In this essay we will discuss about:- 1. Meaning of Monopolistic Competition 2. Features of Monopolistic Competition 3. Price Output Determination 4. Selling Costs.

Essay on Monopolistic Competition

Essay # 1. Meaning of Monopolistic Competition:

Economists found that perfect competition and pure monopoly were unrealistic market situations. The actual market situations are somewhere between perfect competition and pure monopoly. The theory of Monopolistic Competition was first propounded and popularised by an American economist E. H. Chamberlin. Sometimes monopolist competition is termed as Imperfect Competition also.

Now let us understand the meaning of monopolistic competition. As Stonier and Hague put, “It means the large group or firms making very similar products. Here there is keen but not perfect competition between many firms making very similar products (products are not homogeneous as in perfect competition or remote substitutes as in monopoly, but they are differentiated)”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the words of Dominick Salvatore, “Monopolistic competition refers to the market organisation in which there are many firms selling closely related but identical commodities.”

Thus monopolistic competition refers to the market situation in which many firms producing differentiated products (closely related but no identical products) compete with each other for the sale of their products.

So, monopolistic competition is a market situation with some elements of pure competition and some elements of pure monopoly. This explains the essential nature of monopolistic competition. It is competition between a large numbers of firms, each of them enjoying a measure of monopoly power. That is why; monopolistic competition is sometimes described as “Polypoly.”

Essay # 2. Features of Monopolistic Competition:

(i) Many Sellers:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There are large numbers of firms producing commodity in the market. Large number here implies that there are so many firms that the activities of one firm have no perceptible effect on the other firms in the industry. Each firm controls a very small or negligible share of the total output of the industry. The competitive element results from the fact that there are many firms in the market.

(ii) Freedom of Entry or Exit:

Every firm is free to enter into the industry and come out from the industry as and when it wishes.

(iii) Product Differentiation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Product differentiation is the most important feature of a monopolistic competition market. Under monopolistic competition products of different firm are neither completely homogeneous as in perfect competition nor entirely distinct as in monopoly.

Here each firm produces a products that is somewhat different from the products of its competitors, but it is not entirely distinct, it is very close to the products of other firms. Products of two or more firms are not exact substitutes but also are not entirely different. They are each other’s close substitutes.

But each firm is known for its own product, which has some distinction. For its product, the firm is a monopolist. But because of close substitutes, it faces competition with other firms. In fact, absence of differentiation would mean pure competition and perfect differentiation would mean pure monopoly. Partial differentiation, therefore, defines the nature of monopolistic competition.

There might, for example, be a large number of competing firms producing different brands of soap, all similar but by no means identical products. Each soap would differ in physical composition from competing soaps; it would also have different packing, and as the advertisers-say, a different ‘brand image,’ from its competitors.

Thus, products may be differentiated in many ways, e.g. by changing in brand name, trademark, design, packing, colour, size, weight, measurement, etc. We are giving some examples of product differentiation below so that the term could be understood more clearly.

—Cycle-Atlas, Estern Star, Hind, Hero, A-One etc.

—Sewing Machines-Usha, Luxmi, Singer, etc.

—Cigarettes-Wills, Gold Flake, Bristol, Taj, etc.

—Soap-Lux, Rexona, Hamam, Jai, Lifebouy, Pears, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

—Tea-Brooke Bond, Lipton, Modies, Tata, etc.

We can find a number of examples of such differentiated products. Cross elasticity of demand between such commodities is very high.

(iv) Each Firm is a Monopolist for its Product:

Every firm has a monopoly over the production of its product i.e., no other firm can manufacture the product of this brand name. For instance no firm other that the Atlas Cycle Company can manufacture Atlas Cycle or no firm other than Hindustan Lever can manufacture Lux toilet soap.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(v) Consumer Exhibits Market Preference:

In this market situation a consumer exhibits market preference for a particular product in the market. For instance, some consumers prefer Brooke Bond tea while others prefer Lipton.

Those who prefer a particular product would like to purchase it at even somewhat higher price.

(vi) Selling Costs:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Selling costs have an important place in this market. Every firm seeks to modify consumers’ preferences through advertisements and salesmanship. This gives rise to what is called selling costs. Thus there is non-price competition among firms under monopolistic competition.

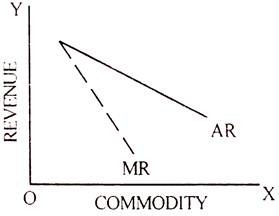

(vii) Independent Price Policy and Downward Sloping of AR-MR Curves:

A firm under monopolistic competition can have an independent price policy. It is price maker for its product. Hence the AR and MR curves facing a firm under monopolistic competition will be downward sloping similar to the monopoly.

But there is an important difference between the AR curves under monopoly and monopolistic competition. The AR curve under monopolistic competition is somewhat flatter than in the monopoly.

AR and MR curves of a firm under monopolistic competition are illustrated in the diagram:

Essay # 3. Price Output Determination under Monopolistic Competition:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Short Run Equilibrium in Monopolistic Competition:

In its characteristics monopolistic competition is closer to perfect competition, its pricing and output decisions are similar to those under monopoly because a firm under monopolistic competition, like a monopolist, faces a downward sloping demand curve. This kind of demand curve is the result of a strong preference of a section of consumers for the product, and the quasi-monopoly of the seller over the supply.

The strong preference or brand loyalty of the consumers gives the seller an opportunity to raise the price and yet retain some customers. And, since each product is a substitute for the other, the firms can attract the consumers of other products by lowering their prices.

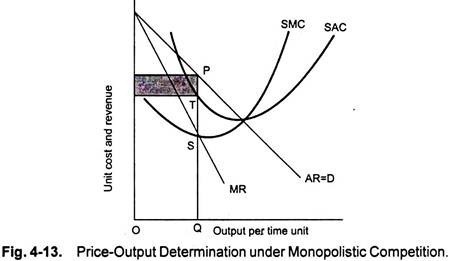

Figure 4.13 depicts the short term pricing and output determination under monopolistic competition.

SMC and SAC are the short run marginal cost curve and average cover curves of a monopolistic firm. Firm’s marginal cost curve cuts the marginal revenue curve at point S that satisfies the necessary condition of profit-maximization. Given the demand curve output OQ can be sold at price PQ. At this output and price, the firm earns a maximum economic profit PT per unit of output. The total profit earned by the firm is shown by rectangle P’PTP”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The typical firm can earn supernormal profit in the short run because of no possibility of new firm entering the industry. But the rate of profit would not be the same for all the firms under monopolistic competition because of difference in the elasticity of demand for their product. Some firms may earn only a normal profit if their costs are higher than those of others. For the same reason, some firms may make even losses in the short run to the extent of their average fixed cost.

Long- Run Equilibrium in Monopolistic Competition:

Figure 4.14 illustrates the price and output determination in the long run under monopolistic competition. Suppose that at some given time in the long run AR1 and MR1 are the average and marginal revenue curves and LAC and LMC are the long run average and marginal cost curves.

The figure shows that the long run marginal cost curve intersects marginal revenue curve at point R. This point determines the equilibrium output OQ1 and price P1Q1. At this price the firm makes a supernormal profit of P1S per unit of output. This situation is similar to short run equilibrium.

In the long run supernormal profit attracts new firms to the industry. Consequently, the firms within the industry lose a part of their market share to a new firm that shifts their demand curve downward to the left until AR is tangent to LAC. The increasing number of firms increases the price competition between the firms. Price competition also intensifies as losing firms try to regain their market share by cutting down the price of their product and new firms, in order to penetrate the market set comparatively low prices for their product.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The demand curve shifts downward, since the market is shared by large number of sellers. As the cost curves will not shift as entry occurs, each shift to the left of the demand curve will be followed by a price adjustment as the firm reaches a new equilibrium position, making the new marginal revenue on the shifted MR curve equal to its marginal cost. The process will continue until the demand curve becomes tangent to the average-cost curve and the excess profits are wiped out.

In the final equilibrium of the firm the price will be P2 and the ultimate demand curve AR2. This is an equilibrium position since price is equal to the average cost. Since profits are just normal, there will be no further attraction for the new firm to enter into the industry. The equilibrium is stable, because any firm will lose by either raising or lowering the price P2.

Essay # 4. Selling Costs in Monopolistic Competition:

Selling costs were introduced into microeconomic analysis for the first time by Chamberlin. He defines selling costs as “those [costs] which alter the demand curve” of the product. Thus, selling costs include sales promotion expenses, packaging and other marketing expenses, and advertisement expenditure.

Selling costs alter product demand. They also add to the seller’s costs. The total costs of the firm now include production as well as selling costs.

The equilibrium conditions in the presence of selling costs may be restated thus. At the profit maximizing output, the marginal total costs of the firm will be equated to its marginal revenue. This will also be the point of intersection of the dd and the DD curves, given the uniformity assumption. And given the uniformity assumption, the long run equilibrium conditions of the basic model may also be restated in terms of total costs. Thus, in the long run, the profit maximizing output of the firm will also provide the point of tangency of the dd and the LAC curve of the firm.

Inspite of formal similarity, there is an important difference between the equilibrium conditions in the basic model, and the one with selling costs. The costs of the firm in the latter model include selling costs. As a result, the meaning of the ‘excess capacity’ theorem is thrown into doubt. This is because, the decline in LAC in the long run equilibrium can no longer be automatically attributed to falling production costs. It could be that the average production costs are constant or rising, but the average selling costs are falling so strongly as to pull down the average total costs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Average Selling Cost Curve:

Do average selling costs rise or fall with output? It is difficult to answer this question on a priori grounds. Chamberlin himself seemed to believe that the average selling cost curve was U shaped. That is, selling costs were initially rewarded with increasing returns, followed by constant, and then diminishing returns. Initially increasing returns to advertisement expenditure is explained by economics of large scale, division of labour, greater availability of specialists at a larger expenditure, on the one hand, and by the effect of repetition in persuading consumers to buy the product on the other.

Diminishing returns are explained by the greater difficulty in persuading the less accessible consumers to buy, after the more accessible consumers are influenced. Many contemporary economists do not believe in an initial phase of increasing returns. However, there is general agreement on diminishing returns to advertisement expenditure.

Wastes of Competition and Advertisement Expenditure:

Excess capacity is one of the wastes of monopolistic competition. It is the price society pays for product heterogeneity. But product heterogeneity satisfies society’s desire for variety. This gain of society must be set off against the loss due to excess capacity. Advertisement expenditure is considered to be another waste of monopolistic competition. Critics of advertisement consider advertisement to be a socially unnecessary expenditure.

Thus Galbraith says:

“…it is not necessary to advertise food to hungry people, fuel to cold people, or houses to the homeless.” Galbraith seems to suggest that advertisement is not needed when wants are recognized. Sometimes advertisement is used to create wants. As a creator of wants, Galbraith sees advertisement as socially unnecessary. The role of advertisement as a creator of wants cannot be denied. But even when wants are recognised and concrete, advertisement provides socially useful information. Even the hungry, the cold and the homeless must know what is available, where, and at what price. Information can be obtained only at the cost of time or money, and sometimes both. Informational advertisement saves on these ‘search’ costs of the consumer, and presents to the consumer the alternatives available to him. Far from being a waste, it is a source of benefit to the consumer.”