In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to Higgins’s Theory 2. Technological Dualism and the Aggravation of Unemployment Problem 3. Evaluation.

One of the most significant consequences of dualistic development is to be found in the pattern of employment. The fact that the unemployment problem has assumed alarming proportions in the developing countries is indicative of some sort of fundamental disproportionality in the production relations inherent in dualistic development. Boeke’s exposition of social dualism did not recognise any such thing.

However, in recent times increasing number of writers have attempted to explain the unemployment problems of developing countries in terms of what has come to be known as ‘technological dualism’. The chief exponent of this theory is Benjamin Higgins. This theory incorporates the problem of factor proportions in the production of commodities.

It is held that the chief cause of rather inelastic productive employment opportunities in the developing countries is not the deficient effective demand. Rather it is due to the technologically dualistic nature of these economies. The fundamentally different production functions and factor endowments in the advanced and the backward indigenous sectors of the economy are responsible for generating an ever-increasing volume of unemployment. Therefore, the unemployment associated with dualistic development is structural or technological in nature.

Introduction to Higgins’s Theory:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Higgins explains his theory of technological dualism on the basis of a model in which there are two commodities, two factors of production and two sectors, viz., the modern and traditional sectors. The dichotomy between the two sectors is sharply defined chiefly on the basis of the distinctly different factor endowments and production functions attributable to each of these.

The traditional rural sector is engaged primarily in peasant agriculture and the handicrafts or very small-scale industries. However, the most distinctive feature of this sector is the flexibility in the techniques of production. The products can be produced with a wide range of alternative input-mix. With the possibility of easy substitutability between capital and labour, a wide spectrum of techniques could be employed in production of this sector. They range from the wooden plough to the modern tractor and from the sickle to the harvester. As such, the chief characteristic of the production function in the traditional sector is the prevalence of variable technical coefficients of production.

Associated with the phenomenon of fairly wide range of technical substitutability is pro-labour factor endowments, i.e., while labour is abundant, capital is the relatively scarce factor of production. The result is that labour-intensive techniques are chosen in the traditional sector for the production of commodities. As distinct from this, we have the modern sector consisting of large-scale industries, oil fields, mines and plantations.

The main feature of this sector is the use of fixed technical coefficients of production. That is, the elasticity of substitution between the factors of production is almost zero. With the almost total absence of technical substitution, the production of a particular commodity in the modern sector requires a particular technique and none else to be adopted. And the production process is capital-intensive in nature.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

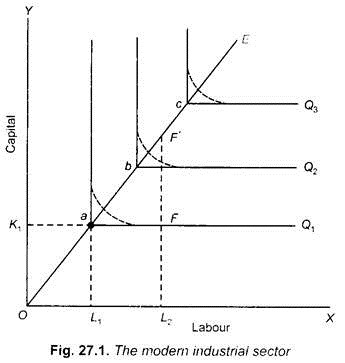

The production function of the modern sector can be diagrammatically represented in Fig. 27.1, given below:

Here the units of labour (L) are measured along the horizontal axis and those of capital (K) are represented along the vertical axis. The curves Q1, Q2, Q3 are the isoquants depicting different levels of output. The rectangular shape of the isoquants indicates that the different levels of output can be produced only by a unique combination of the factors capital (K) and labour (L). For instance, the output level Q1 could be attained only by combining capital and labour in the amounts OK1 and OL1, respectively.

Thus, the points a, b and c around which the isoquants turnabout perpendicularly, represent the fixed combinations of capital (K) and labour (L), that are required to produce the output levels Q1, Q2 and Q3 respectively. In such a production function no matter what the relative factor prices are, the factor proportions remain fixed.

The expansion path of output is given by OE—obtained by joining the points, a, b and c. It shows that the output can be increased by increasing the factor inputs K and L, in the proportion given by the slope of the line OE. The slope of the expansion path OE, as is clear from Fig. 27.1, gives a relatively capital-intensive factor ratio. In other words, a greater quantum of capital relative to labour is required to produce a given level of output.

Now, given the fixed capital-labour ratio as obtaining in the production process and given the factor endowments, the question is, will the factors be simultaneously fully utilized? The simultaneous full utilization of factors will be possible only when the proportions in which they are available is exactly equal to the fixed capital-labour ratio—as given by the expansion path OE. However, if there is a deviation in the factor proportionality—as between the actual factor endowment and that necessitated by the productive process, at least one of the factors would be less than fully utilized.

Let us suppose that the actual factor endowment is represented by a point such as F, situated to the right of the expansion path OE. That is OK1 amount of capital and OL2 units of labour are available in this sector. But to produce the output level given by the isoquant Q1, we need OK1 units of capital and only OL1 number of labour. Thus, L1L2 number of labour will remain surplus; no matter how favourable is the relative price of labour vis-a-vis capital. As production in this sector depends on the basis of fixed technical coefficients, this surplus labour will remain unemployed.

The only way to eliminate the unemployment of L1L2 units of labour, is to increase the capital stock by the amount FF’. If capital accumulation of this order fails to take place, there is no possibility of that redundant labour force being absorbed in the modern sector. It will have either to fall back upon the agricultural sector or remain unemployed. Since the technical coefficients of production in the agricultural sector are variable, the surplus labour force can get absorbed there, making the techniques of production still more labour-intensive.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, in practice the technical coefficients of production in the modern sector are not all that fixed. There is possibly some—though very limited—amount of substitution between the factors. The dotted curves, drawn in the angles of the isoquants, represent this limited degree of flexibility in the factor proportions. But the fact is that such small changes in factor proportions would hold no attraction for the entrepreneurs to undergo the pains of effecting drastic shifts in the production techniques. They would rather prefer to continue operating on the fixed techniques of production.

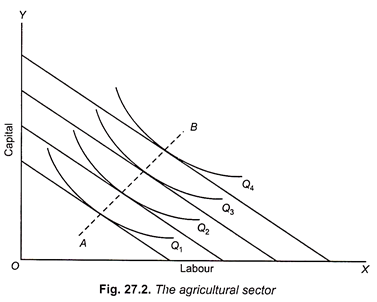

In contrast to this, the flexibility of factor proportions in the agricultural sector is depicted by Fig. 27.2. Here the technical coefficients of production are variable, a given level of output can be obtained through a wide range of techniques, and hence with a wide range of combinations of labour and capital. Thus, the factor proportions being actually used would be in consonance with its given factor endowments. And, therefore, the techniques employed in this sector would depend on the prevailing relative prices of labour and capital.

Technological Dualism and the Aggravation of Unemployment Problem:

With the two sectors possessing typical and distinctly different configurations of the production functions, it is now easy to trace as to how technological dualism has aggravated the problem of unemployment and disguised unemployment in developing countries. Generally, the modern sector in these economies experienced a rather quick expansion, especially with the inflow of foreign capital and enterprise. As a sequel to this economic expansion, there also occurred in this sector rapid growth of population. In fact, the rate of population growth tended to outstrip the rate of capital accumulation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But with its capital-intensive techniques and fixed coefficients of production, it was not possible for the modern sector to generate adequate employment opportunities commensurate with the growth of population. The consequence was that labour became a surplus factor in this sector. The only course open to this redundant labour was to shift to the traditional agricultural sector.

The redundant labour so released by the modern sector goes to increase the supply of labour in the traditional agricultural sector. In the initial stages, it may be possible to bring more land under cultivation to engage the excess supply of labour. However, eventually the inelastic supply of land exhausts all possibilities of extending cultivation. Meanwhile, the redundant labour continues pouring into the traditional sector. Now, the technical coefficients of production being variable in this sector, the entire additional labour is absorbed. But all this is at the expense of reduction in the capital intensity of the production process. It becomes ever more labour-intensive. Eventually, highly labour-intensive cultivation extends to all the available land. As such, the marginal productivity of labour declines to zero or even below that, the result being the emergence of disguised unemployment on a substantial scale.

Thus, continued growth of population striking against limited capital stock gives rise to surplus of labour. There then comes the stream of unproductive workers who appear to be employed but, in fact, they constitute the ranks of disguisedly unemployed, for they add virtually nothing to the output.

Under such conditions, there is no reason for the farmers to seek to apply labour-saving innovations, even if it is granted that they know about them and have resources to finance them. This apart, even the incentive on the part of labour itself to put in increased efforts is not to be found on account of the surplus supply of labour. The result is that productivity and earnings of labour and their well-being remain low as ever.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Further, it is held that the nature of technical progress is such that, even in the long run, it does not alleviate the problem of unemployment. In the modern sector, the technical progress has tended to be capital-using thus accentuating the unemployment problem. On the other hand, until recently, that is prior to green revolution there was little technical progress in the traditional sector, on account of the lack of complementary inputs and the smallness of the scale of operations.

Besides, the problem of disguised unemployment tends to be all the more accentuated on account of the artificially bolstered up wages as a result of trade unionism or by government policy. Such a phenomenon of industrial wages outstripping the productivity further stimulates the adoption of labour-saving techniques. So that the capacity of the industrial sector to absorb population growth is all the more undermined. All these factors continue to reinforce and perpetuate the problem of disguised unemployment in the developing countries.

Evaluation of Higgins’s Theory:

Higgins’s theory of technological dualism definitely marks a march over Boeke’s sociological dualism. It brings out elegantly the underlying cause of the historical increase of underemployment in the traditional and agricultural sectors of underdeveloped countries. However, Higgins’s contention that production in the modern sector is invariably carried on with fixed technical coefficients is contestable. In some sectors of the industrial sector such as textiles, leather and leather products, electronics and sugar, there is a good scope for variability of factor proportions. Even in these cases in countries like India, capital-intensive technologies have been used. This is partly due to the factor price distortions, that is, while price of scarce capital has been lower but wages of abundant factor higher relative to their availabilities.

In 1971, a prominent development economist, Gustav Ranis wrote, “The Koreans and the Taiwanese are showing a wide range of technological choice in textiles, in electronics and in plywood industries, during the last decade. What the Japanese were doing relative to British and American machinery in the nineteenth country, the Koreans and Taiwanese are now doing relative to the Japanese as well as the American technology. They produce the same quality textiles or plywood or transistors with three to four times as much labour input per unit of capital. The sub-contracting which can be so important a feature of labour-saving technological change is being used increasingly at an international level as exemplified by the export-bonded processing schemes in both Korea and Taiwan.

It follows from the examples of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan that factor proportions in the production of manufactured products are not so rigid as has been made out by the theory of technological dualism. Contrary to the factor endowments of developing countries, for the use of capital-intensive technologies in the modern sectors, advanced developed countries are to blame because the tendencies of foreign private investors as well as official policy of the developed countries with respect to foreign aid often encourage the adoption of capital-intensive technologies in the recipient countries.

Further, multinationed corporations which play an important role in the industrial development of the developing countries are unlikely to spend much time in investigating alternative technologies which are more labour-intensive and better suited to the labour-surplus conditions of developing countries. They prefer to install plants of their mother countries which embody highly capital-intensive technologies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Besides, the practice of tying foreign aid to developing countries by the donor countries to purchase capital-intensive capital equipment from them promotes the use of capital-intensive technologies. Further it has been found that the producers in the developing countries often attach prestige value to installing modern capital-intensive equipment of latest technology imported from the developed countries.

They themselves are not interested in investigating through R&D activities the labour-using technologies that are more suited to the factor endowments of the developing countries. Further, Gustav Ranis rightly writes, “Even if we concede that there are absolutely no technological choices, there is still the question of changes in output-mix (i.e., the production of various products) which should make it possible to adjust one’s production structure in line of factor endowment.”