In this article we will discuss about fixed or pegged and flexible or fluctuating exchange rate system.

Fixed or Pegged Exchange Rate System:

In the case of fixed or pegged exchange system, all the international transactions take place at the rate of exchange fixed by the monetary authority. The exchange rate is either fixed by the government through legislation or it comes into existence through the intervention in the foreign exchange market by the authorities.

If the rate of exchange diverges from the fixed equilibrium level due to market forces or the activities of speculators, the monetary authority or government interferes in the foreign exchange market and maintains the rate of exchange at the equilibrium level.

The market intervention in such a situation is called as pegging, i.e., the sale or purchase of foreign exchange in the foreign exchange market. It is just like the buffer stocks operation in foreign exchange. The authorities buy the foreign exchange when there is excess supply of it and sell it out when there is excessive demand for it in the exchange market. The pegging operations facilitate the maintenance or ‘pegging’ of the rate of exchange at the desired equilibrium level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

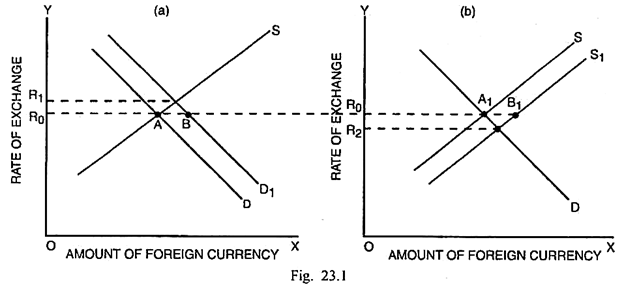

The fixed or pegged rate of exchange can be shown through Fig. 23.1 (a) and (b). In Figs. 23.1(a) and (b), the amount of foreign currency is measured along the horizontal scale and the rate of exchange is measured along the vertical scale. In Fig. 23.1 (a), the equilibrium fixed official rate of exchange is R0 determined by the intersection between the demand and supply function D and S respectively.

If the demand for foreign currency increases such that the demand function shifts from D to D1, given the exchange rate, there is excess demand gap which is likely to appreciate the exchange value of foreign currency in terms of domestic currency to R1 or cause corresponding depreciation in the exchange value of domestic currency.

In order to peg or maintain the exchange rate at R0, the excess demand gap AB is neutralized through the sale of foreign currency in the foreign exchange market.

It is possible for the government or monetary authority of the home country to fill up the foreign exchange gap AB in any of three possible ways:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) Reduction in the foreign exchange reserves built through BOP surplus in past years (which implies sale of foreign exchange),

(ii) Borrowing of short-term funds externally as accommodating transactions, and

(iii) Export of monetary gold.

The resort to any one of the measures will help maintain the exchange rate at the official level rate of exchange R0.

In Fig. 23.1 (b), the fixed official rate of exchange is again R0. If there is an increase in the supply of foreign currency due to BOP surplus, the supply curve shifts to the right from S to S1. This creates an excess supply gap A1B1. Consequently, the exchange value of foreign currency in terms of domestic currency depreciates to R2 or there is a corresponding appreciation in the exchange value of domestic currency.

In order to peg or maintain the exchange rate at the official level R0, the government or monetary authority will be obliged to buy the foreign currency in the exchange market. Thus in a system of fixed exchange rates, the pegging operations (sale or purchase of foreign currency) can help maintain the equilibrium rate of exchange at the official level.

Flexible or Fluctuating Exchange Rate System:

The flexible or fluctuating exchange rates are determined by the free working of the market forces. If there is an excess of demand for foreign currency over its supply, the foreign currency appreciates whereas the home currency depreciates. On the opposite, when the supply of foreign currency exceeds the demand for it, the foreign currency depreciates and the exchange value of home currency appreciates in terms of the foreign currency.

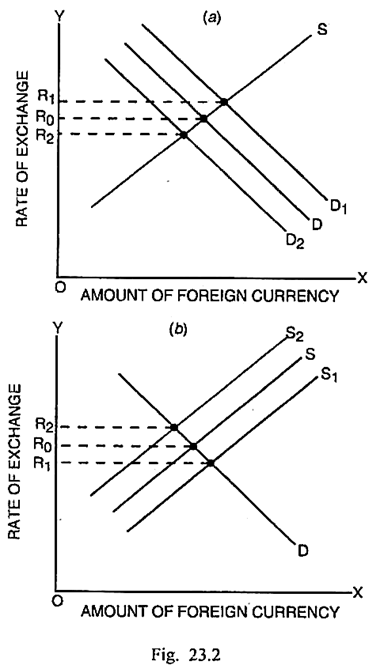

Thus there are appropriate variations in the exchange rates to maintain the BOP equilibrium. The impact of changes in demand for and supply of foreign currency upon the rate of exchange and consequent effect on the BOP adjustments can be shown through Figs. 23.2 (a) and 23.2 (b).

In Figs. 23.2 (a) and (b), the amount of foreign currency is measured along the horizontal scale and rate of exchange is measured along the vertical scale. In Fig. 23.2 (a), given the demand and supply functions of foreign currency D and S, the initial equilibrium rate of exchange is R0. If demand increases and demand function shifts to the right to D1, there is excess demand for foreign currency at R0 rate of exchange. The excess demand pressure causes an appreciation of foreign currency to R1 (depreciation of home currency).

This movement of exchange rate restores the balance of payments in an automatic manner. On the opposite, if a decrease in the demand for foreign currency causes a shift in the demand function to D2, there is deficiency of demand for foreign currency at R0 rate. As a result, the foreign currency depreciates to R2 (appreciation of home currency). This movement of rate of exchange neutralizes any possibility of BOP surplus and keeps the system in a state of balance.

In Fig. 23.2 (b), the original equilibrium rate of exchange is R0. If there is an increase in supply of foreign currency, the supply function shifts to the right to S1 causing depreciation in foreign currency R1 (appreciation of home currency). On the opposite, a decrease in supply causes a shift in the supply function to the left to S2. There is shortage of the foreign currency at the original rate. It leads to an appreciation of foreign exchange upto R2 (depreciation of home currency).

Whether there is a BOP deficit or surplus, it can be easily and rapidly offset by the free movement of the exchange rates. The monetary or fiscal authorities are not required to intervene to correct the BOP disequilibrium. The market forces of demand and supply operate in an automatic way and no need is felt for making accommodating capital transactions for achieving or maintaining the BOP equilibrium. The flexible exchange rates are also called as floating exchange rates.

Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rates:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The case for and against the fixed and flexible exchange rates was examined separately. The crucial question in this connection is which of the two systems can be considered as better. There is no clear cut answer to this question. In this connection, Sodersten opined, “The answer will depend on circumstances. It will depend on the characteristics of the economy, and it will change with time as the economy changes.”

The fixed or pegged exchange system is wasteful; creates shortage of liquidity; causes international transmission of fluctuations; and relies excessively upon controls and bureaucratic intervention. In addition, it cannot provide appropriate remedy to the problem of long-term BOP disequilibrium.

The flexible exchange rates, on the opposite, involve certain problems such as uncertainty, exchange risk, destabilising speculation and inflationary bias. In the fixed exchange system even though exchange rate may be fixed but one currency may either is over-valued or under-valued. In such circumstances, despite stability of exchange rates, serious impediments continue to exist in international trade and investments. As regards speculation, its impact may be felt even when the exchange rate is fixed.

Only difference is that speculation is not about the exchange rates, it is connected with pegging and other controls. The flexible exchange system is often blamed for generating inflationary pressures. But the countries passed through serious inflationary strains even during the periods when fixed exchange system remained dominant. Both under gold standard and IMF stable exchange parities, inflation did affect the economic activities in many a country.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The flexible exchange system has some highly significant merits such as continuous and automatic adjustment, absence of exchange and other controls, economical and beneficial for international trade. It helps alleviate the problem of international liquidity and reinforces the monetary and other economic policies.

A 1989 study showed that out of 151 IMF members, at that time, 96 countries operated under a fixed exchange system. These were primarily small developing countries. Many of them had pegged their currencies to the currencies of their main trade partners. In that way, they wanted to limit the fluctuations in the prices of their exports and imports. They had also expected to achieve in this way greater stability of output and employment. Some of them had pegged their currencies to a basket of currencies. In contrast, only 55 countries were having some measure of exchange flexibility.

But these included all the large industrial nations such as the U.S.A., Japan, Britain, France, Germany, Canada and Italy. Some large developing and semi-industrialised countries like India, China. Indonesia, Philippines, Mexico, Spain and Argentina too had some form of exchange rate stability.

It is relevant to point out here that about four-fifths of the world trade is presently between those countries which have some measure of exchange rate flexibility. The present system thus exhibits a large degree of flexibility and more or less allows each nation to choose the exchange rate regime that best suits its preferences and circumstances.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally to conclude in the words of Sodersten, – “Where a system of fixed or flexible exchange rates will prevail, will depend on economic circumstances. In times of reasonably calm economic development, the prospects for fixed exchange rates are good. If the world economy experiences great stress and large disturbances, fixed exchange rates will not be operational and flexible rates are likely to develop.”