In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Comparative Costs Theory Expressed in Money Terms— Taussig’s Contribution 2. Taussig’s Refinement Related to Non-Competing Groups 3. Taussig’s Refinement Related to Charges on Capital.

Comparative Costs Theory Expressed in Money Terms— Taussig’s Contribution:

In the Ricardian comparative costs principle, an assumption is taken that money does not exist and production is measured through inputs of labour. In the modern money exchange system, all exchange of goods occurs through the medium of money. So it is not the comparative differences in labour costs alone, but also the absolute differences in prices that influence the international trade.

Some writers, including Angeil, held the view that the introduction of prices, would lead to conclusions different from those given by the Mill-Ricardo theory. Taussig, however, discounted such a view. He stressed that the comparative differences in labour cost of production can be easily converted into money terms, without in any way, affecting the exchange relations between commodities.

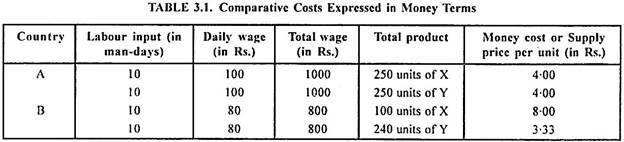

We suppose that 10 days’ labour can help produce 250 units of commodity X in country A. 10 days’ labour in the same country can procure also 250 units of commodity Y. In the other country B, 10 days’ labour produces 100 units of X and 10 days’ labour can yield 240 units of Y commodity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This illustration shows that country A has an absolute advantage in producing both the commodities. But she has a comparative advantage over B in the production of X while B has a lesser comparative disadvantage in the production of Y. Consequently, A will specialize in the production and export of X and B will specialize in Y commodity. Assuming that the daily money wage in countries A and B are respectively Rs. 10 and Rs. 80, this illustration can be converted into money terms.

Table 3.1 shows that per unit money cost of producing X is lower in A than in B. On the opposite, country B can produce commodity Y at a relatively lower per unit money cost. Therefore, country A will specialise in the production of X, while country B will specialise in producing Y commodity. The conclusion is in complete harmony with the Ricardian comparative costs theory.

It may, however, be criticised on the ground that the wage rates in the two countries have been arbitrarily chosen. In fact, this criticism is not valid. There are specific upper and lower limits within which the ratio of money wages between two countries must lie. There is nothing arbitrary about these limits as these are fixed by the comparative efficiency of labour in each country.

In terms of output, country A has an advantage over B in the production of commodity X as measured by (250 units of X in A/100 units of X in A) = 2.5. If now daily wage in country B is assumed as Rs. 80, the daily wage in country A at the maximum can be 2.5 times the daily wage in country B, i.e., Rs. 200. The lower limit is determined by the minimum advantage that country B has over country A in the production of commodity Y. It is measured as (250 units of Y in A /240 units of Y in A) = 25/24.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Given a daily wage of Rs. 80 in country B, the minimum limit of daily wage in country A will be 80 × (25/24) = 250/3 = Rs. 83.33. So if the daily wage in country B is Rs. 80, the daily wage in country A will have to lie between Rs. 83.33 and Rs. 200. There is no possibility of money wage differences going beyond these specific limits.

Suppose the daily wage rises to Rs. 200 in country A, per unit cost of producing both X and Y commodities rises to Rs. 8.00. In this situation, there can be no export of X from A to B because the per unit cost in country B is Rs. 8.00. The import of commodity Y from country B will, however, continue because per unit cost of producing Y in country B remains much lower than the cost in country A.

Such a situation will cause adverse balance of payments, depletion of foreign exchange reserves and gold in case of country A. This will lead to a fall in wages and prices in country A. On the opposite, the wage rate lower than Rs. 83.33, the lower limit of daily wage for country A, will cause adverse balance of payments, depletion of gold and foreign exchange reserves in case of country B.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Suppose daily wage in country A is Rs. 80, per unit cost of producing X and Y both will fall to Rs. 3.20. This will lead to a stopping of exports of Y from country B and country A will continue to export commodity X. The resultant inflow of gold and foreign exchange will increase the supply of money. This will raise the level of daily wages and prices in country A. In this way, it becomes clear that the wage rate will lie between the specific upper and lower limits.

The cost data alone, however, cannot determine where exactly between these limits the actual money wage ratio of two countries and international terms of trade for the two commodities will settle. The Ricardian theory provides no answer to this question. The problem was later dealt by J.S. Mill in terms of the reciprocal demand for the product of each other.

Taussig’s Refinement Related to Non-Competing Groups:

The Ricardian theory had assumed that workers in different counties differ from one another in productivity or efficiency but there is homogeneity of labour within the same country. The implication was that wages differ in different countries but these may be uniform within the same country.

The uniformity of labour in the Ricardian model implied an absence of non-competing groups in a given country. Such an assumption is not valid in actual reality. Even in the same country, there is the existence of different categories of workers such as skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled. These distinct categories or groups of workers are called as non- competing groups. There can be no perfect mobility among these non-homogeneous groups.

Therefore, wage rates are not likely to be the same in all the industries within the same country. The presence of non-competing groups can cause hindrance in international trade and can create serious doubt about the validity of comparative costs theory.

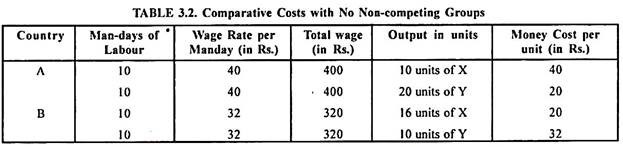

In what way the existence of non-competing groups will affect the international trade, is explained through Tables 3.2 and 3.3. It is supposed that 10 man-days of labour can produce 10 units of commodity X in country A while 20 man-days of labour can produce 10 units of commodity Y in that country. If there is absence of non-competing groups, the wage rates of Rs. 20 in country A and Rs. 16 in country B are in existence. The country B can produce 16 units of X and 10 units of Y.

Table 3.2 shows that per unit cost of producing Y is lower in country A and the per unit cost of producing X is lower in country B. In accordance with the Ricardian comparative costs theory, country A will specialize in the production and export of Y commodity and country B will specialize in the production and export of X commodity.

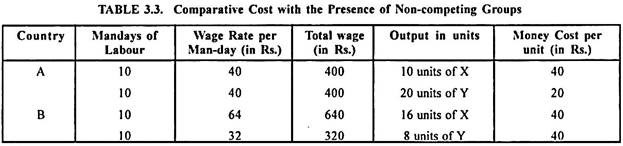

If there is the existence of non-competing groups, let us suppose in country B, there can be problems in international specialisation and trade.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Table 3.3 shows that the wage rates in country B differ between the industries producing X and Y commodities due to the existence of non-competing groups of workers. Country A still produces commodity Y at a lower per unit money cost than the country B and it will, therefore, specialise in the production of Y commodity. But the money unit cost of producing X commodity is the same in the two countries.

So the country B will find difficulty in trade even though it enjoys comparative cost advantage in the production of X commodity in real terms. Similarly a country may have no comparative cost advantage in terms of labour costs but an abundant supply of low-paid workers can enable it to produce the commodities at lower money costs. In such a situation, an abnormally low wage for a particular category of workers can serve as a substitute for real comparative advantage and bring about fundamental changes in specialization and pattern of trade.

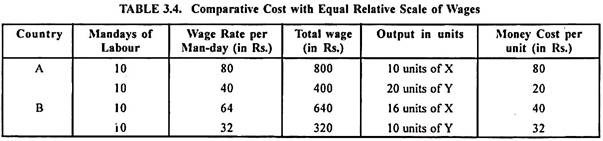

Taussig opined that the simple existence of non-competing groups or non-homogeneous groups of workers cannot affect the traditional comparative costs theory, provided the relative scale of wages in two countries remains the same. If the structure and relative wages of non-competing groups are similar from country to country and the input requirements for any given product in case of different groups remain unchanged, the unit money costs or prices will be affected in the equal degree. In these circumstances, the Ricardian principle of comparative cost advantage can still remain valid. This may be explained through Table 3.4.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The table rests upon the assumption that non- competing groups exist in both the countries A and B. The relative wage scale is also the same in the two countries. The wage rates in industries producing X and Y commodities in country A are Rs. 80 and Rs. 40 whereas these are Rs. 64 and Rs. 32 in country B.

Since the unit money cost in country A is lower in the case of Y commodity than in country B, the former will specialise in the production and export of Y commodity. Country B, on the other hand, produces X commodity at the lower unit money cost than country A. Therefore, it will decide to specialise in the production and export of X commodity.

So Taussig pointed out that the comparative costs theory can still remain valid despite the existence of non-competing groups. In the words of Taussig “…If the groups are in the same relative positions in the exchanging countries as regards wages—if the hierarchy, so to speak, is arranged on the same plane in each—trade takes place exactly as if it were governed by the strict and simple principle of comparative costs.” So with a few exceptions only, the Ricardian principle can hold valid in its original form.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A further modification has been attempted by Ellsworth in this regard. He believes that the existence of non-competing groups can do absolutely no damage to the Ricardian doctrine if, apart from same labour hierarchy, it is also supposed that the wage scales and relative numbers of workers in various groups in the two countries also do remain the same.

Taussig’s Refinement Related to Charges on Capital:

The Ricardian theory of comparative cost advantage considered labour alone as the productive factor and wages as the only constituent of money cost. But that assumption is not true in real world. The interest, a charge upon capital, too has much impact on money cost because labour is often used in conjunction with capital.

Taussig explained that the comparative costs theory does not require any modification if in both the trading countries the interest rates and capital- labour ratio are exactly the same. In such a situation, since all prices are affected equally in the two countries, the classical theory can explain the pattern of specialization and trade. There is again no need of any modification upon the original theory, even if there are differences in interest rates and capital- labour ratio in two countries, provided these differences are applicable to all goods in the same measure.

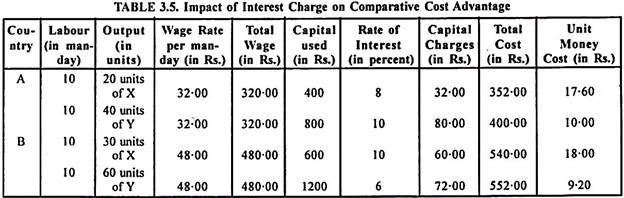

Taussig specifies that the need for amendment in the traditional theory arises only when burden of capital charges is different on different commodities in the different countries. A very low rate of interest can ensure some comparative advantage for the given country and influence the pattern of specialisation in production and trade. Such a situation is detailed through Table 3.5.

According to Table 3.5, if interest cost is not considered, there are equal differences in cost and trade cannot be possible between the two countries A and B. When the interest rates applicable to industries producing X and Y commodities in the two countries are taken into account, the unit money cost in the production of X commodity is lower (Rs. 17.60) in country A than in country B (Rs. 18.00).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the other hand, the unit money cost of producing Y commodity is lower (Rs. 9.20) in country B than the country A (Rs. 10.00). It means the country A now enjoys comparative cost advantage in commodity X while B has advantage in the production of Y commodity. Accordingly, country A will specialise in the production and export of X commodity and country B will specialise in the production and export of Y commodity. In this way, the charge on capital can make a significant difference in the pattern of international trade.

No doubt, Taussig has analysed in detail the impact of capital charge on comparative advantage and the pattern of trade, yet he believes that the quantitative significance of this theoretical amendment is very limited. It is so because of the reason that neither the interest rate differentials nor the differences in the relative use of capital in the industries of advanced countries are very large.

However, there are very significant differences in these two respects between the advanced and less developed countries. It may, therefore, be concluded that the charges on capital can become a very crucial factor in deciding the comparative advantages in the trade between advanced and the less developed countries.