In this article we will discuss about the theory of protection which is a highly important issue in foreign trade. The foreign trade policy has been the subject of heated discussion since the time of Adam Smith who advocated for free trade and recommended that tariffs should be removed to avail of the advantages of free trade. Even today, economists are divided over this question of foreign trade policy. Various arguments have been given for and against free trade.

If the policy of protection of domestic industries is adopted, the question is whether for this purpose tariffs should be imposed on imports or quantitative restrictions through quota and licensing are applied. In India certain political parties and groups have been demanding a policy of Swadeshi which in essence means that domestic industries should be protected against low-priced imports of goods from abroad, that is, free foreign trade should not be allowed.

Besides Adam Smith, the other famous classical economist, David Ricardo, in his famous work “On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation” also defended free trade to promote efficiency and productivity in the economy. Adam Smith and the other earlier economists thought that it pays a country to specialise in the production of those goods which it can produce more cheaply than any other country and import those goods which it can obtain at less cost or price than it would cost to produce them at home. This means they should specialise according to absolute cost advantage.

However, Ricardo put forward the ‘Theory of Comparative Cost’ where he demonstrated that to obtain benefits from trade it is not necessary that countries should produce those goods for which their absolute cost of production is the lowest. He proved that it could pay a country to import a good even though it could produce that good at a lower cost, if its cost is relatively lower in the production of some other good. Ricardo’s theory of trade rests on the idea of relative efficiency or comparative cost.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Despite the classical arguments for free trade to promote efficiency and well-being of the people, various countries have been following the protectionist policies which militate against free trade. By imposing heavy tariff duties on imports of goods or fixing quotas of imports they have prevented free trade to take place between countries. Several arguments have been given in favour of protection. We explain below the various arguments given in favour of protection.

Case for Protection:

Despite gains from free trade, many arguments have been given against free trade and in favour of protection. By protection we mean in order to safeguard the domestic industries from low-priced imports some barriers against import of foreign goods are imposed. Some arguments given in defence of protection are irrational and invalid, whereas some are valid. We critically examine below various arguments given in favour of protection (i.e., against free foreign trade). Protection has been defended on the basis of nationalistic feeling. It has been said that patriotism requires that people of a country should buy products of their domestic industries rather than foreign products.

In the USA there has been a campaign “Be American, buy American” appealing people to buy American goods instead of imported foreign products. Similarly, in India the campaign of ‘Swadeshi’ appeals to the patriotic feeling of the Indian people that we should protect our indigenous industries and impose barriers on imports of foreign goods or provide subsidies to our industries. However, this argument is misplaced and invalid.

Those policy-makers who yield to such arguments deny the people of a country the gains from trade such as rise in productive efficiency and greater well-being, stimulus to growth through higher capital formation and spread of superior technology. The policy of protection in the name of nationalism or swadeshi is actually contrary to our national interests because it promotes inefficiency and prevents rapid economic growth. However, in defence of protection important economic arguments have been given which we will critically examine below.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Employment Argument:

An important argument for protection is that it will lead to increase in domestic employment or at least preserves present domestic employment. It is often believed that imports of goods from abroad reduce domestic employment. Therefore, if instead of imports we produce those goods at home, employment in the country will increase.

Besides, as prices of imported goods are lower, the domestic producers would not be able to compete with them and may be competed out of the market. This will destroy even present jobs in the domestic industries. It is therefore concluded that protection of domestic industries will lead to their expansion and therefore employment in them will increase.

In our view employment argument for protection is not logical and valid. This argument ignores the adverse effects of protection on our industries. An important economic principle is that exports must pay for imports. If imports are restricted by imposing barriers, the exports cannot remain unaffected. For example, many raw materials and capital goods are imported to be used in domestic industries which export goods. If imports are restricted, exports will therefore fall. This will lead to the decline in employment in export industries which will offset the increase in employment in the import-substituting industries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Further, when you restrict imports to protect domestic industries so that they should expand, other countries are likely to retaliate and will impose restrictions on our exports which are imported by them. This too will reduce exports and cause reduction in employment in export industries. Thus net effect on employment of restricting imports for providing protection to domestic industries may not be positive.

Infant Industry Argument:

A powerful argument given in support of protection, especially in the context of developing countries, is that infant industries should be provided protection from the competition of low-priced imports of the mature and well-established industries of the industrialised developed countries. Shortly after American Revolution, Alexander Hamilton argued that British industrial supremacy was due to its early start over American infant industries.

He pointed out that these infant American industries required temporary protection for some time so that they should grow and achieve production efficiency and economies of scale before they could successfully compete with low-cost British goods. He thus argued that temporary protection of infant American industries was necessary for industrial development of America.

Similarly, the infant industry argument has been advanced for protecting infant industries of the developing countries from competition of the low-cost firms of the industrialised developed countries. It has been argued that, given some time, these infant industries will grow and will be able to benefit from the economies of scale and learn the techniques necessary to lower their cost of production.

As a result, over a period of time their cost per unit will go down and these industries will therefore be in a position to compete with the foreign imports. Therefore, for some time they should be protected otherwise they would be destroyed by foreign competition.

However, there are some lacunae in infant industry argument. First, it is assumed that protected infant industries will make efforts to lower cost when provided protection. However, actual experience shows that it is more likely that protected industries lose incentives to become efficient and lower cost. It is said “once an infant, always an infant.” Secondly, even if an industry makes efforts to improve productivity and lower cost per unit when it is provided protection, it has been assumed in the argument that the Government is the best judge as to which industries will prove to be capable of competing low-priced foreign goods.

It has been asserted in defence of free trade that selection of industries which will acquire competitive strength can be done better by private market mechanism. It is pointed out that when opening up the economy to foreign competition the domestic industries would try to increase their efficiency.

As a result, only those industries will survive which are efficient and produce at a lower cost. Therefore, it is better if the domestic industries are left to foreign competition and in this way they will have incentives to improve productivity to escape from losses. Only those domestic industries will survive and operate which are efficient and produce at a low cost per unit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Indian automobile industry is a shining example of an industry not making any efforts to become efficient even after given protection for more than three decades. Before the setting up of Maruti Udyog with Japanese collaboration, Indian car industry was fully protected by heavy duties on imports of cars. The two domestic firms producing Ambassador and Fiat cars did not make any efforts to improve their efficiency, nor did they bring out any better models of their cars. It is only after 1991 following the policy of liberalisation that new foreign firms such as Daewoo of South Korea, General Motors of the U.S. have come in India and are producing new models and at relatively low prices. Even Maruti is now trying to improve its efficiency further and brought out new models of Maruti such as Aristo and Esteem.

However, it may be noted that in developing countries the Government is in a better position to protect certain industries such as steel and cement which lead to an expansion of the infrastructure of the developing economies. This is because these industries create external economies and the private firms will not be compensated for creating these external benefits.

Anti-Dumping Argument:

The other important argument for protection is that foreign producers compete unfairly by dumping the goods in another country. Dumping is a form of price discrimination when producers of a country sell goods in another country at lower prices than those charged at home. Of course, consumers in a country in which foreign goods are dumped are beneficiaries; the industries of that country suffer as they are unable to compete with the ‘dumped goods’. Besides, there is more harmful ‘predatory dumping’ which implies that foreign firms try to sell goods in other countries even below their cost to establish a worldwide monopoly by driving competitors out of the market. Once the local industries are competed out, they raise prices to obtain monopoly profits.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There is a lot of evidence that firms of USA and Japan often indulge in dumping of their goods in other countries to eliminate competition. But, in our view, instead of providing protection to domestic industries through tariff or non-tariff barriers, it will be a better policy to enact laws against dumping. Dumping should be prohibited by law declaring it illegal. In India such a law has been enacted but is not being properly implemented.

Correcting Balance of Payments Deficit:

Correcting deficit in balance of payments is also mentioned as justification for imposing tariffs to restrict imports or fixing of quotas of imports. This appears to be a valid argument for providing protection. Due to rising imports of raw materials and capital equipment for their industrial development, the developing countries often face deficit in their balance of payments. Because of the protectionist policies by the developed countries, their exports have not been increasing.

To finance the deficit in their balance of payments, they often borrow from abroad. This ultimately leads to increase in their burden of debt which leads to foreign exchange crisis. This happened in case of India when it borrowed heavily from abroad during the nineteen eighties to finance its industrial growth which resulted in balance of payments crisis in 1990-1991. This too happened in case of East Asian countries some of whom also grew through foreign borrowing and landed themselves in foreign exchange crisis.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Therefore, many economists have argued that developing countries adopt protectionist policies to achieve sustained growth. However, in our view the solution for fundamental disequilibrium in the balance of payments lies in the adoption of suitable adjustments in exchange rate, appropriate fiscal and monetary policies to lower domestic prices so as to encourage exports. The deficit in balance of payments can be reduced by ensuring rapid growth in exports of a country.

Conclusion:

We have critically examined the various arguments in favour of protection. Some of them are valid, others appear to be misplaced. Some people consider trade as a ‘zero sum game’ that is, in trading if one gains, the other loses. This has given rise to the doctrine of exploitation.

For example, it is believed by some that the developing countries like India are exploited by the developed countries such as the USA, Japan and Britain. That is, the developing countries are net losers in trading with the developed countries. However, in our view, this is wrong thinking.

No trade can occur without expectations of gain. India would not have entered into trade relations with USA if it did not expect to gain from it. Trade occurs between two countries if it benefits both the trading partners, the developed and the developing countries. Therefore, in our view world trade should be promoted by lifting barriers put up by various countries based on wrong notions about effects of free trade. Some countries such as USA and Japan have resorted to protectionist measures as retaliation against foreign countries that restrict imports into their countries.

The retaliatory actions of imposing trade barriers have done great harm to the expansion of world trade. New International Organisation WTO (World Trade Organisation) which has replaced earlier GATT has framed rules which every country should observe so that barriers to trade are removed and world trade be promoted without doing any injustice to the member countries. It may be noted that retaliatory activities of restricting imports from foreign countries generally lead to the depression in the economies of the world as it happened during the worldwide depression of 1930s. The retaliatory activities may cause another global depression.

Tariff and Protection:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Tariff is an important means of protecting domestic industries against competition from the low prices of imported products. The rates of the tariffs are not so high as to completely prohibit imports into the country. Rise in prices of imported products as a result of imposing tariffs, foreign producers lose their competitive strength. There are two main reasons advanced for protection of domestic industries from imports by developing countries. First, the developing countries which adopted import-substituting industrialisation of their economies require to replace the imports by producing the goods at home.

This requires the protection of their infant industries which had higher unit cost of production. It was pointed out that once the infant domestic industries have recorded sufficient growth, they will be able to enjoy the economies of scale and also gain through learning by doing, their unit cost of production will fall and enable them to compete with the imported foreign products. In the meantime they need protection from imports by the imposition of tariffs. The imposition of tariffs on the imported products raises their prices and thereby provides protection to the domestic industries producing those products.

It is worth mentioning that most of the developed countries registered industrial growth by protecting their industries through levying tariffs. Once having been industrially developed they become champions of free trade. However, even now, when agreement has been made about reduction of tariffs, they prevent the entry of labour-intensive manufactured products of developing countries through one way or the other.

It has been pointed out by Todaro and Smith that “WTO rules eliminated many formal barriers but many implicit barriers remain. Anti-dumping investigations increased significantly, reaching a peak in 1999 and the United States was the largest user of these protectionist measures. Although the number of new investigations declined in the early years of the new century, they remained an important weapon in the protectionist arsenal. Countervailing duty impositions are also on the rise. Regional trading agreements, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the EU may also have the effect of discriminating and the EU may also have the effect of discriminating against exports from non-member developing countries.” Thus, the protectionist measures still being adopted by the US and EU further induce the developing countries to protect their industries from unfair foreign competition.

Second, it has been argued that, since many developing countries face difficulties of balance of payments, they have to restrict imports to reduce their current account deficit (CAD). For example, in India due to heavy imports, its current account deficit has exceeded 4 per cent of GDP in some years. As foreign capital flows are very volatile, sometimes it becomes difficult to finance the deficit and recourse has therefore to be made to use foreign exchange reserves held by the Reserve Bank of India to finance it. As the foreign exchange reserves with the RBI are limited, they cannot be a permanent solution of the deficit in balance of payments.

In view of the balance of payments difficulties faced by the developing countries, they raise tariffs to reduce imports and thereby improve the balance of payments situation. Thus, in case of developing countries, “Although initial costs of production may be higher than former import prices, the economic rationale put forward for the establishment of import-substituting manufacturing operations is either that industry will be able to reap the benefits of large-scale production and lower costs (the so called infant industry argument for tariff protection) or that the balance of payments will be improved as fewer consumer goods are imported”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Diagrammatic Illustration of How Tariff can be used for Protection:

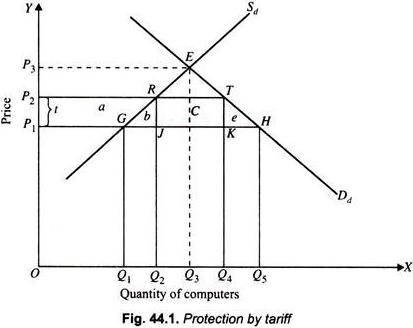

We now explain how tariff can be used to protect an industry. Let us take a product, computers, in which India does not have a comparative advantage. The protective effect of levying tariff on the import of computers from the US can be illustrated through simple demand and supply curves of computers in India. In Fig. 44.1, we have drawn domestic demand curve Dd and supply curve S d of computers in India. These domestic demand and supply curves of computers intersect at point E. In the absence of foreign trade in computers, the domestic price P3 is determined at which quantity OQ3 of computers is produced and sold in India.

Suppose India opens up to world trade, where the price P1 prevails. Since India’s market for computers is quite small relative to the total world market, it will take the world price P1 as given for it and therefore can buy computers as much as it likes at the world price P1.

As a result, with free trade the consumers of India will buy the quantity Q5 at price P1 as indicated by the domestic demand curve Dd. Note that as compared to the quantity Q3 in case of no trade, with free trade quantity purchased by the domestic consumers has risen to Q5 at the lower world price P1. However, the domestic producers of computers will supply only the quantity Q1 at world price P1. The remaining supply of the computer Q1Q5 (= GH) will be imported at world price P1. Thus, with free trade the domestic producers of computers will be adversely affected.

Now suppose, to protect its domestic computer industry Indian Government imposes a tariff ‘t’ on the imports of computers. Suppose with this tariff the price of imported computers rises from P1 to P2. At this higher imported price P2,the quantity demanded by the domestic consumers will fall to Q4 and the quantity supplied by the domestic producers of computers will increase to Q2 and the remaining quantity demanded equal to Q2Q4 (= RT) will be imported. Thus, with the imposition of tariff the domestic producers have gained as their production has increased to Q2. However, with imposition of tariff the consumers have suffered a loss of consumer surplus equal to the total area P1HTP2 which consists of areas a + b + c + e. With the imposition of tariff equal to P1P2 the Government has earned the revenue equal to the rectangular shaded area JKTR which it can use for other purpose.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It may be further noted that if Government raises tariff on computers equal to P1P3, the imports will fall to zero and the whole quantity demanded at price P3 will be met by the domestic producers of computers. But with such a prohibitive tariff though the domestic computer industry has got full protection, the consumers have suffered a great loss of welfare as a result of protection they have now been deprived of purchasing imported cheaper computers.

Effective Rate of Protection:

To what extent the imposition of a tariff on an industry’s product provides protection to it requires a proper measure. The rate of tariff imposed on a commodity raises the price of the commodity and therefore the percentage by which the domestic price rises as a result of levying tariff represents the nominal rate of tariff. The nominal rate of tariff is there for defined as-

t0 = (Pt-P) / P

Where, Pt is the domestic price inclusive of tariff (i.e., with protection) and P is the price without tariff (i.e., under free trade).

For example, if a particular model of a car has domestic price inclusive of tariff equal to Rs 5 lakh and its import price at the entry at port (i.e., CIF or cost, plus insurance plus freight) is Rs 4 lakh, then nominal rate of tariff (t) would be (5-4)/4 = 1/4 =0.25 . However, nominal rate of tariff does not correctly reflect the extent of protection to an industry. To find the actual degree of protection one must not only consider the tariff on the final product but also the tariff, if any, on the intermediate inputs that the industry uses to produce the final product.

This implies that for measuring actual or effective protection received by an industry we should consider value added by an industry. Note that the value added by an industry equals the sum of wages, interest, rent and depreciation allowance payable by the firms in the industry. Effective rate of protection of an industry is the extent (i.e., percentage) by which value added by an industry at the domestic price as a result of protection (i.e., inclusive of tariff) exceeds the value added if the industry had got no tariff protection from the foreign imported product and had to face unrestricted competition in the free world market.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, the effective rate of protection is the difference between the value added at domestic prices inclusive of tariff and the value added at the world prices (i.e., without protection) expressed as percentage of the latter. Thus the effective rate of protection can be measured in the following way–

Where, ERP is the effective rate of protection, Vd is the value added by the industry with protection (i.e., inclusive of tariff) and Vw is the value added at world price (i.e., without protection). The effective rate of protection depends on the extent Vd is greater than Vw which is determined by the rate of tariff on the intermediate inputs used by the industry. Note that imposition of tariff causes domestic price to rise above the world price of the product.

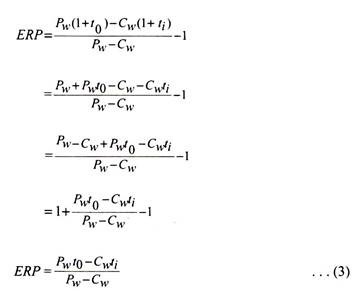

The above measure of the effective rate of protection can be further refined. The difference between the values added per unit of output at domestic price (inclusive of tariff) and the cost per unit of output of intermediate inputs used for its production (Cd). Note that domestic price (Pd) is equal to world price (Pw) plus ad valorem tariff (t0) on competing imports.

On the one hand, domestic cost equals cost at world prices (Cw) plus the ad valorem tariff, if any, on intermediate material inputs (ti), that is, value added at domestic pries (Vd) per unit of output equals Pd – Cd and value added at world prices equals Pw – Cw. Given these expressions effective rate of protection given in equation (1) can be rewritten as-

As we are considering ad valorem tariff (which is percentage of world price, Pd= Pw+ Pw t0 = Pw (1 + t0). Likewise Cd = Cw+ Cwti= Cw(1 + ti ) where t0 is the tariff on the finished product and ti is the tariff on intermediate materials input. With this the effective rate of protection given in equation (2) above can be written as –

Thus, the effective rate of protection depends on the following factors:

1. The nominal rate of tariff on the finished product (t0);

2. The world price (Pw) of finished product and the world price of material inputs (Cw);

3. The nominal rate of tariff (ti) on the imported intermediate material inputs of the finished product; and

4. The value added at world prices, that is, Pw – Cw.

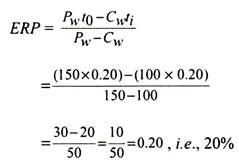

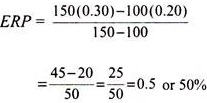

We now give a numerical example of calculating effective rate of protection by giving some examples using equation (3) above. Suppose that $150 worth of cloth valued at world prices will need $ 100 of imported material inputs such as cotton and dyes valued at world prices. In this case the value added by cloth is equal to $ 150 – 100 = $ 50 at world prices.

Now, if Government levies import duty (i.e., tariff) of 20% on both the competitive imports of the finished cloth and material inputs of cotton and dyes, then the effective rate of protection is-

It follows from above that if the uniform nominal rate of tariff is levied on both the final product and the material inputs, the effective rate of protection (ERP) will equal the nominal rate of tariff.

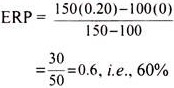

However, in order to protect investment in an industry, the Government levies 20% tariff on the import of computers (i.e., final product) and no tariff on the imports of material inputs used in the production of computers, then –

Thus in this case effective rate of protection is 60 per cent, that is, 3 times the nominal rate of tariff of 20% on the final product.

Take the third example. Suppose that on the imported computer the import duty is 30 per cent whereas the import duty on its material inputs is 20 per cent, then –

It follows from the last two examples that the modest nominal protective tariff rate of 20% and 30% on the final product provides much higher, 3 times and 2.5 times respectively, of effective rate of protection. The higher effective rate of protection to an industry encourages business men to invest more in the industry as it yields much higher value added which not only gives them more profits but also enables them to pay higher wages, interest and rent. This ensures the faster development of the domestic industry of the country which will enable it to substitute imports.

It is also worthwhile to note that the effective rate of protection is generally greater than nominal rate of tariff. But if nominal rate of tariff on the competing imports of material inputs is greater than that on the finished product, then the effective rate of protection will be negative. However, this form of tariff structure is unlikely to exist in the real world. In actual practice, the consumer goods industries in the developing countries are highly protected to ensure import-substituting industrialisation.

The capital goods in the developing countries get less degree of protection because high tariffs on capital goods discourage investment in the developing countries. Thus, in actual practice the performance of most of the developing countries is quite disappointing. Their poor performance in respect of industrial growth is attributed to some extent the high effective rates of protection provided to the final consumer goods and less effective protection to the intermediate and capital goods industries. This has resulted in more allocation of scarce resources to inefficient production of highly protected final consumer goods by the developing countries with the development of indigenous capital and intermediate goods industries remaining underdeveloped. This has caused rise in costs of production of domestic consumer goods industries.

Protection and Quotas:

Import quotas are another instrument used to check free trade. Import quotas refer to the maximum quantities of goods which may be permitted to be imported during any period of time. They are also referred to as quantitative restrictions on imports. Quotas are more effective method of reducing trade than tariffs. A given commodity may be imported in a relatively large quantity despite high tariffs but low quotas totally stop the imports of a commodity beyond the fixed quota of the commodity. Since international negotiations to reduce trade barriers have tended to focus on tariffs, the various countries have resorted to non-tariff barriers to free trade. Let us now discuss below the effects of quotas.

Since quota limits the imports of a commodity, it reduces supply of a commodity in a country as compared to the case with a free trade. Like tariffs, quotas raise the prices of imported goods and encourage domestic production of those goods. But in case of quotas, the government does not collect any revenue. Quotas may be imposed against imports from all countries or used against the imports of only a few countries.

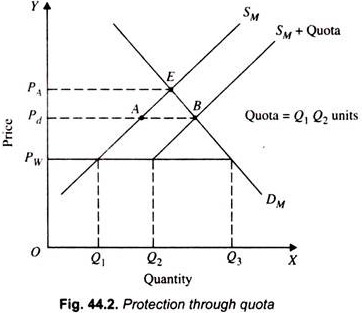

Economic effects of quota are graphically shown in Fig. 44.2 where DM and SM are domestic demand and supply curves of a commodity respectively. In the absence of trade, price of the commodity in the country is PA. Suppose the world price of the product is Pw. Under free trade, at price Pw of the commodity the domestic producers of the country will produce OQ1, quantity but as domestic demand of the product at price Pw is OQ3, the quantity Q1 Q3 represents the imports at the world price Pw.

Now assume that the Government imposes a quota and fixes the quantity of the product equal to Q1Q2 to be imported. With this the total supply of the product in the domestic market will be away from the domestic supply SM equal to the distance Q1 Q2. Incorporating the quota equal to Q1 Q2 we draw a new supply curve SM+ Quota, which lies to the right of the domestic supply curve SM in the absence of trade. It will be seen from Fig. 44.2 that interaction of the supply curve (SM+ Quota) with the domestic demand curve DM determines price Pd which is higher than the world price Pw.

It will be seen from Fig. 44.2 that difference AB between demand and domestic supply at price Pd is exactly equal to the fixed quota of Q1 Q2 quantity of imports. It is thus dear that, like tariffs, fixation of quota has served to protect the domestic industry and raise price. It will therefore have same effects as we have explained in case of tariff. It may however be noted that, unlike tariff, in case of quota Government would not collect any revenue.