Let us make an in-depth study of the debates over government debt.

Introduction:

When a government spends more than it collects in taxes, it borrows to finance the deficit. The accumulation of past borrowing is the government debt.

All governments have some debt, although the amount varies from country to country. There may be budget surplus and deficit. If a government spends less than it collects in taxes, it pays past borrowing out of the financial surplus.

In recent years, most governments have budget deficits rather than surplus. This experience of budget deficits have sparked a renewed interest among economists and policymakers in the economic effects of government debt. Some economists consider these large deficits as worse mistake of economic policy, whereas others think that the deficits matter little.

Various Views of Government Debt:

The various views of government debt are discussed below:

1. The Traditional View of Government Debt:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynesian model shows that a tax cut stimulates consumer spending and reduces national saving. The reduction in saving raises the interest rate, which crowds out investment, as we have seen above. The Solow Growth Model shows that lower investment eventually leads to a lower steady-state capital stock and a lower level of output since the economy starts with less capital than in the Golden Rule steady-state, the reduction in steady-state capital implies lower consumption and reduced economic well-being.

To analyse the short-run effects of the policy change, we turn to the IS- LM model. This model shows that a tax cut stimulates consumer spending, which implies an expansionary shift in the IS curve. If there is no change in monetary policy, the upward shift in the IS curve leads to an expansionary shift of the aggregate demand curve.

In the short-run, when prices are sticky, the increase in aggregate demand leads to a higher output and employment. Over time, as prices adjust, the economy returns to the natural rate of output, and the higher aggregate demand results in a higher price level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To see how international trade affects our analysis, we turn to the open economy model, which shows that reduced national saving causes a trade deficit. Although, the inflow of capital from abroad lessens the effect of the fiscal policy change on capital accumulation, which implies that the economy becomes indebted to foreign countries.

The fiscal policy change may cause the domestic currency to appreciate, which makes foreign goods cheaper and domestic goods more expensive abroad. The Mundell-Fleming model shows that this appreciation of domestic currency and fall in net exports reduce the short-run expansionary impact of the fiscal change on output and employment. The tax cut financed by government borrowing would have the following effects on the economy.

The immediate impact of the tax cut would be to stimulate consumer spending which affects the economy in both the short-run and the long-run. In the short-run, higher consumer spending would raise the demand for goods and services and, thus, raise output and employment.

Interest rate would rise as investors competed for a smaller flow of saving. Higher interest would discourage investment and would encourage capital to flow, in from abroad, which would appreciate the value of domestic currency against foreign currencies, which would make domestic product less competitive in the world markets.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the long-run, the smaller national saving caused by the tax cut would mean smaller capital stock and a greater foreign debt. Thus, the output of the nation would be smaller, and a greater share of that output would be owed to foreigners.

The overall effect of the tax cut on economic well-being would be difficult to judge. Current generations would benefit from higher consumption and employment, although inflation would likely to be higher as well. Future generations would bear the burden of today’s budget deficit – they would be born into a nation with a smaller capital stock and a larger foreign debt. However, a ‘Ricardian’ would reach a quite different conclusion.

2. The Ricardian View of Government Debt:

Modern consumption theories emphasize that, because consumers are forward-looking, consumption does not depend on current income alone. Friedman’s permanent-income hypothesis and Franco Modigliani’s life-cycle hypothesis are based on the forward-looking consumers. The Ricardian view of government debt applies the logic of the forward-looking consumer to study the impact of fiscal policy.

The Basic Logic of Ricardian Equivalence:

We consider the response of a forward-looking consumer to the tax cut. The consumer may think that as the government is cutting taxes without reducing its expenditure, so it would not increase their permanent income. The government is financing the tax cut by running a budget deficit, which means, at some point in the future, the government will have to raise taxes to pay-off the debt and accumulated interest.

So the policy really means a tax cut today coupled with a tax hike in the future. Thus, the cut merely gives a transitory income that eventually will be taken back. The consumers are not any better off, so they will leave their consumption unchanged. The forward-looking consumer understands that government borrowing today means higher taxes in the future.

A debt-financed tax cut does not reduce the tax burden; it merely reschedules it. It does not raise permanent income of the consumer and, thus, does not increase consumption. The general principle is that government debt is equivalent to future taxes, and the forward-looking consumers are aware that future taxes are equivalent to current taxes.

Hence, financing the government by debt is equivalent to financing it by taxes. This view is known as Ricardian equivalence, named after the famous economist David Ricardo who first noted the theoretical argument.

The implication of Ricardian equivalence is that a debt-financed tax cut leaves consumption unaffected. Households save the extra disposable income to pay the future tax liability that the tax cut implies. This increase in private saving just replace the public saving. National saving remains the same. The tax cut has none of the effects that the traditional analysis predicts.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The logic of Ricardian equivalence does not imply that all changes in fiscal policy are irrelevant. Changes in fiscal policy do influence consumer spending if they influence government purchases as well. For example, suppose the government cuts taxes today because it plans to reduce government purchases in the future, then only consumer will feel richer and raise his consumption. It may be noted that it is the reduction in government purchases, rather than the reduction in taxes, that stimulates consumption.

The Government Budget Constraint:

For better understanding of the link between future taxes and government debt, it is necessary to imagine that, the economy lasts for only two periods — present and future periods. In period one, the government collects taxes T1 and makes purchases G1, and in period two, it collect taxes T2 and makes purchases G2. Since the government can run a budget deficit or surplus, taxes and purchases need not be equal in any single periods

We wish to see how the government’s tax receipts and expenditures in the two periods are related. In the first period, the budget deficit equals government expenditure minus taxes. That is – D = G1 – T1, where D is the deficit. The government finances the deficit by selling an equal amount of government bonds. In the second period, the government must collect enough taxes to repay the debt including interest, and also pay for its second-period purchases. Thus, T2 = (1 + r) D + G2 where r is the interest rate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To derive the equation linking purchases and taxes, we combine the two equations above.

Substituting D from the first equation into the second equation we obtain:

T2 = (1+ r) (G1 – T1) + G2.

This equation relates purchases in the two periods to taxes in two periods.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

After rearranging the terms, we get:

T1 = T2/(1 + r) = G1 + G2/(1 + r).

This gives us the government budget constraint. It means that, the present value of government purchases must equal the present value of taxes.

The government budget constraint shows how changes in fiscal policy today are related to changes in fiscal policy in the future. If the government cuts first-period taxes without altering first-period expenditure, then it enters the next period owing a debt to the government’s bond-holders.

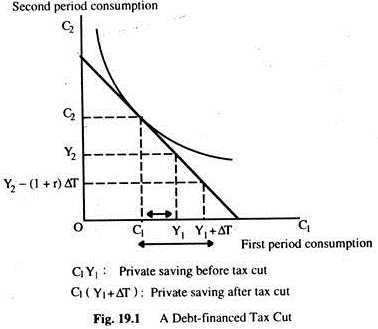

This debt forces the government to choose between raising taxes and reducing expenditure. Fig. 19.1 shows a debt-financed tax cut in the Fisher diagram. The cuts in taxes in period one affects consumer under the assumption that it does not alter expenditures in either period.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In period one, the government cuts taxes by ∆T and finances this tax cut by borrowing. In period two, the government must raise taxes by (1+ r) ∆T to repay its debt together with interest. Thus, the change in fiscal policy raises the consumer’s income by AT in period one and reduces it by (1 + r)∆T in period two.

The consumer’s opportunity set remains unchanged because the present value of consumer’s lifetime income is the same as before the tax changes. Thus, the consumer does not change the level of consumption even after the change in fiscal policy, which implies that the private saving will rise as a result of the tax cut. Therefore, by combining the government budget constraint and Fisher’s model of inter-temporal choice, we get the Ricardian result that a debt-financed tax cut does not change consumption.

Consumers and Future Taxes:

The Ricardian view is that, when people decide their consumption, they rationally look ahead to the future taxes implied by government debt. But how forward-looking are consumers? Those who believe in the traditional view assume that future taxes have very little influence on present consumption as the Ricardian view makes us to believe. Here are some of their arguments.

Myopia:

Supporters of the Ricardian view of fiscal policy assume that people are rational when making decisions about how much of their income to consume and how much to save. Rational consumers look ahead to the future taxes implied by present government borrowing. Thus, the Ricardian view presumes that people have enough knowledge and foresight.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The traditionalists view about tax cut is that people are short-sighted, perhaps because they do not fully comprehend the implication of budget deficits. It is possible that some people follow simple rule of thumb when deciding how much to save. For example, suppose a person assumes that future taxes will be the same as current taxes.

This person will not be able to take account of future changes in taxes implied by current fiscal policies of the government. A debt-finance tax cut will lead him to believe that his permanent income has increased, even if it may not have. The tax cut will lead to lower national saving and higher consumption.

How a Debt-Finance Tax Cut Relaxes a Borrowing Constraint:

The Ricardian view of government debt depends on the permanent income hypothesis, which is that consumption does not depend on current income, but on permanent income, which includes both current and expected future income. According to the Ricardian view, a debt-financed tax cut increases current income, but it leaves permanent income and consumption unchanged.

Supporter of the traditional view argue that we should not rely on the permanent-income hypothesis because some consumers face borrowing constraint. Those who face borrowing constraint can consume only his current income. For this person, current income rather than permanent income determines consumption.

A debt-financed tax cut increases his current income and thus consumption, even though future income is lower. When the government cuts current taxes and raises future taxes, essentially it is giving taxpayers a loan. For individuals who wanted to obtain loan, but were unable to, the tax cut raises consumption.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A debt-financed tax cut raises consumption for a consumer facing a borrowing constraint. A debt-financed tax cut of ∆T raises first-period income by ∆T and reduces second-period income by (1 + r) ∆T. Since the present value of income is unchanged, the budget constraint does not change consumption. Yet, as the first-period income is higher, the borrowing constraint allows a higher level of first-period consumption. Hence, Ricardian equivalence does not hold.

3. Future Generation:

Besides these two arguments presented above, there is a third argument for the traditional view that consumers expect the future taxes not to fall on them, but on future generations. For example, suppose the government cuts taxes today, issues 50-year bonds to finance the budget deficit, and then raises taxes in 50 years to repay the loan.

This means that the government debt represents a transfer of wealth from the next generation to the current generation of taxpayers. This transfer increases the lifetime resources of the current generation, so it raises their consumption. It means that, a debt-financed tax cut stimulates consumption because it gives the current generation the opportunity to consume more at the expense of the future generation.

Economist Robert Barro argued in support of the Ricardian view that because the future generations are the children and grand-children of the present generation, we should not consider them as independent economic actors. Instead, he argues that present generations care about future generations.

This altruism between generations is evidenced by the gifts that many people give their children, sometimes in the form of bequests at the time of their death. The existence of gifts or bequests demonstrates that people are not willing to take advantage of the opportunities to consume more at the expense of their children.

According to Robert Barro’s analysis, the relevant decision making unit is not the individual who lives only a limited number of years, but the family which continues indefinitely. In other words, an individual decides how much to consume not on the basis of his income only but also on the basis of the income of future members of his family.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A debt-financed tax cut may raise the income an individual receives in his lifetime, but it does not raise the permanent income of his family. Instead of consuming the extra income from the tax cut, the individual saves it and leaves it as a bequest to his children, who will bear the future tax liability.

Again, we see that the argument about government debt is really an argument over-consumer behaviour. The Ricardian view assumes that consumers have a long time horizon. Barro’s analysis of the family implies that the consumer’s time horizon is infinite. If, however, the consumers do not look ahead to the tax liabilities of future generations, because they do not care enough about their children to leave them a bequest? In this case a debt-financed tax cut can alter consumption by redistributing wealth among generations.

Making a Choice:

Having considered the traditional and Ricardian views of government debt, we should ask ourselves two sets of questions.

First, which view do you agree with?

How a debt-financed tax cuts affect the economy?

Will it stimulate consumption, as the traditional view holds?

Or, Will it offset the budget deficit with higher private saving?

Second, why do you hold the view that you do?

If you agree with the traditional view of government debt, what is the reason?

Do consumers fail to understand that higher government borrowing today means higher taxes tomorrow?

Or, do they ignore future taxes, because future taxes fall on future generations with whom they do not feel an economic link?

If you hold Ricardian view, do you believe that consumers have the foresight to see that government borrowing today implies more taxes tomorrow?

Do you believe that consumer will save extra income to offset that future tax liability?

One might have hoped that we could turn to the evidence to decide between the two views. Yet, when economists examine historical episodes of large budget deficits, the evidence is inconclusive. For example, let us consider the experience of the 1980s. The large budget deficits seem to offer a natural experiment to test the two views of government debt.

At first glance, this episode appears to support the traditional view. The large budget deficits coincided with low national saving, high interest rates, and a large trade deficit. Indeed, advocates of the traditional view of government debt often claim that the experience of the 1980s confirms their position.

However, those who believe in the Ricardian view of government debt interpret the events of the 1980s differently because people were optimistic about future economic growth. Or perhaps, saving was low because people expected that the tax cut would not lead to higher taxes but to lower government expenditure. Because it is hard to rule out any of these interpretations, both views survive.

Can the Budget Deficit be Correctly Measured:

The disagreement between the traditional and Ricardian views of government debt is only the source of controversy. Even economists who hold the traditional view argue among themselves about how best to evaluate fiscal policy.

Other disagreement among the economists is about the measurement of budget deficit. Some economists believe that the current measurement of deficit is not a good enough indicator of the stance of fiscal policy. They believe that the budget deficit does not accurately measure either the impact of fiscal policy on the economy today or the burden being placed on the future generations. Here we discuss three problems with the usual measure of the budget deficit.

The general principle is that the budget deficit should accurately measure the change of government’s overall indebtedness. This principle is not difficult at all. But its application is not so simple as one might expect.

Measurement Problem Number One: Inflation:

There is unanimity among the economists that the government’s indebtedness should be measured in real terms, not in nominal terms which means that the measurement issues need the correction for inflation. The measured deficit should equal the change in the government’s real debt, not its nominal debt.

The budget deficit normally does not correct for inflation. This induces large error in the measurement of debt. The following example will give us some idea. Suppose, the real government debt is not changing in real terms, the budget is always balanced. But the nominal debt must be rising at the rate of inflation. That is – ∆D/D =П, where П is the inflation rate and D is the stock of government debt. This implies ∆D = ПD.

The government would look at the change in the nominal debt ∆D and would present a budget deficit of ПD which most economists believe that the reported budget deficit is overstated by ПD. In other words, the deficit in government expenditure minus government revenue.

Part of government expenditure is the interest paid on the government debt. Expenditure should include only the real interest paid on the debt, rD, but not the nominal interest paid, iD. The difference between the nominal and the real interest rate is the inflation rate, П, the budget deficit is overstated by ПD. This correction for inflation can be large, especially when inflation is high, and it can often change one’s evaluation of fiscal policy.

Measurement Problem Number Two: Uncounted Liabilities:

Many economists believe that the measured budget deficit is not accurate, because it does not include some important government liabilities. For example, consider the pension of civil servants. These civil servants provide services to the government today, but part of their compensation is deferred to the future. Their future pension benefits represents a liability to the government not very different from other government debt. But this accumulated liability is not included as part of the budget deficit of the government.

Similarly, consider the Social Security System which is not significantly different from a pension plan. People contribute some of their income into the system when young and expect to receive benefits when they are old. Thus, accumulated future Social Security benefits should also be included in the government’s liabilities.

One might argue that Social Security Liabilities may not be regarded as government debt, because the government can always change the laws determining Social Security benefits. Yet the government could always choose not to repay all its debt; the government honours its debt only because it decides to do so. To pay the holders of government debt may not be fundamentally different from promises to pay the recipients of Social Security benefits.

A special form of government liability is to measure the contingent liability — the liability that is due only if a special event occurs. For example, if the government guarantees some form of private credit, such as student loans, mortgages, etc. If the borrower repays the loan, the government may not have to pay anything; if the borrower defaults, the government may have to make repayment. When the government provides this guarantee, it undertakes the responsibility to repay the debt if the borrowers default. This contingent liability is not reflected in the budget deficit.

Measurement Problem Three: Capital Assets:

Some economists argue that an accurate measurement of budget deficit requires accounting for its assets and its liabilities. In making particular measure of the government’s overall indebtedness, we must exclude government assets from its debt. Thus, the budget deficit should include the change in debt minus the change in assets.

Assets and liabilities are treated simultaneously by firms and individuals. For example, when a person borrows to buy a house, we do not consider his liability only. Instead, we should consider his assets (house) against his liability (mortgage) and record no change in net wealth. Perhaps we should treat the government’s deficit in the same way.

A budget procedure that treats both assets as well as liabilities is called capital budgeting, because it takes into consideration changes in capital. For example, suppose the government privatizes its companies or sells its land or office building to reduce its debts. Under present budget procedures, the reported deficit would be lowered.

Under capital budgeting, the revenue received from the privatisation of government assets would not lower the deficit because the reduction of debt would be offset by a reduction in assets. Similarly, under capital budgeting, government borrowing to purchase a capital asset would not increase the deficit.

The main difficulty with capital budgeting is that it is difficult to decide which government expenditures should be included as capital expenditure.

For example, should the stockpile of nuclear weapons be considered as an asset?

If so, how to evaluate these weapons?

Should spending on education be treated as expenditure on human capital?

To adopt a system of capital budgeting, these difficult questions must be answered by the government, Economists and policymakers do not agree about whether or not the system of capital budgeting should be used by the government. Opponents of capital budgeting argue that it may be a better method than the current system, but it is too difficult to implement in practice. Those who support capital budgeting hold that even an imperfect treatment of capital assets would be better than ignoring them altogether.

Whether the Budget Deficit:

Economists differ about the importance of these measurement problems. Some believe that the problems are really very important. Most consider these measurement problems seriously but still view the measured budget deficit as a useful indication of fiscal policy.

The important lesson is that, to evaluate fully the course of fiscal policy, economists must look at more than just the measured budget deficit. In fact, they do. The budget documents prepared annually contain much detailed information about the government’s finances.

Conclusion:

Fiscal policy and government debt have been central to political debate in many countries over the past decade. As we have seen, economists disagree about how fiscal policy affects the economy and how fiscal policy is best measured. These are among the most important and disputed questions facing policymakers today. We are confident that these debates will continue, as long as fiscal deficit continues!