We shall explain below Joan Robinson’s model of capital accumulation and growth which is suited to the labour-surplus conditions of less developed countries.

Harrod and Domar extended the Keynesian analysis of income and employment to the long-run setting and therefore considered both the income and capacity effects of investment. Harrod and Domar models of economic growth explain at what rate investment should increase so that steady growth is possible in an advanced capitalist economy. In the growth models of Harrod and Domar, the rate of capital accumulation plays a crucial role in the determination of economic growth.

Joan Robinson has further refined the model of capital accumulation in a private enterprise economy. She relates investment with the rate of profit which in turn depends upon the distribution of income between wages and profits on the one hand and labour productivity and capital intensity on the other.

Assumptions of Joan Robinson’s Model of Growth:

In Joan Robinson’s model of economic growth and capital accumulation the following assumptions are made:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) It is assumed that in a free private enterprise economy perfect competition prevails among producers and consumers of products. Further, the economy is a closed one, that is, it has no foreign trade with other countries.

(ii) There are only two factors of production, namely, labour and capital. Therefore, the entire national product is distributed among “entrepreneurs” and “workers”. The entrepreneurs get profits (income from property) and workers obtain wages (the income from work).

(iii) State of technology remains the same, that is, no technological progress takes place.

(iv) Entrepreneurs save all their profits while workers spend all their wages on consumption and save nothing. Thus, it is only the entrepreneurs who do the savings and save all their profits.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(v) It is assumed that capital and labour are combined in a fixed proportion to produce a given level of output. In other words, technical coefficients of production are fixed.

(v) Labour is the surplus factor, and entrepreneurs employ as much labour as they find it profitable.

Joan Robinson’s Model – Output and Income Side of Capital Accumulation:

Given the above assumptions, the net national income of the economy will consist of the total wage bill and the total profits. As such, the distribution of net national income among the entrepreneurs and workers is given by–

pY= wN+ πpK …(1)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(National Income) = (Wage Bill + Profits)

Y = denotes net national output

N = denotes number of workers employed

K = denotes amount of capital stock used to produce the given national product Y

w = denotes money wage rate paid to the workers

π = denotes the gross rate of profit (inclusive of the interest rate)

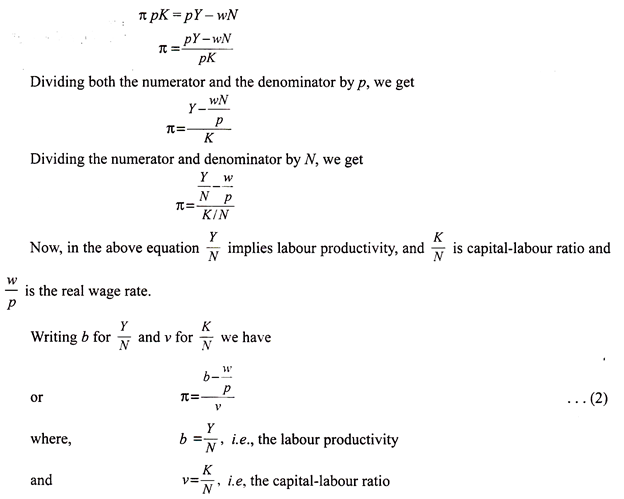

p = denotes the average price level of output, both of output and stock of capital goods From equation (1) above, we get–

The equation (2) shows that the profit rate is a function of the labour productivity b, real wage rate (w/p) and the capital-labour ratio (ν). For maximising profits, the entrepreneurs will operate on these variables in conformity with the equation (2). The profit rate can be increased either with the increase in the increase in the labour productivity b or with the decrease in the real wage rate (w/p) and decrease in the capital-labour ratio (ν). The equation (2) shows that given the labour productivity (b) and capital- labour ratio (ν), the rise in real wage rate (w/p) will reduce the profit rate and fall in the real wage rate will raise it.

Expenditure Side of Capital Accumulation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now, the expenditure side of the economy is represented by the familiar Keynesian equilibrium condition, namely, national income equals the sum of consumption expenditure (C) and investment expenditure (I). Thus–

Y= C + I….. (3)

When aggregate expenditure (C +I) equals aggregate output (i.e., Y), then intended saving must also be equal to intended investment (I). Therefore, at equilibrium level of national income –

S = I … (4)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Where, C, S and I have the usual meaning.

As explained above, Joan Robinson assumes that all profits made by entrepreneurs are saved and all wages earned by workers are consumed. Given this assumption–

S=πK….. (5)

All profits are, meant to be ploughed directly into investment. As such we can write the equation (4) in the following form–

ADVERTISEMENTS:

S = πK = I…… (6)

Writing ∆K (i.e., increase in the stock of real capital) for I in the above equation we have–

∆K = πK

Or π = ∆K / K

This means that, given the assumptions made, rate of profit (π) is equal to the rate of investment expressed as a ratio of change in capital to the total stock of capital (K).

Equilibrium Growth:

For getting the equilibrium, we simply have to juxtapose the income and expenditure sides expressed in (2) and (6) above respectively. Thus, the equilibrium condition is–

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This equilibrium condition manifests a double-side relationship between the rate of profit and rate of accumulation. On the one hand, it tells us that the rate of accumulation going on in a particular situation determines the level of profits obtainable therefrom. It also shows the rate of profit which the entrepreneurs would expect on their investment.

On the other hand, the equilibrium condition shows that the rate of profit itself governs the rate of accumulation. Anything that determines the rate of profit would also determine the rate of growth of capital. Thus in Joan Robinson’s model of growth the urge to accumulate capital on the part of entrepreneurs determines the rate of economic growth. And the urge or desire of the entrepreneurs to accumulate capital depends on the expected rate of profit.

Accumulation and profit are, therefore, linked with each other in a circular way. “If they have no profit, the entrepreneurs cannot accumulate and if they do not accumulate they have no profit”. Thus, the basic mechanism underlying Mrs. Robinson’s growth model is the desire of the firms to accumulate. And the urge to accumulate is dependent on the expected rate of profit.

Desired Rate of Accumulation:

In a manner very much akin to that of Harrod’s line of argument, Mrs. Robinson draws a distinction between the ‘desired rate’ of accumulation (analogous to ‘warranted rate’) and the ‘possible rate’ of accumulation (similar to ‘natural rate’).

The desired rate of accumulation is that rate of accumulation which generates just that expectation of profit which is necessary to cause it to be maintained. In other words, it is that rate of accumulation which would make the firms feel satisfied with the economic conjuncture in which they find themselves.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To be able to appreciate the significance of this concept, it is necessary to know the relation between “the rate of profit caused by the rate of accumulation and the rate of accumulation which that rate of profit will induce.” Mrs. Robinson makes use of the following diagram to bring out this distinction.

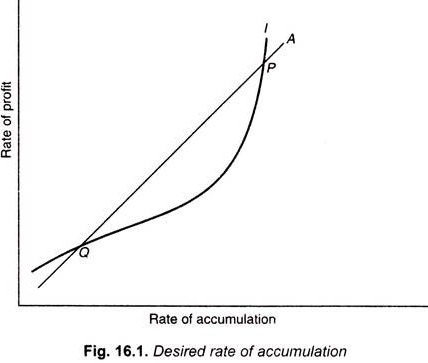

The curve A depicts the rate of profit as a function of the rate of accumulation that gives rise to it. On the other hand, the curve I shows the rate of accumulation as a function of the rate of profit that induces it. The two curves intersect at the point P and Q in fig 16.1.

When the firms operate in the region lying to the right of the point P, the rate of accumulation that takes place in the economy exceeds than what is justified by the rate of profit that it entails. Such a situation may arise when the ratio of plant and equipment as between the basic and commodity sectors is unduly high. So that any further investment in the former is unlikely to be profitable. In the immediate future, therefore, this ratio is likely to fall and consequently the rate of accumulation would also fall.

If, however, the rate of accumulation that is taking place at present happens to be lower than the rate of profit that it entails, a situation quite converse of the one described above will be faced. In terms of the figure, if the firms are operating in the region bounded by the points P and Q, they shall tend to step up the rate of accumulation. This is likely to happen when the ratio of machinery as between the capital goods and the consumer goods sectors happens to be low, so that a higher proportion of current investment will tend to flow to the capital goods sector. This would result in increasing the rate of accumulation.

The lower point of intersection of the curves I and A, i.e., the point Q, is indeed a crucial point. It is a point where the rate of accumulation is generating just that expectation of profit which is essential to cause it to be maintained. This is the ‘desired rate’ of accumulation. It is desired in the sense that the firms feel contented in the situation in which they find themselves. Evidently, the ‘desired rate’ of accumulation is quite analogous to Harrod’s ‘warranted rate’ of growth.

Possible Rate of Growth:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If the desired rate of accumulation continues unfailingly in the long nm without any disturbing influences, the economy will be said to develop under tranquil conditions. It is because under such conditions complete harmony in the growth process shall be achieved. The composition of the stock of productive capital will adjust completely in consonance with the requirements.

In particular, the distribution of plants and machinery as between the basic and the commodity sectors shall be most appropriate and in keeping with the desired rate of accumulation. All in all, there shall be a steady proportionate growth in the physical stock of various kinds of plants on the one hand, and the working capital on the other. In sum, the system shall be in a sort of internal equilibrium.

But the pertinent question is – shall such internal equilibrium exhibiting tranquil conditions continue to prevail uninterruptedly? The answer is that it depends! The unhindered continuance of the tranquil conditions is possible only if the desired rate of accumulation becomes so by virtue of the physical conditions of the economy. This leads us to the concept of ‘possible rate’ of growth, which is the counterpart of Harrod’s ‘natural rate’ of growth. The ‘possible rate’ of growth is that rate of growth which is made ‘possible’ by the physical conditions resulting from the growth of population and technical knowledge.

On the basis of the various possibilities arising out of the juxtaposition of the ‘desired’ and ‘possible; rates of growth, Mrs. Robinson makes distinction between alternative types of equilibrium growth paths. She designates the various equilibrium growth paths as ‘ages’.

Golden Ages:

The situation of smooth steady growth with full employment arising out of the equality of the ‘desired’ and ‘possible’ rates of accumulation has been designated by Mrs. Robinson as the ‘golden age’ equilibrium.

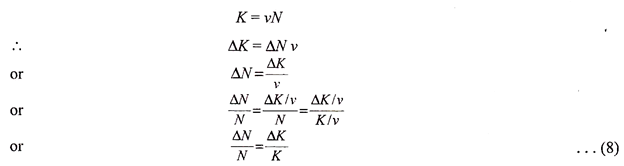

Assuming v to be constant under conditions of full employment, then from the equation K/N = ν, we get-

The equation (8) implies that if ν is constant at the full-employment level, then labour and capital grow at the same rate.

This is the situation of ‘golden age’ equilibrium. The equality between the desired and possible rates of accumulation coexists with full employment of labour and capital. Besides, both labour and capital grow at the same rate. The economy is thus on a tranquil steady growth path —”a steady rate of accumulation then rolls smoothly on its way.” There is harmony in all respects.

The entrepreneurs are in a state of equilibrium as their desired rate of accumulation is being realised. The wage-earners, on the other hand, are in an equilibrium state because there comes to prevail an overall harmony in the demand and supply of labour. In the Harrodian terminology, Mrs. Robinson’s ‘ Golden Age’ is that state of the economy where the ‘ warranted rate’ gets equated to the ‘natural rate’ and full employment is maintained throughout.

Stability of ‘Golden Age’ Equilibrium:

If certain forces operate so as to disturb the ‘golden age’ equilibrium of the economy, equilibrating mechanism automatically comes into being to restore the equilibrium. Let us see how?

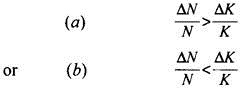

The divergence from the ‘golden age’ equilibrium path will take place if –

In the first case, when ∆N/N > ∆K/K the population will grow faster than the capital stock. This, therefore, signifies the situation of underemployment. With the prevalence of surplus labour, money wage rates get depressed. But if price level is to remain unchanged, the real wages will have to fall.

Now if real wages start falling, then as is clear from the basic equilibrium equation (vii), the rate of profit will rise gradually. As such, the rate of growth of capital accumulation will go on moving up till it catches up with the rate of growth of population. And the ‘golden age’ equilibrium would, thus, again be established. However, the equilibrium would fail to be restored if the money wages remain inflexible or if the price level falls in consonance with the fall in the money wages,

The second possibility for divergence from the ‘golden age’ equilibrium occurs when ∆N/N < ∆K/K i.e, the rate of population growth falls short of the growth rate of capital stock. Such a situation manifests a state of excess capital accumulation. It can be seen that under such circumstance, appropriate changes in the capital-labour ratio (ν) or the labour productivity (b) can help to regain the ‘golden age’ equilibrium. Another way is that the whole production function as such may be shifted up so that with the increase in capital accumulation, more and more labour gets absorbed in the production process. In any case, it is relatively easier to re-establish ‘golden age’ equilibrium when the divergence from that path stems from a slower growth of population than capital.

State of Economic Bliss:

This is a special case of ‘golden age’ equilibrium. When the rate of accumulation is zero, profit rate is also zero and the entire output of the industry is drained out in the wage-stream, the consumption would be at its highest pedestal. It could be possible, says Mrs. Robinson, to maintain consumption at such a maximal level under the given technical conditions. This then is the ‘state of economic bliss’.

Causes of Cyclical Fluctuations:

Let us now see as to how the emergence of cyclical fluctuations can be explained in Mrs. Robinson’s ‘golden age’ equilibrium framework. Mrs. Robinson asserts that fluctuations would disturb the conditions of tranquil growth in the ‘golden age,’ if there occur certain random shocks or chance events, viz., the occurrence of a bout of exceptionally attractive innovations or a sudden burst of consumer expenditure and/or things like that.

The manner in which the fluctuations get a pace and are maintained is explained below.

Any disturbance that pushes up the profit rate tends to raise the desired rate of accumulation. Consequent thereupon, the investment increases to prop up higher levels of accumulation new equipment gets installed. The result, therefore, is that the productive capacity of the economy moves ahead of the level of effective demand. This naturally leads to a decline in the profit expectations so that forces retarding fresh investments come into being. On the other hand, any chance disturbance that pushes down the profits tends to set in the downward movement.

Mrs. Robinson also mentions about a more radical type of cyclical instability that may sway the economy. When the expectations are influenced not only by the existing situation but also by the projection of the experiences of recent past, the system develops what is known as the ‘ inherent instability’. The experience of a rise in profits in the immediate past would give rise to expectations of a further rise. Conversely, the recent past experience of a fall in the profits would bring expectations of a further fall.

Mrs. Robinson feels that under such exigencies, it would be difficult for the firms to settle down on any one perch of steady rate of accumulation. When, for instance, the profit rate is ascending, the firms are prone to pitch their desired rate of accumulation at a high level. However, the moment this desired rate of accumulable gets realised, the profits stop rising any further. As such the desired rate would no longer continue to be the desired one. A new rate of accumulation at a lower level would then be the one that is desired.

Such fluctuations are thus the outcome of the volatility of expectations. All this entails uncertainty which continually makes the firms to adopt self-contradictory policies, f he net result is the emergence of an unsteady or disequilibrating rate of accumulation in relation to the desired rate. In consequence thereof, the path of growth also turns unstable. The point to be noted is that fluctuations of this type are endogenous to the system. They have not been generated by the entry of any random shock or chance event. What has happened in this case is that the system has become inherently unstable.

This part of Mrs. Robinson’s exposition enables us to discover a common source of growth and fluctuations. It is the fortuitous nature of expectations and enterprise in a system governed by profit that explains growth and fluctuations together. This aspect of Mrs. Robinson’s model is, therefore, particularly laudable in that it succeeds in coordinating the theories of cycles and growth.

Limping Golden Age:

Under this limping golden age, steady rate of accumulation coexists with unemployment. It is just possible that sufficient capital stock with a composition quite appropriate to the desired rate of accumulation exists. But it may not be that enough in so far as the employment of the entire labour force is concerned. The steady rate of accumulation is taking place, but the conditions of full employment have not been achieved. Mrs. Robinson christens such a state of affairs as the ‘limping golden age’.

The intensity of the limp may be of different degrees depending on the rate of fall or rise in employability vis-a-vis the labour force. If the rise in the level of employment occurs at a rate smaller than that of labour force, unemployment would increase with time. The limp in this case is rather severe.

However, if the rise in the level of employment occurs at a rate greater than that of labour force, employment would increase more rapidly than the labour force. And, therefore, unemployment will shrink with time and the economy approaches full employment rather quickly. The limp here is thus mild and it tends to die away in the long run. As such, this age will only be a transient one.

Leaden Age:

It is in fact, a special case of a ‘limping golden age’ in which the degree of unemployment is increasing due to inadequate rate of accumulation. When there are a large proportion of unemployed workers in the economy, the level of living of all the workers will get reduced. Unless the real wages of the employed workers rise fast enough or else sufficient opportunities for self-employment arise, conditions of falling standards of living will continue. But it is quite unlikely that any of these possibilities would occur in practice. Real wages do not rise fast enough nor do opportunities for self- employment crop up in large numbers.

The low rate of accumulation giving rise to the low standard of living may thus limit down the growth of numbers – a sort of Malthusian trap sets in. Assuming that there is no technical progress, a condition of ‘golden age’ may be forced upon the economy artificially. It is quite distinct from the true ‘golden age’ in that here a high ratio of non-employment keeps down the rate of growth of the labour force.

If the standards of living had not fallen, growth of labour force would not have slided down so that the inadequate rate of accumulation would have expressed itself in increasing degrees of unemployment. Thus, under the leaden age, the rate of growth of labour force has been as leaden as to decline under the weight of increased misery stemming from an insufficient rate of accumulation.

Restrained Golden Age:

This is an age of full employment but the ‘desired rate’ of accumulation happens to exceed the ‘possible rate’ determined by the rate of growth of labour force plus the rate of technological progress. The ‘possible rate’ is kept down by factors such as financial stringency or monopsony in the labour market, so that the’ realised rate’ of growth is kept down to the level of the ‘possible rate’.

It may so happen that the stock of capital is appropriate to the desired rate of accumulation and the full employment has already been achieved. But it may fail to be realised on account of its being restrained by a stinted rate of growth of labour force and the rate of technical progress.

Bastard Golden Age:

It denotes a situation where unemployment prevails but the real wages remain rigid downwards. As such, the rate of accumulation is prevented from increasing in the absence of technical progress. The ultimate cause of less than adequate growth of capital stock may lie in the existence of an ‘ inflation barrier’.

For the rate of accumulation to be raised, it is necessary to lower down the real wages. But generally there is some level of minimum acceptable real wages so that when prices rise, some increase in money wages follows due to the attempts of the organised labour to resist the erosion of real wages through inflation below the minimum acceptable level. Thus, the realisation of the desired rate of accumulation would tend to be choked off. The attempts to raise the rate of accumulation would be arrested by the inflationary rise in money wages. This is the ‘bastard golden age’.

Critical Appraisal of Robinson’s Model:

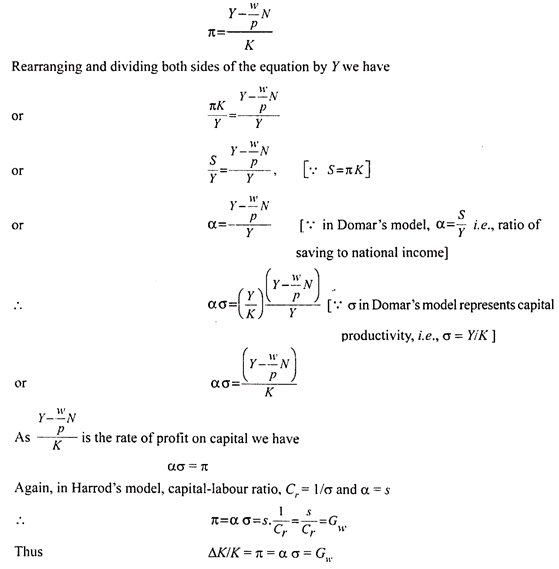

Mrs. Robinson’s model represents a major step in enriching our understanding of the fundamental nature and process of capital accumulation in a capitalist economy. It also provides deep insight into the properties of equilibrium growth. It is worth mentioning that in Mrs. Robinson’s model, all profits are saved and all wages are consumed. The Robinsonian model is essentially of the Harrod-Domar breed. This can be seen easily from the following relationships.

We have earlier shown that –

This shows that Mrs. Robinson’s equilibrium condition is the same as that of Domar’s stable rate of growth (α σ) or Harrod’s ‘warranted rate’ of growth (Gw). However, Mrs. Robinson’s model has an edge over the Harrod-Domar models in two respects. First, in the Harrod-Domar models, capital accumulation is determined by the saving-income ratio and the capital productivity.

But, Mrs. Robinson distinctly links capital accumulation with the profit-wage relation and the labour productivity. This marks a big step forward in that she has brought growth theory closer to a market economy. Secondly, while in the Harrod-Domar models, the prime-mobile of capital accumulation is capital itself, in Mrs. Robinson’s case, it is the labour. The latter is more realistic for labour is the ultimate source of all capital.

Synthesis between Value Theory and Distribution Theory:

The chief merit of Mrs. Robinson’s model lies in its successful synthesis of the classical value and distribution theory with the Keynesian saving-investment analysis into a single coherent stream of thought. The close connection between distribution and growth has been brought out exquisitely through the demonstration of mutual interdependence between the effect of income distribution and the proportion of income saved on the one hand, and between the rate of profit and capital accumulation on the other.

Problem of Measurement of Capital:

Further, great credit goes to Mrs. Robinson for bringing to the fore the much neglected problem of measurement and composition of capital. She out-rightly discards the dictum of homogeneity and malleability of capital stock. Her model demonstrates that a given set of machinery cannot by itself get adapted to more or less labour-intensive forms of production.

In other words, ex-post substitution is not possible. However, substitution is possible in the ex-ante sense, i.e., at the time when the choice of techniques is being made. Once the techniques are chosen and machines built, a particular technique gets permanently associated with them. The chosen technique is embodied in the machines and it will remain embodied throughout their lifetime. It is only in the long run when the existing machines get completely depreciated that they can be replaced by plants that embody a different technique.

Furthermore, the Robinsonian model provides a realistic meaning and significance of the ‘steady-state growth’ so as to analyze the various ingredients, properties and types of equilibrium growth process. The idea of steady growth had been haunting economists since long. Cassel was the first to visualise it as a generalisation of stationary state, i.e., a ‘regularly progressing state’ of the economy. Harrod introduced this concept in his comparative dynamic framework with a view to analyze the short-run instability implications arising from the divergence between the warranted and natural rates of growth. But it is not possible to employ the Harrodian concept of knife-edge equilibrium as a datum to compare different types of equilibrium growths.

Besides, Harrod’s steady growth does not take cognizance of the composition of the capital stock. As opposed to this, Mrs. Robinson’s ‘golden age’ idea embodies the compositional aspects of capital stock. Also, it provides us with a device for comparing different types of equilibrium-growth paths. It plays the same role in comparative dynamic analysis as does the concept of stationary state in a comparative static setting. As such, Mrs. Robinson has perfected the analysis of comparative dynamics.

Above all, Mrs. Robinson’s model has the merit of coordinating the theories of cycle and growth. While elucidating the idea of ‘inherent instability’ in the system, she successfully forges and organic link between fluctuations and growth. From her model one could say that the inherent tendency to oscillate is the cause and unsteady growth is the outcome.

Shortcomings of Robinson’s Growth Model:

However, Mrs. Robinson’s model is not free from flaws. Some of the main drawbacks are as follows- First, Mrs. Robinson’s model at best provides only a framework for studying the various forms of growth process. It cannot be used as a predictive model. If the economy is passing through a particular type of Robinsonian growth, we cannot predict on the basis of the model as to what possibly shall be the succeeding phase or type of growth. The different types of growth that have been analyzed are left as ‘isolated islands’ in her model. The inter-connecting straits have not been explored. Her each type of growth remains engulfed in a cassandra of darkness and no rays of light show the path leading to others.

Secondly, Mrs. Robinson contemplates that the prime variable of her model, viz., the rate of capital accumulation gets adjusted to the population growth via adjustments in wage rate, profit rate and labour productivity. This tantamount to suggest redistribution of incomes through the media of relative factor prices. In our view it would be more practical and realistic to deploy fiscal and monetary measures for making adjustments in capital growth vis-a-vis population growth.

Thus, Prof. K. Kurihara writes that “J. Robinson’s chief contribution to Post-Keynesian growth economics seems to be that she has integrated classical value and distribution theory and modern Keynesian saving-investment theory into one coherent system. However, it is not capable of being modified so as to introduce fiscal and monetary policy parameters-unless labour productivity, the wage rate, the profit rate and the capital-labour ratio could be regarded as objects of practical policy-as they might be so regarded in a completely planned economy.”

Thirdly, in the Robinsonian model, State has been completely left out of the picture. It is, indeed, unrealistic and precarious to rely solely on the private entrepreneurs for the achievement of a stable growth of the economy in tune with the requirements of a growing population and rapidly changing technology.

Lastly, Mrs. Robinson’s analysis of steady growth is carried out under the assumption of a given and constant technological horizon. Not only that it is a restrictive and unrealistic assumption, it also rattles the basic logicality of her analysis. For instance, under the given technical conditions when the rate of accumulation happens to be higher than what is required for achieving the ‘golden age’ equilibrium, it will ipso facto alter the pace of technological progress. What is likely to happen in this case is that due to the pressure on the labour-supply, labour-saving innovations and inventions would be stimulated.

Besides, there will be inducement for quick diffusion and introduction of labour-displacing technical improvements which had so far been held back due to an abundant and cheaper supply of labour. Capital accumulation, being the vehicle of technical progress, would, therefore, jeopardise the logical consistency of Robinson’s model which assumes consistency of technical conditions.

Finally, an extension of the above mentioned line of argument sledge-hammers another heroic assumption of Mrs. Robinson. Her model assumes that labour and capital are tethered together in a fixed proportion to produce a given level of output. Absence of substitutability of factors of production would make sense only under fixed and static technical conditions. But in a dynamic setting where technical progress is inherent in the system, technical coefficients of production can no longer remain fixed.

Applicability of Robinson’s Model of Growth to Developing Countries:

We have explained above Joan Robinson’s simple model of capital accumulation which she developed for capitalist economies dominated by free private enterprise. Joan Robinson has distinguished between desired and possible rate of capital accumulation and also presented the concepts of golden ages.

Though Joan Robinson’s model of capital accumulation is relevant for a free enterprise economy in which Government and planning have little role to play, it, however, has some significance for developing countries which have adopted the path of planned development of their economies in which both the private and public sectors coexist and undertake investment activities.

A significant factor which follows from Robinson’s model and which is relevant for developing countries is that investment by private entrepreneurs depends upon the expected rate of profit; the greater the expected rate of profit, the greater the magnitude of investment that they will be induced to undertake. Therefore, whatever reduces the rate of profits, be it imposition of taxes by the Government, increase in the wages by trade unions, fall in the prices of the products will adversely affect investment and therefore rate of capital accumulation and growth. This explains demand side of capital accumulation.

Now take the supply-side of capital accumulation. The volume of investment that will be undertaken and therefore the rate of capital accumulation that will be achieved depends upon the available savings or surplus that will be made from the national income produced over and above the basic or productive consumption, that is–

I=f(S)

Where, I stand for investment and S for saving or surplus. This means that investment is a function of available actual surplus. Now if a part of this basic saving or economic surplus is used for either unproductive consumption by workers or by the capitalist class, rate of surplus actually used for investment will be lower and therefore the rate of capital accumulation will be lower to that extent. In terms of Joan Robinson’s model where rate of profit has been identified with the rate of surplus by assuming that all profits are saved and all wages consumed, rate of profit (k) is given by the following equation–

Where, b is productivity of labour, w/p is the real wage rate ν is the capital-labour ratio.

It is evident from this growth equation that if wages (w) of labourers rise above the level of what is considered as productive consumption, the rate of profit or surplus (π) will be lower which will adversely affect the rate of capital accumulation and growth, productivity of labour (b) and capital- labour ratio (ν) remaining the same.

Now, if the wages remain at the level of productive consumption but a part of surplus created by a worker which is equal to b – (w/p) is appropriated by capitalist class as profits but spent on unproductive or luxury consumption, it will reduce the actual surplus or saving to be used for capital accumulation. Hence we conclude that the lower the propensity of unproductive consumption both by the workers and capitalist class, the higher will be the rate of surplus (or profits) and higher the rate of accumulation.

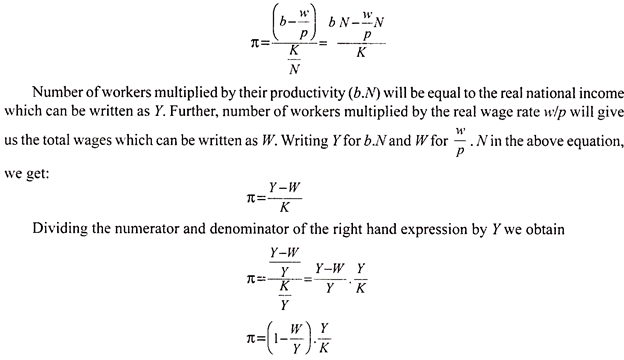

Another important conclusion for Robinson’s model which is significant for the growth problem of developing countries is that there exists an inverse relation between share of wages and the rate of profit. This also follows from the growth equation of Joan Robinson and can be proved as under–

Multiplying the numerator and denominator by the number of workers (N), we get-

It follows from above that given the income to capital ratio Y/K (i.e. output-capital ratio), the rate of profit (π) depends upon the share of wages to national income W/Y. Thus, given the output-capital ratio, the greater the share of wages to national income (W/Y), the lower will be the rate of profit (π) which will adversely affect the inducement to invest and tend to lower the rate of capital accumulation.

But it should not be concluded from above that the rise in wages is not justified from the viewpoint of economic growth under any circumstances. If wages are below what might be regarded as basic or productive consumption which are essential for health and productivity, the rise in wages is likely to raise productivity and efficiency of labour which will cause real national income to rise. With this increase in national income through the rise in productivity of labour, rate of profit or surplus may not fall. Thus, when wages are below the level of productive consumption, as they are in developing countries, the increase in wages will not adversely affect the rate of profit and growth of the economy.

It is important to note that Joan Robinson’s growth model assumes that all profits are saved and also productively invested. As explained above, all profits may not be saved and a good deal of them may be used for luxury consumption. Even if all profits are saved, they may not be productively invested.

A good amount of profits may be dissipated on unproductive type of investment such as for buying gold, jewellery and real estate, building luxury houses, indulging in speculative activities, building inventories of goods, or even building the productive capacity (i.e., capital stock) for the production of luxury consumption goods. These unproductive forms of investment may generate some income and employment in developing countries. But, such unproductive investment will generate more inequalities of income and wealth which will militate against social justice.

In poor developing countries like India, investment can be regarded as productive if it is in the form of either addition to the capacity to produce basic consumption goods or what are now popularly called wage goods or if it is in the form of building capacity to produce those inputs, materials, instruments, machines which are used for producing basic consumption or wage goods such as food-grains, sugar, edible oil, cloth, kerosene oil. The supply of wage goods is essential for the creation of employment opportunities in developing countries.

Thus, it is the rise in productive investment which will expand the output of basic consumption goods and therefore employment and national income. Therefore, the growth of output of basic consumption goods depends upon the share of productive investment to total investment. We, therefore, conclude that the higher the share of productive investment to the total investment, the greater the growth rate of basic consumption goods and of employment.

It may be noted that Mrs. Robinson’s model assumes away foreign trade. Autarky or absence of foreign trade in a world of reality is a completely non-existent phenomenon today. The foreign trade, indeed, plays a vital and propulsive role in the developing economies to bring about rapid economic development.

Above all, the main bastion of the Robinson’s model, viz. ‘capitalist rules of the game’ will not ensure steady and rapid economic growth. In the developing countries there is undeniable an onus upon the State to help accelerate the process of development. The economic responsibility of government in these countries has been established. The fate of these countries cannot be left entirely to the whims and wishes of private entrepreneurs.

It would be well-nigh difficult for these countries to match the rate of growth of population with that of capital accumulation under the banner of ‘capitalist rules of the game’. The debated question today no longer concerns government intervention or not, but how much and how fast.

In fact, Mr. Robinson’s model is itself a dictum against the ‘capitalist rules of the game’. As Prof. Kurihara eloquently remarks, “Joan Robinson’s discussion of capital growth has the subtle effect of discrediting the whole idea of leaving so important a problem as economic growth to the capitalist rules of the game; for her model of laissez-faire growth demonstrates how precarious and insecure it is to entrust to private profit-makers the paramount task of achieving the stable growth of an economy consistent with the needs of a growing population and the possibility of advancing technology.”

Thus Mrs. Robinson’s contribution to the theory of growth brings out clearly that the policy of laissez faire and completely free market will not ensure steady or sustained economic growth. Her model contains various elements which could be very helpful in showing these countries the path to steady growth. For instance, her model brings out cogently that the crux of the problem to achieve steady growth resides in population growth vis-a-vis capital accumulation.

Perhaps the only thing undisputed about the developing countries is the galloping growth of population as the chief hurdle in capital accumulation. With population growth rate being much above the rate of capital formation, these economies exhibit tendencies for increasing unemployment. This situation conforms to the Robinsonian case where ∆N/N > ∆ K /K. As such the journey towards steady growth can be facilitated if the ‘potential growth ratio’ as envisaged by Mrs. Robinson is determined on the basis of growth rate of labour force and of per capita output. The plans can thus be made more realistic and executed more efficiently to achieve the desired goals.