Here is an essay on ‘Trade and Economic Growth’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Trade and Economic Growth’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay # 1. Trade and Economic Growth in the 20th Century:

The development process during the 20th century was characterized by two distinct phases— the periods before and after 1950. During the first half of 20th century, the growth process was disrupted by two world wars. During the inter-war period occurred the Great Depression. A number of years were taken by the world economy to recover from it. Many countries suffered enormous damage due to war and the productive activity remained greatly disrupted.

As a consequence, economic growth was very slow and discontinuous. The index of world trade during the 20th century could increase from 100 to just 131 between 1913 and 1950. The growth rate of foreign trade on the average per decade in this period was only 6.9 percent. During the decade (1928-1938), the world output could grow at the rate of barely 1 percent essentially because of the global depression and the resultant protectionist policies followed by a large number of countries.

In the latter half of the 20th century, there had been the co-existence of rapid economic growth and rapid expansion in world trade. That re-emphasized the notion of ‘trade as engine of growth’. In respect of the developed market economies, the average annual growth rate of real GDP at current prices during 1950-60, 1960-70 and 1970-74 periods were 4.1, 5.1 and 4.2 percent and the per capita real product in these countries over the same periods grew respectively at the rates of 2.8, 4.1 and 3.2 percent.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The average annual growth rates of volume of exports for these countries during these periods were 8.6, 11.6 and 10.0 percent respectively. The share of developed market economy countries in 1960, 1970 and 1974 stood at 66.8 percent, 71.9 percent and 65.5 percent. It is thus clear that the latter half of the 20th century reflected a definite and strong association between high rate of expansion of domestic output and a high rate of growth of world trade.

In the case of the LDC’s, the picture was significantly different and pessimistic. The foreign trade had hardly a worthwhile propulsive role for the economic growth in these countries. At the best, expansion of trade kept pace with the growth of national income. In the case of developing countries, the average annual growth rates of real GDP during 1950-60, 1960-70 and 1970-74 periods were 4.7, 5.2 and 6.4 percent and average annual growth rates of per capita real product were 2.4, 2.6 and 3.8 percent respectively.

Even though their rates of growth stand well in comparison to those of the developed countries, the things were quite depressing in the matter of their foreign trade. During the periods indicated above the average annual growth rate of their exports were 5.2, 6.0 and 4.8 percent and their share in the world export, except the OPEC producers continued to decline.

In case of the LDC’s of Asia, the share out of world exports had not only remained extremely low, it had also shown a declining trend. In 1960, 1970 and 1974, their share in the world exports was just 1.6 percent, 0.8 percent and 0.7 percent respectively. The share of LDC’s including the oil-exporting countries declined in the world exports from 33.8 percent in 1928 to 25.2 percent in 1974. Their share in world imports marked a decline from 28 percent to 17.8 percent during this period. If oil-exporting countries were excluded, the picture was much bleaker.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Their share in world exports between 1928 and 1974 fell from 32.2 percent to 10.3 percent. In case of imports, their share had fallen from 26.9 percent to 13.8 percent in 1974. From the above data, it is very clear that the growth of world trade had not been commensurate with the growth of their GDP. Except OPEC group, which experienced tremendous expansion in their foreign trade and growth, the other LDC’s found that trade had not acted as an engine of growth for them.

An important feature of international trade in the 20th century was that the major part of world trade had been the trade among the developed countries themselves. It is true that their trade with LDC’s was not insignificant, yet its value was less than 28 percent of the total external trade of the advanced countries. The trade and economic policies of developed countries were essentially geared to promote trade and other economic relations with the developed world.

In the case of LDC’s the reverse was true. The trade with industrial countries was more important for them than the trade among themselves. The desired co-operation was never available from the advanced countries. They were not keen to permit the products of the LDC’s to have access to their markets. Such an attitude clearly had serious implications both for the growth and trade of the developing countries.

Another aspect of international trade of LDC’s was concerned with their terms of trade vis-a-vis the developed world. The LDC’s predominantly exported primary products and imported manufactured products. The writers like Singer (1950) and Prebisch (1964) have forcefully explained that there had been deterioration in the terms of trade (measured by ratio of export prices to import prices) for the LCD’s.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Leaving aside the boom between 1971 and 1974, the purchasing power of primary exports, except oil had declined. Since 1960, on the average, the barter terms of trade had been unfavourable for the non-oil exporting countries.

Apart from their small share in world trade and adverse terms of trade, the LDC’s had very little competitive power because of their technological inferiority and insufficient purchasing power in their domestic markets. The balance of payment deficits persisted in these counties and they were forced to impose import-restricting measures, which in the final analysis had adverse impact upon development in general and the growth of exports in particular.

Jagdish Bhagwati recognised the conflict between trade and development in the LDC’s under the case of ‘immiserising growth’. He demonstrated that the technological progress in the primary production could lower prices by a measure enough to outweigh any gain due to rise in real income. The international specialisation, in fact, transferred the gains from trade and development to the advanced countries rather than the poor countries.

This conflict between trade and growth in the LDC’s led them to adopt inward-looking trade policies or protectionist policies during 1960’s, 1970’s and early 1980’s. It is only through such policies that they expected to off-set the backwash effects of trade and the risks associated with having all their eggs in single primary commodity basket. Since the mid-1980’s, there had been increasing pressure from the advanced countries and the international financial institutions to dismantle the protectionist trade policies.

The adoption of free trade could undoubtedly cause some increase in their volume of international trade but at the tremendous cost of slowing down the industrialisation and diversification of domestic production and exports. The insistence of advanced countries and the international lending institutions about the abandonment of protectionist policies by the LDC’s is unjustified, when they themselves are raising tariff walls by organising regional economic groupings.

Essay # 2. Economic Growth and Terms of Trade:

An attempt was made to indicate how the terms of trade of the home country get affected due to combined production and consumption effects. In the present section, the impact of growth reflected through changes in the demand for imports of the growing country upon its terms of trade will be analysed on the assumption that the international price ratio of exportable commodity (X) and importable commodity (Y) remains the same.

The terms of trade measured by the ratio of quantity imported (QM) to the quantity exported (QX), will deteriorate, remain unchanged or improve, when the demand for imports increases, decreases or remains unchanged. These situations can be explained through Figs. 11.4. (i), (ii) and (iii).

In Fig. 11.4. (i), (ii) and (iii), the production possibility curve of the home country A is originally AA1. As growth takes place, the production possibility curve shifts to the right to A2A3. Since the international prices of X and Y commodities remain the same, the international exchange ratio lines T1 and T2 have the same slope or these are parallel to each other.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Fig. 11.4 (i), the production equilibrium shifts from the original position P to P1 after growth takes place. The consumption equilibrium, determined by the tangency of international exchange ratio line (T1) and the community indifference curve I1 takes place originally at C. After growth, the tangency between T2 and I2 takes place at C1. Thus the consumption equilibrium shifts from C to C1 after growth occurs. If PP1 is parallel to CC1, the ratio of QM to QX will remain the same. It follows that the growth leaves the terms of trade of the growing home economy unchanged.

In Fig. 11.4., (ii) the original production and consumption equilibria occur at P and C respectively. After there is expansion in country A, the production equilibrium shifts from P to P1 and the consumption equilibrium shifts to the right of C to C1. In this case the rate of increase of exports is more than that of demand for imports resulting in an improvement in the terms of trade for the home country.

In Fig. 11.4., (iii), the growth results in the movement of production of equilibrium from P to P1 and consumption equilibrium from C to C1. In this case, since the domestic production of exportable commodity increases at a lesser rate than the increase in the demand for importable commodity, the terms of trade get worsened for the growing home country.

The above figures show that growth brings about an increase in the productive capacity and welfare of the people in the home country, though its effect on terms of trade may be varied— unfavourable, unchanged and favourable.

Essay # 3. Economic Growth and Trade in a Large Country:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The trading countries may differ on account of their relative size. A large trading country is likely to have the power or capacity to affect the relative commodity prices at which it trades. In the present section, an attempt will be made to study the way in which growth will affect production, welfare and terms of trade in the relatively large country.

The process of growth can create two types of effects upon a trading country—wealth effect and terms of trade effect. The wealth effect refers to a change in the output per worker or per head of population. If the wealth effect is positive, it signifies an increase in nation’s welfare. Otherwise there can be the possibility of a decline in welfare or its remaining unchanged.

The terms of trade effect is concerned with the effect of international trade, subsequent to growth, upon the terms of trade of the country. If growth causes an expansion in country’s volume of trade at constant prices, the terms of its trade tend to deteriorate. On the contrary, if growth reduces the volume of trade of the country, there is a tendency towards the improvement in its terms of trade.

If growth and trade result in a positive wealth effect and improvement in terms of trade, there is a definite increase in the welfare of the nation. On the opposite, if both wealth effect and terms of trade effect are unfavourable, there is a definite reduction in the welfare of the country. In case, the two effects move in the opposite direction, the nation’s welfare may increase, decrease or remain unaffected depending upon their relative magnitudes

ADVERTISEMENTS:

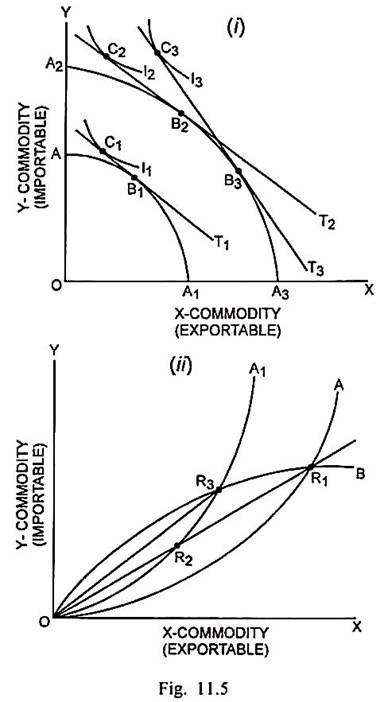

If the growth involves increased supply of scarce factor (say, capital), in the large country A, there will be favourable wealth effect and terms of trade effect and trade will be beneficial for this country. It is shown through Fig. 11.5. (i) and (ii).

In Fig. 11.5. (i) the original production possibility curve is AA1. Given the international prices of two commodities, T1 is the terms of trade line and production equilibrium is determined at B1. The tangency of T1 with the community indifference curve I1 determines the consumption equilibrium at C1. If growth results in an increased supply of scarce factor capital, the production of capital- intensive importable commodity Y can increase proportionately more than that of commodity X so that the production possibility curve shifts to A2A3.

Given the same prices of two commodities, T2 is the terms of trade line. The production and consumption equilibria are determined at B2 and C2 respectively. Thus given the constant prices, the wealth effect is positive and consumption also takes place at a higher commodity indifference curve I2. That signifies an increase in welfare.

In case of this large country, change in factor endowments raises the price of exportable commodity and lowers the price of importable commodity so that the terms of trade line T1 becomes more steep than T2. In this case, the production equilibrium is at B3 and consumption equilibrium takes place at C3 upon a still higher community indifference curve I3. Thus there is increase in both aggregate production and welfare.

The effect upon the terms of trade of large country is explained through Fig. 11.5. (ii). Originally OA is the offer curve of the large home country A and OB is the offer curve of foreign country B. The exchange takes place at R1 and the terms of trade are measured by the slope of the line OR1. As growth takes place, the offer curve of country A shifts to OA1. Given the constant prices of two commodities, exchange takes place at R2. It signifies a reduction in the volume of trade subsequent to growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If growth causes relative change in the prices of two commodities, the exchange takes place at R3 where the offer curves OA1 and OB intersect each other. The terms of trade are measured by the slope of more steep line OR3. It shows an improvement in the terms of trade for large country A. There is, however, still reduction in the total volume of trade. It is now clear that the wealth effect and terms of trade effect are both positive and growth is definitely beneficial for the large country. There is an increase in domestic output and welfare coupled with improvement in terms of trade, even though there is a contraction in the volume of trade.

In case, the growth process results in expansion in the supply of abundant factor, the wealth effect is likely to be negative. There will also be unfavourable terms of trade. Both these effects will reduce the welfare of the nation, even though volume of trade becomes larger.

Essay # 4. Economic Growth and Trade in a Small Country:

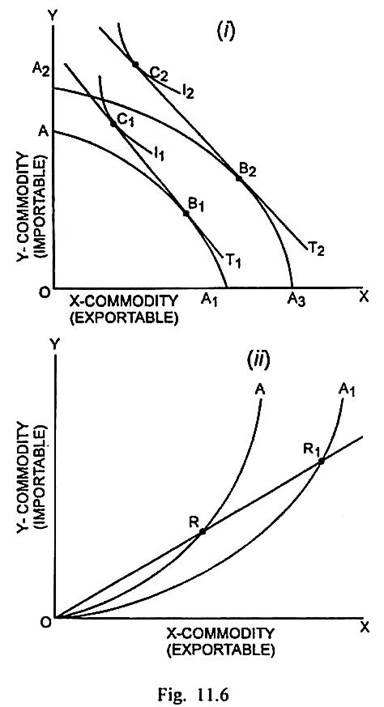

If the home country is labour-abundant and it is a small country, the growth expressed through the expansion in the supply of labour, may expand the domestic output in absolute terms as well as the volume of trade. This country may also achieve a higher level of welfare in absolute sense. In per capita terms, however, the welfare is likely to decrease. Since the country is small, it can have no impact on the relative prices of commodities and terms of trade remain unaffected. These effects may be shown with the help of Fig. 11.6. (i) and (ii).

In Fig. 11.6. (i), AA1 is the original production possibility curve and T1 is the terms of trade line. Production takes place at B1 and consumption at C1. If growth involves the increased supply of abundant factor labour, the production possibility curve shifts to A2A3. The production takes place at B2 where the terms of trade line T2, which is parallel to the original terms of trade line T1, is tangent to A2A3. The new terms of trade line has the same slope because a small country does not have the capacity to bring about a relative change in the commodity prices. Consumption takes place at C2 where T2 is tangent to the higher community indifference curve I2.

Thus growth results in an increase in both domestic output and welfare in the absolute sense. The new position of production equilibrium also implies an expansion in the volume of international trade. The increase in consumption at C2 is however, relatively less than the increase in the factor supply. It may mean a somewhat lower per head consumption than before and the welfare will possibly decline.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Fig. 11.6. (ii), originally R is the point of exchange and the slope of the line OR indicates the terms of trade. The growth causes a shift in the offer curve of this country to OA1. The terms of trade, however, remain the same because these are measured by the slope of line OR1 which coincides with OR. At the point R1, however, exchange involves larger quantities of both X and Y commodities than at R. It signifies an expansion in the volume of trade for this country even at the constant terms of trade.

Essay # 5. Trade—An Engine of Growth?

The entire Mercantilist emphasis on creation of trade surplus was based upon the assumption that trade surplus could stimulate the growth process in the exporting country. The classical writers like Adam Smith, David Ricardo and J.S. Mill fully acknowledged the benefits of international division of labour and specialisation upon the economies of the trading countries.

The economists like Haberler and Cairncross also believe that trade makes a substantial contribution to the development of both developed and the less developed countries. “It is trade”, said Cairncross, “that gives birth to the urge to develop, the knowledge and experience that make development possible, and the means to accomplish it.” It was in view of highly dynamic and powerful effects of trade on the whole process of growth that D.H. Robertson commented that trade had emerged as ‘an engine of growth.’

Growth-Stimulating Effects of Trade:

The major growth-inducing effects of trade, particularly from the viewpoint of less developed countries, are as under:

(i) Spread Effect:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The expansion of exports by a given country generates large export-earnings which lead to expansion not only of export industries in that country, but also several other complementary industries. The primary increase in output, income and employment brings about the secondary and tertiary increases in output, income and employment in several industries and sectors. Thus, trade creates a spread effect and ensures steady growth of the economy.

(ii) Expansion of Market:

A small size of market has a highly restrictive effect upon the growth process in a country. However, if the surplus produce in that country is disposed of in foreign markets, there is an expansion in the size of market. It has highly stimulating effect on the inducement to invest and to make scientific and technical innovations. Consequently, there is progressive enlargement of production frontiers in that country on account of foreign trade.

(iii) Optimum Use of Resources:

The expansion of international trade results in the international division of labour, specialisation, expansion in scale of production and elimination of wastages. Each trading country becomes able to make the optimum use of all available productive resources.

(iv) Increase in Capital Formation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The growth process in LDC’s remains inhibited because of persistent acute shortage of capital. The international trade provides large export earnings to the poor countries. In addition, trade stimulates the large inflows of foreign direct investment and portfolio investments. In this way, trade can help in increasing the rate of capital formation in LDC’s and can step up the rate of their growth.

(v) Diversification in Production:

When a country wants to cater to foreign markets, it will have to produce such commodities which are in accordance with tastes and preferences of the foreign consumers. It makes the exporting countries to produce diverse varieties of products. The diversification in production has a strong stimulating effect on the productive activities in the exporting countries.

(vi) Technological Development:

The urge to expand exports continuously makes the producers of the home country to make scientific and technical innovations. The improvement in techniques either through import of technology from abroad or through indigenous scientific and technical research gives a strong fillip to the process of growth.

(vii) Import of Development Goods:

The international trade permits the home producers to import raw materials, construction materials, semi-finished goods, machinery, equipment and advanced technical know-how from advanced countries. It enables the LDC’s to undertake industrialisation and to achieve a higher rate of economic growth.

(viii) Equalisation of Factor Prices:

The international product movements have the effect of bringing about an absolute and relative equalisation of factor prices which offsets any adverse effect of international immobility of factors upon growth.

(ix) Larger Tax Revenues:

The expansion of industrial activities in a developing country due to an increase in exports provides more tax revenues to the government of the home country from several direct and indirect taxes. The yield from import duties also increases. The availability of more tax revenues can enable the government to finance various projects of economic and social development.

(x) Off-Setting of BOP Deficit:

The LDC’s are faced with the serious problem of BOP deficit. The maximisation of exports of goods and services from the deficit country can have the effect of offsetting the balance of payments deficit.

(xi) Rise in Consumption Standard:

Through the import of consumable products, a LDC’s can easily wipe out the domestic shortages of essential consumer goods. In order to enlarge exports, the domestic production of consumable goods is also increased. In addition, the superior varieties of consumer goods can be imported from abroad. Thus there can be qualitative improvement of consumption standards in the LDC’s. It is a definite indicator of greater development.

(xii) Greater International Co-Operation:

The international trade generally increases the mutual dependence of both advanced and poor country. They fully recognise the mutuality of their economic, political and strategic interests. Consequently, there is a greater measure of economic and technological transfers from the advanced to the poor countries. Increased international co-operation can greatly accelerate the growth process in the LDC’s.

Adverse Effects of Trade on Growth:

The writers like Prebisch, Singer, Myint and Myrdal recognise that the international trade exerts serious pressures and strains upon the process of growth and, therefore, it is not appropriate to consider it as an engine of growth.

The adverse effects of trade upon economic growth of the LDC’s are as follows:

(i) Exports of Primary Products:

The exports from the LDC’s are mainly of the primary products. The demand for such products is less elastic in the advanced countries. Consequently, the return from exports to the LDC’s are quite low and the development programme cannot be financed through receipts from exports.

(ii) Limited Capacity to Export:

The LDC’s have very limited capacity to export on account of deficiency of capital, lack of technical know-how, low factor efficiency and lack of industrial and infrastructural development. Given a low capacity to exports, the export-led strategy of growth cannot be workable in these countries.

(iii) Unfavourable Terms of Trade:

Even though the LDC’s export a large proportion of their output, yet low prices of primary products relative to manufactured products have kept the terms of international trade historically against the LDC’s. According to Prebisch-Singer thesis, secular deterioration of the terms of trade has been a major impediment in their growth.

(iv) Persistent BOP Deficit:

Most of the LDC’s are faced with the persistently increasing deficit in BOP equilibrium. Exports generally tend to increase at a relatively lesser rate than their imports. So long as BOP deficit cannot be offset, the growth process is not likely to gain momentum.

(v) High External Debt Burden:

Despite large proportion of output of the LDC’s being exported to foreign countries, the burden of external debt upon them continues to increase. At present, 8 of the 10 most indebted countries of the world are less developed countries. So long as these countries cannot get out of critical debt situation, the process of growth is not likely to be speeded up.

(vi) Activities of Foreign Investors:

Even if it is recognised that expansion of exports can stimulate foreign investment, yet the attitude of foreign investors of general neglect of investment in capital goods industries and infrastructural development in the LDC’s, cannot be helpful in stimulating the process of growth.

(vii) Exploitation of Resources:

International trade has always resulted in the exploitation of exhaustible mineral resources, cheap labour and markets of the LDC’s at the hands of the advanced countries. Trade has historically brought about greater impoverishment of the developing countries and not growth.

(viii) Intense Competition:

The free international trade based on the principle of comparative cost advantage involved the LDC’s into intense competition with the developed countries. In this unequal competition, the LDC’s have been at serious disadvantage. It has blocked almost completely the industrialisation in the poor countries.

(ix) International Transmission of Fluctuations:

International trade and changes in exchange rates lead to the transmission of fluctuations from the advanced to the LDC’s. Thus trade imparts instability to the economies of the latter and does not promote stable and steady growth.

(x) Import-Substitution:

In view of the failure of the export-led strategy of growth, many a developing country took resort to the alternative strategy of import-substitution for stimulating industrial expansion and for narrowing down the BOP deficit.

Thus a strong economic opinion discounts the possibility of accelerated growth through trade. Sill it may be stated that trade can be an engine of growth, if the developed countries permit greater access to the products of LDC’s in their markets; allow more favourable terms of trade; and render liberal commodity, capital and technical assistance to them.