In this article we will discuss about the aggregation problem of market demand, explained with the help of a diagram.

The aggregation of individual demand curves for a good to obtain its market demand curve by means of horizontal summation of the individual curves would pose no problems if the individual demand curves are independent.

But, if these curves are not independent, for example, if individual B’s purchases depend on A’s purchases, either because B is jealous of A and tries to keep up with A in consumption or because B’s income depends in some way on A’s purchase, then it cannot simply take the horizontal summation of the individual curves to obtain the market demand curve.

For, now observe how a shift in the demand curve of one individual affects the demand curves of others, would have an aggregation problem. The most convenient solution to this problem is to assume away the problem.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Actually, most pure theory proceeds on the assumption that the individual demand curves are independent and their formal axiom here is that consumers’ preferences are selfish.

By this axiom, it is assumed that a particular consumer’s preferences are not influenced by the consumption levels of others, and the consumers do not judge quality by price, i.e., it is not that the consumers buy more at higher prices because a higher price indicates a higher quality.

However, simple observations and introspections suggest that this axiom is severely restrictive. The axioms, in general, involve oversimplification, but the axiom of selfishness implies a substantial departure from reality.

Therefore, what happens to the theory of consumer behaviour if the selfishness axiom is relaxed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

First, it may be assumed that an individual purchases goods in order to behave like other members of his social group. If their demand for a good increases, so will his, since he wishes to identify with them. This effect is known as the bandwagon effect.

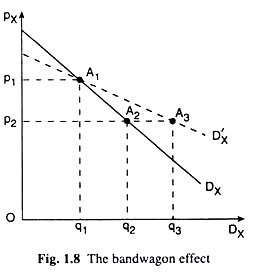

The effect with the help of Fig. 1.8, where DX is the market demand curve for a good X under the axiom of selfishness, or under the absence of interdependencies. Along this demand curve, at the point A, the market demand for the good is q, at the price p1 and if price falls from p1 to p2, move from the point A1 to A2, and the market demand for the good would increase from q1 to q2.

This is because a large section of the existing customers, if not all of them, will want to purchase more of the good now that its price has fallen. Besides, some new but selfish buyers would enter the market to have the good at a lower price.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, if there is the bandwagon effect, a large number of new customers driven by the desire to keep up with the Joneses will enter the market, and the demand for the good at the price of p2 will exceed q2.

If the demand for the good becomes q3 > q2, then the market demand curve would be the curve DX passing through A1 (p1, q1) and A3 (p2, q3). This market demand curve, DX, would be more flat and more elastic than the original curve, viz., DX. So the bandwagon effect makes the market demand curve more elastic.

A second case of violation of selfishness axiom occurs if the consumer attempts to make himself different from other members of his social group by purchasing the commodities which they do not purchase, and, conversely, by reducing the purchase of the goods which they purchase, i.e., if the consumer behaves like a snob.

The effect of such behaviour of the consumer is known as the snob effect, this effect can be illustrated with the help of Fig. 1.9.

Here the market demand curve when the snob effect did not exist is DX. Along this demand curve, the market demand for the good is q1 at the price p1—this is at the point A1, and if the price falls to p2, the market demand would rise to q2, i.e., move from the point A1 to the point A2 along the curve DX.

However, if some of the buyers of the good behaved like snobs, then demand at the price p2 would not have increased to q2, it would have been somewhat less, say, q3 (q3 < q2). Therefore, if the snob effect exists, the demand curve would not pass through A1 and A2, it would pass through the points A1 (p1, q1) and A3 (p2, q3). Since q3 < q2, the snob effect makes the demand curve more steep and less elastic.

Lastly, a case of consumer’s lack of independence where he judges the quality of a good by its price. The effect upon the market demand for the good that is obtained here is known as the Veblen effect after the economist Thorstein Veblen.

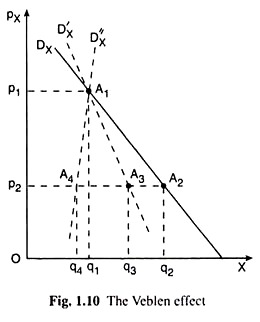

The Veblen effect can be illustrated with the help of Fig. 1.10. In this figure, the curve DX is the market demand curve that would be obtained as the horizontal summation of the individual demand curves, i.e., if the axiom of selfishness prevailed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At the point A1 on this demand curve, the price-demand combination is (p1q1), and if price comes down from p1 to p2, then at the point A2, demand would increase from q1 to q2. But if there is Veblen effect, the fall in the price from p1 to p2 would induce some of the consumers to think that the quality of the good has worsened and they will reduce their quantities purchased of X.

Because of this, demand for the good at the price of p2 will not be equal to q2, but it would be somewhat less; let us suppose it would be q3. Therefore, the market demand curve, instead of being DX, would be DX which would pass through the points A1 and A3 and it would be steeper than DX, but downward sloping. Therefore, the Veblen effect, generally, makes the demand curve less elastic.

A stronger Veblen effect may, of course, make the market demand curve positively sloped, i.e., it would generate an exception to the law of demand.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Fig. 1.10, this case would be obtained, if, as price falls from p1 to p2, some of the consumers may think so strongly of a quality fall that the quantity demanded would be as small as q4 so that by joining the points A1 and A4, a positively sloped demand curve, viz., DX.

If the consumers’ choices and buying plans are interdependent, the true market demand curve would diverge from the horizontal summation of the individual demand curves.

However, the extent of such divergence would depend on the strength of the bandwagon, snob and Veblen effects and on the number of individuals subject to such effects. Note here that the market is composed of a large number of independent buyers. Therefore, it is most likely that all the three effects may work together along with the normal consumer behaviour.