Read this essay to learn about World Trade Organization (WTO). After reading this essay you will learn about: 1. Introduction to World Trade Organization for International Business 2. Reasons to Join WTO for International Business 3. Functions 4. Decision Making 5. Organizational Structure 6. Principles of the Multilateral Trading System 7. The Deadlock 8. Ministerial Conferences and Other Details.

Essay on World Trade Organization Contents:

- Essay on the Introduction to World Trade Organization for International Business

- Essay on the Reasons to Join WTO for International Business

- Essay on the Functions of WTO

- Essay on Decision Making of WTO

- Essay on the Organizational Structure of the WTO

- Essay on the Principles of the Multilateral Trading System under the WTO

- Essay on the Deadlock in WTO Negotiations

- Essay on Ministerial Conferences under World Trade Organization (WTO)

- Essay on GATT/WTO System and Developing Countries

Essay # 1. Introduction to World Trade Organization for International Business:

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is the only international organization that deals with global rules of trade between nations. It provides a framework for conduct of international trade in goods and services. It lays down the rights and obligations of governments in the set of multilateral agreements.

In addition to goods and services, it also covers a wide range of issues related to international trade, such as protection of intellectual property rights and dispute settlement, and prescribes disciplines for governments in formulation of rules, procedures, and practices in these areas. Moreover, it also imposes discipline at the firm level in certain areas, such as export pricing at unusually low prices.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The basic objective of the rule-based system of international trade under the WTO is to ensure that international markets remain open and their access is not disrupted by the sudden and arbitrary imposition of import restrictions.

Under the Uruguay Round, the national governments of all the member countries have negotiated improved access to the markets of the member countries so as to enable business enterprises to convert trade concessions into new business opportunities.

The emerging legal systems not only confer benefits on manufacturing industries and business enterprises but also create rights in their favour. The WTO also covers areas of interest to international business firms, such as customs valuation, pre-shipment inspection services, and import licensing procedures, wherein the emphasis has been laid on transparency of the procedures so as to restrain their use as non-tariff barriers.

The agreements also stipulate rights of exporters and domestic procedures to initiate actions against dumping of foreign goods. An international business manager needs to develop a thorough understanding of the new opportunities and challenges of the multilateral trading system under the WTO.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The WTO came into existence on 1 January 1995 as a successor to the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Its genesis goes back to the post-Second- World-War period in the late 1940s when economies of most European countries and the US were greatly disrupted following the war and the great depression of the 1930s.

Consequently a United Nations Conference on Trade and Employment was convened at Havana in November 1947.

It led to an international agreement called Havana Charter to create an International Trade Organization (ITO), a specialized agency of the United Nations to handle the trade side of international economic cooperation.

The draft ITO charter was ambitious and extended beyond world trade discipline to rules on employment, commodity agreements, restrictive business practices, international investment, and services. However, the attempt to create the ITO was aborted as the US did not ratify it and other countries found it difficult to make it operational without US support.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The combined package of trade rules and tariff concessions negotiated and agreed by 23 countries out of 50 participating countries became known as General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT): an effort to salvage from the aborted attempt to create the ITO.

India was also a founder member of GATT, a multilateral treaty aimed at trade liberalization. GATT provided a multilateral forum during 1948-94 to discuss the trade problems and reduction of trade barriers.

World Trade Organization membership increased from 23 countries in 1947 to 123 countries by 1994. GATT remained a provisional agreement and organization throughout these 47 years and facilitated considerably, tariff reduction. During its existence from 1948 to 1994, average tariffs on manufactured goods in developed countries declined from about 40 per cent to a mere 4 per cent.

It was only during the Kennedy round of negotiations in 1964-67, that an anti-dumping agreement and a section of development under the GATT were introduced. The first major attempt to tackle non-tariff barriers was made during the Tokyo round. The eighth round of negotiations known as the Uruguay Round of 1986-94 was the most comprehensive of all and led to the creation of the WTO with a new set up of agreements.

Essay # 2. Reasons to Join WTO for International Business:

Despite the disciplinary framework for conduct of international trade under the WTO, countries across the world including the developing countries were in a rush to join the pack. The WTO has nearly 153 members, accounting for over 97 per cent of world trade. Presently, 34 governments hold observer status, out of which 31 are actively seeking accession, including large trading nations, such as Russia and Taiwan.

The major reasons for a country to join the WTO are:

i. Since each country needs to export its goods and services to receive foreign exchange for essential imports, such as capital goods, technology, fuel, and sometimes even food, it requires access to foreign markets. But countries require permission for making their goods and services enter foreign countries.

Thus countries need to have bilateral agreements with each other. By joining a multilateral framework like the WTO, the need to have individual bilateral agreements is obviated as the member countries are allowed to export and import goods and services among themselves.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. An individual country is unlikely to get a better deal in bilateral agreements than what it gets in a multilateral framework. It has been observed that developing countries had to commit to a greater degree to developed countries in bilateral agreements than what is required under the WTO.

iii. A country can learn from the experiences of other countries, being part of the community of countries and influence the decision-making process in the WTO.

iv. The WTO provides some protection against subjective actions of other countries by way of its dispute settlement system that works as an in-built mechanism for enforcement of rights and obligations of member countries.

v. It would be odd to remain out of WTO framework for conducting international trade that has been in existence for about six decades and accounts for over 97 per cent of world trade. It may even be viewed as suspicious by others.

Essay # 3. Functions of WTO:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The major function of the WTO is to ensure the flow of international trade as smoothly, predictably, and freely as possible. This is a multilateral trade organization aimed at evolving a liberalized trade regime under a rule-based system.

The basic functions of WTO are:

i. To facilitate the implementation, administration, and operation of trade agreements.

ii. To provide a forum for further negotiations among member countries on matters covered by the agreements as well as on new issues falling within its mandate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iii. Settlement of differences and disputes among its member countries.

iv. To carry out periodic reviews of the trade policies of its member countries.

v. To assist developing countries in trade policy issues, through technical assistance and training programmes.

vi. To cooperate with other international organizations.

Essay # 4. Decision Making of WTO:

WTO is a member-driven consensus-based organization. All major decisions in the WTO are made by its members as a whole, either by ministers who meet at least once every two years or by their ambassadors who meet regularly in Geneva.

A majority vote is also possible but it has never been used in the WTO and was extremely rare in the WTO’s predecessor, GATT. The WTO’s agreements have been ratified in all members’ parliaments. Unlike other international organizations, such as the World Bank and the IMF, in WTO, the power is not delegated to the board of directors or the organization’s head.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In view of the complexities involved in multilateral negotiations among 150 member countries with diverse resource capabilities, areas of special interest, and geo-political powers, decision-making through consensus is highly challenging.

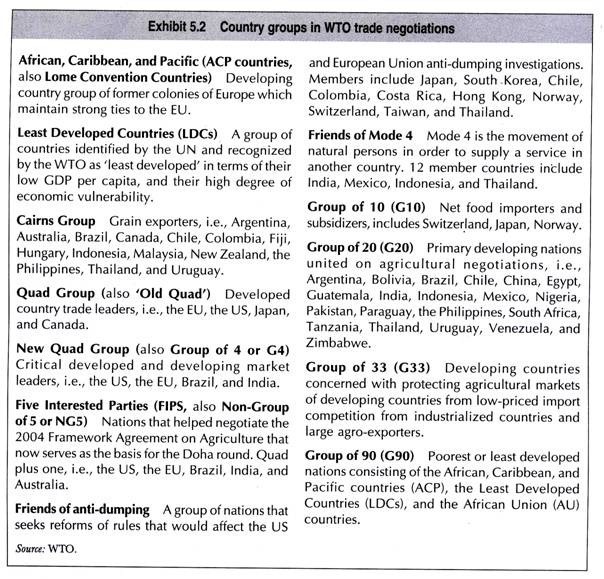

Developed countries with much greater economic and political strengths often employ pressure tactics over developing and least developed countries in building up a consensus. This has led to considerable networking among the member countries and evolving of several country groups as shown in Exhibit 5.2.

When WTO rules impose disciplines on countries’ policies, it is the outcome of negotiations among WTO members. The rules are enforced by the members themselves under agreed procedures that they negotiated, including the possibility of trade sanctions. The sanctions too are imposed by member countries, and authorized by the membership as a whole.

Essay # 5. Organizational Structure of the WTO:

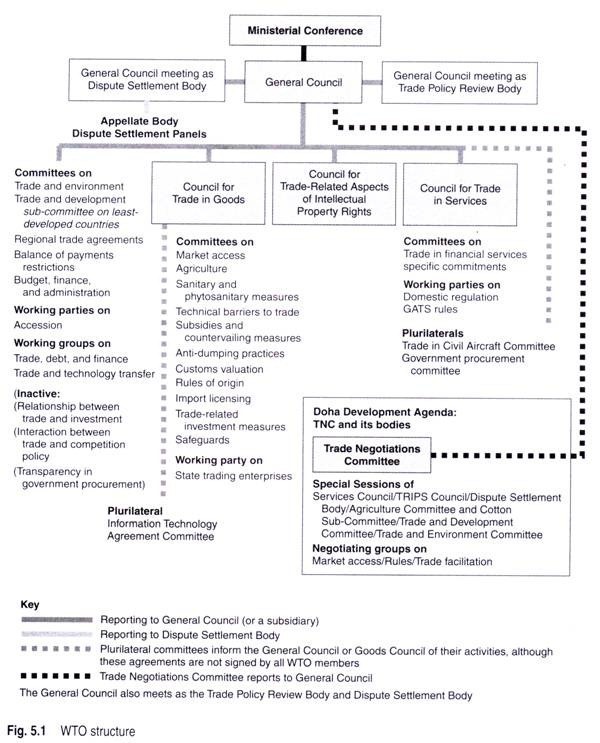

The organizational structure of WTO as summarized in Fig. 5.1, consists of the Ministerial Conference, General Council, council for each broad area, and subsidiary bodies.

First level – The Ministerial Conference:

The Ministerial Conference is the topmost decision-making body of the WTO, which has to meet at least once every two years.

Second level – General Council:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Day-to-day work in between the Ministerial Conferences is handled by the following three bodies:

i. The General Council

ii. The Dispute Settlement Body

iii. The Trade Policy Review Body

In fact, all these three bodies consist of all WTO members and report to the Ministerial Conference, although they meet under different terms of reference.

Third level – Councils for each broad area of trade:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There are three more councils, each handling a different broad area of trade, reporting to the General Council.

i. The Council for Trade in Goods (Goods Council)

ii. The Council for Trade in Services (Services Council)

iii. The Council for Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Council)

Each of these councils consists of all WTO members and is responsible for the working of the WTO agreements dealing with their respective areas of trade. These three also have subsidiary bodies. Six other bodies, called committees, also report to the General Council, since their scope is smaller.

They cover issues, such as trade and development, the environment, regional trading arrangements, and administrative issues. The Singapore Ministerial Conference in December 1996 decided to create new working groups to look at investment and competition policy, transparency in government procurement, and trade facilitation.

Fourth level – Subsidiary bodies:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Each of the higher councils has subsidiary bodies that consist of all member countries.

Goods Council:

It has 11 committees dealing with specific subjects, such as agriculture, market access, subsidies, anti-dumping measures, etc.

Services Council:

The subsidiary bodies of the Services Council deal with financial services, domestic services, GATS rules, and specific commitments.

Dispute settlement body:

It has two subsidiaries, i.e., the dispute settlement ‘panels’ of experts appointed to adjudicate on unresolved disputes, and the Appellate Body that deals with appeals at the General Council level. Formally all of these councils and committees consist of the full membership of the WTO. But that does not mean they are the same, or that the distinctions are purely bureaucratic.

In practice, the people participating in the various councils and committees are different because different levels of seniority and different areas of expertise are needed. Heads of missions in Geneva (usually ambassadors) normally represent their countries at the General Council level.

Some of the committees can be highly specialized and sometimes governments send expert officials from their countries to participate in these meetings. Even at the level of the Goods, Services, and TRIPS councils, many delegations assign different officials to cover different meetings.

All WTO members may participate in all councils, etc., except the Appellate Body, dispute settlement panels, textile monitoring body, and plurilateral committees.

The WTO has a permanent Secretariat based in Geneva, with a staff of around 560 and is headed by the Director-General. It does not have branch offices outside Geneva. Since decisions are taken by the members themselves, the Secretariat does not have the decision-making role those other international bureaucracies are given.

The Secretariat’s main duties are to extend technical support for the various councils and committees and the Ministerial Conferences, to provide technical assistance for developing countries, to analyse world trade, and to explain WTO affairs to the public and media.

The Secretariat also provides some forms of legal assistance in the dispute settlement process and advises governments wishing to become members of the WTO.

Essay # 6. Principles of the Multilateral Trading System under the WTO:

For an international business manager, it is difficult to go through the whole of the WTO agreements which are lengthy and complex being legal texts covering a wide range of activities.

The agreements deal with a wide range of subjects related to international trade, such as agriculture, textiles and clothing, banking, telecommunications, government purchases, industrial standards and product safety, food sanitation regulations, and intellectual property.

However, a manager dealing in international markets needs to have an understanding of the basic principles of WTO which form the foundation of the multilateral trading system.

These principles are discussed below:

(i) Trade Without Discrimination:

Under the WTO principles, a country cannot discriminate between its trading partners and products and services of its own and foreign origin.

Most-favoured nation treatment:

Under WTO agreements, countries cannot normally discriminate between their trading partners. In case a country grants someone a special favour (such as a lower rate of customs for one of their products), then it has to do the same for all other WTO members. The principle is known as Most-favoured nation (MFN) treatment.

This clause is so important that it is the first article of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which governs trade in goods. MFN is also a priority in the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS, Article 2) and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS, Article 4), although in each agreement, the principle is handled slightly differently.

Together, these three agreements cover all three main areas of trade handled by the WTO.

Some exceptions to the MFN principle are allowed as under:

i. Countries can set up a free trade agreement that applies only to goods traded within the group—discriminating against goods from outside.

ii. Countries can provide developing countries special access to their markets.

iii. A country can raise barriers against products that are considered to be traded unfairly from specific countries.

iv. In services, countries are allowed, in limited circumstances, to discriminate.

But the agreements only permit these exceptions under strict conditions. In general, MFN means that every time a country lowers a trade barrier or opens up a market, it has to do so for the same goods or services from all its trading partners—whether rich or poor, weak or strong.

National treatment:

The WTO agreements stipulate that imported and locally- produced goods should be treated equally—at least after the foreign goods have entered the market. The same should apply to foreign and domestic services, and to foreign and local trademarks, copyrights and patents.

This principle of ‘national treatment’ (giving others the same treatment as one’s own nationals) is also found in all the three main WTO agreements, i.e., Article 3 of GATT, Article 17 of GATS, and Article 3 of TRIPS.

However, the principle is handled slightly differently in each of these agreements. National treatment only applies once a product, service, or an item of intellectual property has entered the market. Therefore, charging customs duty on an import is not a violation of national treatment even if locally-produced products are not charged an equivalent tax.

(ii) Gradual Move Towards freer Markets Through Negotiations:

Lowering trade barriers is one of the most obvious means of encouraging international trade. Such barrier includes customs duties (or tariffs) and measures, such as import bans or quotas that restrict quantities selectively. Since GATT’s creation in 1947-48, there have been eight rounds of trade negotiations. At first these focused on lowering tariffs (customs duties) on imported goods.

As a result of the negotiations, by the mid- 1990s industrial countries’ tariff rates on industrial goods had fallen steadily to less than 4 per cent. But by the 1980s, the negotiations had expanded to cover non-tariff barriers on goods, and to new areas, such as services and intellectual property.

The WTO agreements allow countries to introduce changes gradually through ‘progressive liberalization’. Developing countries are usually given longer period to fulfill their obligations.

(iii) Increased Predictability of International Business Environment:

Sometimes, promising not to raise a trade barrier can be as important as lowering one, because the promise gives businesses a clearer view of their future market opportunities. With stability and predictability, investment is encouraged, jobs are created, and consumers can fully enjoy the benefits of competition—choice and lower prices.

The multilateral trading system is an attempt by governments to make the business environment stable and predictable.

One of the achievements of the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade talks was to increase the amount of trade under binding commitments. In the WTO, when countries agree to open their markets for goods or services, they ‘bind’ their commitments. For goods, these bindings amount to ceiling on customs tariff rates.

A country can change its bindings, but only after negotiating with its trading partners, which could mean compensating them for loss of trade. In agriculture, 100 per cent of products now have bound tariffs. The result of this is a substantially higher degree of market security for traders and investors.

The trading system under the WTO attempts to improve predictability and stability in other ways as well. One way is to discourage the use of quotas and other measures used to set limits on quantities of imports as administering quotas can lead to more red-tape and accusations of unfair play.

Another is to make countries’ trade rules as clear and public (transparent) as possible. Many WTO agreements require governments to disclose their policies and practices publicly within the country or by notifying the WTO. The regular surveillance of national trade policies through the Trade Policy Review Mechanism provides a further means of encouraging transparency both domestically and at the multilateral level.

(iv) Promoting Fair Competition:

The WTO is sometimes described as a ‘free trade’ institution, but that is not entirely accurate. The system does allow tariffs and, in limited circumstances, other forms of protection. More accurately, it is a system of rules dedicated to open, fair, and undistorted competition.

The rules on non-discrimination—MFN and national treatment—are designed to secure fair conditions of trade. The WTO has also set rules on dumping and subsidies which adversely affect fair trade. The issues are complex, and the rules try to establish what is fair or unfair, and how governments can respond, in particular by charging additional import duties calculated to compensate for damage caused by unfair trade.

Many of the other WTO agreements aim to support fair competition, such as in agriculture, intellectual property, and services. The agreement on government procurement (a ‘plurilateral’ agreement because it is signed by only a few WTO members) extends competition rules to purchases by thousands of government entities in many countries.

Essay # 7. Deadlock in WTO Negotiations:

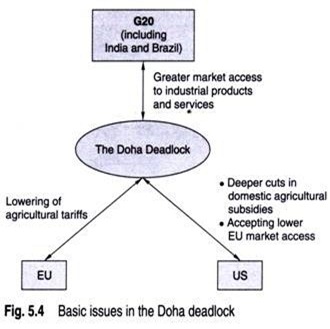

Despite intensive negotiations, deadlines were missed and negotiations across all areas of the Doha work programme were suspended mainly due to lack of convergence on major issues in agriculture and NAMA in July 2006. Agriculture remains the most contentious issue in the recent Ministerial Conferences, widening the developed- developing country divide.

Major developed countries continue to give high amount of subsidies to their farmers. Interestingly, developed countries have fulfilled their obligation of reduction in reducible subsidy in technical terms despite increasing the absolute amount of subsidy.

Besides, the EU and the US continue to give export subsidies as well. Ironically, developed countries are pressurizing developing countries to reduce their tariffs substantially. This poses a threat to the domestic farming sector of developing countries, which has got serious socio-economic and political implications.

This makes negotiations in agriculture extremely complex. Developed countries, on the other hand, are keen on market access for their industrial products.

The issues leading to the deadlock of the Doha negotiations are shown in Fig. 5.4. In order to reach a settlement, the complexity of issues between the key players had to be addressed and a compromise reached.

The US was looking for improved market access, with an average tariffs cut by around 66 per cent, while the G20 group of larger developed countries led by India and Brazil were looking for a cut of around 54 per cent.

The EU had offered a 46 per cent average tariff cut. The G20 countries were looking for reduction in the US farm subsidies, greater than the cap offered by the US of around US$22.5 billion, as well as improved market access through lower tariffs.

The EU was looking for improved market access to larger developing country markets for industrial products with a maximum tariff of about 15 per cent, besides improved access to services trade.

Any breakthrough in the negotiation process required further reduction of agricultural subsidies by the US, greater reduction in tariffs on agricultural goods by the European Union, and greater market access offered by larger developing countries such as India and Brazil to the industrial goods of other countries.

Essay # 8. Ministerial Conferences under World Trade Organization (WTO):

The highest decision-making body in the WTO is the Ministerial Conference (MC) that has to take place once in two years. Six ministerial conferences have taken place so far and have generated a lot of debate and controversies across the world, as discussed here:

(i) Singapore Ministerial Conference:

The first MC took place at Singapore during 9-13 December 1996 and reviewed the operations post-WTO. Major developed countries brought in proposals to start negotiations in some new areas, such as investment, competition policy, government procurement, trade facilitation, and labour standards. This evoked a lot of controversy.

Significant pressure was built up by the developed countries for all members to accept their proposals; this was strongly opposed by developing nations. However, an agreement was finally reached to set up working groups to study the process of the relationship between investment and trade, competition and trade, and transparency in government procurement.

These are generally termed as Singapore issues. The subject of trade facilitation was to be studied in the Council for Trade in Goods.

Conclusion of Information Technology Agreement was an important decision made during the Singapore Ministerial Conference based on the proposal brought by developed countries to have an agreement on zero duty on import of information technology goods.

(ii) Geneva Ministerial Conference:

The second MC, held at Geneva (Switzerland) during 18-20 May 1998, discussed implementation concerns of developing and least developing countries that led to establishment of a mechanism for evaluation of implementation of individual agreements.

The US-sponsored proposals for zero duty on electronic commerce were discussed and an agreement was reached to maintain status-quo on the market access conditions for electronic commerce for 18 months.

The agreement on status-quo actually meant that there would be zero duty on e-commerce since no country had been imposing duty on this mode of trade. A declaration on global electronic commerce was also adopted.

Electronic commerce was defined as the mode of commerce in which all operations of trade would be conducted through the electronic medium; these operations include placing the order, supplying the product, and making the payment.

They also include sale and transfer of goods through electronic medium, such as music and cinematographic products, architectural and machine drawings and designs, etc. However, the sale in which goods are physically transferred to the buyer would not be considered e-commerce.

(iii) Seattle Ministerial Conference:

The third MC, held in Seattle (US) from 30 November to 3 December 1999, witnessed dramatic changes in negotiations as the developing countries made intense preparations for the conference unlike in the previous MCs wherein issues brought in by the developed countries were chiefly discussed.

In Seattle too developed countries tried to push forward new issues, such as investment, competition policy, government procurement, trade facilitation, and labour standards. However, developing countries insisted upon priority attention to their proposals as these were related to the working of the current agreement, before any new issue could be considered.

No agreement on the issues could be arrived at, leading to a total collapse of the MC with a lot of confusion and without any decision.

(iv) Doha Ministerial Conference:

The fourth MC held during 9-14 November 2001, at Doha in Qatar further built up the divide between the developed and the developing countries in the WTO. On the one hand, developed countries were keen on formally pushing forward a new round of multilateral trade negotiations, which would include the issues of investment, competition policy, transparency in government procurement, and trade facilitation.

On the other hand, there was stiff resistance from developing countries to initiating a new round as they felt that they were still in the process of comprehending the implications of the last round, i.e., the Uruguay Round, of multilateral trade negotiations.

Finally a comprehensive work programme was adopted at the end of Doha MC. Although formally it was not called a new round of negotiations, the work programme had all the attributes of a fresh round of multilateral trade negotiations.

Members decided to work out modalities for negotiations on the Singapore issues and then start negotiations on the basis of the modality to be agreed by explicit consensus. It was also agreed upon to make Special and Differential (S&D) treatment for developing countries more precise, effective, and operational.

The main commitments of the Doha Declaration were:

i. To continue the commitment for establishing a fair and market-oriented trading system through fundamental reform of support and protection of agricultural markets, specifically through

a. Substantial improvements in market access

b. Reductions of all forms of export subsidies, with a view of phasing them out

c. Substantial reductions in trade distorting domestic support

ii. To give developing countries Special and Differential Treatment in negotiations to enable them effectively to take into account their development needs

iii. To ensure negotiations on trade in services aimed at promoting the economic growth of all trading partners and the development of developing and least developed countries

iv. To reduce or eliminate tariffs and non-tariff barriers in non-agricultural markets, in particular on products of export interest to developing countries

v. Doha Development Agenda (DDA) is a ‘single undertaking’ that means nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.

(v) Cancun Ministerial Conference:

The fifth MC was held in Cancun (Mexico) during 10-14 September 2003 under heightened strain between the major developed and developing countries. Developing countries believed that heavy subsidies on production and exports of agriculture in developed countries had been grievously harming their agriculture which is means of livelihood of their major population unlike in developed countries.

There was hardly any significant action perceived on the part of the developed countries in the areas of implementation of issues and Special and Differential Treatment. On the other hand, developed countries insisted upon starting the negotiations on the Singapore issues.

Under this atmosphere of complete apprehension, anger, and mistrust, no agreement could be reached and the MC terminated without any comprehensive declaration.

(vi) The Hong Kong Ministerial Conference:

The sixth MC took place in Hong Kong during 13-18 December 2005. It called for conclusions in 2006 of negotiations launched at Doha in 2001 and establishment of targets and time frames in specific areas.

The key outcomes of the Hong Kong Ministerial Conference included:

i. Amendment to TRIPS agreement reaffirmed to address public health concerns of developing countries.

ii. Duty free, quota free market access for all LDC products by all developed countries.

iii. Resolved complete Doha work programme and finalized negotiations in 2006.

iv. Elimination of export subsidies in cotton by developed countries in 2006; reduction of trade distorting domestic subsidies more ambitiously and over a shorter period.

v. Elimination of export subsidies in agriculture by 2013 with substantial part in the first half of the implementation period. Developing countries, such as India will continue to have right to provide marketing and transport subsidies on agricultural exports for five years after the end date for elimination of all forms of export subsidies.

vi. The agreement that the three heaviest subsidizers, i.e., the European Union, the US, and Japan, were to attract the highest cut in their trade distortion domestic support.

Developing countries like India with no Aggregate Measurement of Support (AMS) will be exempt from any cut on de minimus (entitlement to provide subsidies annually on product-specific as well as non-product specific basis each up to 10 per cent of the agricultural production value) as well as on overall levels of domestic trade distortion support (consists of the AMS, the Blue Box, and de minimus).

vii. Establishment of modalities in agriculture and Non-Agriculture Market Access (NAMA).

viii. The agreement that developing countries were to have flexibility to self-designate appropriate number of tariff lines as special products. In order to address situations of surge in imports and fall in international prices, both import quantity and price triggers have been agreed under the Special Safeguard Mechanism for developing countries.

ix. The agreement that in NAMA and Special and Differential Treatment (S&DT), elements such as flexibility and less-than-fall reciprocity in reduction commitments for developing countries reassured.

x. No sub-categorization of developing countries when addressing concerns of small, vulnerable economies.

Subsequently, at the General Council meeting held at Geneva on 31 July 2006, an agreement was reached on the framework in order to conduct the negotiations. Preliminary agreements were reached on broad approaches, especially in the areas of agriculture and industrial tariffs.

It was decided to drop the three Singapore issues on investment, competition policy, and government procurement whereas negotiations on trade facilitation were to follow.

Essay # 9. GATT/WTO System and Developing Countries:

Over the years, the divide between the developed and developing countries in the WTO has widened, leading to deadlocks in the process of multilateral negotiations. It has also triggered widespread demonstrations (Fig. 5.5) across the world due to conflicting interests of member countries.

Although developing countries form a much bigger group numerically under the WTO, decision making is significantly influenced by the developed countries.

The major issues of concern from the perspective of developing countries are summarized here:

i. The basic objective of the WTO framework is to liberalize trade in goods and services and protection of intellectual property. Countries with supply capacity directly benefit from expansion of exports whereas countries with intellectual property benefit from monopoly privileges, including high financial returns to owners of IPRs.

As most developing countries neither have good supply base for goods and services nor much of IPRs, their direct gains from the WTO system is much lower compared to developed countries.

ii. Reciprocity is the basis for liberalization under the WTO system. Countries get more if they are able to give more; conversely, they also get less if they give less. Since member countries have vastly diverse levels of development, there is an in-built bias in the system for increasing disparity among countries.

Although provisions such as differential and more favourable treatment have been incorporated in the WTO framework, these have several limitations and have hardly worked satisfactorily.

iii. Retaliation is the ultimate weapon for enforcement of rights of member countries. Since developing countries are weak partners and retaliation by them against any major developed country has both economic and political costs, they are at a considerably disadvantageous position in their capacity to enforce rights and obligations.

iv. The basic principles of the multilateral framework, such as national treatment, i.e., non-discrimination between imported and domestic goods, works against the process of development by discouraging domestic production by developing countries.

v. Developed countries significantly influence the decision-making process as they possess enormous resources to make elaborate preparations for the negotiating process. As their views are put forth effectively and strongly, the issues of their interest take centre stage leading to frustration among developing countries.

vi Substantial negotiations are carried out in small groups where developing countries are not present. Countries who have not participated are expected to agree when the results are brought forth in larger groups. It is difficult to stop decision-making at this stage as any such move by developing countries would mark them as obstructionists and have political repercussions.

vii. Developed countries often take advantage of escape routes and loopholes in the agreements. For instance, the Agreement on Textiles was back-loaded and left the choice of products to the importing countries.

As developed countries were importers and had been imposing restraints, they chose only such products for liberalization that were not under import restraints without significantly liberalizing their textile imports until the end of 2004 when the agreement was automatically abolished.

Similarly developed countries could fulfill their obligation of reduction of subsidies in agriculture despite actually increasing considerably the absolute quantum of subsidy.

viii. Developing countries view the WTO as an institutional framework to extract concessions from them, obstructing their goals of development and self-reliance. Despite vast differences among the interests of member countries, the WTO remains the only international organization that provides a multilateral framework for international trade.

Besides trade in goods, it covers a number of issues related to international trade, such as services, intellectual property rights, anti-dumping, safeguards, non-tariff barriers, dispute settlement, etc., making its approach highly comprehensive.