines are costly, as is the case in India, obviously more labour will be employed. The demand for labour will increase. Another factor that influences the demand for labour is the technical progress. In some cases, labour and machinery are used in a definite ratio. For instance, the introduction of automatic looms reduces the demand for labour.

After considering all relevant factors, e.g., demand for the products, technical conditions, and the prices of the co-operating factors, the wages are governed by one fundamental factor, viz., marginal productivity. Just as there is a demand price of commodities, so there is a demand price for labour.

The demand for labour, under typical circumstances of a modern community, comes from the employer who employs labour and other factors of production for making profits out of his business. The demand price of labour, therefore, is the wage that an employer is willing to pay for that particular kind of labour.

Suppose an entrepreneur employs workers one by one. After a point, the law of diminishing marginal returns will come into operation. Every additional worker employed will add to the total net production at a decreasing rate. The employer will naturally stop employing additional workers at the point at which the cost of employing a worker just equals the addition made by him to the value of the total net product.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, the wages that he will pay to such a worker (the marginal unit of labour) will be equal to the value of this additional product or marginal productivity. But since all the workers may be assumed to be of the same grade, what is paid to the marginal worker will be paid to all the workers employed. This is all about the demand side of labour. Now let us consider the supply side.

Supply of Labour:

By the supply of labour, we mean the various numbers of workers of a given type of labour which would offer themselves for employment at various wage rates.

The supply of labour may be considered from two view-points?

(a) Supply of labour to the industry and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Supply of labour to the entire economy.

For an industry, the supply of labour is elastic. Hence, if a given industry wants more labour, it can attract it from other industries by offering a higher wage. It can also work the existing labour force over-time. This in effect will mean an increase in supply. The supply of labour for the industry is subject to the law of supply, i.e., low wage, small supply and high wage, large supply. Hence, the supply curve of labour for an industry rises upwards from left to right.

The supply of labour for the entire economy depends on economic, social and political factors or institutional factors, e.g., attitude of women towards work, working age, school and college leaving age and possibilities of part-time employment for students, size and composition of the population and sex distribution, attitude to marriage, the size of the family, birth control, standard of medical facilities and sanitation, etc.

The supply of labour may be decreased by workers refusing to work for a time. This happens when labour is organised into trade unions. The workers may not accept wages offered by the employer if such wages do not ensure the maintenance of a standard of living to which they are accustomed.

But, as we shall see, it is only when higher wages are justified by higher marginal productivity that high wages will be paid. Thus, workers with low marginal productivity cannot demand high wages merely on the basis of their standard of living. On the whole, we might say that, the number of potential workers being given, the supply of labour may be defined as the schedule of units of labour at the prevailing rates of wages.

This depends on two factors:

(a) The number of workers who are willing and able to work at different wages;

(b) The number of working hours that each Worker is willing and able to put in at different wages.

In case the workers have no staying power and the only alternative to work is starvation, the supply of labour in general will be perfectly inelastic. This means that wages can he driven down. Over a short period, reduction in wages may not cause any reduction in the supply of labour. For any industry over a long period, the supply curve will slope upwards from left to right. In other words, supply will be somewhat elastic in the long run.

Backward Sloping Supply Curve of Labour:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

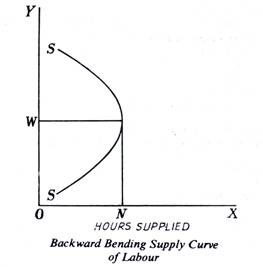

While labour’s supply curve sloping upwards from left to right is the general rule, an exceptional case of labour’s supply curve may also be indicated (see Fig. 31.1) When the workers’ standard of living is low, they may be able to satisfy their wants with a small income and when they have made that much, they may prefer leisure to work. That is why it happens that, sometimes, increase in wages leads to a contraction of the supply of labour. This is represented by a backward-sloping supply curve as under.

For some time this particular individual is prepared to work long hours as the wage goes up (wage is represented on OY—axis in Fig. 31.1). But beyond OW wage, he will reduce rather than increase his working hours.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, this backward sloping Curve may sometimes be true of certain workers, the supply curve of labour to industry as a whole will normally slope upwards from left to right (as shows in Fig. 31.2)

Interaction of Demand and Supply:

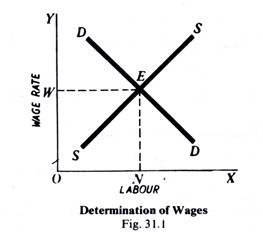

We have now analysed the demand side as well as the supply side of labour. We shall now see how their interaction determines the wage level. This is shown in Fig. 31.2

In this diagram, we have shown the wage determination of a particular type of labour for an industry. The curve SS represents supply of labour to the industry. DD is the demand curve for labour of that industry. Demand and supply curves intersect at E. Therefore, the wage rate OW (= NE) will be established. The equilibrium wage rate will change if the demand and/or supply conditions change.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

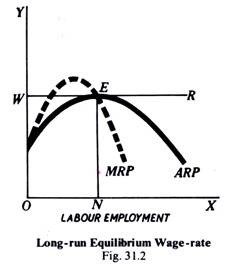

Under competitive conditions, wage rate in the long run will be equal to both the marginal revenue product and the average revenue product. If the wage rate is less than the average revenue product, the firms would be earning supernormal profits. As a result, new firms will enter the industry and the demand for labour will increase which will push up the wage rate so as to be equal to average revenue product.

On the other hand, if the wage rate is above the average revenue product, the firms will be suffering losses. As a result, some firms will leave the industry and demand for labour will decrease which will force the wage-rate down. Fig. 31.2 shows the long-run equilibrium of the firms under perfect competition. This diagram shows that long-run equilibrium wage rate is OW. At wage rate OW, the firm is employing ON number of labour. This OW rate is equal to marginal revenue product (MRP) and average revenue product (ARP) at point E. The point E is the equilibrium position of the firm in the long run.

We have so far concerned ourselves with the problem of how wages in general are determined. But is there any general rate of wages?

If labour had been like any other commodity, it would also have been sold in the market at the same rate. But as you know, labour is peculiar in certain respects. Labourers differ in efficiency. They are less mobile than goods. Their supply cannot be increased to order and it is a most painful process to reduce I hem. If a day is lost, its labour is lost with it. For these and other reasons, a uniform rate of earnings for workers is not possible. There is thus no prevailing rate of wages similar to the prevailing rate of interest or prevailing price of a good.

All over the world, labour is spat up into a very large number of groups and sub-groups, each with a different level of wages. Even within the same group, the differences are ever so many. Consequently there cannot possibly be a general rate of wages. All that can be done is to and out an average rate which can be discovered by dividing the total amount paid to a given group of workers by the total number of workers in it. The fact is that the wages differ from occupation to occupation. Wages are relative.