There is, as always, another side to the coin. As many scientists have pointed out development in technology has led to the saving of the environment in many ways. Ridley (2002) writes “the invention of new technology is not necessarily a threat to the environment; rather it is usually the best hope of environmental improvement”.

This claim may seem far-fetched but is important to understand and evaluate the facts before any conclusions may be drawn. Ridley himself recognises the need for hard facts and supplies statistics in favour of his view.

According to him, negative ideas spread more rapidly and attract more attention than positive ideas. Therefore, while numerous reports on the destruction of the earth and depletion of resources appear frequently in magazines and newspapers, very few reports focus on the actual scenario and the improvement that has taken place in the ecological system over the past decades. Citing the threat of acid rain as an example, Ridley writes.

By 1986, the UN reported that 23% of all trees in Europe were moderately or severely damaged by acid rain. What happened? They recovered. The biomass stock of European forests actually increased during the 1980s. The damage all but disappeared. Forests did not decline; they thrived.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Ridley the fact that the developed countries respond better to environment policy than the less developed countries in itself emphasis the need for development. He says that the less developed countries should be allowed to grow.

This would help them handle the basic problems like poverty, health care, etc., this in turn would help them to pay more attention to the environmental problems. The positive effects of development on the world may be grouped under certain broad categories.

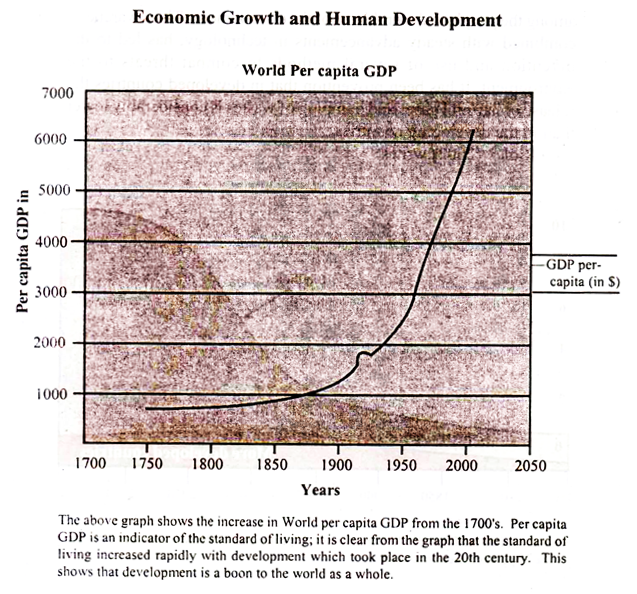

Economic growth is an important factor in reducing poverty and generating the resources necessary for human development and environmental protection. There is a strong correlation between gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and indicators of development such as life expectancy, infant mortality, adult literacy, political and civil rights and some indicators of environmental quality.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The world economy has grown approximately fivefold since 1950. This overall picture masks large, growing disparities among the developing countries not all countries have been able to take advantage of the benefits of globalisation (“Economic Growth”). Despite this, human development has led to the creation of awareness among the people to the problems of the environment.

This awareness, combined with steady advancements in technology, has led to the invention and use of several methods to combat threats to the environment. It has been prevention that in developed countries the release of harmful gases and dumping of wastes is considerably lower than in the developing countries.

Ridley (2002) writes:

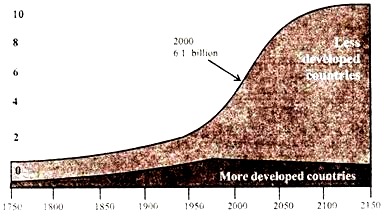

The above graph shows growth of the total world population over the last 2.5 centuries and predicts population for the next 1.5 centuries. From the graph it is clear that there was a boom in the population since the early 1900s.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is basically due to the tremendous development that took place during and after this period. In a span of fifty years (from 1950 to 2000) the world population tripled from 2 billion to a staggering 6.1 billion. At the present rate the world population is expected to touch 100 billion by the 2050.

The Italian academic Cesare Marchetti has produced a wonderful graph, which shows how humanity’s source of primary power has gradually shifted from wood to coal to oil to gas during the last century and a half.

Each of these fuels is successively richer in hydrogen and poorer in carbon than its predecessor, so we seem to be moving towards using pure hydrogen. Presumably, we will be making it from-water or natural gas with some kind of cheap electricity perhaps from nuclear power.

Suggesting that “by far the most powerful influence of how we treat our environment is not how much we care, nor how much we pass laws, but what technology we invent”, he concludes that it was development and “technical fixes that [actually] saved the whales, the woods and the wild game before”.

Education:

Well-educated, healthy populations are of fundamental importance in raising levels of socio-economic development. Numerous studies now document the positive correlations among, for example, women’s education, reduced fertility, and improved child health, and also between literacy rates and average per capita incomes.

Good education and health do not follow as an automatic consequence of economic growth but depend on government action, especially policies that target primary-level education and health care. The provision of high-quality basic social services benefits the poorer members of society, who cannot afford private alternatives, as well as the economy as a whole.

One multi-country study has indicated that a 10-per cent increase in life expectancy raises the national economic growth rate by about 1 per cent per year. Other research suggest that increasing the average education of the labour force by 1 year raises the GDP by 9 per cent, although this holds true only for the first 3 years of extra education, with diminishing returns thereafter.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Population:

For the last 50 years, world population multiplied more rapidly than ever before and more rapidly than it will ever grow in the future. World population expanded to about 300 million by A.D. 1 and continued to grow at a moderate rate. But after the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, living standards rose and widespread famines and epidemics diminished in some regions. Population growth accelerated.

World population growth accelerated after World War II, when the population of less developed countries began to increase dramatically. After millions of years of extremely slow growth, the human population indeed grew explosively, doubling again and again; a billion people were added between 1960 and 1975; another billion were added between 1975 and 1987.

Throughout the 20th century each additional billion has been achieved in a shorter period of time. Human population entered the 20th century with 1.6 billion people and left the century with 6.1 billion (“Human population”).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The growth of the last 200 years appears explosive on the historical timeline. The overall effects of this growth on living standards, resource use and the environment will continue to change the world landscape long after.

Fertility Rates:

The most rapid fertility declines have so far occurred in countries that have achieved major improvements in child survival rates and educational levels and have implemented family planning programs (for example, Colombia and Kenya).

These developments, in turn, are often associated with economic growth and social changes including improved reproductive rights, rural-urban shifts, new family structures, and new employment patterns, especially changes in female labour force participation rates.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Demographic Transition:

Demographic experts believe that the shift from high to low birth rates, and from low to high life expectancy, is brought about by “social modernisation.”

This complex of changes involves improved health care and access to family planning; higher educational attainment, especially among women; economic growth and rising per capita income levels; and urbanisation and growing employment opportunities.

Stabilisation of the world’s population will therefore depend on continuing or accelerating socio-economic development in the great majority of the world’s developing countries.

A number of factors could impede the demographic transition, including stagnating economic growth, persistent poverty, or cultural factors that encourage large family size despite rising prosperity. If the transition is stalled, global population would presumably continue to rise throughout the next century.

Growth of population may be viewed as harmful to the environment. Ridley (2001) writes of this popular misconception that:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In 37 years, India, for example, doubled its population, more than doubled its food production, but increased its cultivated land acreage by only five per cent. Its area devoted to woodland expanded by more than 20%. The tiger survived – thanks entirely to the intensification of agriculture.

This is one example that proves that, in reality, growth in population and the subsequent development of agriculture are positive signs as they indicate the sustenance of a species. This idea may be further developed under production.

Production:

Over most of history – including much of the 20th century – agricultural output has been increased mainly by bringing more land into production through conversion of forests and natural grasslands. The limits of geographic expansion were reached many years ago in densely populated parts of India, China, Java, Egypt, and Western Europe.

Intensification of production, obtaining more output from a given area of agricultural land, has thus become a growing necessity. In some regions, particularly in Asia, this has been achieved primarily through producing multiple crops each year in irrigated agro-ecosystems using new, short-duration crop varieties.

There has also been notable intensification of agricultural land use around major cities (and to an unexpected extent, within cities), particularly for high-value perishables such has dairy and vegetables, but also to meet subsistence needs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Over the past three decades, the per capita increase in production of the world’s three major cereal crops has been positive (up by 37% for maize, 20% for rice, and 15% for wheat) and prices in real terms for these crops have dropped (down by 43% for maize, 33% for rice, and 38% for wheat). Lowering the prices of major staples directly benefits the poor who spend a large part of their income on purchasing food.

The main reasons for these successes include:

1. A continuous flow of new production technologies such as improved seeds better management practices, and improved pest and disease control, all areas in which the CGIAR has been heavily involved;

2. The commercialisation of farming that has increased the availability and quality of production inputs and created more efficient means of marketing outputs, a direct result of good public policies; and

3. The expansion of international trade that has minimised price differences between locations and seasons, and fostered production patterns based on comparative advantage.

World food production has tripled since 1950, the price of food has dropped by nearly 50 per cent and the land used in agriculture has increased by nine per cent.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There are people who argue that increase in agriculture leads to destruction of forestland and upsetting of the environment but Ridley (2001) clearly states:

We have heard a lot recently about the supposed drawbacks of intensive agriculture. Like intensive power production, so intensive agriculture spares the landscape. There is no doubt that the green revolution helped us to produce vastly more food from every acre than we could have dreamed about two generations ago: hybrid seeds, inorganic fertilisers, pesticides, irrigation and mechanisation.

They are responsible for the failure of Lester Brown’s and Paul Ehrlich’s neo-Malthusian predictions. They have fed the world with more and more food at less and less cost. As a result modern farming is less land-hungry than its predecessors. Technology therefore leads to better conservation of the environment.