Take the case of a small lake that one firm used for waste disposal and another for water supply. On deeper thought we are led to a more fundamental question: which one of the firms is really causing damage and which firm is the one suffering damages? This may sound counter intuitive as the natural answer would be that the waste disposing firm is of course the one causing the damage.

However it can be argued that the presence of the food processing firm inflicts damages on the waste disposing firm because its presence makes it necessary for the latter to take special efforts to control its emissions.

The problem may come about simply because it is not clear who has the initial right to use the services of the lake, that is, who effectively owns the property rights to the lake. When a resource has no owner, nobody has a strong incentive to see to it that it is not over exploited or degraded in quality.

Private property rights are, of course, the dominant institutional arrangement in most developed economies of the West. Developing countries are also now moving in that direction. There exists a familiarity with the operation of that institutional system when it comes to person made assets such as machines, buildings, and consumer goods. Private property in land is also a familiar arrangement.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If somebody owns a piece of land, he has an incentive to see to it that the land is managed in ways that maximise its value. If somebody comes along and threatens to dump something onto the land, the owner may call upon the law to prevent it if he wants to. By this diagnosis, the problem of the misuse of many environmental assets come about because of imperfectly specified property in those assets.

Principle:

Consider again the case of the lake and the two firms. Apparently there are two choices for vesting ownership of the lake. It could be owned either by the polluting firm or by the firm using it for water supply. How does this choice affect the level of pollution in the lake? Would it not lead to zero emissions if owned by the one firm and uncontrolled emissions if owned by the other?

Not necessarily, if owners and non-owners are allowed to negotiate. This being the very essence of a property rights system. The owner decides how the asset is to be used and may stop any unauthorized use, but may also negotiate with any-body else who wants to access that asset.

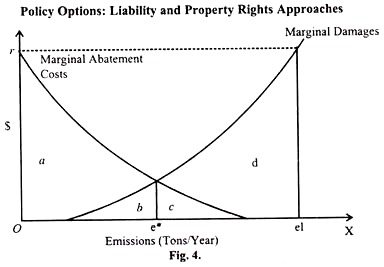

Consider fig. 4. Suppose the marginal damage function refers to all the damages suffered by the brewery – call this firm A. Assume the marginal abatement cost curve applied to the firm emitting effluent into the lake – call this one firm B.

Certain assumption have to be made with respect to the ownership of the lake. Theoretically the same quantity of emissions will result in either case, provided that the two firms can come together and strike a bargain about how the lake is to be used.

In the first case suppose that firm B owns the lake. Firm B may then use the lake any way it wishes. Suppose that emissions are initially at el. Firm B is initially devoting no resources at all to emissions abatement. But is this where matters will remain? At this point marginal damages are $r, whereas marginal abatement costs are nil.

The straightforward thing for firm A to do, therefor, is to offer firm B some amount of money to reduce its effluent streams. For the first ton any amount agreed on between 0 and $r would make both parties better off.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In fact they could continue to bargain over the marginal unit as long as marginal abatement costs. Firm B would be better off by reducing emissions for any payment in exceed marginal abatement costs, firm B would be better off by reducing emissions for any payment in excess of its marginal abatement costs, whereas any payment less than the marginal damages would make firm A better off.

In this way, bargaining between the owners of the lake (here firm B) and the people who are damaged by pollution would result in a reduction in effluent to e*, the point at which marginal abatement costs and marginal damages are equal.

Suppose, on the other hand, that ownership of the lake is vested in firm A, the firm that is damaged by pollution. In this case we might assume that the owners would allow no infringement of their property, that is, that the emission level would be zero or close to it.

Question is if this would be where it would remain. Not if again, owners and others negotiate. In this case firm B would have to buy permission from firm A to place its wastes in the lake.

Any price for this lower than marginal abatement costs but higher than marginal damages would make both parties better off. And so, by a similar process of bargaining with, of course, payments now going in the opposite direction, the emissions level into the lake would be adjusted from the low level where it started toward the efficient level e*.

At this point any further adjustment would stop because marginal abatement costs, the maximum the polluters would pay for the right to emit one more ton of effluent, are equal to marginal damages, the minimum firm A would take in order to allow firm B to emit this added ton.

So, we have seen in this example, if property rights over the environment asset are clearly defined, and bargaining among owners and prospective users is allowed, the efficient level of effluent will result irrespective of who was initially given the property right. In fact this illustrates a famous theorem, “Coase Theorem” after the economist Ronald. H. Coase a Nobel laureate in the year 1991.

Assumptions of the Coase Theorem:

Assume a world in which some producers and consumers subjected to externalities generated by other producers and consumers. Further assume,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Everyone has perfect information

2. Consumers and Producers are price takers

3. There is cost less court system for enforcing agreements

4. Consumers maximize utility and producers maximize profit

ADVERTISEMENTS:

5. There are no incomes or wealth or effects

6. No transaction costs

In this case, the initial assignment of property rights regulating externalities does not matter for efficiency. If any of these conditions does not hold well the initial assignment of rights does matter. Thus, in Coase Theorem, the optimal environmental allocation is independent of the distribution of property rights.

The wider implication is that by defining private property rights (not necessarily individual property rights because private groups of people could have these rights), conditions by which decentralized bargaining produce efficient levels of environmental quality can be defined. This has some appeal.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The advantage being that people doing the bargaining may know more about the relative values involved – abatement costs and damages – than anybody else, so there is some hope that the true efficiency point will be arrived at.

Also, because it would be a decentralized system there would be no need for a central bureaucratic organization making decisions that are based mostly on political considerations instead of the true economic values involved. Ideas like this have lead some people to recommend widespread conversion of natural and environmental resources to private ownership as a means of achieving their efficient use.

Conditions:

In practice of course, for a property rights approach to work right certain pre requisites need be fulfilled, essentially four main,

(i) Property rights must be well defined, enforceable, and transferable.

(ii) Transaction costs should be at a minimum

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) There must be a reasonably efficient and competitive system for interested parties to come together and negotiate about how these environmental property rights will be used.

(iv) There must be a complete set of markets so those private owners may capture all social values associated with the use an environmental asset.

If firm A cannot keep firm B from doing whatever the latter wishes, of course a property rights approach will not work. In other words, owners must be physically and legally able to stop others from encroaching on their property. Owners must be able to sell their property to any would-be buyer. This is especially important in environmental assets.

If owners cannot sell their property, it will weaken their incentives to preserve its long run productivity. This is because any use that does draw down its long run environmental productivity cannot be punished through the reduced market value of the asset.

Many economists have argued that this is a particularly strong problem in developing countries; because ownership rights in these settings are often ‘accentuated’ and people do not have strong incentives to see that long run productivity is maintained.