Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Economic Growth’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Economic Growth’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Economic Growth

Essay Contents:

- Introduction to Economic Growth

- Adam Smith and Economic Growth

- The Classical Theory of Economic Stagnation

- Marx’s Theory of Economic Development

- Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth

- Vicious Circle Theory of Economic Growth

- Balanced Vs. Unbalanced Economic Growth

- Underdevelopment as Coordination Failure

- The Lewis Model of Economic Growth

- The Fei-Ranis Modification of Lewis Model of Economic Growth

- Baran’s Neo-Marxist Thesis

- Dependency Theory of Economic Growth

- The New (Endogenous) Economic Growth Theory

Essay # 1. Introduction to Economic Growth:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Various theories, viewpoints and models have been presented from time to time to account for the sources of economic growth and the determinants of economic development. To most people, a theory is a contention that is impractical and has no factual support.

For the economist, however, a theory is a systematic explanation of interrelationships among economic variables and its purpose is to explain causal relationships among these variables. Usually a theory is used not only to understand the world better but also to provide a basis for policy. This essay discusses a few of the major theories of economic development, from which emerged alternative approaches to economic development.

The earliest students of development economics were the mercantilists. Mercantilists were a group of traders. They believed that exports were always good for a country because exports implied inflow of precious metals (such as gold and silver). By contrast, imports were harmful for a country because imports implied outflow of precious metals. So, in their view, growth and development of a nation depended on its accumulation of precious metals.

Essay # 2. Adam Smith and Economic Growth:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The mercantilist view was challenged by Adam Smith (1723-1790), the Father of Economics, in 1776. Smith, in his Wealth of Nations, pointed out that the mercantilist view contained a major fallacy. International trade is just like a two-person zero-sum game in which one country’s gains is the other country’s loss. So two trading nations cannot have trade surplus (or favourable balance of trade) at the same time. In the late 18th century Smith argued that the true wealth of a nation is not its accumulated gold and silver hut its labour power— the human factor of production.

And the wealth of nation depended on two main factors:

(i) The productivity of labour, and

(ii) The proportion of productive labour in the total labour force (i.e., the labour force participation rate).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Smith believed that division of labour, specialisation, and exchange were the true springs of economic growth.

Smith argued that in a market-based (competitive) economy, with no collusion, cartel or monopoly, each individual, by acting in his (her) own interest, promoted the public interest. A producer who charges more than others will not find buyers, a worker who asks more than the going wages will not get job, and an employer who pays less than the market wage (i.e., the wages competitors pay) will not find anyone to work.

It was as if an invisible hand were behind the self-interest of capitalists, merchants, landlords and workers, directing their actions toward maximum economic growth. So Smith advocated a laissez-faire (non-interference of government in economic matters) and free trade policy as two growth-promoting measures.

Essay # 3. The Classical Theory of Economic Stagnation:

The classical theory, based on the work of David Ricardo (1772-1823), had a pessimistic view about the possibility of sustained economic growth. For Ricardo, who assumed little continuing technical progress, growth was limited by scarcity of land. A major tenet of Ricardo was the law of diminishing returns.

For him, diminishing returns due to population growth and a fixed supply of land threatened economic growth. Since Ricardo believed that technical change or improved production techniques could only temporarily avert the operation of the law of diminishing returns, increasing capital was seen as the only way to offset this long-run threat.

However, any fall in the rate of capital accumulation would lead to eventual stagnation. Ricardian stagnation might result in a Marxian scenario, in which wages and investment would be maintained only if property were confiscated by society and payments to private capitalists and landlords stopped.

Essay # 4. Marx’s Theory of Economic Development:

Marx (1818-83) predicted that the capitalist system would in the initial stage grow due to increased profit (surplus value which was the result of exploitation of labour) and would provide funds for accumulation. But since wages were pegged at the subsistence level, due to the existence of a huge reserve army of unemployed, the capitalists would suffer from a realisation crisis. They would not be able to realise the profits embodied in already produced goods. And, according to Marx, the under consumption of the masses is the root cause of all crises.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Marx, in fact, made certain predictions about the growth, maturity and stagnation of capitalism. He predicted that the capitalist system would ultimately collapse for want of markets and would yield place to socialism.

Unfortunately, history has not obliged Marx. The year 1989 saw the collapse of socialism (especially in erstwhile USSR and its satellite countries) and with it the abandonment of the centralised planning system and the emergence of newborn post-socialist countries.

All these countries have embraced the market system which is now thought to be a more efficient mechanism for solving society’s economic problems, promoting faster economic growth and improving the living standards of the people.

Essay # 5. Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

By criticizing Marx’s stages of growth, viz, feudalism, capitalism and socialism, Walter W. Rostow sets forth a new historical synthesis about the beginnings of modern economic growth on six continents.

His economic stages are:

(i) The traditional society,

(ii) The preconditions for takeoff,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) The takeoff,

(iv) The drive to maturity, and

(v) The age of high mass consumption.

The most important stage is the third one, i.e., the takeoff stage. In order to reach that stage a country must save and invest at least 10 -12% of its national income. Many Western countries had already reached the stage when Rostow’s book appeared. Many underdeveloped countries reached the stage later (mainly under the influence of planning).

Essay # 6. Vicious Circle Theory of Economic Growth:

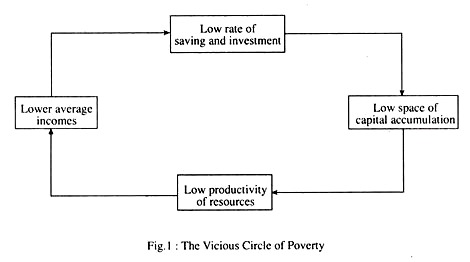

The vicious circle theory presented by Ragnar Nurkse in his book- The Problems of Capital Formation in Underdeveloped Countries, 1953) indicates that poverty perpetuates itself in mutually reinforcing vicious circles on both the supply and demand sides. In fact, low per capita income is both the cause and the effect of poverty.

A. Supply Side:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At low levels of income, people cannot save much. Shortage of capital leads to low productivity of labour, which perpetuates low levels of income. Thus the circle is complete, as shown in Fig. 1. A country is poor because it was previously so poor that it could not save and invest. Or, as Jeffrey Sachs (2005) explains the poverty trap: ‘Poverty itself is the cause of economic stagnation.’

In short, various obstacles to development are self-enforcing. Low levels of income prevent saving, retard capital growth, hinder productivity growth and keep income low. Successful development may require taking steps to break the chain at various points. By contrast, as countries get richer they save more, creating a virtuous circle in which high sayings rates lead to faster growth. A country is rich because it was rich in the past. Or a rich country is likely to become richer in the future.

B. Demand Side:

In addition, due to the narrow size of the domestic market for light consumer goods (such as shoes, textiles, radio, etc.) there is hardly any incentives for potential entrepreneurs to investment. Lack of invest means low factor productivity and continued low income. A country is poor because it was so poor in the past that it could not provide the market to spur investment.

Essay # 7. Balanced Vs. Unbalanced Economic Growth:

A major debate in the areas of development economics from the 1940s through the 1960s concerned balanced growth versus unbalanced growth. The term balanced growth has been used in different senses. The meaning of the term may vary from the absurd requirement that all sectors grow at the same rate to the more sensible plan that a minimum attention has to be given to all major sectors—industry, agriculture, and services.

Balanced Growth:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The main advocate of the doctrine of balanced growth was Nurkse. To him, balanced growth means the synchronized application of capital to a wide range of different industries. Nurkse considers this strategy as the only escape route from the vicious circle of poverty (underdevelopment).

Big Push Thesis:

The advocates of the Nurkseian doctrine support the big push thesis, arguing that a strategy of gradualism is bound to fail. A substantial effort is needed to overcome the inertia inherent in a stagnant economy. According to Paul N. Rosenstein-Rodan (1943), the factors that contribute to economic growth—such as demand and investment in infrastructure—do not increase smoothly but are subject to sizable jumps or indivisibilities. These indivisibilies result from flows created in the investment market by external economies (positive externalities), that is, cost advantages enjoyed by one firm due to output expansion by another firm.

These benefits spillover to society as a whole, or to some members of it, rather than to the investor concerned. This means that the social profitability of this investment exceeds its private profitability. Furthermore, unless the government intervenes, total private investment will be grossly inadequate compared to society’s needs.

Indivisibility in Infrastructure:

For Rosenstein-Rodan, a major indivisibility is in infrastructure, such as power, transport and communications. This basic social capital reduces costs to other industries.

Indivisibility in Demand:

The indivisibility arises from the interdependence of investment decisions; that is, a prospective investor is uncertain whether the output from his investment projects will find a market. This problem can be solved if a number of industries are set up so that new producers become each other’s customers and create additional markets through increased incomes. Complementary demand reduces the risk of not finding a market. Reducing interdependent risks increases the incentive to invest.

Hirschman’s Strategy of Unbalanced Growth:

A. O. Hirschman develops (1958) the idea of unbalanced investment to complement existing imbalances. In his view, deliberately unbalancing the economy, in line with a predesigned strategy, is the best path for economic growth. He argues that the big push theory cannot be applied to less developed countries (LDCs) because they do not have the skills needed to launch such a massive effort. The scarcest resource in LDCs is the decision-making input, i.e., entrepreneurship, not capital. Economic development is held in check not by shortage of savings, but by that of risk-takers and decision-makers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Hischman’s view, low-income countries need a development strategy that spurs investment decisions. He suggests that since physical resources and managerial skills and abilities are scarce in LDCs, a big push is sensible only in strategically selected industries within the economy. Growth is then likely to spread from one sector to another (similar to Rostow’s concept of leading and lagging sectors).

However, it is not in the Tightness of things to leave investment decisions solely to individual entrepreneurs in the market. The reason is that the profitability of different investment projects may depend on the order in which they are undertaken. For example, the return from a car factory may be 12%, and that from a steel plant 10%. However, if the car factory is set up first, its return is likely to be low due to shortage of steel.

However, if the steel plant is set up, the returns to the car factory may increase in the next period from 12 to 15%. This means that society would be better off investing in the steel plant first and the car factory next, rather than making independent decisions based on the market. So planners and policy-makers need to consider the interdependence of one investment project with another so that they maximise overall social profitability.

They need to make that investment which promotes the maximum investment. Investment should be concentrated in those industries which have the strongest linkages—both backward (to enterprises that sell inputs to the industry) and forward (to units that buy output from the industry).

The steel industry, for instance, may be accorded the maximum priority by the planners because it has backward linkages with coal and iron ore industries, and forward linkages with car and engineering industries. So there is need for making public investment in steel industry which has a strong investment potential in the sense that it is likely to spur private investment. Similarly, public investment in power and transport will increase productivity and thus encourage investment in various other industries.

Critique of Unbalanced Growth:

One main drawback of unbalanced growth approach is that it fails to stress the importance of agricultural investments. According to Hirschman, agriculture does not stimulate linkage formation so directly as other industries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, empirical studies indicate that agriculture has substantial linkages to other sectors. Moreover, as Johnston and Mellor have pointed out, agricultural growth makes vital contributions to the non-agricultural sector through increased food supplies, added foreign exchange, labour supply, capital transfer and wider markets.

The truth is that there is no conflict between these two strategies of development. An optimum strategy must combine some elements of balance as well as imbalance. As E. Wayne Nafziger has opined- ‘What constitutes the proper investment balance among sectors requires careful analysis. In some instances, imbalances may be essential for compensating for existing imbalances. By contrast, Hirschman’s unbalanced growth should have some kind of balance as an ultimate aim.’

Essay # 8. Underdevelopment as Coordination Failure:

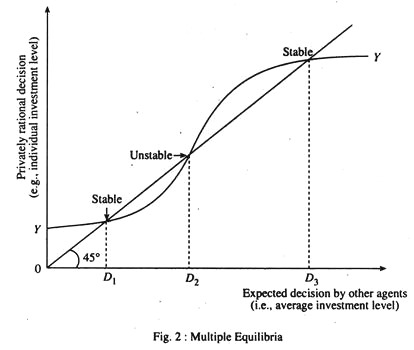

To some modern economists underdevelopment is result of coordination failure. This is why the theory of big push or critical minimum effort or balanced growth has been put forward. The coordination failure problem leads to multiple equilibria, as has been suggested by M. P. Todaro.

The basic point is that benefits an economic agent receives from taking an action depends positively on how many other agents are expected to take the same action or the extent of these actions. For example, price a farmer can expect to receive for his output depends on the number of intermediaries who are active in channel of distribution which, in turn, depends on number of other farmers who specialise in the same product.

Likewise, fertility decision need in effect to be coordinated across families. All are better if average fertility rate declines. But any one family may be worse off by being only one to have fewer children. The reason is that in rural areas children are a source of labour power for agricultural families. So if only one family adopts the small family norm it will have to hire workers from the external labour market by paying higher wages.

In Fig. 2 the S-shaped privately rational decision function YY first increase at a increasing rate and the at a decreasing rate.

This shape reflects typical nature of complementariness. For example, some economic agents may take complementary action such investing even if others in the economy do not, particularly when interactions are expected through foreigners, say, through exporting. If in this case one or a few agents take action, each agent may be isolated from others. So spillovers may be minimum.

Thus the curve YY does not rise quickly at first as more agents take the decision to invest. But after enough invest there may be a cumulative effect, in which most agents begin to provide external benefits to neighbouring agents and the curve rises at a much faster rate. Finally, after most potential investors have been seriously affected and most important gains have been realised the curve starts to rise at a decreasing rate.

In Fig. 2 function YY cuts the 45° line three times. Thus there is possibility of multiple equilibria. Of these D1 and D3 are stable equilibria. The reason is that if expectations were slightly changed to a little above or below these-levels economic agents (investors) would adjust their behaviour in such a way as to bring the economy back to equilibrium levels. In each case YY function cuts 45° line from above. This is the hallmark of a stable equilibrium.

The intermediate equilibrium at D2 cuts YY function from below. So it is unstable. This is because if a few less entrepreneurs were expected to invest equilibrium would be D1 and if a few more, equilibrium would shift to D3.

Therefore, D2 may be treated as chance equilibrium, i.e., it could be an equilibrium only by chance. Thus in practice we can think of an unstable equilibrium such as a D2 as ways of dividing ranges of expectations over which a higher or lower stable equilibrium will hold sway.

Thus there is need for coordinating investment decisions when the value (rate of relation) of one investment depends on the presence or the extent of other investments. All are better off with more investors or higher rate of investment.

But this cannot be achieved only through market system. So there is need for government intervention. It is possible to achieve the desired outcome only under the influence of certain types of government policies. Difficulties of investment coordination give rise to government-led strategies for industrialisation.

Technology Spillover:

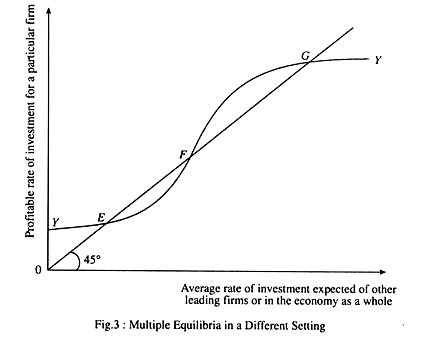

The investment coordination perspective explains the nature and extent of problems posed when technology has spread effects, i.e., development of technology by one firm has favourable effects on other firms, i.e., positive externality.

Now suppose we show average rate of investment expected of other key firms or in the economy as a whole on the horizontal axis or profitable rate of investment for a particular firm on the vertical axis, given what other firms are expected to invest on average. In this case points where the YY the curve crosses 45° line in Fig. 2 depict equilibrium investment rates.

Then due to direct relation between investment and growth, the economy may get struck in a low growth rate largely because its expected rate of investment is likely to be low. Changing expectations may not be sufficient if it is more profitable for a firm to wait for others to invest rather than to take the lead and become a ‘pioneer’ investor. In that case there is need for government policy in addition to a change of expectation of investors.

This is why attention to the presence of multiple equilibria is so important. Market forces can bring us to one of these equilibria but they are not sufficient to ensure that no equilibrium will be achieved and they offer no mechanism to move from a bad equilibrium to a good one.

In general when jointly profitable investment may not be made without coordination multiple equilibria may exist in which the same individuals with access to same resources and technologies could find themselves in either a good or bad situation. For example, the extent of effort of each firm in a developing region puts to increase the rate of technological transfer depends on effort put by other firms.

No doubt bring in modern technology from abroad often has spillover effects for other firms. But the presence of multiple equilibria subject to making better technology available is a necessary but not a sufficient condition to achieve faster economic growth and consequent improvement in the living standards of the people.

Essay # 9. The Lewis Model of Economic Growth:

In the Lewis model, economic growth occurs due to an increase in the size of the industrial sector, which accumulates capital, relative to the subsistence agricultural sector, which does not accumulate any capital. The source of capital in the industrial sector is profits from the low wages paid in unlimited supply of surplus labour from traditional agriculture. An unlimited supply of labour available to the industrial sector facilitates capital accumulation and economic growth.

Urban industrialists increase their labour supply by attracting workers from agriculture who migrate to urban areas when wages there exceed rural wages. Lewis elaborates this point while explaining labour transfer from agricultural to industry in a newly industrializing country. Industrial expansion would come to a halt when labour shortages develop in rural areas.

The significance of the Lewis model is that growth takes place as a result of structural change. An economy consisting mainly of a subsistence agricultural sector (which does not save) is transformed into one predominantly in the modern capitalist sector (which alone saves). As the relative size of the capitalist sector grows, the ratio of profits and other surplus to national income grows.

Essay # 10. The Fei-Ranis Modification of Lewis Model of Economic Growth:

In John Fei and Gustav Ranis, in their modification of the Lewis model, contend that the agricultural sector must grow, through technical progress, for output to grow as fast as population; technical change increases output per hectare to compensate for the growing pressure of labour on land, which is a fixed resource. As with the Lewis model, the advent of fully commercialized agriculture and industry ends industrial growth (or what Fei-Ranis calls the take-off into self-sustained growth).

Essay # 11. Baran’s Neo-Marxist Thesis:

Paul A. Baran incorporated Lenin’s concepts of imperialism and international class conflict into his theory of economic growth and stagnation. For Baran LDCs were unlikely to achieve growth and development because of Western economic and political domination, especially in the colonial period.

Capitalism arose not through the growth of small competitive firms at home but through the transfer from abroad of advanced monopolistic business. Baran felt that as capitalism took hold, the bourgeoisie (business and middle classes) in LDCs, lacking the strength to spearhead thorough institutional change for major capital accumulation, would have to seek allies among other classes.

From Marxian perspective Baran writes:

What is decisive is that economic development in underdeveloped countries is profoundly inimical to the dominant interests in the advanced capitalist countries. The backward world has always represented the indispensable hinterland of the highly developed capitalist West.

The only way out of the impasse may be worker and peasant revolution, expropriating land and capital, and establishing a new regime based on collective effort and the creed of the predominance of interests of society over the interests of a selected few.

Essay # 12. Dependency Theory of Economic Growth:

According to A. G. Frank, a major dependency theorist, underdevelopment is not simply non-development, but is a unique type of socioeconomic structure that results from the dependency of the underdeveloped country on advanced capitalist countries.

This results from foreign capital removing a surplus from the dependent economy to the advanced country by structuring the underdeveloped economy in an ‘external orientation’ that includes the export of primary products, the import of manufactures, and dependent industrialisation. As Frank states- ‘It is capitalism, world and national, which produced under development in the past and still generates underdevelopment in the present.’

Frank’s dependency approach maintains that countries become underdeveloped through integration into, not isolation from, the international capitalist system. However, despite some evidence supporting Frank, he does not give adequately demonstration that withdrawing from the capitalist system results in faster economic development.

Unequal Exchange:

According to dependency theorists, the same process of capitalism that brought development to the presently advanced capitalists countries resulted in the underdevelopment of the dependent periphery. The global system is such that the development of part of the system occurs at the expense of other parts. Underdevelopment of the periphery is the Siamese twin of development of the centre.

Centre-periphery trade is characterised by unequal exchange. This may refer to deterioration in the peripheral country’s terms of trade. It may also refer to unequal bargaining power in investment, transfer of technology, taxation, and relations with multinational corporations. According to S. Amin, unequal exchange means the exchange of products whose production involves wage differentials greater than those of productivity.

The Neoclassical Counterrevolution:

The neoclassical counterrevolution to Marxian and dependency theory emphasised reliance on the market, private initiative, and deregulation in LDCs. Neoclassical growth theory emphasised the importance of increased saving and capital formation for economic development and for empirical measures of sources of growth. The neoclassical model predicts that incomes per capita between rich and poor countries will converge. But empirical studies do not support this prediction.

This is why N. G. Mankiw and others propose an augmented Solow neoclassical model which includes human capital as an additional explanatory variable to physical capital and labour. The Washington institutions of the World Bank, IMF, and US Government have applied neoclassical analysis in their policy-based lending to LDCs.

Essay # 13. The New (Endogenous) Economic Growth Theory:

The new (endogenous) growth theory developed by Paul Romer arose from concerns that neoclassical economists neglected the explanations of technical change and accepted the unrealistic assumption of perfect competition. For Mankiw, Romer, and Weil, human capital and for Romer, endogenous (originating internally) technology, when added to physical capital and labour in neoclassical growth theory, are important factors contributing to economic growth.

One reason is that although there are diminishing returns to physical capital, there are constant returns to all (human and physical) capital. The new growth theory, however, does no better than an enhanced neoclassical model in measuring the sources of economic growth.