R.A. Mundell stressed not only the need of a monetary-fiscal policy mix to achieve the internal and external stability through his celebrated article. The Appropriate Use of Fiscal and Monetary Policy for Internal and External Stability, but also attempted to provide an answer to a very crucial question concerning the policy priorities in different economic situations like internal unemployment and inflation coupled with external surplus or deficit.

Marcus Fleming, like Mundell, discussed how monetary and fiscal policies work under the fixed and flexible exchange system when there is perfect mobility of capital.

Assumptions:

The Mundellian model rests upon a number of assumptions:

(i) The changes in the size of budget surplus can be treated as an index of fiscal policy. A reduction in budget surplus implies the expansionary fiscal policy and vice-versa.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) The changes in the rate of interest can be viewed as an index of monetary policy. A fall in the interest rate denotes an expansionary monetary policy and vice-versa.

(iii) The exports are exogenously given and imports are a positive function of income.

(iv) The foreign capital is sensitive to the movements in the domestic rate of interest.

(v) There is perfect mobility of capital.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Given these assumptions, Mundell arrived at the following conclusion:

“It has been demonstrated that, in countries where employment and balance of payments policies are restricted to monetary and fiscal instruments, monetary policy should be reserved for attaining the desired level of the balance of payments, and fiscal policy for preserving internal stability under the conditions assumed here.”

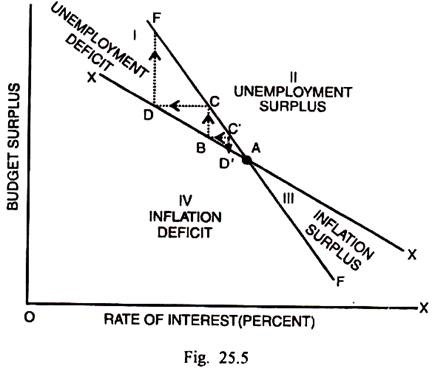

Mundell maintains that a failure to follow this pattern of policy priorities will have a much worse effect than the one it was designed to correct. This can be illustrated through Fig. 25.5.

FF, in this Figure, represents the foreign balance schedule which describes all such budget surplus- interest rate combinations that are consistent with the balance of payments equilibria. FF is negatively sloped because an increase in interest rate, by reducing capital exports and lowering domestic spending and hence imports, improves the balance of payments, while a decrease in budget surplus, by raising domestic spending and imports, worsens the payments position. The points above and to the right of FF denote payments surplus, while points below and to the left of FF represent payments deficit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

XX is the internal balance schedule which describes all such budget surplus-interest rate combinations which ensure full employment without inflation. Like FF, the internal balance schedule XX is also negatively sloped because a decrease in budget surplus will have an expansionary effect upon the system resulting in a rise also in the rate of interest.

An association of smaller budget surplus with higher rates of interest and vice-versa implies a negative slope of the XX function. Though both XX and FF are negatively sloped, yet the latter is steeper than the former. The points above and to the right of XX denote unemployment and recession, while the points below and to the left of XX signify inflation.

The different zones in Fig. 25.5 indicate different economic situations required to be corrected through different monetary-fiscal policy admixtures.

(a) Zone I—Unemployment and BOP deficit.

(b) Zone II—Unemployment and BOP surplus.

(c) Zone III—Inflation and BOP surplus.

(d) Zone IV—Inflation and BOP deficit.

There is a unique point A which reconciles both the internal and external equilibria. Suppose, now the economic system is at point B which is fully consistent with full employment but there is at the same time, the existence of payments deficit. If an attempt is made to remedy this deficit through increasing the budget surplus, the external equilibrium is achieved at C.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This point signifies a state of recession and unemployment. If now the monetary action of reducing the interest rate is employed, the full employment equilibrium is restored at D. The payments deficit, however, gets enlarged at this point. Thus the fiscal action directed to tackle external disequilibrium and the monetary action employed to correct internal disequilibrium cause a progressive worsening of the situation.

On the opposite, if the payments deficit at B is sought to be corrected through an increase in the rate of interest (monetary action), the equilibrium is established at C’. Here the system has the external equilibrium coupled with a state of recession or unemployment. The unemployment is then remedied through a reduction in budget surplus (fiscal action) and the internal equilibrium is established at D’. In this case the monetary and fiscal actions initiate a movement towards the equilibrium position A, signifying the simultaneous achievement of both internal and external equilibria.

Hence the monetary policy should be directed to correct external disequilibrium, while the fiscal policy should be used to correct internal disequilibrium. Any departure from such policy priorities will aggravate further the internal and external instability. “The opposite system”, says Mundell, “would lead to a progressively worsening unemployment and balance of payments situation.”

Criticisms of Mundell-Fleming Model:

The Mundell-Fleming model has been criticised on the following main grounds:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

First, if the economic system is in the zone I (unemployment deficit) or zone III (inflation surplus), the outcome is convergence to point A (See Fig. 25.5), no matter whether monetary or fiscal authority acts first or later. In this connection, it must be recognized that the results will be exactly the same whichever of the two authorities’ acts first or later or whichever instrument is applied first or later.

Second, this model rests upon two implicit assumptions. First, the monetary and fiscal authorities have the full knowledge of the extent to which the economy is away from the external and internal stability so that the appropriate monetary and fiscal policies can be applied. Second, the authorities exactly know the quantitative results that each policy can lead to. In fact, both the assumptions may not hold valid.

Third, although monetary policy should be assigned to external disequilibrium and the fiscal policy to the internal disequilibrium, yet no implication should be derived. The monetary and fiscal authorities should take turn with the policies, or they should act independently or they should operate without the knowledge of what the other does or intends to do. A more realistic and sensible strategy is that the monetary and fiscal authorities should consult and act together. In such a situation, the system can reach the point A in Fig. 25.5 through a more direct path rather than through a zig-zag path.

Fourth, this model leads to an implication that monetary policy is more powerful to deal with external imbalance than the fiscal policy. The reason for it perhaps is that the monetary policy can have a double-barreled impact on the BOP through both capital and current accounts. The fiscal policy, by affecting imports, can operate essentially through the current account.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The fiscal policy however, has an edge over monetary policy in the achievement of external balance. Mundell has termed it as the principle of, effective market classification, according to which “an instrument should be matched with the target on which it exerts the greatest relative influence.”

Fifth, this model considers the cases where inflation or unemployment is associated with BOP deficit or surplus. But it fails to consider the situation in which unemployment coexists with inflation, i.e. stagflation which dominated the world economic scene in 1970’s and 1980’s.

Sixth, when the monetary policy alone is assigned the task of preserving external balance, the capital flows induced to achieve it are essentially of short term character. No country can go on indefinitely with a short term capital inflow offsetting deficits in trade balance. It would create at any rate a situation of precarious BOP equilibrium.

Seventh, this model relates the international capital movements to the changes in the rates of interest but overlooks the degree of sensitiveness of capital flows to the variations in interest rates. The capital flows may be induced by some other factors like changes in exchange rates, money market sentiments, business conditions and political situation. But this analysis overlooks them. In addition, the efforts by one country to encourage or restrict the inflow or outflow of capital may be frustrated by the counter-action of the other countries.

Eighth, the success of the monetary policy rests largely on the sensitiveness of investment demand to the changes in the rate of interest. The relation between the two is influenced by business outlook and expectations but there can be many a slip between the cup and the lip.

Ninth, the fiscal policy is notoriously sluggish. The fiscal measures require legislative sanction which at time becomes available too late and with undesired modifications. The fiscal policy lags are quite long and they reduce considerably its effectiveness in restoring the internal and external equilibria.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Tenth, the monetary-fiscal policy mix is only a palliative. It does not provide a true adjustment process. It does not adjust the balance of payments but simply stabilizes it. The capital flows fill only the excess demand gap in the foreign exchange market, leaving prices and incomes unaffected.

Eleventh, the high interest rate policy, permitting a continuous inflow of capital, can create the problem of debt servicing. Mundell’s model fails to take the measure of this problem and its implication for the BOP disequilibrium.

Twelfth, a high interest monetary policy applied to achieve internal and external stability may cause a decrease in domestic investment. It has to be off-set through tax reduction or increased government spending or both. Such fiscal actions can involve the government in more and more debts. That necessitates the diversion of domestic saving for the financing of government spending supported by debts. It signifies a retardation of capital formation and an inefficient use of domestic saving potential.

Thirteenth, it is not essential that the points of internal and external balance concerning the given country coincide with those of other countries. The different countries may follow conflicting sets of economic policies. It will be a highly complicated process to achieve simultaneously the internal and external balances by all the countries.

Fourteenth, there are practical constraints under which the monetary and fiscal policies operate in a given country. Certain governments may find it difficult, for political reasons, to adopt restrictive fiscal policies. Similarly monetary authorities may also be under constraints and find it difficult to adopt restrictive monetary policies involving reduction in money supply and increase in the structure of interest rates. Mundell did not take cognizance of such constraints.

Fifteenth, there has been, no doubt, a wide recognition that the co-ordinated application of monetary and fiscal policies can effectively help achieve internal and external equilibria. But the internal balance is often given precedence over the external balance. Most of the modern governments are engaged in the difficult task of controlling simultaneously inflation and unemployment. Mundell could not recognise such a situation properly.