Read this article to learn about the general theory of economics. Below you will find information on (i) The theory are not general; (ii) It is not dynamic; (iii) The equilibrium at underemployment levels is not established; and (iv) It is a depression economics.

The General Theory—It’s Generality:

In his book J.M. Keynes remarks, “I call this book the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, placing the emphasis on the prefix general.

The object of such a title is to contrast the character of my arguments and conclusions with those of the classical theory of the subject.

I shall argue that postulates of the classical theory are applicable to a special case only and not to the general case, the situation which it assumes being a limiting point of the possible positions of equilibrium. Moreover, the characteristics of the special case assumed by the classical theory happen not to be those of the economic society in which we actually live, with the result that its teaching is misleading and disastrous if we attempt to apply it to the facts of experience”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We find that the prefix general has been deliberately used by Keynes for his theory of employment which he developed in this book. It is our endeavor to examine in what sense and to what extent his theory is general vis-a-vis the classical theory which he calls a ‘special case’. In the preface of the book Keynes himself says, “that if orthodox economics is at fault, the error is to be found not in the superstructure but in a lack of clearness and of generality in the premises.” He thinks it important, not only to explain his own point of view, but also to show in what respects his theory departs from the prevailing theory. He says, “those who are strongly wedded to what I shall call” “the classical theory”, will fluctuate, I expect, between a belief that I am quite wrong and a belief that I am saying nothing new'”. He himself held with conviction for many years the theories which he thought of attacking and he was not unaware of their strong points.

The generality of the General Theory lies in the dynamic development—which was left incomplete and extremely confused earlier “Our method of analyzing the economic behaviour of the present under the influence of changing ideas about the future is one which depends on the interaction of supply and demand, and is in this way linked up with our fundamental theory of value. We are thus led to a more general theory, which includes the classical theory with which we are familiar as a special case”.

In other words, generality of the ‘General Theory’ lies in the complete integration of monetary theory with the theory of value. From a monetary theory of money and prices, Keynes shifted to a monetary theory of output. The integration of the theory of money with the theory of value and with the theory of output was attained through the rate of interest the missing link (rate of interest) was at last discovered’.

According to Keynes it was a mistake to imagine that full employment is a part of the natural order of things, and that departures from it are abnormal and temporary, rather, full employment is only one of a number of possible situations—it is in fact, special case. The assumptions of classical economics according to Keynes were applicable to this special case (of full employment) only and not to the general case.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is what he means when he says the situation which the classical theory assumes is a limiting point (full employment) of the possible positions of equilibrium (different levels of the employment). In other words, Keynes theory deals with all levels of employment, whether it happens to be full employment, widespread unemployment or some intermediate level—the purpose of the General Theory is to explain what determines the volume of employment at any given time; in contrast with classical theory, which is concerned with the special case of full employment. Keynes theory is general, therefore, as it can explain every situation whether it be one of full employment, under employment or over full employment.

The classical school assumes that there is tendency for the economic system based on private property and profit motive to be self-adjusting at full employment. Keynes, however, challenges this assumption and calls the classical theory based on it a special theory, applicable to one of the limiting cases of his general theory.

Keynes attempts to show that the normal situation under ‘laissez faire’ capitalism in its present stage of development is a fluctuating state of economic activity which may range all the way from full employment to widespread unemployment, with the characteristic level far short of full employment. Although unemployment is characteristic but by no means inevitable.

Another ‘general’ aspect of the ‘General Theory’ is that it explains ‘inflation’ as readily as it does unemployment because both are linked with effective demand. Inflation is caused by an excess and deflation is caused by a deficiency of effective demand. If Keynes’ more general theory is correct, then the special theory is at fault not only in being the theory of a limiting case but also in being largely irrelevant to the actual world in which unemployment is obviously one of the gravest problem.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Most of the significant differences between the classical theory and Keynes’ theory stem from the difference between the assumption that full employment is normal and the assumption that less than full employment is normal. The one is a theory of a stationary static equilibrium and the other is a theory of a shifting equilibrium.

There is equally another important meaning associated with the term ‘general’ as it appears in the title on Keynes’ book. His theory relates to changes in employment and output in the economic system as the whole in contrast with traditional theory which relates primarily, but not entirely, to the economies of the individual business firm and the individual industry. The General Theory “has evolved into what is primarily a study of the forces which determine changes in the scale of output and employment as a whole”.

All the basic concepts of Keynes’ General Theory are in terms of aggregates of employment, national income, national output, aggregate supply, aggregate demand, total social consumption, total social investment and total social savings. Macroeconomics—a study in aggregates—studies the behaviour of these aggregates over time and space.

According to Prof. K.E. Boulding, “Macroeconomics deals not with individual quantities as such, but with aggregates of those quantities, not with individual income but with national income, not with individual prices but with price level, not with individual output but with national output”. According to James Tobin, “There are two persistent grand themes in macroeconomics. One is the explanation of short run fluctuations some would call them cycles—in business activity, the year-to-year or month-to-month changes that add up to prosperity or recessions, inflation or deflation. The other is explanation of long-run economic trends the rate of progress of an economy over the decades…The theory of long-run growth is essentially a theory of aggregate supply”.

The relationship between individual commodities expressed in terms of individual prices and values—which constitute the chief subject matter of traditional economies—are important in Keynes’ General Theory, but these are subsidiary to the aggregate or overall concepts of income, employment, output etc. A little reflection will show that conclusion which are valid for the individual units may not be valid when applied to the economic system as a whole; for example, a person may grow rich by picking the pocket of another person, obviously the whole community cannot enrich itself merely by its members plundering each other.

Again, a man by willingness to work for less may overcome his own unemployment, but the general unemployment problem of the community as a whole cannot be solved in this way. Prof. Boulding calls these instances ‘Macroeconomic paradoxes’. These paradoxes, according to Prof. Boulding, “are those propositions which are true when applied to a single individual but which are untrue when applied to the economic system as a whole”. There is, therefore, perfect justification in describing the ‘General Theory’ as ‘general’ as it has evolved and developed a separate branch of economic analysis—called macroeconomics. The simple Keynesian model given on next page not only explains the pith and substance of Keynes Theory but also depicts its ‘generality’.

There are three basic equations in Keynes’ model:

(i) National income equals the sum of consumption expenditure and investment (Y = C + I);

(ii) Consumption depends upon income C = ƒ(Y); and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) Investments are given, i.e., they do not depend on the other variables in the model, especially total expenditure, (I = I0).

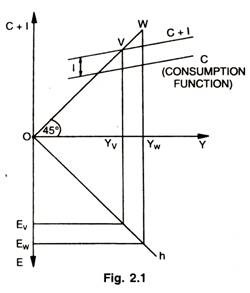

On the horizontal axis national income Y has been shown. This is a money flow; its size is what we want to find. On the top of the vertical axis we measure the sum of consumption and investment. This sum C + I shows the total production of, and outlay on goods and services. In Keynes’ theory C + I and Y are equal, as emerges from the first equation. This first equation is shown in the model by a line which passes through the origin at an angle of 45° to the axes. For every point of this line Y – C + I the point of equilibrium will, therefore, have to lie on this line.

Next consumption function is shown. It is a straight line that intersects the 45° line. At the point of intersection consumption equals Y; at this point, therefore, the whole income is consumed; nothing is saved (and nothing is invested). The economy is ‘stationary’ here, productive capacity docs not expand. Left to the point of intersection capital is eaten into and savings are negative.

Right to the point of intersection the economy begins to save. Savings are shown by the difference between the 45° line and the consumption line. To arrive at total expenditure, the sum invested I must be added to the consumption function. The curve is shifted in an upward direction over a distance I. Thus, we get the total expenditure function C + I. This gives the total expenditure in relation to the national income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The point of intersection v of this total expenditure function and 45° line is the Keynesian point of equilibrium. Here the entrepreneurs receive exactly the sum that they spend on the factors of production, including their profit. There is no reason for the flow of money or goods to expand or contract. The national income has been determined. It is shown in the model Fig. 2.1 by OY1.

No other point can exist (permanently) for it will mean a discrepancy between receipts and expenditures. As such, only one size of the income is possible—the size at which income generates exactly as much expenditure as its own size—income that generates less expenditure than its own size will shrink and income that evokes more expenditure than its size will expand. The circulation is at rest only at v. This is the essence of Keynesian Theory.

However, it is just possible that the size of the income OYv is not related to the community’s productive capacity. It may be smaller than would be possible with the available working force and the level of labour productivity. This is shown in the model by extending the vertical axis downward. On this is plotted E, employment. The relation between E and Y is shown by a straight line h in the fourth quadrant. The productivity of labour which—means national income divided by the quantity of labour used—Y/E determines the slope of this line h.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This line enables us to know whether total expenditure on goods and services does yield a satisfactory national income or not. We draw the perpendicular VYv downwards and move to the left from the point of intersection with the labour productivity line h. We get the point Ev. This is the employment that results from the model. But perhaps this is too small, in the sense that unemployment results. Let OEw represents full employment, the point at which the whole working force is employed (apart from frictional, seasonal unemployment etc.).

Let us return to the Y axis via the h line, we get the national income required for the state of full employment. It is most desirable result that our model could show under the existing circumstances as depicted in the model, employment is too small and unemployment is EVEW. National income is also less: YVYW was not realized—why? Because the total expenditure was too small—being only VYv— whereas to get an optimum national income it should have been WYw. V is thus the false equilibrium; W is the true equilibrium. The false equilibrium—which is cause of Unemployment and small national income, is in turn, caused by C + I having a deficiency of WYw— VYv. We call this the deficiency of effective demand or the deflationary gap.

By assuming a different position of the C + I curve the model would have produced an inflationary gap. Thus, in this model factors have been analyzed which go to determine the national money income. But a number of related problems have also been solved, one of these is the definition of the concepts of inflation and deflation.

The Keynesians speak of true inflation if Y lies to the right of W (i.e. if there is excess effective demand) ; this is truly an inflationary situation. It is, therefore, evident from the model that Keynes’ ‘General Theory’ is not only useful for explaining deflation: depression and unemployment (as supposed by some) but also the same reasoning can serve to describe and to explain inflation.

However, everything depends on the position and the location of the C + I curve. This clearly shows that the basic equation Y = C + I of Keynes theory on which this model is drawn can explain inflation, deflation and different levels of employment and the factors on which full employment at a time depends. Herein lies, therefore the ‘generality’ of the ‘General Theory’

Keynes’ General Theory has had a revolutionary impact practically on all fields of Economics. His monetary theories and recommendations have proved very useful in the solution of major economic problems associated with the Great Depression, the war economy, and the immediate post-war transition, and will doubtless continue to be helpful in meeting our future economic problems.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The details of policy must, however, and necessarily differ from place to place and from time to time, but Keynes diagnosis of the fundamental economic problems of our times has provided us with an objective technique of thinking which transcends any partisan policy discussions—specially in a free society.

If we are to minimise the harmful effects of fluctuations of effective demand and to maintain continuous full employment and output within the framework of the democratic traditions, it is but essential for us to investigate the main determinants and functions of the Keynesian system, namely, the positions and shapes of liquidity, consumption, savings and investment functions’.

The Theory Is Not General?

However, there are others who argue that Keynes’ theory is not general as it fails us as a theory of development or growth. There is no theory of development in the General Theory. They maintain Keynes’ theory is as the most depression economics, it is static, it is short-period economics—it does not apply anywhere and everywhere, it is not applicable in underdeveloped countries—how could it be general then?

Keynes has indeed been blessed with critics. Friendly amongst them attempted to systematize his theory and cut out the dead wood in general to clarify the arguments. Unfriendly critics, however, tried to show that classical economics was not Keynes’ ‘classical economics’; that his assumptions were unjustified ; that building upon these unrealistic assumptions, his theory was unreal and sterile and his practical proposals for policy would destroy capitalism.

It is impossible to list all the criticisms against the ‘Generality’ of the ‘General Theory’ and against the ‘General Theory’ itself. Even then, some economists contend that Keynes, confronted with a leak in the classical house, instead of filling the hole, tried to raze the whole structure—it is another case of burning the house in order to roast the pig.

Such criticisms against the ‘generality’ of the ‘General Theory’ are not justified. It is not proper to say that there is no theory of development in the ‘General Theory’. It is well to remember that Keynesians like Harrod, Domar, Mrs. Joan Robinson and Kurihara have emphasized the implicit dynamic elements in Keynes, and out of his system have constructed a theory of growth. Moreover, Keynes developed a theory of employment which may be regarded as a function of growth. Therefore, it is not proper to deny the ‘generality of the ‘General Theory’ merely because some feel that there is no theory of development in the ‘General Theory’.

Is It A Depression Economics?

Some economists, no doubt, described Keynesian economics as depression economics. They argue that most of the Keynesian functions are active only during depression, then—how can it be general? But this is a wrong charge. It is true that Keynes lived and wrote during depression period. He was primarily concerned with factors which would take the depressed economy of England out of the depth of depression.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It was on account of the peculiar circumstances in which he lived that he wrote a lot about depression and attributed unemployment to the insufficiency of effective demand. We also know that during the Second World War he dealt with the problems of inflation as effectively as he dealt with the problems of depression.

Therefore, it is more appropriate to describe his economics as general economics rather than depression economics. Simply because Keynes analysed the problems of depression and the factors which will bring about full employment during such a period should not make us think that it is depression economics.

It is, therefore, neither necessary nor desirable to describe Keynesian economics as depression economics or to think of Keynes as a depression economist. Hicks was wrong in describing his economies as the economics of depression. A more suitable description would be to describe him as an anti-cyclical, or as anti-deflation and anti-inflation economist. Those who associate his economics with depression conveniently forget his major contributions in his last book—’How to pay for the War’, in which he mentioned about the important measures needed to combat inflation.

It is true that Keynes did much for the Great Depression; it is also true that he did much for inflation also. To realise this, one has to paste certain subsequent Keynesian additions to the ‘General Theory’ and read through his famous work ‘How to pay for the War’ which first outlined the modern theory of the inflationary process.

It is high time that the fallacious belief that Keynesian economics is good depression economics and only that, is given up. On the contrary, his economics is indispensable to an understanding of conditions of over effective demand and secular stagnation. Some have even gone to the extent of remarking the concepts like marginal propensity to consume have validity in times of boom only. “Perhaps, therefore, it would be more nearly correct to aver that certain economists are Keynesian fellow travellers only in boom times, falling off the band wagon in depression”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In fact, Keynes himself is to be blamed for this kind of impression that the ‘General Theory’ is a depression economics. Keynes himself developed a special theory on these forces in the ‘General Theory’. He felt that the propensity to save which, if it is too high, summons up depression and unemployment, would display a steadily rising trend.

There was another reason. One of Keynes’ most influential followers the American Alvin Hansen, developed an alarming theory about the permanent depression. He foresaw not only too great a propensity to save, but also a constant abatement of investments. Population growth would come to a stop, which was supposed to discourage capital outlay.

As such, the entrepreneurs would be disheartened. Hansen’s view was depression economics with a vengeance. This was, however, not due to the logic of the Keynesian system, but to the special premises that Hansen had incorporated in his theory. However, this criticism of Keynes theory is misplaced, for Keynesian logic and its ‘generality’ and the depression theory are two different things.

There is a good deal of substance in Prof. Schumpeter’s thesis that “those who seek universal truths, applicable in all places and at all times, had belter not waste their time on the ‘General Theory’. By general theory, Keynes meant merely theory that dealt with full employment as but a special case. Impressed by institutional changes and considerations, Keynes was impelled to rewrite economics…In his view, Keynes was doing economics a disservice in presenting as universal truths, in the Ricardian tradition………”. He also did not subscribe to the view that Keynes’ medicine is curative only for Great Britain.

Prof. Schumpeter found even more helpful in the American economy, with its institutional rigidities, strong group interests. Keynesian economics applies to hybrid economic societies—partly capitalist and partly socialist—and so long as these societies prevail, Keynes’ economics will serve as very useful guideposts for policy. In a changing institutional set-up, Keynesian economics will have to be adapted and modified; on the same grounds that the General Theory replaces Mill’s Political Economy or Marshall’s Principles of Economics, a newer general theory will ultimately replace Keynes’ General Theory.

Thus, the ‘generality’, of the General Theory lies in the dynamic development of Keynes’ analytical framework, in the integration of the theories of value and money, in studying all levels of employment instead of special case of full employment, in examining the aggregates of the economic system and in studying at the same time inflation and deflation as aspects of effective demand, in denying that it is only a depression economics. The fundamental ideas of the General Theory revolves round the general nature of Keynes’ Theory, the role of money, the relation of interest to money, investment and uncertainty about the future.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We, thus, find that whenever internal economic problems are under Consideration, the classical doctrine of “laissez faire’, the theory of comparative costs, Marx’s materialist interpretation of history, Schumpeter’s thesis of innovations, neo-classical marginal mechanism, do not help us in tackling the problems of unemployment and we have to turn to Keynes’ ‘General Theory’ for a satisfactory solution of the problems till a newer and more general theory will replace Keynes’ ‘General Theory’.