In the nineteen fifties and sixties there were among the development specialists the two major schools of thought regarding the strategy of economic development that should be adopted in developing countries. On the one side, there are economists like Ragnar Nurkse and Rosenstein Rodan who are of the view that the strategy of investment should be so designed as to ensure a balanced development of the various sectors of the economy. They, therefore, advocate simultaneous investment in a number of industries so that there is a balanced growth of different industries.

Economists, like H.W. Singer and A.O. Hirschman, on the other side, believe that for rapid economic growth there should be concentration of investment in certain strategic industries rather than an even distribution of investment among the various industries.

In other words, in the view of these latter economists, unbalanced growth is more conducive to economic development than a balanced one.

We may now consider both these views at some length.

Strategy of Balanced Growth:

Nurkse put forward the doctrine of balanced growth in order to break the vicious circle of poverty on the demand side of capital formation. It will be useful to have again a cursory look at this vicious circle.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In an underdeveloped country, the level of per capita income is low which means that the people’s purchasing power is low. Owing to small incomes and low purchasing power their demand for consumer goods is low. As a result of low demand for goods, the inducement for investment is less and capital equipment per capita (i.e., per worker) is small.

Since the amount of capital per capita is small, productivity per worker is low. Low per capita productivity means low per capita income, i.e., poverty. This completes the vicious circle of poverty. In a poor country, the size of the market for goods is small so that sufficient opportunities for profitable investment in industries are lacking. According to Nurkse, this is the main reason for lack of inducement to invest.

Size of Market and Inducement to Invest:

Investment means the expenditure on the making and installation of capital goods, e.g., construction of factories and the making of machines and their installation in industries. Obviously, an entrepreneur will be induced to invest in factories, machinery, etc., if he expects sufficient return on his investment. Businessmen invest only from a motive of earning a profit. It is the expectations of profits which is a fundamental factor influencing the amount of investment in a country at a given time. In a poor country, the low level of investment is due to low expectations of making profits because of less demand for goods or a small size of the market.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Let us understand clearly why there is less inducement to invest in a poor country. It is easily understandable that, in developing countries, there is great need for capital for economic development. Many people are too poor even to have two square meals a day or clothing to cover their bodies. Hence, there is an urgent need for large-scale production of consumer goods, but it cannot be done without the production and use of capital goods in large quantities.

The establishment and expansion of industries require investment. The need for capital can be great but the inducement to invest can be weak. The level of investment depends not on the need for capital but on the inducement to invest in the form of attraction to earn profit from the capital invested. Without reasonable expectations of making profits, much capital will not flow into investment.

The quantity of profitable investment in a country depends on the size of the market. Adam Smith said, “Division of labour is limited by the size of the market.” Nurkse says in the same manner that inducement to invest depends on the size of the market, that is, on the level of demand. The small size of the market or the low level of demand for the products concerned discourages the entrepreneurs from investment in industries.

This will be clear from an illustration. In a modern dairy, milking, filling up bottles and their loading all these operations are done with the aid of automatic machinery. Will the installation of such machinery in every small Indian town be profitable for individual entrepreneurs? Obviously, it will not be profitable. Per capita income being low in India, the demand for milk in each town will be too small to make the full use of such automatic machinery.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such costly plant and machinery will remain mostly idle and there will be work for such machinery only for a few hours during a week. This means a great waste of valuable capital asset. Which entrepreneur will dare start such a business? As an inducement to invest, the entrepreneurs should be sure that the capital equipment will be profitably employed. This will be possible only if the machinery can be kept in continuous use, and this cannot be done unless there is sufficient demand for the product made by this machinery.

Let us take another example. Suppose a cloth of a special design is very attractive and it can fetch a very high price. But it will not be economical to install a big machine to make a cloth of a special design, because owing to its high price and low incomes of the people, there will not be sufficient demand for this type of cloth, i.e., the market will be too small. In America, the cars are cheap but they are very expensive in India. What is the reason? The one reason is that the demand for cars in India as compared with that in America is so small that manufacturers of cars cannot be induced to make them in large quantities which would have made them cheap on account of the economies of scale. Examples can be multiplied. The conclusion is clear that inducement to invest depends on the size of the market or the purchasing power of the people.

It may be clearly understood that in the developing countries, according to Nurkse, demand for consumer goods cannot be increased merely by the expansion of money supply in the country. The real demand will increase only if there is increase in the productivity per worker and as a result thereof there is increase in the real per capita income. But mere expansion of money supply and thus putting more money into people’s pockets demand for goods increases which will result in inflation or higher prices, but not increase in the real effective demand and expansion in the capacity to produce goods.

Similarly, the demand for goods or the size of the market cannot be large merely because size of a country is big or its population is large. If the purchasing power of the people is low because of their extreme poverty, the demand for goods in that country will be small or the size of the market will be small even though the country is big in size or its population is large.

Mere more people without having purchasing power will not create real demand. Further, in poor countries, where the people’s purchasing power is low on account of low per capita income, the demand for goods, and hence the size of the market, cannot be increased by high pressure salesmanship and vigorous advertising campaigns. There should be enough people to buy them. Thus, it is clear that, in the underdeveloped countries, the demand for goods, or the size of the market, cannot be increased by increasing money supply, or by increase in population or by greater salesmanship and advertisement or the large size of the country. The size of the market can be increased only by increasing productivity. As Nurkse puts it, “The crucial determinant of the size of the market is productivity. Increase in productivity will increase people’s incomes and hence their purchasing power.

The level of people’s income in any country can be raised and consequently their purchasing power can be increased by increasing productivity and aggregate output or, in other words, by increasing productive employment. A situation of higher productivity, the greater employment and incomes and high purchasing power of the people will provide a profitable field for investment. It may be said that the size of the market can be enlarged by lowering the price of the products. But, according to Nurkse this is no solution of the problem. The real solution of the problem is only an increase in productivity of the people by raising productive employment. Only as a result of increase in productivity, there is increase in income and increase in purchasing power which will increase demand and enlarge the size of the market.

Say’s Law propounded by classical economists tells us that production or supply creates its own demand. But this law cannot be accepted in the sense that the production of cloth creates its own demand because the workers engaged in the making of cloth will not spend their entire earnings on the purchase of cloth. In the same way, production of shoes cannot create its own demand. The reason lies in the variety of man’s wants.

But, according to Nurkse, Say’s Law can be applied to the developing countries if investment is made simultaneously in a large number of industries in a way that incomes of a large number of workers engaged in these industries will increase. This will create demand for goods produced by one another. In other words, if investment is made simultaneously in a number of industries and production is increased, the supply will create its own demand. Say’s Law will hold well in such a situation.

Thus in Nurkse’s view, investment in a particular industry and the resultant production or supply cannot create its own demand but simultaneous investment in a number of industries can. As Nurkse puts it, “An increase in production over a wide range of consumables, so proportioned as to correspond with the pattern of consumer s preferences, does create its own demand.”

Nurksian Strategy of Balanced Growth:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We have explained above how, in the developing countries, the small size of the market or the limited demand for goods acts as a hindrance in the way of their economic growth or capital formation. When an entrepreneur wants to set up a factory or install plant and machinery, he makes sure whether there is enough demand for the goods he proposes to manufacture and whether the investment will be profitable.

We have seen above that owing to low demand for industrial goods investment is discouraged because of low profitability. That is why the vicious circle of poverty operates on the demand side of capital formation. The people in the developing countries are poor and their per capita income is low. This keeps the demand limited and size of the market small. Since the market is small, the entrepreneurs are discouraged from investment in plant and machinery in which only large-scale production is possible and economical.

The result is that capital formation in the country is discouraged. Nurkse points out that owing to lack of capital, productivity is low and since productivity per worker is low, the per capita income is low which means there is poverty. This is how the vicious circle of poverty operates in the developing countries. According to Nurkse, it is the vicious circle operating in the developing countries which stands in the way of their capital formation and economic development and, accordingly, if this vicious circle can be broken, capital accumulation will take place and economic development will follow.

The operation of the vicious circle can also be described thus- Inducement to invest depends ultimately upon demand, i.e., the size of the market. And the size of the market in turn depends upon productivity because the capacity to buy is ultimately based on the capacity to produce. Productivity, in its turn, largely depends on the use of capital. But, for an entrepreneur, the small size of the market will limit the use of capital so that productivity will remain low, thus keeping the size of the market small. The vicious circle will then repeat itself. This vicious circle of poverty, according to Nurkse, can be broken by a simultaneous investment in a large number of industries, i.e., by a balanced economic growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We have explained above how Say’s Law cannot be helpful in developing countries if investment is made only in one industry. The output of any single industry newly set up with capital equipment cannot create its own demand. Human wants being diverse, the people engaged in the new industry will not wish to spend all their income on their own product. Nurkse gives the example of shoe industry.

Suppose a shoe manufacturing industry is set up. If in the rest of the economy, nothing happens to increase productivity and employment, and hence the buying power of the people, the market for the additional output of shoes is likely to be deficient. People outside the shoe industry will not give up the consumption of essential food, clothing, etc., to create a sufficient demand for shoes every year. The supply of shoes is likely to outrun demand, and if investment is confined only to one particular industry, it cannot prove profitable.

But if investment is made simultaneously in a large number of industries, it will provide work for a large number of people producing diverse commodities. It will increase their income and they will be in a position to buy the consumer goods made by one another. This is how supply can create its own demand (as Say’s Law asserts) through the strategy of balanced growth. The workers employed in different industries become customers of one another’s goods and demand is increased or the size of the market is enlarged. The expansion of one industry helps in the expansion of others and there is all-round growth.

This is how the difficulty arising from small size of the market is overcome and the obstacle in the way of economic growth cleared. In Nurkse’s words, “The difficulty caused by the small size of the market relates to individual investment incentives in any single line of production taken by it. At least in principle, the difficulty vanishes in the case of different industries. Here is an escape from the deadlock; here the result is an overall enlargement of the market. People working with more and better tools in a number of complementary projects become each other’s customers. Most industries catering for mass consumption are complementary in the sense that they provide a market for, and thus support, each other. This basic complementarity stems in the last analysis from the diversity of human wants. The case for balanced growth rests on the need for a balanced diet.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Taken separately, a number of industries may be unprofitable so that the private profit motive would not suffice to induce investment in these industries. However, undertaken together in a synchronized manner, a balanced increase in production would enlarge the size of the market for each firm or industry so that “synchronized undertaking” would become profitable. This wave of capital investment in a number of different industries is called by Nurkse as “balanced growth.”

In this way, in Nurkse’s view, through balanced growth the hindrance to economic growth owing to the small size of the market is removed. The aggregate demand is increased as a result of simultaneous investment in a large number of industries, because the incomes go up and productivity levels of persons employed in different industries go up. Hence, the underdevelopment equilibrium trap and the vicious circle of poverty can be broken by balanced growth. If once this circle is broken, then, since there is circular connection, this circle will turn from poverty to balanced growth and to all-round development of the economy. In this way, the circle can be given beneficial form.

Now the question arises – Which industries should be selected for investment? The answer is to be found in the above solution offered by Nurkse. Investment should be made simultaneously in such industries the manufactured products of which are in accordance with the wants of the consumers, that is, on which the persons engaged in different industries would spend their incomes. There should be investment in a large number of complementary industries in the sense that persons employed in them become each other’s customers. Only by a simultaneous investment in such industries, production or supply will create its own demand.

Then the question is – How is it to be made sure that simultaneous investment in a large number of industries is actually made? Nurkse answers that, if in the country there are dynamic and constructive entrepreneurs and industrialists, they can be induced to make investment simultaneously in different industries. If there is lack of such entrepreneurs, then the government can’t take the work of balanced growth in its own hands. That is, the government can itself make simultaneous investment in several industries and can thus increase people’s incomes and productivity.

As a result of investment in several industries, it will be possible to increase the use of capital goods in large quantities which will raise the level of productivity and there will be a large increase in the aggregate output of consumer goods and services. As a result of this, the level of national income will rise which will help to raise the standards of living of the people. In this way, the poverty of the people will be eliminated. What is needed to remove the poverty of the people is to launch an attack on the various sectors of the economy simultaneously. This will remove the obstacle arising from limited demand or small size of the market. With this, inducement to invest will increase.

External Economies and Balanced Growth:

It will be proper to refer in this connection to external economies. When one industry creates demand for another, it will be profitable to the other industry. When one industry benefits from the growth of another industry, then we say that external economies are available from one industry to another. We have seen above that it proves profitable to make investment in complementary industries, because people engaged in such industries become one another’s customers or create demand for one another. It is clear, therefore that the doctrine of balanced growth is based on the concept of external economies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It should, however, noted that here we do not use the term ‘external economies’ in the sense in which Marshall used it. By ‘external economies’ Marshall meant those economies which arise from the localisation of a certain industry in a particular place and these economies are enjoyed by each firm in the industry by the establishment of numerous other firms there. But in development economics, by external economies we mean those benefits which accrue to the industries by the establishment of new other industries or the expansion of the other existing industries.

We have seen above how, according to Nurkse’s doctrine of balanced growth, these benefits accrue to the other industries by the establishment of other new industries or the expansion of old industries through simultaneous investment in such industries in the form of increased demand or extension of the market. In fact, the increasing returns which arise from the process of economic growth, are mainly due to the creation of external economies in the form of extension of the market or increase in demand and not due to the external economies mentioned by Marshall such as technical information from the journals, improvement in the technical skill of labour, development in the means of communication and transport, etc. which arise from the expansion of a particular industry in a particular place.

Nurkse has also not made clear in his doctrine of balanced growth whether investment should be made in capital goods industries and social overhead capital like transport and communications to promote balanced growth. Actually, Nurkse has suggested investment in consumer goods industries.

But how will the machinery and capital equipment required in these industries be obtained? If they are not to be imported from abroad, they will have to be produced in the country and for that purpose investment will have to be made in their production.

A Critique of Balanced Growth Doctrine:

Prof. Hans Singer and Albert Hirschman, eminent American economists, have criticized Nurkse’s doctrine of balanced growth. They contend that what is needed is not balanced growth, but a strategy of judiciously-planned unbalanced growth. According to Singer, balanced growth cannot solve the problem of the developing countries, nor do they have sufficient resources to achieve balanced growth.

Singer maintains that balanced growth doctrine might be better expressed as follows – “As hundred flowers may grow whereas a single flower would wither away for lack of nourishment.” But where are the resources to grow hundred flowers? Singer argues that the slogan “stop thinking piecemeal and start thinking big” is a sound advice for the poor developing countries but he also feels that there are “several areas of doubt” about the balanced growth theory in its Nurksian form.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

First, if the balanced growth doctrine is interpreted to advise the developing countries to embark on a large and varied package of industrial investment with no attention to agricultural productivity, it can lead to trouble. Balanced growth strategy of Nurkse, as of earlier ‘Big-Push Strategy’ of Rosenstein-Rodan underestimates the role of agriculture in economic development of developing countries. India in the Second and Third Five Year Plans followed Mahalanobis’ strategy of industrialisation with relative neglect of agriculture which led to shortage of food supply and balance of payments problems resulting in foreign exchange crisis.

Further, the big push in the form of simultaneous investment in a large number of industries requires a huge amount of resources/costs. At the initial stages of development, as the income grows with new industrial investment and employment, the relatively greater demand would be created for food and other agricultural goods. In order to sustain industrial investment, the agricultural productivity would have to be greatly raised. Thus, the big push in the industries must be accompanied by a big push in agriculture as well, if the country is not to run short of foodstuffs and agricultural raw materials during the transition to an industrialised society.

But serious doubts arise about the saving capacity of developing countries to follow the balanced growth path. According to Marcus Fleming, “Whereas the balanced growth doctrine assumes that the relationship between industries is for the most part complementary, the limitation of factor supply assures that the relationship is for the most part competitive.” Singer adds – “The resources required for carrying out the policy of balanced growth are of such an order of magnitude that a country disposing of such resources would in fact not be underdeveloped.”

Further, Furtado (1954) has made an important point that investment in large-scale industrial sector as envisaged in Nurksian balanced growth strategy is associated with capital-intensive production technologies used in the advanced industrialised countries. According to him, there are more labour-intensive technologies which are viable for production in small-scale industries and are not constrained by small size of the market or lack of demand for their products.

In fact, the balanced growth doctrine, like the big-push strategy, took for granted the appropriateness of capital-intensive production techniques. In so doing they underplayed the lower rate of saving and lack of adequate financial resources and other factors of production in the developing countries. Further, as has been pointed out by Fleming that if a particular factor is in short supply, expansion of one industry far from creating external economies to the benefit of other industries is likely to push up the price of that factor and thereby creating external diseconomies to the disadvantage of other industries.

Investment may be of whatever type, it necessarily induces some additional investment and some other productive activities. According to Singer, the expansion of social overhead capital and the growth of consumer goods industries and improvement of production techniques in them to raise productivity cannot take place simultaneously, because the developing countries have only limited capabilities of making use of their resources. In the developing countries, not only are the resources and the capabilities to bring about balanced growth lacking but, according to Hirschman, balanced growth is not even desirable.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

His view is that if economic growth is to be accelerated, it will have to brought about by unbalanced growth. If we promote growth by creating imbalances in the economy, the growth will be accelerated, because it will produce such incentives and pressures which will encourage overall development in the private sector. “The balanced growth doctrine is premature rather than wrong.” Singer concludes, “It is applicable to a subsequent stage of self- sustained growth rather than to the breaking of a deadlock.” For launching growth “it may well be a better development strategy to concentrate available resources on those types of investment which help to make the economic system more elastic, more capable of expansion under the stimulus of expanded market and expanding demand”. He mentions investments in social overhead capital and removal of special bottlenecks as examples of such “strategic” investment.

The fundamental trouble with the balanced growth doctrine, according to Singer, is its failure to come to grips with the true problem of developing countries, the shortage of resources. “Think Big” is a sound advice to underdeveloped countries, but “Act Big” is unwise counsel; if it spurs them to attempt more than their resources permit. Moreover, the balanced growth doctrine assumes that a developing country starts from scratch. In reality, every developing country starts from a position that reflects previous investment and previous development. Thus, at any point of time, there are some highly desirable investment programmes which are not in themselves balanced investment packages but which represent unbalanced investment to complement the existing imbalances.

There is another great lacuna in Nurkse’s balanced growth doctrine. Nurkse considers investment in only final consumer goods industries. But these final goods industries require capital goods such as machinery and other equipment. How will these capital goods required by final industries for their production would be obtained if they are not to be imported from abroad? They will have to be produced in the country and for them adequate investment will have to be made which will require more resources for investment.

Besides, the expansion of production in final industries also require social overhead capital such as power, steel, transport and communication to foster balanced growth. Nurkse did not show adequate recognition of interrelationship of industries from the supply-side viewpoint. The industrial growth is constrained both by the demand and supply-side factors. In the initial stages of industrialisation, tackling supply-side constraints is more important and relevant than the demand side.

As regards demand for industrial goods acting as a constraint, Paul Streeten rightly writers, “In so far as balanced growth is concerned, with the creation of markets through complementary investment projects and the inducement to invest by providing complementary markets for final goods, it stresses a problem which is rarely serious in the countries of the region. Final markets can often quite easily be created without recourse to balanced growth by import restrictions and less easily by export expansion.”

Another weakness of balanced growth argument, as pointed out by Hirschman, is lack of recognition by Nurkse that industries have both backward and forward linkages. Because of the limited availability of resources investment in those industries is given higher priority which has maximum linkage effects. The industries with maximum linkage effects are the leading sectors which ought to be given higher priority in order to ensure smooth and sustained growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

What remains of the doctrine of balanced growth is its emphasis on complementarity of final goods as they create demand for each other’s products. Besides, the importance of balanced growth lies in the fact that it brings out that level of demand may act as a constraint for industrial growth of the economy India’s growth experience shows that industrial deceleration during 1965-66 to 1978-79 was primarily caused by lack of demand caused by decline in public sector investment and exhaustion of possibilities of further import substitution.

Hirschman’s Strategy of Unbalanced Growth

Professor Albert Hirschman in his book, “Strategy of Economic Development,” carried Singer’s idea further and contended that deliberate unbalancing of an economy, in accordance with a predetermined strategy, was the best way of achieving rapid economic growth.

Like Singer, he argues that balanced growth theory require huge amounts of precisely those abilities which have been identified as likely to be very limited in supply in the poor developing countries.

He characterises the balanced growth doctrine as “the application to underdevelopment of a therapy originally devised for an underemployment situation” by J.M. Keynes. In an advanced country, during depression, “industries, machines, managers and workers as well as the consumption habits” are all present, while in poor developing countries this obviously not so.

As a developing country is incapable of financing and managing simultaneously a balanced “investment package” in industry and the needed investment in agriculture, in order to give a big push to lift an underdeveloped economy from a position of stagnation, Hrishman prescribes big push in strategic selected industries or sectors of the economy.

After all, he points out, the industrialised countries did not get to where they are now through “balanced growth”. True, if you compare the economy of the United States in 1950 with the situation in 1850, you will find that many things have grown, but not everything grew at the same rate through the whole century.

Development has proceeded “with growth being communicated from the leading sectors of the economy to the followers, one from industry to another; from one firm to another.”

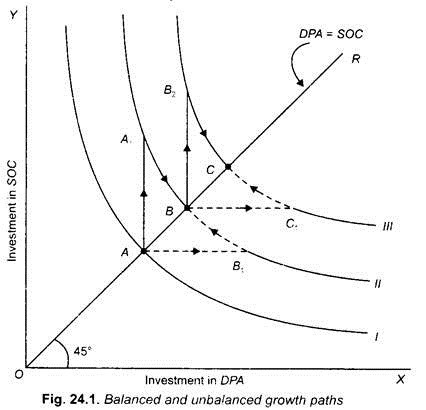

According to Hirschman, the sequence of development which is vigorously self-propelling should be adopted. We may explain the rationale behind this contention with the help of Hirschman’s diagram as shown in Fig. 24.1. In this diagram, the units of investment in SOC are measured along the vertical axis, while the unit of investment in DPA is measured along the horizontal axis. Now, should we choose ‘development via excess capacity of SOC or ‘development via shortage of SOC?

The curves, I, II, III are the isoquants, reflecting the different combinations of SOC and DPA that result in the same gross national products at a given time. As we move successively from curve I to II to III, we reach a higher level of gross national product. For the sake of analytical simplicity, the curves have been drawn in such a way that their optimal points lie on the 45° line.

In fact, this line gives the locus of balanced growth of DPA and SOC. Assuming that balanced growth of SOC and DPA is not possible because of the inherent limited ability of the poor developing countries to utilise resources, we have to determine that sequence of development which maximises induced decision-making.

Let us first consider the sequence of development via excess capacity of SOC. The path of development assumed by the economy would then be given by the heavy lines A → A1→ B →B2 → C. Starting from A, the increase in SOC to A1 invites increase in DPA till the balance is achieved at B. With the increased gross national product, the government may undertake further investment in SOC to B2. This in turn will induce the DPA to increase to the point C.

If, on the other hand, the economy adopts the sequence of development via shortage of SOC, the course followed by the economy would be the one shown by the dotted lines AB1BC1C. In this case to start with, we increase DPA from A to B1.To restore balance; this will be followed by the increase in SOC from B1 to B. If there is a further increase in DPA to C1.SOC will have to follow suit until balance is restored at C.

It needs to be noted that unbalanced growth via both the paths yields an “extra dividend” of “induced easy-to-take or compelled decisions resulting in additional investment and output”. However, the sequence of development via excess capacity of SOC is what Hirschman calls “self- propelling” in the sense that it is more continuous and smooth. The second path, i.e., ‘development via shortage of SOC, lacks this attribute since it may take some time for the political pressure to be generated so that the adjustment in SOC is delayed. And thus the DPA cost of producing an amount of output is pushed up. In Hirschman’s terminology, the ‘development via excess SOC is basically a permissive sequence, while the development via shortage of SOC is essentially a compulsive sequence.’

Having demonstrated the virtues of strategic imbalances, we are left with the problem of discovering what kind of imbalance is likely to be most effective. Any particular investment project may have both “forward linkage” (that is, it may encourage investment in subsequent stages of production) and “backward linkage” (that is, it may encourage investment in earlier stages of production). The task is to find the projects with maximum “total linkage.” The projects, with the maximum total linkage, will vary from country to country and from time to time and can be discovered only by empirical studies of the “input-output tables”.

In determining the sequence of projects, planning authorities should also give attention to the alteration of “pressure-creating” and “pressure-relieving” investment. In countries with vigorously expanding private enterprise sectors, the government’s function can be largely limited to “pressure- relieving.” As private investment takes place, shortages and bottlenecks will appear in transport, public utilities, education, and other activities traditionally assigned (in whole or in part) to public enterprises in such societies. Government ought not to feel “restless and slighted” when confined” to this “induced role.”

Where expansion through private investment is not assured, the government’s role must be more active. For example, it might build an iron and steel industry. “It is interesting to note,” says Hirschman. “that the industry with the highest combined linkage score is iron and steel. Perhaps the underdeveloped countries are not foolish and exclusively prestige-motivated in attributing prime importance to this industry, because of the high total linkage effects of iron and steel industry.”

The building of it by the government will lead to a spurt of investment and production in a variety of fields both in the stages before and after this industry. In this way, it accelerates economic growth. The investment in iron and steel industry will reveal deficiencies in the preceding and succeeding sectors of industry that the government must fill up. To remove these deficiencies and obstacles, further investment will be stimulated. When these deficiencies are filled up, further private investment will take place, and so the process of growth goes on.

The foregoing discussion leads us to the conclusion that according to Hirschman, the balanced growth doctrine is neither attainable nor desirable. On the other hand, for rapid economic development the developing countries should rely largely on judiciously-planned unbalanced growth. In fact, under the Mahalanobis strategy of development, India followed this course.

A Critique of Unbalanced Growth Strategy:

The strategy of unbalanced growth has come in for severe criticism. First, it has been pointed out that unbalanced growth strategy is based on wrong assumption that only factor constraining economic growth is the scarcity of decision-making ability in respect of investment. According to it, all that is needed for accelerating growth in less developed countries is to provide inducements and incentives to private enterprise to undertake investment projects.

Once this is done, supply of financial resources will adequately flow into investment projects. This is not a realistic assumption to make in the context of the developing economies. In the developing countries supply of financial resources is scarce due to low rate of saving and this hampers economic growth. Hirschman paid little attention to overcome this bottleneck to accelerate growth. Thus, not only the supply of physical resources are limited but also the availability of financial resources for funding the developmental projects is scarce.

Hirschman’s unbalanced growth strategy has also been criticised on the ground that it will generate inflationary pressures in the economy. Whether more investment is undertaken in social overhead capital (SOC) or directly productive activities (DPO) incomes of the people will rise which will lead to the increased demand for consumer goods, especially food-grains. If sufficient investment in agriculture and other consumer goods industries is not made, it will cause rise in prices as was actually witnessed in India during the Second and Third Five Year Plans.

Thirdly, it has been pointed out that in case response from private enterprises to the inducements and pressure created by unbalanced growth strategy is not adequate, imbalances will be created in the economy without causing expansion in the other linked sectors resulting in excess capacity in some industries or sectors. This excess capacity represents waste of resources.

Lastly, it has been pointed out by Paul Streeten that unbalanced growth strategy neglects the possibility of resistances for adjustment to imbalances created by the unbalanced growth strategy. These resistances to growth may occur in a variety of forms. There may come into existence monopolies which have vested interests in restricting expansion in output. In the background of imbalances and shortages private enterprises which are interested in making quick profits will be more willing to raise prices of products rather than expanding their quantities. As Paul Streeten emphasizes – “The theory of unbalanced growth concentrates on stimuli to expansion and tends to neglect or minimise resistances caused by unbalanced growth.”

We however conclude that despite some shortcomings in the unbalanced growth strategy, laying stress on the decision-making ability for accelerating economic growth and on the need for building up social overhead capital, Hirschman has made a valuable contribution to development economics.

An important weakness of Hirschman’s doctrine of unbalanced growth, like that of Nurkse’s balanced growth approach is that be does not consider the role of supply limitations. Hirschman lays stress on decision-making for accelerating investment. He thinks that supplies of inputs and physical resources will be forthcoming with relative ease once lack of decision to undertake investment or expand production can be tackled; Hirschman seems to think that supplies of resources are not a constraint and emphasises the scarcity of decision-making in developing countries.

Paul Streeten rightly writes, “The contrast drawn by unbalanced growth doctrine between scarcity of resources and scarcity of decision-making can be misleading. Those who stress resources say that decisions will be taken as soon as resources are available; those who stress decision-making say that resource will flow freely as soon as adequate inducements to take decisions are provided”. While the former group of experts out on missions advocate high taxation in order to “set resources free”, the latter recommends low taxation in order to “encourage enterprise.”

Another important shortcoming of Hirschman’s unbalanced growth doctrine, like Nurkse’s balanced growth doctrine, is that planning is required to implement his strategy. In unbalanced growth strategy planning is required “as much at restricting supplies in certain directions as at expanding them in others. The policy package presupposes a choice of allocating limited supplies and in response to certain stimuli the most important uses combined with inducements to make decisions of all kinds (not only investment decisions).”

Hirschman has underestimated the difficulties and problems faced in the implementation of unbalanced growth. All investments create imbalances because of rigidities, indivisibilities, sluggishness of response both of supply and of demand and because of miscalculations. Free working of market will be unable to overcome these difficulties. These problems can only be solved if economic planning is adopted to coordinate and make required adjustments so that smooth and steady growth is possible.

In the words of Paul Streeten, “There will be, in any case, plenty of difficulties in meeting many urgent requirements whether of workers, technicians, managers, machines, semi-manufactured products, raw materials or power and transport facilities and in finding markets permitting full utilization of equipment. Market forces will be too weak or powerless to bring about required adjustments and unless coordinated planning of much more than investment is called out, the investment projects will turn out to be wasteful and will be abandoned.”

Although Hirschman’s unbalanced growth doctrine is not without flaws, his emphasis on ability to take decision and the need for incentives for investment if economic growth is to be accelerated. He rightly lays stress on right attitudes and institutions for bringing about economic growth. More importantly, Hirschman’s analysis of backward and forward linkages is an important contribution to the theory of economic development.