These causes of increasing and decreasing returns to scale are often classified according to whether they are internal or external to the firm. The internal factors are usually subject to a certain amount of managerial control, whereas the external factors are not.

Internal economies and diseconomies are those conditions that bring about decreases or increases in a firm’s long-run average costs or scale of operations as a result of size adjustments within the firm. Internal economies are those advantages which are enjoyed by a particular firm and not by others in an industry. An obvious example is better utilisation of factory space or of by-products or improved efficiency in the use of resources.

They occur regardless of adjustments within the industry and are due mainly to physical economies or diseconomies. Thus, reductions in long-run average costs occur largely because the indivisibility of productive factors is overcome when size and output are increased; on the other hand, increases in long-run average costs occur because of adverse interaction between management and other resources.

These economies are of five main kinds:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) Technical economies,

(b) Managerial economies,

(c) Financial economies,

(d) Marketing economies, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(e) Risk-bearing economies.

External economies and diseconomies are those conditions that bring about decreases or increases in a firm’s long-run average costs or scale of operations as a result of factors that are entirely external to and beyond the control of the firm. They depend on adjustments of the industry and are related to the firm only to that extent that it is part of the industry.

External economies result from the simultaneous growth or interaction of a number of firms in the same or related industries and arise due to the localisation of an industry in a particular area. These are available to all firms in the industry no matter what their size. An increase in prices of raw materials caused by a simultaneous expansion by all firms is an example of external diseconomy. For these reasons there is a feeling that small is beautiful.

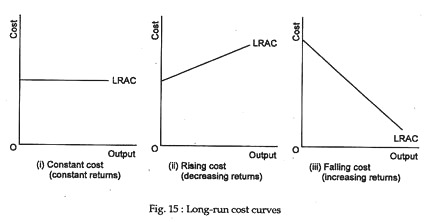

Panel A of Fig. 15 shows a long-run average cost curve for a firm of this type. In other cases, economies of scale are extremely important. Even after the efficiency of management begins to decline, technological economies of scale may offset the diseconomies over a wide range of output. Thus, the LRAC curve may not turn upward until a very large volume of output is attained. This case (typified by the so-called natural monopolies) is illustrated in Panel B of Fig. 15.

In many actual situations, however, neither of these extremes describes the behaviour of LRAC. A very modest scale of operation may enable a firm to capture all of the economies of scale and diseconomies may not be incurred until the volume of output is very great. In this case, LRAC would have a long horizontal section as shown in Panel C of Fig. 15. Some economists and business executives feel that this type of LRAC curve describes many production processes.