Let us make an in-depth study of business organization in an economy.

Meaning of Business Organisation:

Business means a production unit or firm.

A firm is a decision-making production unit which transforms resources into goods and services which are ultimately bought by consumers.

Plant is a production unit in the industry where the firm is the unit of ownership and control.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Traditional economic theory has assumed that the typical firm has a single objective — to maximise its profits. The modern theories of the firm, however, do acknowledge that firms may have other objectives, such as sales-revenue maximisation or the maximisation of managerial utility and so on.

Economists have pointed out that the owners of a large company place the effective control of the company in the hands of professional managers. The interests of the owners and the managers may diverge. The owners (shareholders) are interested in obtaining the maximum dividend possible over a reasonable time period, which means that the firm should aim to maximise its long-run profits.

The managers, who, mostly, do not have share in the profits, may not have maximisation as their primary objectives. Instead, they may aim for an increased market share or greater sales revenue which will bring them more prestige or a higher salary. They cannot completely forget about profit because they need to earn a satisfactory level of profit in order to keep the shareholders satisfied.

We assume here that firms have the single objective of profit-maximisation. A firm has to decide what level of output to produce. This decision will, in turn, determine the firm’s purchase of factor inputs and may also influence the price at which its output can be sold. As society developed from feudalism to capitalism, so the form of business organisation evolved.

Types of Business Units:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We now consider the legal status of the different types of firms. The earliest forms were the Sole-traders and the partnership. The joint-stock company did not become common until the 19th century.

A Sole Trader:

One-person business or a sole trader is the most common type of firm. This is a business owned by a single individual who is fully entitled to the income of the business and is fully responsible for any losses the business suffers.

As this business is small, it can provide personal service to its customers and can respond flexibly to the requirement of the market. Decisions can be taken quickly as the owner does not require to consult anybody.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Disadvantages with this business are that the owner cannot specialise in particular functions but must be a jack-of-all trade, and that the finance is limited to that which the owner himself can raise. Another disadvantage is that there is no distinction between the owner and his business.

The owner has unlimited liability for any debts incurred by the business, so that in the event of a bankruptcy all his assets are liable to seizure. This type of businesses are common in retailing, farming, personal services, etc.

Partnership:

The logical progression from one-man business is partnership. A partnership contains from two to twenty partners who jointly own a business, sharing profits and being jointly responsible for any losses. The main advantages of partnership are that more finance is likely to be available and each partner may specialise to some extent.

The major disadvantage is that of unlimited liability. Partnerships are often found in the professions — for example, among doctors, dentists, solicitors. The disadvantage of unlimited liability lead to the growth of the joint-stock companies.

Joint-Stock Company:

The joint-stock company with limited liability developed in the second half of the 19th century. It had started long ago, e.g. the East India Company was incorporated 400 years ago in 1600 and dissolved in 1874 — after a life-span of 274 years! It helped to promote the development of large companies by providing a relatively safe vehicle for investment in industry and commerce.

The liability of the shareholders is limited to the amount they have subscribed to the firm’s capital. Unlike a partnership, it has a legal existence distinct from that of its owners. To make information available to potential shareholders, joint-stock companies are required to submit details of profits, turnover, assets, etc. to the Registrar of Companies.

A joint-stock company can either be a private limited company or public limited company. The shares of the private company may not be offered for sale on the stock exchange. Private companies require a minimum of two and maximum of fifty shareholders.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The shares of a public company can be offered for sale to the public. A public company requires a minimum of seven shareholders, but there is no upper limit. Shares can be resold in the stock exchange to anyone prepared to pay the going price. Trading in the stock exchange, reported in most daily newspapers, is primarily the sale and resale of existing shares in public companies.

Companies are run by board of directors. The board of directors makes decisions about how the firm is run but must submit an annual report to the shareholders. At the annual general meeting, the shareholders can vote to sack the directors, each shareholder having as many votes as the number of shares owned. Companies are the main form of organisation of big business. Majority of companies are public limited companies.

Cooperatives:

In the U.K., consumers’ cooperatives have been relatively successful since the first cooperative was formed at Rochdale in 1844. There are about 13 million members of the cooperative societies in the U.K. Producers’ cooperative, on the other hand, who have not been successful and are not particularly significant in the U.K.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Public Corporation:

The public corporation is a form of business organisation that has developed in the U.K. for those areas where the government has decided to place business in the hands of the state.

Whilst there are early examples of the formation of public corporation, such as the port of London Authority (1909) and the British Broadcasting Corporation (1927), most were formed in the period of the post-war Labour Governments of 1945-51. The public corporations are run by the Board of Directors (BoD) appointed by the government.

Financing of Firms:

The money, a firm raises for carrying on its business is called its financial capital or real capital. There are two basic types of financial capital used by firm’s owner’s capital and debt.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Owner’s Capital:

In proprietorships and partnerships, one or more owners will put up much of the required funds. A joint-stock company acquires funds from its owners by selling stocks and shares to them. These are basically ownership certificates. Profits that are paid out to shareholders are called dividends.

One easy way for an established firm to raise money is to retain current profits rather than paying them out to shareholders. Financing from undistributed profits has become an important source of funds in modem times. Reinvested profits add to the value of the firm and raise the market value of existing shares.

Debt:

Holders of debentures are the firm’s creditors, not its owners. They have loaned money in return for what is called a debenture. This is a promise both to pay a stated sum each year and to repay the loan at some stated time in the future.

The amount that is paid each year is called the interest, while the amount of the loan that will be repaid at some future specified date is called the principal. The time at which the principal is repaid is called the redemption date.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In economic theory, the term bond is used to refer to any piece of paper that provides evidence of a debt carrying a legal obligation to pay interest and repay the principal at some future date. Henceforth, we refer to debt instruments as bonds.

Growth of Firms:

A firm may have several motives for growth. Some firms see expansion as a way of ensuring their survival in the long-run. Diversification may similarly be seen as a key to survival and the best prospect for growth. The diversification of the Imperial Tobacco Group into areas such as food production, packaging, educational supplies is a case in point.

Another possible motive for growth is to achieve higher profits. These may result, first, from the likely fall in unit production costs as the firm expands and, second, through the firm’s increase in its market shares and, therefore, its ability to control the price of its product. A firm with a dominant position in a market may be acknowledged by other firms as a price leader.

How Firms Grow:

A firm can grow as a result of internal or external growth. Internal growth occurs when a single firm expands its scale of operation within its present management structure. This process would be easier if the markets for the firm’s product are expanding rapidly and if the firm is efficient relative to its competitors.

The raising of finance may be a constraint on the speed at which a firm can grow. However, there are various sources of finance the firm can explore plough back some retained profits, borrow funds from financial institutions and float a new share issue, etc.

External growth occurs when two or more firms join together to form a large firm. This may result in a takeover of one firm by another. Alternatively, two or more firms may agree to a merger to form a new company. We can classify the integration of firms into three categories vertical, horizontal and conglomerate.

Vertical Integration:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This occurs when two or more firms in the same industry, but at different stages in the production process, join together. Most of the major oil companies, for example, do not confine their interests to oil refining they are also involved in the exploration and extraction of oil (vertical backward integration) and they own chains of filling stations (vertical forward integration).

Vertical Backward Integration:

This occurs when a firm acquires another firm which produces at an earlier stage of the production process. Example includes the acquisition of tea plantations by tea companies.

Motives are Simple:

Security of vital supplies or control over the quantity of raw material and to have control over a competitive advantage over other companies.

Vertical Forward Integration:

This occurs when a firm acquires another firm which produces at a stage of the production process nearer the consumer.

Example:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Purchase of a rolling mill by a steel producer.

Horizontal Integration:

This refers to the combining of firms that produce at a similar stage of industry’s production. Examples include the mergers between British Motor Holdings and Leyland Motors to form British Leyland in 1968. Horizontal integration may be undertaken to achieve economies of scale — that is, to reduce AC of production or to carry out the rationalisation of capacity.

If two companies have excess capacity, they may be able to close some plants and still be able to meet the market demand. In practice, economies of scale and rationalisation may prove difficult to achieve through horizontal integration.

Conglomerate Mergers:

These take place between firms whose activities are not directly related. Thus, the possibility of achieving economies of scale is not so great as in the case of horizontal integration. The main justification for a conglomerate merger might be that it has the effect of replacing an inefficient management by a more efficient one.

This might lead to more efficient use of company’s assets. Because of the difficulty of achieving economies of scale and because conglomerate mergers lead to increased concentration in the ownership of resources, the case for conglomerate mergers does not appear to be very strong.

Production:

We develop a theory about the behaviour of a producer. This is known as the theory of the firm. How do owners of businesses react to changing taxes, changing input prices, and changing government regulations? In order to answer these questions, we have to understand the nature of production costs and revenues for each firm. Here we examine the nature and type of production.

Defining a Business:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Business means production unit or firm. There is a difference between a corporate giant like Coca-Cola and the local dress shop. We will only make a distinction between these types of firms, in so far as they exercise their market powers and control the prices of commodities they sell.

Types of Business Ownership:

The Firm:

A firm is an organisation that brings together different factors of production, such as labour, land and capital, to produce a product or service which it is hoped, can be sold for a profit. The actual size of a firm would affect its precise structure, but a common set-up would involves entrepreneur, manager, and workers.

The entrepreneur is the person who takes the risks. Because of this, the entrepreneur also decides who to hire to run the firm. The true quality of an entrepreneur depends on his ability to pick good managers.

Managers are the ones who decide who should be hired and fired and how the business should be set up. The workers are the ones who use the machine to produce the products that are being sold by the firm. Workers and managers are paid contractual wages. However, entrepreneurs are not paid contractual wages. They receive what is left after all expenses are paid.

Profits are the reward paid to the entrepreneurs for taking risk:

Profit:

TR – TC, when TR = Total Revenue and TC = Total Costs.

The costs of production should include an element of profit to pay for entrepreneur’s service.

Normal Profit:

The minimum level of reward required to ensure that existing entrepreneurs are prepared to remain in their present area of production which is included in the cost of production; as it is an essential minimum reward necessary to keep them into the present economic activity.

It includes all costs including opportunity cost of using entrepreneur’s own resources:

Economic Profits = Total Revenue minus Total Opportunity Cost of all inputs used.

The economic profit involves allocation of resources and also their cost accounting calculations.

Opportunity Cost of Capital or Imputed Costs of Using Producer’s Own Capital:

Firms enter or remain in an industry if they earn, at a minimum, a normal rate of return or profit. This means that people will not invest their capital unless they receive a competitive rate of return. Any business wishing to attract capital must at least pay the same rate of return on that capital as all other businesses of similar risk are willing to pay.

For example, if individuals can invest their capital in almost any publishing firm and get a rate of return of 10% per annum, then each firm in the publishing industry must expect to pay 10% as the normal rate of return to present and future investors.

This 10% is the cost of capital which is known as the opportunity cost of capital. This opportunity cost of capital is the amount of income or yield, forgone by giving up an investment in another firm.

Capital will leave firms or industries where the expected rate of return falls below its opportunity cost which is the cost of using something in a particular venture as the benefit forgone by (or opportunity cost of) not using it in its best alternative use.

Opportunity Cost of Labour/Imputed Costs of Using Own Labour:

Sole-traders often exaggerate their profit rates because they forget about the opportunity cost of their labour. For example, sole-traders calculate their profits by adding up all their sales revenue and subtracting all their costs excluding the opportunity cost of their own labour. The end-result they will call profit. However, they will not include into their costs the salary that they could have earned if they had worked for somebody else in a similar type of job. This is the opportunity cost of their labour.

We have discussed only the opportunity cost of capital and labour, but we could have discussed about the opportunity cost of all inputs. Whatever the inputs may be, its opportunity cost must be taken into account in order to calculate true economic profits.

Another way of looking at the opportunity cost of running a business is that opportunity cost consists of all explicit (direct) and implicit (indirect) costs. Accountants are only able to take account of explicit costs. Therefore, accounting profits end up being the residual after only explicit costs are subtracted from total revenue.

Accounting Profits are not equal to Economic Profits:

The term ‘profits’ in economics means the income that entrepreneurs earn over and above their own opportunity cost of labour, capital etc. Profits can be regarded as total revenue minus total costs — this is accounting profits — but economists must include all costs, including opportunity costs.

Goal of Firm:

The firm’s goal is to maximise profit. It is expected to make the positive difference between total revenue and total cost as large as it can. We use a profit-maximising model because it allows us to analyse a firm’s behaviour with respect to quantity supplied and the relationship between cost and output.

However, the prime goal of some firms may not be to maximise profits but rather to maximise sales revenue or maximisation of managerial utility and the prestige of the owners. Thus, provided the assumption of profit-maximisation is correct for most firms, the model will suffice as a good starting-point.

Company — Organization Legally Allowed to Produce and Trade:

Unlike a partnership, it-has a legal existence distinct from that of its owners. Ownership is divided among shareholders. The original shareholders may now have sold shares to outsiders. By selling entitlements to share in the profits, the business can raise new funds.

Shareholders earn a return in two ways. First, the company makes regular dividend payments, paying out to shareholders the part of the profits that firm does not wish to reinvest in the business. Second, the shareholders may make capital gains (or losses).

Shareholders of a company have limited liability. The most they can lose is the money they spent buying shares. Unlike Sole-traders and partners, shareholders cannot’ be forced to sell their personal possessions if the business goes bust. At worst, the shares become worthless.

Companies are run by boards of directors who submit an annual report to shareholders who can vote to sack the directors if it seems that they are not running it well. Companies are the main form of organization of big business.

A Firm’s Accounts:

Firms report two sets of accounts, one for stock and one for flows. Stocks are measured at a point in time, flows are corresponding measures during a period of time. A firm reports profit and loss accounts per year (flow accounts) and a balance sheet showing assets and liabilities at a point in time (stock accounts).

The inflow from the tap changes the stock of water over time, even though the stock is in litres at each point in time. We begin with flow accounts.

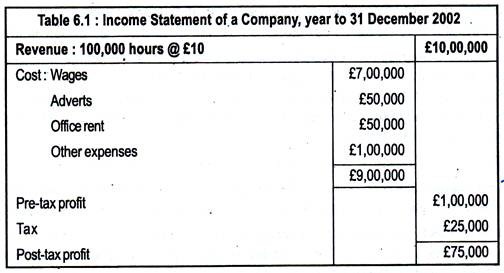

Flow Accounts:

Revenue is what the firm earns from selling goods and services in a given period, cost is the expenses incurred in production in that period and profit is the difference between total revenue and total cost.

Unpaid Bills:

People do not always pay bills on time. At the end of 2002, the company has unpaid bills. Nor has it paid all its own bills. From an economic point of view, the right definition of revenue and costs relates to the activities during the year whether or not payments have yet been made.

A firm’s cash flow is the net amount of money actually received during the period. Actual payments and receipts thus may differ from economy’s revenue and cost. Profitable firms may still have poor cash flow, for example, when customers are slow to pay.

Capital and Depreciation:

Many firms do buy physical capital. Physical capitals are machinery, building, equipment used in production. Capital means goods not entirely used up in the production process during the period. For example, buildings, Lorries, etc. are capital goods to be used in the next year.

Electricity is not capital goods purchases in 2002 do not service into 2003. Economists also use durable goods and physical assets to describe capital goods.

How is the cost of a capital good treated in calculating profit and cost? It is the cost of using rather than buying capital equipment that is paid for of the firm’s costs within the year. Suppose a company buys 6 computers for £1,000 each. £6,000 is not the cost of computers in calculating costs and profits for that year.

Rather, the cost is the fall in value over the year. Suppose wear-and-tear and obsolescence which reduce the value of the computer by £200 during the year. Part of the economic cost of using computers over the year is £1,200 by which they depreciate during the year.

Depreciation is the loss in value of a capital good during the period. Depreciation makes economic profit and cash flow differ. Depreciation is an economic cost since the resale value of goods falls steadily. Cash flow may now be higher than economic profit.

Inventories:

If production is instantaneous, firms can produce to meet orders as they arise. In fact, production takes time. Finns hold inventories to meet future demand. Inventories are goods held in stock by the firm for future sales.

Suppose in 2002 Rover make 1 million new cars and sells 9, 50,000. By December its stock of finished cars is 50,000. What about profit? Revenue arises from selling 9, 50,000 cars. Should cost reflect sales of 9, 50,000 cars or the 1 million it actually made?

Economic costs relate to the 9, 50,000 cars actually sold.

Borrowing:

The interest on borrowed money is the part of the cost of doing business and should be counted as part of the costs.

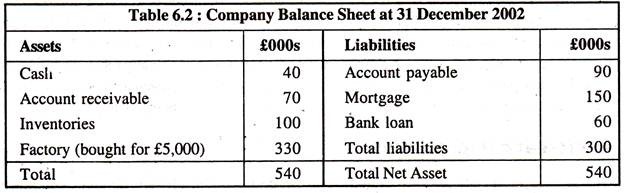

Stock Account:

The Balance Sheet:

The income statement of Table 6.1 shows flows in a given year. We can also examine the firm at a point in time, the result of all its past trading operations. The balance sheet lists the asset the firm owns and the liabilities for which it is responsible at a point in time. Table 6.2 shows the balance sheet.

A firm’s net worth is the assets it owns minus the liabilities it owes. Company assets are cash in the bank, money owed by its customers (account receivable), inventories in its warehouse and its factory (original cost £5, 00,000 now worth only £3, 30,000 because of depreciation). The total value of assets is £5, 90,000.

Company’s liabilities are bills it has yet to pay, the mortgage on its factory, and a bank loans for short terms cash needs. Its total liabilities (debts) are £3, 00,000. The net worth of the company is £2, 40,000. Its assets minus liabilities.

You make a takeover bid for the company. Should you bid £2, 40,000, its net worth? Probably even more, if it is a live company with good prospects and a proven record. You get not only its physical and financial assets minus its liabilities but also its reputation or goodwill. If it is a sound company bid more than £2, 40,000.

Alternatively, you may think its accountants undervalued the resale value of its assets. If you can buy the company for £2, 40,000 you make a profit by selling off the separate pieces of capital, a practice known as asset-stripping.

Earnings:

When a firm makes a profits after tax, it can pay them out to shareholders as dividends, or keep them in the firm as retained earnings.

Retained Earnings are the part of after-tax profits ploughed back into the business.

Retained earnings increase the net worth of the business.

Opportunity Cost and Accounting Costs:

Economists and accountants take different views of cost and profit. An accountant is interested in tracking the actual receipts and payments. An economist is interested in how revenue and cost affect the firm’s supply decision, the allocation of resources in particular activities. Accounting methods can mislead in two ways opportunity cost is the amount lost by not using a resource in its best alternative use.

Supernormal profit is pure economic profit and measuring all economic costs properly (including the opportunity cost of your own labour and capital). The key to supernormal profits are true indicator of how well you are doing by tying-up your time and funds in the business. Supernormal profits are not accounting profits, which give the incentive to shift resources into a business.

Firms and Profit-Maximisation:

Economists assume that firms choose output to maximise profits. Some economists and business executives question this assumption. A Sole-trader may prefer to work for herself even if she could earn more in working somewhere else. Her business decisions reflect maximisation of satisfaction not her monetary profit alone.

Ownership and Control:

A most significant reason to question profit maximisation is that large firm is run not by its owners but by a board of directors. At the annual general meeting, shareholders may dismiss the board. The directors have all information at their disposal; it is hard for the shareholders to know that different directors would be able to make more profits.

Economists call this a separation of ownership and control. Although shareholders want the maximum possible profit, the directors can pursue different objectives. Do directors have an incentive to act other than in the interest of the shareholders?

Directors may aim for size and growth rather than maximum possible profit, spending a large sum of money for a costly advertisement to boost sales. Nevertheless, there are two reasons why the aim of profit maximisation is a good thing to begin with. Even if the shareholders cannot recognize that profits that they are earning at the moment are the best possible one.

If profits are lower, share prices will also be low. By mounting a takeover, another company can buy the shares cheaply, sack the existing managers, restore profit-maximisation-policies and make a handsome capital gain as the share price rises once the stock market sees the improvement in profits. Fear of takeover may induce the directors to try to maximise profits.

Moreover, shareholders may try to ensure that the interests of the directors and shareholders coincide. By giving senior directors big bonuses tied to profitability or share performance — shareholders try to make senior directors care about profits as much as shareholders do. The assumption that firms try to maximise profit is more robust than might first be imagined.

Corporate Finance and Corporate Control:

Corporate finance refers to how firms finance their activities sources of finance include:

(a) Borrowing from banks,

(b) Borrowing by selling corporate bonds whereby the firm promises to pay interest for a specific period and eventually repay the debt,

(c) Using stock market to sell new shares of the firm. Different countries have different system of corporate finance.

Finance or Control:

Large firms finance most of their new investment from their retained profits. Roughly 85 to 90% of UK corporate investment is financed in this way, less than 70% comes from sales of new shares on the stock market. The key difference lies not in the ease with which they provide firms with finance, but in the way they award control rights to those providing that finance.

Corporate control refers to who controls the firm in different situations. In the bank-based insider system (Japan and continental Europe), representatives of the bank sit on the firm’s board, using this inside position to press for changes when mistakes are made. The market- based system (USA and UK) entails a small role for banks, and a large role for stock-markets and debt-markets.

Failure to make interest payments on debt usually give debt-holders the right to make firm bankrupt, a radical transfer of corporate control in which existing management rarely survives.

Similarly, the existence of publicly quoted shares raise the possibility of a stock market takeover in which a new management team effectively buys control on the open market. Outsider, in market-based systems of corporate finance thus become markets for corporate control itself.

Hostile Takeover:

Some economists believe hostile bids as a vital force for efficiency. However, the separation of ownership and control in public companies leads to a principal-agent problem. The agents (i.e. the managers) are tempted to act in their own interests rather than those of their principals (the shareholders).

A principal or owner may delegate decisions to an agent. If it is costly to monitor the agent, the agent has inside information about its own performance, causing a principal-agent problem.

The threat of a hostile takeover deters managers from departing too much from the profit-maximisation principles that shareholders want. Slack management leads to low profits, depress share prices, and opportunities for takeover raiders to buy company cheaply. The threat of takeover provides a discipline that helps to overcome the principal-agent problem.

However, hostile takeovers also undermine the existing managers. Wanting workforce cooperation in moving to new production methods, you promise to reward employees well once the productivity has risen. The workers know you keep your words, but cannot trust you.

While the changes are being made, profits may temporarily fall and you face a takeover raid. The new owner may fire workers to save money. So your workers reject your plan to bring sensible change to the company.

Hostile takeover sometimes inhibit investment and encourage short-termism. However, the German and Japanese system insider systems also have their problems, especially if radical action is required. The Japanese economy is languished in the doldrums over the 1990s mainly because its companies fail to make key changes after a property price collapse in the early 1990s.

In the USA and the UK, there would have been less patience, less concern about admitting failure, and a swifter response.

Firm’s Decision to Supply:

To maximise profits the firm chooses the best level of output. Changing output affects both the costs of production as well as revenue from sales. Costs and demand conditions jointly determine the output choice of a profit-maximising firm.

Cost-Minimisation:

The firm wishes to make its chosen output level at the least possible cost. Otherwise, by producing the same output at lower cost it could increase profit. Thus, a profit-maximising firm must produce its chosen output as cheaply as possible.

The Total Cost Curve:

The total cost increases with increase in output. At high levels of output, cost rises sharply as output increases. Total revenue is a function of price and quantity demanded. At a price of £15 the firm sells say 2 units and thus the total revenue is £30. The lower the price, the more it sells: its demand curve slopes down.

Profit:

Total revenue minus total cost. Maximum profit means the difference between total revenue and total cost must be highest. Or, MR = MC which will maximise profit as well, at a point where MC is rising.

MC is the rise in total cost as output increases by one unit. Similarly, MR is the rise in total revenue when output (or sale of output) rises by one unit.

If MR is greater than MC, the firm should raise output. Producing and selling an extra unit adds more to total revenue than to total cost, thus raising total profit. If, on the other hand, MR is less than MC, the extra unit of output reduces total profit.

Thus we can use MC and MR to calculate the output that maximises profit. So long as MR is greater than MC, keep output increasing. As soon as MR = MC, stop increasing output. When MC is greater than MR do not increase output.

Once we reach MR = MC, any increase in output will reduce MR steadily for two reasons: one, because demand curve slopes down, the extra unit of output can only be sold at lower prices, and second, successive price reductions reduce the revenue earned from existing units of output, and, at a larger output, there are more existing units on which revenue is lost when price fall further.

To sum up:

(a) MR falls as output rises and

(b) MR is less than the price for which the last unit is sold, because lower price reduces revenue earned from existing output.

MR, MC and Output Choice:

MC = MR gives the profit-maximising output. When MR is greater than MC, expand output. If MR is less than MC, contract output. If the firm does not make profits when MC = MR, it may be better to close down altogether.

The Firm’s Output Choice: Marginal condition – Output Decision – Check

MR > MC – Raise

MR < MC – Cut

MR = MC – No change

If profits are positive, make output. If negative, quit the industry.

MC, MR Determine the Firm’s output: MC, MR

The MR and MC schedules are changing smoothly. The firm’s optimum output is Q1, MR > MC, and the firm should increase output. Where output is greater than Q1, MR < MC and profits are increased by reducing output. If the firm is losing money at Q1 it has to check whether it might be better not to produce at all.