Samuelson’s revealed preference theory has preference hypothesis as a basis of his theory of demand.

According to this hypothesis, when a consumer is observed to choose a combination A out of various alternative combinations open to him, then he ‘reveals’, his preference for A over all other alternative combinations which he could have purchased.

In other words, when a consumer chooses a combination A, it means he considers all other alternative combinations which he could have purchased to be inferior to A. That is, he rejects all other alternative combinations open to him in favour of the chosen combination A. Thus, according to Samuelson, choice reveals preference. Choice of the combination A reveals his definite preference for A over all other rejected combinations.

From the hypothesis of ‘choice reveals preference’ we can obtain definite information about the preferences of a consumer from the observations of his behaviour in the market. By comparing preferences of a consumer revealed in different price-income situations we can obtain certain information about his preference scale.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

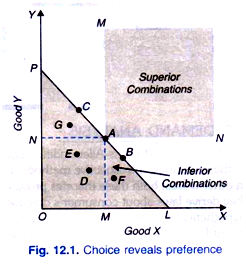

Let us graphically explain the preference hypothesis. Given the prices of two commodities X and Y and the income of the consumer, price line PL is drawn in Fig. 12.1. The price line PL represents a given price-income situation. Given the price-income situation as represented by PL, the consumer can buy or choose any combination lying within or on the triangle OPL.

In other words, all combinations lying on the line PL such as A, B, C and lying below the line PL such as D, E, F and G are alternative combinations open to him, from among which he has to choose any combination. If our consumer chooses combination A out of all those open to him in the given price-income situation, it means he reveals his preference for A over all other combinations such as B, C, D, E and F which are rejected by him. As is evident from Fig. 12.1, in his observed chosen combination A, the consumer is buying OM quantity of commodity X and ON quantity of commodity Y.

Besides, we can infer more from consumer’s observed choice. As it is assumed that a rational consumer prefers more of both the goods to less of them or prefers more of at least one good, the amount of the other good remaining the same, we can infer that all combinations lying in the rectangular shaded area drawn above and to the right of chosen combination A are superior to A.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since in the rectangular shaded area there lie those combinations (baskets) of two goods which contain either more of both the goods or at least more of one good, the amount of the other remaining the same, this means that the consumer would prefer all combinations in the rectangular shaded area to the chosen combination A. In other words, all combinations in the shaded area MAN are superior to the chosen combination A.

As seen above, all other combinations lying in the budget-space OPL are attainable or affordable but are rejected in favour of A and are therefore revealed to be inferior to it. It should be carefully noted that Samuelson’s revealed preference theory is based upon the strong form of preference hypothesis.

In other words, in revealed preference theory, strong- ordering preference hypothesis has been applied. Strong ordering implies that there is definite ordering of various combinations in consumer’s scale of preferences and therefore the choice of a combination by a consumer reveals his definite preference for that over all other alternatives open to him.

Thus, under strong ordering, relation of indifference between various alternative combinations is ruled out. When in Fig. 12.1a consumer chooses a combination A out of various alternative combinations open to him, it means he has a definite preference for A over all others; the possibility of the chosen combination A being indifferent to any other possible combination is ruled out by strong ordering hypothesis.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

J. R. Hicks in his “A Revision of Demand Theory’ does not consider the assumption of strong ordering as satisfactory and instead employs weak ordering hypothesis. Under weak ordering hypothesis (with an additional assumption that the consumer will always prefer a larger amount of a good to a smaller amount of it), the chosen combination A is preferred over all positions that lie within the triangle OPL and further that the chosen position A will be either preferred to or indifferent to the other positions on the price-income line PL.

“The difference between the consequences of strong and weak ordering, so interpreted amounts to no more than this that under strong ordering the chosen position is shown to be preferred to all other positions in and on the triangle, while under weak ordering it is preferred to all positions within the triangle, but may be indifferent to other positions on the same boundary as itself.”

The revealed preference theory rests upon a basic assumption which has been called the ‘consistency postulate’. In fact, the consistency postulate is implied in the strong ordering hypothesis. The consistency postulate can be stated thus: ‘no two observations of choice behaviour are made which provide conflicting evidence to the individual’s preference.”

In other words, consistency postulate asserts that if an individual chooses A rather than B in one particular instance, then he cannot choose B rather than A in any other instance when both are available to the consumer. If he chooses A rather than B in one instance and chooses B rather than A in another when A and B are present in both the instances, then he is not behaving consistently.

Thus, consistency postulate requires that if once A is revealed to be preferred to B by an individual, then B cannot be revealed to be preferred to A by him at any other time when A and B are present in both the cases. Since comparison here is between the two situations consistency involved in this has been called ‘ two term consistency by J.R. Hicks.

Weak Axiom of Revealed Preference (WARP):

If a person chooses combination A rather than combination B which he could purchase with the given budget constraint, then it cannot happen that he would choose (i.e. prefer) B over A in some other situation in which he could have bought A if he so wished. This means his choices or preferences must be consistent.

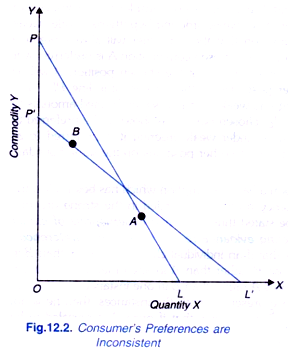

This is called revealed preference axiom. We illustrate, revealed preference axiom in Figure 12.2. Suppose with the given prices of two goods X and Y and given his money income to spend on the two goods, PL is the budget line facing a consumer. In this budgetary situation PL, the consumer chooses A when he could have purchased B (note that combination B would have even cost him less than A). Thus, his choice of A over B means he prefers the combination A to the combination B of the two goods.

Now suppose that price of good X falls, and with some income and price adjustments, budget line changes to P’L’. Budget line P’L’ is flatter than PL reflecting relatively lower price of X as compared to the budget line PL. With this new budget line P ‘U, if the consumer chooses combination B when he can purchase the combination A (as A lies below the budget line P’L’ in Fig. 12.2), then the consumer will be inconsistent in his preferences, that is, he will be violating the axiom of revealed preference.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such inconsistent consumer’s behaviour is ruled out in revealed preference theory based on strong ordering. This axiom of revealed preference according to which consumer’s choices are consistent is also called ‘ Weak Axiom of Revealed Preference or simply WARP. To sum up, according to the weak axiom of revealed preference.

“If combination A is directly revealed preferred to another combination B, then in any other situation, the combination B cannot be revealed preferred to combination A by the consumer when combination A is also affordable”.

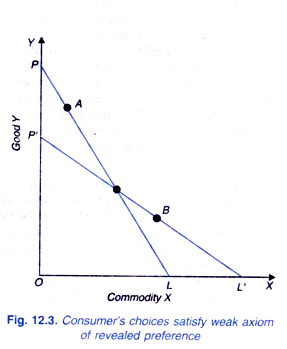

Now consider Figure 12.3 where to start with a consumer is facing budget line PL where he chooses combination A of two goods X and Y. Thus, consumer prefers combination A to all other combinations within and on the triangle OPL. Now suppose that budget constraint changes to P ‘L’ and consumer purchases combination B on it.

As combination B lies outside the budget line PL it was not affordable when combination A was chosen. Therefore, choice of combination B with the budget line P ‘L’ is consistent with his earlier choice A with the budget constraint PL and is in accordance with the weak axiom of revealed preference.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Transitivity Assumption of Revealed Preference:

The axiom of revealed preference described above provides us a consistency condition that must be satisfied by a rational consumer who makes an optimum choice. Apart from the axiom of revealed preference, revealed preference theory also assumes that revealed preferences are transitive.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to this, if an optimising consumer prefers combination A to combination B of the goods and combination B to combination C of the goods, then he will also prefer combination A to combination C of the goods. To put it briefly, assumption of transitivity of preferences requires that if A> B and B> C, then A > C.

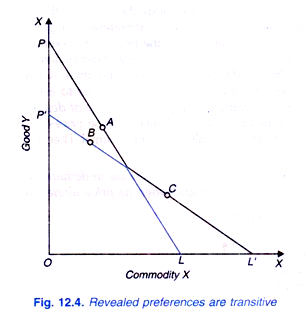

In this way we say that combination A is indirectly revealed to be preferred to combination C. Thus, if a combination A is either directly or indirectly revealed preferred to another combination we say that combination A is revealed to be preferred to the other combination. Consider Figure 12.4 where with budget constraint PL, the consumer chooses A and therefore reveals his preference for A over combination B which he could have purchased as combination B is affordable in budget constraint PL.

Now suppose budget constraint facing the consumer changes to P’L’, he chooses B when he could have purchased C. Thus, the consumer prefers B to C. From the transitivity assumption it follows that the consumer will prefer combination A to combination C. Thus, combination A is indirectly revealed to be preferred to combination C. We therefore conclude that the consumer prefers A either directly or indirectly to all those combinations of the two goods lying in the shaded regions in Figure 12.4.

It is thus evident from above that concept of revealed preference is a very significant and powerful tool which provides a lot of information about consumer’s preferences who behave in an optimising and consistent manner. By merely looking at the consumer’s choices in different price-income situations we can get a lot of information about consumer’s preferences.

It may be noted that the consistency postulate of revealed preference theory is the counterpart of the utility maximisation assumption in both Marshallian utility theory and Hicks- Allen indifference curve theory. The assumption that the consumer maximises utility or satisfaction is known as rationality assumption. It has been said that a rational consumer will try to maximise utility or satisfaction.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Recently, some economists have challenged this assumption. They assert that consumers in actual practice do not maximise utility. The revealed theory has the advantage that its rationality assumption can be easily realised in actual practice. The rationality on the part of the consumer in revealed preference theory only requires that he should behave in a ‘consistent’ manner.

Consistency of choice is a less restrictive assumption than the utility maximisation assumption. This is one of the improvements of Samuelson’s theory over the Marshallian cardinal utility and Hicks-Allen indifference curve theories of demand.

It is important to note that Samuelson’s revealed preference is not a statistical concept. If it were a statistical concept, then the preference of an individual for a combination A would have been inferred from giving him opportunity to exercise his choice several times in the same circumstances.

If the individual from among the various alternative combinations open to him chooses a particular combination more frequently than any other, only then the individual’s preference for A would have been statistically revealed. But in Samuelson’s revealed preference theory preference is said to be revealed from a single act of choice.

It is obvious that no single act of choice on the part of the consumer can prove his indifference between the two situations. Unless the individual is given the chance to exercise his choice several times in the given circumstances, he has no way of revealing his indifference between various combinations.

Thus, because Samuelson infers preference from a single act of choice the relation of indifference is inadmissible to his theory. Therefore, the rejection of indifference relation by Samuelson follows from his methodology. “The rejection of indifference in Samuelson theory is, therefore, not a matter of convenience but dictated by the requirements of his methodology.”