The following points highlight the top three effects of Fiscal Policy on the Balance of Trade. The Effects are: 1. Domestic Fiscal Policy 2. Expansionary Fiscal Policy in the Rest of the World (ROW) 3. Effect of an Investment Tax Credit

Effect # 1. Domestic Fiscal Policy:

Suppose the government of the home country spends more. If G increases, S will now be less than the fixed level of investment at an unchanged r*.

Now the excess of domestic investment over domestic saving has to be covered by borrowing funds from abroad.

A fall in S automatically leads to a fall in NX = (S-1). This means that an increase in G creates a trade deficit in a small open economy, which initially started from a position of trade balance (i.e., neither a deficit nor a surplus).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A cut in taxes has the same adverse effect on trade balance. If the government reduces taxes (T), disposable income (Y – T) rises, consumption increases and national saving falls. Since NX = S – I, a fall in S reduces NX.

Fig. 6.2 shows how fiscal policy reduces national saving. A change in fiscal policy that in creases C or G reduces (Y – C – G). This shifts the vertical saving line leftward from S0 to S1. Now, NX, which is excess of S over I, falls. So, an expansionary fiscal policy creates a trade deficit.

Effect # 2. Expansionary Fiscal Policy in the Rest of the World (ROW):

Now suppose the foreign governments increase their expenditures. This reduces saving of the ROW. As a result, the world rate of interest rises.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The increase in r reduces the volume of investment in the small open economy by raising the cost of borrowing. Since there is no change in S, S now exceeds I. Since financial capital has an extra temptation to go abroad, a portion of this excess domestic saving will now flow to ROW in search of higher return. Thus, a fall in I will also increase the balance of trade (or, NX = S – I).

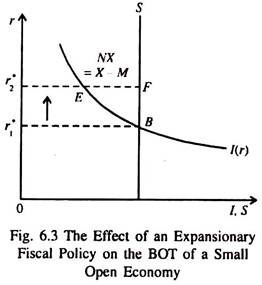

Fig. 6.3 shows the effects of the adoption of an expansionary fiscal policy on a small open economy. In this case, domestic saving and investment curves remain unchanged. However, a rise in the world interest rate from r1* to r2* converts a situation of balanced trade to a surplus (measured by the distance EF).

The difference between the two situations is that in Fig. 6.2, the trade deficit (M – X = S – I) results at the original real rate of interest (r1*). But in Fig. 6.3, trade surplus results because of a rise in the world rate of interest from r1* to r2*. Since fiscal expansion abroad leads to a rise in r, it generates an excess of domestic saving over domestic investment and this is the trade surplus: X- M = S- I.

Effect # 3. Effect of an Investment Tax Credit:

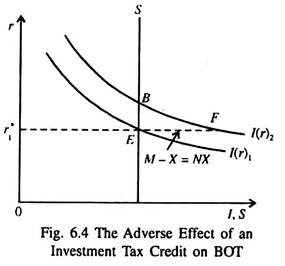

An attractive fiscal concession offered by modern governments to business firms is investment tax credit or an investment subsidy. This type of positive fiscal policy has a favourable effect on investment. Fig. 6.4 shows that if such a fiscal concession is offered, the investment demand curve shifts to the right. This means that investment demand increases at every rate of interest.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, at the prevailing world interest rate (r1*) the volume of investment is now higher. So, there is an excess of I over S (since S remains unchanged). This has to be financed by foreign borrowing. This means that the net outflow of capital negative (or net capital inflow is positive). Alternatively interpreted, since: NX = S – I, an increase in I implies a fall in NX.