For managing the exchange rate the government has to buy or sell foreign exchange as and when needed. This is known as intervention. For example, the US government on a particular day might buy $1 billion worth of US dollar with British pounds.

This would cause a rise in value, or an appreciation of the dollar. Here the US government is intervening in the foreign exchange market to artificially fix up the value of the dollar in terms of pound. As a general rule, the government will intervene when it believes that its country’s foreign exchange rate is higher or lower than is desirable.

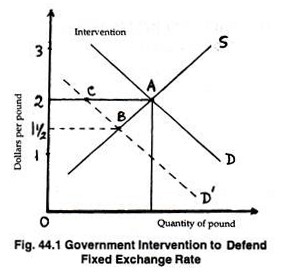

Fig. 44.1 illustrates the operation of a fixed exchange rate system. Now suppose America and Britain agree to maintain a fixed exchange rate of $2 per £1. The initial equilibrium is shown as a point A. At an exchange rate of $2 per £1, the quantities demanded and supplied of pound are equal.

Now suppose the demand for pounds falls due to brief recession in Britain or because the British interest rates fall. This leads to a shift in demand, from D to D’. Under a purely floating exchange rate system, the exchange rate would fall to a new equilibrium at B, producing a depreciation of the pound (or equivalently, an appreciation of the dollar).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now the question:

Can Britain and America maintain parity of $2 per pound. What are the policy options of the two countries?

1. The easiest approach is to intervene by buying the depreciated currency (pounds) and selling the appreciating currency (dollars). In Fig. 44.1 if the two central banks, viz. Bank of England and the Federal Reserve Bank of U.S.A. buy CA amount of pounds from the foreign exchange market, this amount will disappear immediately. This means that the demand for pounds will increase and the official parity can be maintained.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. A preferable alternative would be to use an appropriate monetary policy. The two central banks could induce the private sector to increase the demand for pounds by raising British interest rates.

If the US interest rates fall relative to British rates, this would lead investors to move funds from America to Britain and increase the private demand for pounds, in effect moving the private demand curve back toward the original D.

These two approaches are not really different. In effect, both involve increase in the money supply in different markets. In fact, one of the complications of managing the open money, as Paul Samuelson and his co-authors have pointed out, “is that the need to use monetary policies to manage the exchange rate can collide with the need to use monetary policy to stabilize the domestic business cycle.”