Read this article to learn about the different views given by renowned economist on full employment!

Classical Views on Full Employment:

Fear of unemployment, described as “the shadow side of progress”, constantly haunts the working classes.

The classical economic theory rests on the assumption of full employment of labour and other resources within an economy.

According to classicals the normal situation in any economy is stable equilibrium at full employment. Full employment was defined as a situation when there is no “involuntary unemployment”, though there may be frictional, structural or voluntary unemployment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A worker is said to be voluntarily unemployed when he refuses to work at the current wage rate or one refuses to work at all. For example, a worker who goes on strike demanding higher wages was considered by Classicals to be voluntarily unemployed, for he can be employed if he is just prepared to accept the current wage rate. Similarly, voluntary unemployment exists when the potential workers are unwilling to accept less wages; they include persons who have enough to depend upon the income derived from the large property which they happen to possess.

Frictional unemployment exists because the workers do not possess the necessary skills or are located in the wrong places or unsuitable jobs. Frictional unemployment is caused on account of the immobility of labour, seasonal nature of work, temporary shortages of raw materials, breakdowns of machinery, ignorance about job opportunities, etc. Technological unemployment is the result of changes in the techniques of production. This type of unemployment is caused when machines replace men.

Seasonal unemployment arises in a particular industry through seasonal variations in its activity brought about by climatic conditions or by changes in fashions. This is the simplest and most obvious type. The effects of the weather and of customary buying patterns are implicit. Many consider to be a kind of frictional unemployment. The dimensions of seasonal unemployment, despite its apparent simplicity are by no means clear.

Structural unemployment is said to exist when large number of persons are unemployed or underemployed not because they want to remain idle or underworked, but because the co-operant factors of production to engage them fully are not sufficiently available. There may be scarcity of land, capital, or skill in the national economy causing structural disequilibrium (unemployment) in the labour sector. This type of unemployment, while commonly recognized, is one of the most difficult to define clearly and consistently.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Distinctions between frictional and structural unemployment are not sharp; sometimes one is considered to be a part of the other. Both are considered as results of difficulties of adjustments of labour demand and supply in a dynamic economic system in which there are continuous changes in technology, tastes, plant location, uses and distribution of labour and other resources. The word structural implies economic changes that are massive, extensive and deep-seated. Cyclical type of unemployment gets its name from the changes occurring during the recession phase of the trade cycle.

Pigou defined unemployment as a residual, to be calculated by subtracting employed workers from the number of would-be-wage-earners. To Pigou, unemployment was caused on account of imbalances or maladjustments within the economic system and, therefore, employment became more a matter of balance or adjustment. According to Prof. Beveridge (one of the contemporaries of the classical economist, Prof. A.C. Pigou), full employment does not mean virtually no unemployment.

In a dynamic and developing economy, where some frictional unemployment is bound to be there, it should be taken to mean that state of the economy where unemployment is reduced to short intervals of standby, with the surety that very soon one will be wanted in one’s old job again or will be wanted in a new job that is within one’s power. To Beveridge, it means more vacant jobs than unemployed men so that normal lag between losing one job and finding another will be very short. Lord Beveridge estimated 3 per cent normal unemployment for Great Britain even in times of full employment.

He estimated that 1 per cent of the working population would be “between jobs” at any particular time, 1 per cent would be out of work because of seasonal variations in employment, and further 1 per cent would be unemployed because of fluctuations in export industries giving a total of 3 per cent as the measure of “frictional unemployment”, in a situation of full employment. Thus, there is a standard what has been called “tolerable unemployment” compatible with full employment as no economic system can be expected to behave perfectly for an indefinite period. There is, however, no general agreement as to the percentage of unemployment that is compatible with full employment. To most economists’ full employment is a goal to be aimed at though it may not be always realized.

Keynes’ Views on Full Employment:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynes discussed unemployment under three categories: frictional, voluntary and involuntary. According to Keynes frictional unemployment includes unemployment caused by various inexactness’s of adjustment which stand in the way of continuous full employment. Unemployment, which he called voluntary unemployment, resulted from the refusal of the worker on account of collective bargaining or any other such reason to accept a reward corresponding to his marginal productivity.

In his view, the third type of unemployment called involuntary unemployment resulted from the deficiency of effective demand (also called demand deficiency unemployment) because there are unemployed men who would be willing to work at less than the existing real wage. According to Keynes, at the full employment level of economic activity, there could be frictional or voluntary unemployment but no involuntary unemployment. The basic aim of Keynes’ theory was to discover that determines at any time the national income of a given economic system (which is almost the same thing) and the amount of its employment.

Keynes thus agreed with the Classicals that structural, frictional, and technological unemployment can coexist with full employment, but he did not agree with the Classicals that there is always full employment in the economy; what actually exists in the economy is less than full employment. Keynes defined full employment in terms of elasticity (increases and decreases) of output in response to an increase in effective demand. According to him, full employment is a situation beyond which an increase in effective demand does not result in an increase of output and employment.

Once full employment has been attained, no further increase in employment is possible as a result of an increase in effective demand which becomes inflationary in the sense that it spends itself in rising prices. Keynes’ formulation of full employment, thus, involves an appropriate amount of effective demand, a unique level of employment beyond which no further increases in employment are possible and any increase in effective demand will lead to a more rise in prices and practically no increase in employment. In other words “full employment may be considered as a situation in which employment cannot be increased by an increase in effective demand.”

Full Employment—Views of Leading Economists:

It is, therefore, not easy to say precisely what ‘full employment’ is. It certainly cannot mean that every machine and every factory, no matter how defective, must be operated twenty-four hours so that every mine no matter how poor its deposits must be developed to the point of exhaustion. Such questions clearly show that any attempt to define full employment in terms of the, use of capital facilities or natural resources is beset with lot of difficulties like finding a definition, criteria for its measurement, standard of tolerable unemployment, etc. Thus, it is rather difficult to give a precise and yet generally acceptable definition of full employment, though it is much talked of in Keynesian economics.

It is a concept which has often been misunderstood and requires explanation. Prof. Gardner Ackley calls it “slippery concept” for it does not mean zero unemployment. American Economic Association Committee defines full employment as follows: “Full employment means that qualified people who seek jobs at prevailing wage rates can find them in productive activities without considerable delay. It means full-time jobs for people who want to work full-time it does not mean that unemployment is ever zero.”

In a dynamic economy in which new industries are developing and old ones are declining, there is bound to be a high degree of labour mobility and transitional unemployment. Even with an excess demand for labour some workers are idle for seasonal reasons, some workers having lost a job have not yet moved to fill a vacancy, new entrants in the labour force need some time to settle down, some workers cannot hold a steady job on account of mental, physical, and emotional handicaps. Thus, full employment is a concept which is compatible with a certain amount of unemployment.

Orme Phelps meant by full employment not only optimum employment of labour but of all kinds of resources, including capital and raw materials. There is optimum production of goods and services. According to him, the full employment of the people implies a broader distribution of income that might occur in a more productive but less equalitarian society, placing the emphasis upon the allocation of income instead of its amount. The stress is on the security than on productivity. Paul A. Samuelson means by full employment that reasonably efficient workers, willing to work at the currently prevailing (fair) wage rate, need not find themselves unemployable as a result of too little general demand.

According to A.P. Lerner full employment is a situation when workers can find employment without depressing wages as well as a situation when further spending would inflate factor prices. Allan G.B. Fisher has taken the view that definition of full employment is primarily a political matter. He feels that in practice government will be content to define full employment as “avoiding that level of unemployment, whatever it may happen to be, there is good reason to fear, may provoke an inconvenient restlessness among the electorate” I.L.O. was of the opinion that when only 3 per cent to 4 per cent unemployment exists in a country, the country can be said to have reached full employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Other conditions of full employment mentioned by I.L.O. are that there should be no exploitation of labour and that the workers should be able to find alternate employment early. According to Cairn cross, there is seller’s market in full employment and threat of unemployment can no longer be used like a whip to make labour conform to the standards of his place of employment. The labour has so strong collective bargaining that if used to raise wages, it will bring inflation.

Full Employment—A Delusion:

There are still a few economists who think that full employment should be conceived as just a “means to an end” and not as “end” in itself. Like the classical economists, they were of the opinion that deliberate efforts to reach full employment will be harmful. Like classical economists, they argue that we should devote more attention to the problem of achieving maximum production rather than trying to attain full employment. They consider full employment ideal as an impracticable ideal in a dynamic society and consider that a close approach to it may be inflationary and injurious to efficiency.

They also regard the transfer of economic responsibility from the individual to state (which may be necessary to achieve the object of full employment) as running counter to deep rooted convictions. Such economists use the term full employment with hesitancy. They regard the goal of full production as more important. They regard that full employment focuses attention on jobs rather than output. They want certain amount of unemployment to ensure discipline among the workers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Henry Hazlitt, who is an avowed anti-Keynesian economist, says, “Full employment is not definable not should it be defined.” This is so because measurements of employment are based upon the unreliable sample studies. The full employment is relevant to working hours. If working hours are five hours a day while a man is considered to be capable of working say seven hours a day, there is hidden unemployment, which has simply been redistributed.

Therefore, Hazlitt says, “When we speak of full employment we should do better to use the term not as the Keynesian zealots use it, and not with any effort at any unattainable mathematical precision but in a loose, commonsense way to mean merely the absence of substantial or abnormal unemployment.” He goes on to say that full employment should not be made the end as such. He says, “Primitive tribes are naked, and wretchedly fed and housed, but they do not suffer from unemployment.

China and India are incomparably poorer than ourselves but the main trouble from which they suffer is primitive production methods and not unemployment.” He further goes on, “Nothing is easier to achieve than full employment. Once it is divorced from the goal of full production and taken as an end in itself.” Hitler provided full employment with a huge armament programme.

The War provided full employment for every nation involved. The slave labour of Russia had full employment. Prisons and chain gangs have full employment. Coercion can always provide full employment. We can very easily have full employment without full production. But we cannot continuously have the fullest production without full employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, despite the fact that some think that full employment is a delusion, it is now considered as the chief aim towards the achievement of which wage, income, monetary, and fiscal policies are directed. All presidents of the U.S.A, including President Jimmy Carter have paid serious attention to this problem. In all countries whether capitalist or socialist this has been the chief concern of governments.

The Aggregate Demand—Will It be Enough?

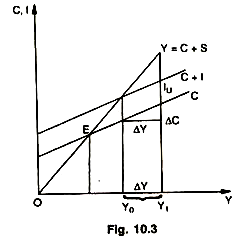

Costs will fall as a result of fall in money wages and, as suggested by the theory of the firm, it will lead to an increase in output and employment. But will the increase in output be consumed? In other words, will there be enough aggregate demand? Because the MPC is less than unity, only a fraction of the additional output will be consumed, so that the remainder output must be absorbed in the form to investment or intended investment, if the enhanced level of output and employment is to be maintained. If the investment or intended investment does not increase, the result will be an accumulation of stocks or unintended inventory; as a result the prices will fall, and output and employment may fall back to their original levels. Fig. 10.3 given further fully illustrates the point under consideration.

In the figure the aggregate demand schedule C + I cuts the 45 degree line at income Yo. The full employment income is at Yo– Since the level of income is less than full employment level, there must be an excess supply of labour. As a result, money wages will be falling. Suppose as a result of a fall in money wages firms produce Δ = Y1 – Y0 additional units of output.

If no new taxes are levied, increased output creates additional income by the same amount. But since the MPC is less than unity, the increase in consumption ΔC is less than ΔY and the difference represents stocks or unintended accumulation of inventories Iu. Now equilibrium cannot be established unless this unintended investment is eliminated, falling which prices will fall and output will return to original level Y0— real wages remain the same and the market clearing mechanism through fall in wages fails to operate.

Now, to a classical economist this is inconceivable or not possible. He would continue to argue that as long as there is un-cleared labour market and as long as thorough going competition will put downward pressure on wages and prices, the real value of money supply will increase; this will force down interest rates ; raise the level of investment and increase the level of income, output and employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since prices and wages must continue to fall as long as there is some involuntary unemployment, investment and income must continue to rise until unemployment is eliminated. In other words, if unemployment exists, it may be due to over-production or the failure of the economy to spend at a rate sufficient to justify production at the level associated with a given volume of employment and not due to any deficiency in total or aggregate demand or not because of any error in the classical analysis of the nature of demand for and supply of labour.’

The Theory of Price Level:

The final building block in the classical structure is theory of the price level, that is, how the general level of prices in the economy is determined? This theory also explains the role that money occupies in the classical scheme. They did not give much importance to money except treating it as a medium of exchange its role as a store of value was not considered. According to them money facilitated the transaction of goods but had no effect on income, output and employment.

They considered money as a veil. They completely ignored the precautionary and speculative motives for holding money. Their approach is contained in what is called ‘quantity theory of money’. Despite, differences amongst classicals on various versions of the quantity theory, they concentrate on the relationship between the quantity of money in circulation and the general level of prices. A good starting point is the equation of exchange.

MV = PT or PY

In this equation M is the supply; V the velocity; P the general price level and T the volume of goods and services or real income also denoted by Y. Expressed in this way, the equation of exchange is a simple truism or an identity because it follows that the quantity of money multiplied by its velocity (number of times each unit of money is used or spent) is equal to the goods and services produced (T or Y) times the average price level (P). Classicals assumed V and T to be constant as such M and P varied in the short period and established the casual relationship between money supply and price level.

This relationship was direct and proportional, i.e., if the quantity of money doubles, the price level also doubles. In other words, the classical quantity theory of money asserts that the general price level is a function of the supply of money—P = ƒ (M). This identity shows clearly that the entire amount of money made available by the monetary authority is to be spent for the purchase of commodities and services and there is no rational ground for holding money as passive balance or for any other purpose. If for some reason the supply of money at a particular time is different from or exceeds the demand for money, the necessary changes in the general level of prices will restore equilibrium between the demand for and supply of money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is the essence and the main feature of the classical quantity theory of money as long as the assumptions that quantity of money is held for transactions and that wages and prices are flexible in downward direction hold true. It makes the quantity theory of money and Say’s Law (i.e., the identity MV = PT) perfectly consistent with each other.

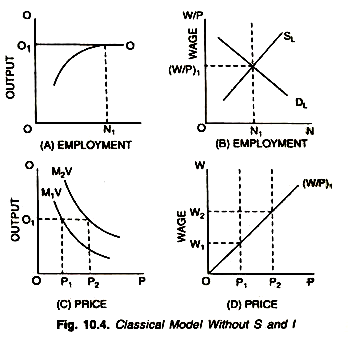

Classical Model Without Saving and Investment:

The level of employment in the classical system has been shown as being determined by the demand for and supply of labour; the level of output as being determined (with a given production function) by the level of employment; and the level of prices as being determined by the supply of money.

Fig. 10.4 illustrates the interrelationships amongst these variables of the classical model but without saving and investment:

In Fig. 10.4, part B shows the intersection of two curves and determines the point of full employment (N1), and the real wage (W/P)1 which is necessary to achieve this full employment. This real wage and employment at N1 determine full employment output (O1) in part A. The price level of output (O1) depends on M and V, and the curve M1V shows a particular quantum of money supply (with constant velocity of money). From the identity MV = PO (once M1V and O are known) we get the price level (P = MV/O).

In part C, given M1V and O, the price level is P1. Part D shows the money-wage adjustment necessary to establish equilibrium. At the given price level (P1) established in part C, the required money wage is accordingly established at W1 in part D. If the actual money-wage in the market is higher than W1 (the money- wage which establishes full employment in Fig. 10.4) then, the resulting unemployment and competition amongst workers for jobs will force the money wage to fall till the system regains its full employment equilibrium position at W1. This simple classical model as shown in Fig. 10.4 enables to identify the full set of equilibrium values of the classical system—namely, employment (N1), output (O1), price level (P1) and money wage (W1).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In case there is no shift in the production function or the supply curve of labour or in the money supply and its velocity—the indicated set of equilibrium values will remain unchanged period after period. But in actual practice, these elements or determinants will change over time and for each such change (under the classical system), new equilibrium values will be established for these variables of the system. Tracing through these changes will illustrate the mechanics of the system.

To understand the model properly alternate changes in variables M, D1, and production function can be examined with their corresponding effects on other variables.

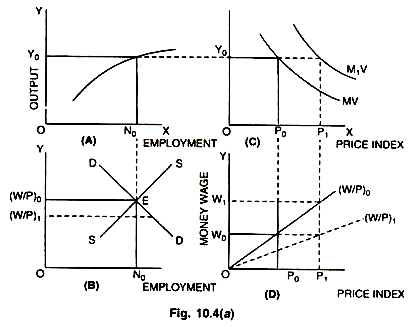

Effects of Change in the Quantity of Money:

The values of (W/P)0, W0, P0, Y0 and MV0 are given in conditions of equilibrium as shown in Fig. 10.4(a). Effects on these values of an increase in quantity of money would cause a proportionate rise in price level in the absence of nil increase in output. This will push up the money wages in proportion to price level such that the real wage remain unaffected, hence, employment and output are left unaffected.

Part C of the diagram shows that an increment in quantity of money raises the MV line to M1V. Since the output is constant, the price level would rise to P1, because, the larger quantity of money would use in exchange over the same quantity of output.

Part D shows if an increase in price to P1 is not accompanied by a rise in money wage, the real wage will fall to (W/P), as shown in part (B). But at this real wage demand for labour is higher than its supply. This will raise the money wage to W1 in part (D) in proportion to the price level such that real wage reaches its original level, i.e., (W/P)0.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Part (A) and (B) are the real sectors and Part (C) and (D) reflect monetary sectors. Change in real sector can bring about a change in monetary sector but not vice versa.

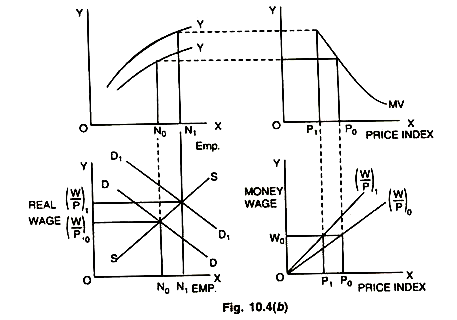

Effects of a Change in the Demand for Labour:

Consequent upon technological improvement or an increase in the capital stock the production function may shift upward as shown in Fig. 10.4(b) by Y1. Its steep slope as compared to production function Y causes the MPP curve to shift upward resulting in the upward shift of the demand curve for labourers shown by D1D1.

The other variables, shown by zero, were previously determined under conditions of equilibrium. But now after an upward shift in the demand curve employment increases to N1 income to Y1 and P falls to P1. Real wage rises to (W/P)1 from (W/P)0 given the money wage constant. Under the new set of equilibrium the other variables shown by symbol one has been determined.

Students can practise themselves such changes in N, Y, P, W and W/P by introducing a change in supply of labour.

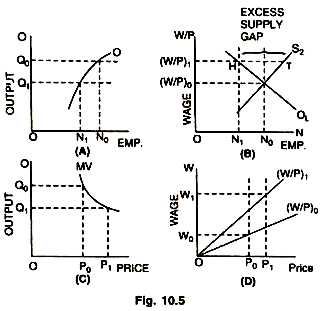

Effect of Rigid Money Wage:

We know that the classical theory of employment is based on the assumption that wages and prices are flexible in downward direction especially when there is excess supply of goods or labour. This will remove excess supply of goods or labour (unemployment). In Fig. 10.5 we examine what will happen if there is no perfect competition and no downward flexibility of wages and prices. Such a situation is possible now-a-days.

There are trade union pressures, collective bargaining and refusal of workers to allow any reduction in money wages. In other words, money wages may be rigid in downward direction but quite flexible in upward direction. Fig. 10.5 examines the effects of such a situation on Y, O and E.

In part B, the initial equilibrium is at N0 (full employment level), the real wage rate in (W/P)0 and the level of output O0. Now, if the money wages are high at W1 so that the real wage rate is (W/P)1; the level of employment is N1 and the excess supply of labour is shown by HT. At lower level of employment (N1) the output is O1. Given the money supply curve MV, a fall in output from O0 to O1 will mean increase in prices from P0 to P1 (it is necessary because a small output is bound o to be accompanied by an increase in prices, given the money supply).

The increase in prices is likely to be less than the Q proportionate increase in money wages— because if the prices increased in the same proportion as the money wages, the real wage rate would remain unchanged and the employers may continue to produce the same output as before—but this is again unlikely and quite inconsistent because employers cannot sell the same quantity at higher prices (supply of money remaining unchanged).

It means, then, that wage rigidity in the downward direction implies an equilibrium with unemployment existing side by side—if this is so, it will completely falsify the theoretical structure of the classical full employment theory. This shows the importance of the assumption of wage-price downward flexibility in the classical model. In the General Theory, Keynes replaced the classical assumption of a flexible money-wage with that of a rigid money-wage (a more realistic assumption in modern times).

In doing so, Keynes could show the equilibrium could exist with unemployment (called under employment equilibrium). Our analysis given above also shows that this under employment equilibrium is possible even in the classical system reached by Keynes in his theory, provided the assumption of downward flexibility of wages is ignored or waived or the money wage is rigid.

Classical Model with Saving and Investment:

We have seen so far how the classical theory tried to answer the fundamental questions which belong primarily to the realm of macroeconomics: what determines the levels of employment, output, consumption, saving, investment, prices, wages etc.?

The figure below will show the inter-relationship of these propositions along with saving and investment:

1. In part B, the supply (S1) and demand (D1) for labour are both functions of W/P, i.e., real wage. More labour is hired at a lower real wage and more labour is offered at a higher real wage, therefore, supply curve goes up and demand curve goes down. The intersection of the supply and demand curves determines both the real wage (W/P)1 and the level of employment at N1.

2. With techniques of production being given and fixed, output in the short run becomes a function of employment as shown by the production function O in part A with employment at N1.

3. In part C, the price level P is determined by the supply of money (MV) including its stable velocity. The price of output O1 is determined at P1.

4. With equilibrium real wage determined in part B as (W/P)1 and the price level determined in part C as P1—the required money wage is determined in part D as W1.

5. Part E is most important as it shows saving as a direct function of rate of interest and investment and inverse function of rate of interest. Interest rate being the price of capital goods encourages investment when it is low and encourages saving when it is high. The rate of interest itself is determined by the intersection of saving and investment curves and shows how real income is distributed between saving and consumption (Y = C + S) and how production (Y) is distributed between consumption and capital goods or investment (Y = C + I). Therefore, S = I. Thus, equality of S and I is as fundamental in the classical system as it is in Keynesian system, with the difference that this equality is established by the rate of interest in classical model whenever S > I, or S < I, rate of interest will fall or rise to make S = I. It is the equilibrating mechanism.

6. However, another fundamental question still remains to be answered. Will the employment be such as will equate the demand for and supply of labour? Will it be a full employment equilibrium? An answer to these fundamental questions is possible in the affirmative in case we keep in mind the basic assumption of classical system that wages and prices are flexible in the downward direction. In other words, wages fall if there is unemployment of labour and prices fall, if the existing level of output cannot be sold at prevailing prices.

Given this flexibility, automatic full employment conclusion follows logically. These conclusions of the classical theory of employment can be rejected only by rejecting the assumptions on which this theory is based; otherwise, the theory is internally consistent. Hence, the analyses of the salient features of the classical theory of employment with saving and investment; without saving and investment and under condition of rigid money wage.

Concluding Note:

Although Keynes’ gratitude to the classical masters is profound, it will be unfair to deny him the credit that he deserve. After all, “every contributor to any field of knowledge stand on the shoulders of his predecessors. Specialists in any field of knowledge know that no one man ever single-handed invented anything. In a sense there are no revolutionary discoveries” As remarked by Prof. Harris, “Keynesian economics may seem like and may largely be a new plant; and yet its debts to the older economics are quite clear.” Keynesian assumption of the existence of free and perfect competition is truly classical in nature.

In an article which appeared after his death in 1946 Keynes paying tributes to the classicals and warning the younger Keynesian enthusiasts, wrote, “I find myself moved, not for the first time, to remind contemporary economists that the classical teaching embodied some permanent truths of great significance…”

Despite Keynes’ rejection of the neoclassical theory, his system was deeply rooted in it. Keynes’ assumptions of the existence of free and perfect competition and the law of diminishing returns are truly classical in nature. Marshall’s individual demand was a disaggregated image of Keynes’ total demand. Again, aggregate supply was an extension of the optimum output of the firm.

In both the short period predominated and equilibrium was the central problem of economic analysis. We, thus, reach the conclusion that as far as the logical content of Keynes’ theory goes, no revolution has taken place. General Theory, no doubt, marks a milestone, but not a break or a new beginning in the development of economic theory.

According to S.E. Harris, “As a result of Keynes’ work, the classicists will have to check their assumption, pay much more attention to institutional and short-run problems, better integrate the theory of money, income and output, make theory more useful in the area of public policy, be more concerned with general demand, thrift and expectations, and be less certain on the relation of wage-cutting and employment.”

Keynes was perfectly conscious of his debts to the early writers as well as his own contributions. Keynes himself makes pertinent remarks in the preface of the ‘General Theory’. “Those who are strongly wedded to what I call the classical theory will fluctuate, I expect, between a belief that 1 am quite wrong and a belief that I am saying nothing new.” His judgments of the typical shapes of the various functions are indeed revolutionary. No other economist had ever worked out a complete and determined model based on the propensity to consume, marginal efficiency of capital and liquidity preference.