Everything you need to know about human resource management process. Success of any organization depends on the management of human resources.

It is the responsibility of HRM to convert the human resources into skilled and quality human resources and for this a proper process should be followed to recruit, select, train and place human resources in any organisation.

Human resource management process is a systematic process of managing people working in the organization.

Human resource management is a managerial process of acquiring and engaging the required workforce, appropriate for the job and concerned with developing, maintenance and utilization of work force.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this article we will discuss about human resource management process. The overall process of HRM includes the following steps:- 1. Recruitment, Selection and Placement 2. Training and Development 3. Counselling 4. Job Evaluation 5. Merit Rating, Promotion, Transfer, and Demotion.

Human Resource Management Process: Recruitment, Selection, Training, Placement, Promotion, Transfer and Demotion

Human Resource Management Process – Top 4 Steps Involved in the Process of Managing Human Resource

Step # 1. Recruitment, Selection and Placement:

Recruitment and selection of a new employee is an important personnel function. The selection involves two basic steps – (i) the tapping of sources of supply, and (ii) the interviewing or picking out from among potential candidates. The sources of supply for procuring manpower are present and former employees, friends and colleagues, public and private employment agencies, advertising schools and colleges and casual applicants.

The establishment of the National Employment Service in 1945 has helped in improving the methods of recruitment. Employment Exchanges have been set up under this service. All fresh employments in Government, Quasi-Government and Local Bodies, as also private enterprise are required to make use of these Exchanges.

i. Interview:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

After a prospective candidate appears for employment, the second step, in selection by “sizing up” the candidate is taken by interviewing him and by reference to testimonials and recommendations, if any. Every interview should be conducted frankly in a straight forward manner. This applies to both parties. It should not be hurried, but should be sufficient in length to put the candidate at his ease, so that he may reveal himself in his natural state by talking of himself and his previous employment, if any.

Sometimes a second interview may be necessary to properly appraise a candidate. The interview should also supply information about the job and the company for which the applicant is to work.

The interview will be followed by certain mental and trade tests for placing the worker in the organisation. The tests which have been used with profit for this purpose are- Intelligence Tests for measuring intelligence or scholastic aptitudes; Interest tests for finding out the candidate’s likes and dislikes for different occupations; Aptitude tests, designed to measure a number of native abilities not concerned with “intelligence”; and Personality tests which relate to the subject’s social life, relations with his family, emotional reactions, etc.

A word of caution is called for. Too much reliance in selection should not be placed on psychological techniques and tests which seem to be fast growing; and the majority of which are of questionable value. It is not intended to imply that all the methods are useless, but they must not be regarded as anything like a complete and fool proof solution to the problem of selection. After a person is selected, he should be sent for medical examination. Medical examination is beneficial both to the employee and the employer.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is axiomatic that selection should be on the basis of merit without any other consideration, but a number of pressures are often applied from within and outside the organisation. The task of matching the man to the requirements of the job becomes very difficult.

The fundamental principle of selection that we must fit a man to the job and not the job to the man has been ignored. Very often, because of certain pressures, a man is appointed but then no one knows what to do with him. Perhaps a job is created or modified to fit him.

Another aspect of selection is the extent of participation of the Personnel and Line Officers in the selection procedure. It varies from organisation to organisation. The line officer may assess the suitability of the candidate from the functional angle. The personnel man plays a more important role to see that the person selected will fit in the group in which he is expected to work, has the ability to get along with others and to ensure that the rules and regulations prescribing the standards for recruitment are uniformly and meticulously observed.

ii. Guidance and Placement:

Selection of right men for given tasks is only the first step in securing an efficient working force. After employment the new employee should be courteously and intelligently dealt with in the matter of placement. He has to be helped and guided in deciding what he can do best of all possible chances open to him.

Modern industry is becoming increasingly aware of the importance of placing on every job an individual who is not only able to do the job well but who, in addition, is temperamentally adapted to the job in question. An individual is best adapted and is usually most satisfied, when he has found an outlet for whatever energy, drive and ability he may possess.

Each position should be filled by one who wants it. One who knows he is “better off” in it than in any other place he can find. Misfit and dissatisfied men are burdens. It is better to have each position filled by a man who is barely competent to fill it than to have it filled by a man who should have a much better position.

Step # 2. Training and Development:

Training is a corner-stone of sound management. Employees must be systematically trained if they are to do their jobs well. New workers must be taught to do the job correctly from the outset; channels ought to exist to teach old employees new methods as they are developed. A training programme gives management an opportunity to explain carefully and clearly its policies, rules and regulations.

Tangible results of a training programme include reduction in labour turnover, less spoiled work, less damage to materials and equipment, and improvement in quality and quantity. Above all good will is generated, as in the final analysis, training programme is a reflection of management attitudes.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There are two general approaches to instruction:

i. The Absorption Method, and

ii. Intentional Method.

i. Instruction by absorption leaves men on their own to sink or swim. Sometimes an older employee may be assigned to take an interest in the new employee, but usually left to learn himself by trial and error, by watching others and asking questions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. Instruction by intention is the planned method of training new men. In the ideal situation every step in learning the job by the new employee has been planned in advance. The learner is given every opportunity to develop as rapidly as possible and is encouraged at every step.

The following training methods have enjoyed widespread use namely:

i. On-the-job training.

ii. Off-the job or training centre training.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iii. Apprenticeship training.

i. On-the-Job:

On-the-job, training takes place in the department on the equipment where the employee will work. It is suited for teaching relatively simple production and clerical operations to new employees. It is also used when job methods are significantly changed or when an employee is transferred to a different job.

When employees are trained on the job they get the feel of actual production conditions and requirements. The trainees learn rules and regulations and procedures by observing their day-to-day application. The management can size up trainees.

ii. Off-the-Job or Training-Centre:

Off-the-job or Training-Centre training is providing by schools or centres (the Americans call the Vestibule Schools) established by the young persons in specified trades.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Training can also be provided by experienced fellow-workers. This type of training is particularly adaptable where experienced workmen need helpers. It fits in well also in departments where workmen advance through successive jobs to perform a series of operations.

Training by supervisors provides the trainees opportunities for getting acquainted with their bosses and the supervisors have good chances to judge the abilities and possibilities of trainees from the job performance point of view.

iii. Apprenticeship Training:

Apprenticeship training aims to develop all-round skilled craftsman. The major part of apprenticeship-training is done on the job doing productive work. Each apprentice is given a programme of assignment according to a pre-determined schedule. The well-balanced programmes provide for efficient training in trade skills and permits a sufficient amount of time for the training to the apprentice to mature as a responsible worker and then a supervisor.

Step # 3. Job Evaluation:

Job evaluation is the rating of jobs according to specific planned procedure in order to determine the relative worth of each job. It is a systematic method of appraising the worth or value of each job in relation to other jobs in the company. Job evaluation rates the jobs, not mm, or women on the jobs, which is the task of employee rating. The principles of job evaluation can be applied to all kinds of employees, operatives as well as executives.

They can be applied to businesses of all sizes. The sole purpose of job evaluation is to divide up any given pay roll so that all jobs are paid according to their relative difficulties. For example, the job of a machinist and that of an electrician may appear to be quite different, but if they are of the same relative difficulty, requiring similar skill, effort and intelligence, both would be paid at the same rate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Job evaluation is useful in many ways; and with a job evaluation plan in operation, inconsistency in rates is minimised and the entire wage structure becomes unified. According to Knowles and Thomson, job evaluation is useful in eliminating many of the evils to which nearly all systems of wage and salary payments are subject.

These are – (i) Payment of high wages and salaries to persons who hold jobs and positions not requiring great amounts of skill, effort and responsibility; (ii) Paying beginners less money than they are entitled to receive in terms of what is required of them; (iii) Giving raises to persons whose performances do not justify them; (iv) Deciding rates of pay and increases in pay on the basis of seniority rather than ability; (v) Payment of widely varied wages and salaries for the same or closely related jobs and positions; and (vi) The payment of unequal wages and salaries because of race, sex, religion, and political differences.

Step # 4. Merit Rating and Promotions, Transfer and Demotion:

Merit Rating:

Merit rating are concerned with the relative worth of men – as measured by certain specific techniques. These techniques, which are formalised procedures for differentiating among or assessing workers, are usually referred to as merit rating plans, employee-rating plans or performance rating.

Merit rating may be defined as a systematic evaluation of an employee’s performance on the job in terms of the requirements of the job. The merit-rating systems are used by firms primarily because each supervisor must differentiate among his subordinates. He has to decide which employee to recommend for promotion, for layoff, for wage increases, or for special training. Thus, his job involves making judgments about people. A good supervisor bases his judgment on a systematic approach – merit rating, rather than rely on rule of thumb, intuition and other less systematic procedures.

It is appropriate to recognise at the outset that employees are rated for a number of different reasons. Therefore, the subject of merit rating covers more than wage and salary administration. It is even regarded as a technique for improving communication and building esprit de corps. The specific uses of merit rating vary from firm to firm.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Merit rating is used for the following purposes and reasons:

i. Merit rating is most commonly used to justify wage increases, but it has many other industrial-relations uses.

ii. It is used as a part of the selection process itself in deciding whether employees on probation are to be confirmed or not.

iii. It helps the supervisor in the task of job placement in line with the individual employee’s personal peculiarities.

iv. It helps in identifying employees who deserve promotion and those who should be transferred to some other job where he is likely to perform more efficiently.

v. It acts as a criterion to be used by the employment office to judge the effectiveness of its own selection.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

vi. It can be used as part of a seniority system for layoff purposes. Where ability and length of service are considered as a part of seniority, merit rating can be of great assistance.

vii. Merit rating may be used as a part of the employee’s disciplinary record to protect the employee, the supervisor and the company from discrimination, favouritisms, or charges of such unfair practices.

Merit rating is, thus, used to give employees an idea of how they are doing, identify promotable employees, award wage adjustments, improve supervision, discover training needs, guide selection and placement, and comply with union contracts.

In spite of its usefulness, merit rating is opposed by many employees. A part of this opposition arises from a basic distrust of anyone in authority, and a part of it arises from a sincere questioning of the ability of the supervisor to judge accurately the abilities and performance of the employees. For this reason managements go to great lengths to secure uniformity among the various raters as well as objectivity as far as possible. Certain forms and certain procedures aid in securing uniformity in evaluation.

Promotions and Transfers:

The fundamental principle of employment, which every employer should keep in mind, is to put on a job the best possible man obtainable for the money he is prepared to spend, no matter where he comes from. Very frequently, however, the knowledge of the firm and its methods possessed by “insiders” will make them more suitable for the higher posts than any outsider could be.

Therefore, every employer should make an efficient effort to produce his own skilled workers, and should plan to fill higher positions, as far as possible, by promotions and transfers. Undoubtedly, doors should not be barred to outsiders, who may bring valuable new ideas, and save the firm they join from going to sleep, but the “discards” of the other plants should be avoided.

Ordinarily, the demand made upon the outside labour market should be for beginners only, unless some specially qualified outsider fits better than any of the insiders. After all, ambitious employees are anxious for promotional opportunities.

A promotion is the transfer of an employee to a job that pays more money or one that enjoys some preferred status. The job evaluation, by means of analysis as to their requirements, and merit rating showing capacities of individual workers, will open natural lines of transfers and promotions. Transfers enable the management to check up its own mistakes in the selection or placement of workers.

Every man is good for something and the business of the employment department is to find what that something is. The proper remedy for a misfit is usually a transfer, and not a discharge. Transfers stimulate the labour force as much as promotions, for they are an evidence of regard for the individual worker. Promotions are transfers to higher pay and better work for the merit; the making of them stimulates employees to earn merit.

Promotions are the proper answer to the argument that an employee must not do his present work conspicuously well or he will always be held upon it. A promotion by leaving a position vacant creates an opportunity for a stimulating series of promotions below it. This acts as a satisfying recognition of the logical claim that the opportunities within an establishment belong to those who are members of its labour family rather than to outsiders.

To facilitate promotion, positions should be arranged like the steps of a stairway or the rungs of a ladder, so that each place is a preparation for the next higher one. It was Frank Gilbreth who conceived what he called the Three-Position Plan according to which all the positions throughout an establishment are to be placed together by functions of teaching and learning.

He described this plan thus “The three positions are as follows; first and lowest, the position that the man has last occupied in the organisation; second, the position that the man is occupying at present in the organisation; third, and highest, the position that the man will next occupy. In the first position the worker occupies the place of the teacher, this position being at the same time occupied by two other men, that is, by the worker doing the work who receives little or no instruction in the duties of that position except in an emergency, and by the worker below who is learning the work. In the second position the worker is actually in charge of the work, and is constantly also the teacher of the man next below him, who will next occupy the position. He is also, in emergencies, a learner of duties from the man above him. In the third position, the worker occupies the place of learner, and is being constantly instructed by the man in the duties of the position immediately above”.

It is, however, not enough to construct stairways or ladders; they must be kept open. “An officer who stagnates, blocks a line below him, and leaves a place above without a candidate in reserve”. Therefore, a promotion programme must be kept alive by promoting men for merit, and never for pull or favouritism.

Seniority may at times be given weight, but seniority alone is as bad a basis as pull or favouritism. Promotions based upon merit awaken ambition; and each promoted person becomes a symbol of what may be attained by another. In such a system each subordinate is a sort of standing challenge to his superior.

Demotions:

Opinions differ with regard to the demotion of an employee. Some managers hesitate to demote a man on the theory that he will not be satisfied to take the lower job and it is therefore better to discharge him than to have a disgruntled employee. This attitude is especially true with regard to executives.

There is some merit to this way of thinking; yet many a worker, especially an executive, would be only too happy to be removed from a job that he recognises he is unable to fill as it should be filled, provided that this can be done without too much shock to his personal pride. Often, such men should be transferred to another job or section, where he may be a success. The man, who has failed, is not always solely responsible for his failures. His superiors have erred in judgment as well as he.

If a man, who has reached a position, after successfully filling various positions over a period of 20 years, and finds himself incapable of handling the job fully successfully, he may ask to be permitted to revert to his old job; provided the situation is properly handled. Such adjustments require a high type of personnel administration. Discharge is the easy way but not necessarily the sound one.

The management should prepare the men for stepping down and not merely handle the occurrence as a matter of course. Demoted workers or supervisors have a psychological adjustment to make. Attention to this matter is a mark of real leadership and pays dividends in helping people when they really need it. You may not be able to avoid altogether some heartaches in demoting an employee, but you can minimise them.

Withdrawals and Dismissals:

The Personnel Manager’s part’ in dealing with –

i. Retirements;

ii. Terminations;

iii. Redundancy at Retirement;

iv. Dismissal –

(a) For disorderly conduct, or (b) for unsatisfactory work, is the complement of his tasks in recruitment, training and promotion.

i. Retirements:

Retirement of a worker is an important event in his life; and from the company’s standpoint it turns on the morale value. At the time of parting the Personnel Manager (in a smaller firm, the owner) should arrange a special interview with the employee. The firm’s policy makes this the occasion for a souvenir presentation. In any case, it should be made clear to the employee that the company is still interested in him and always ready to help him.

All legal obligations to him may have ceased, but where a man has given a major portion of his working life to a firm, they have a moral duty to extend a considerate and helping hand to him. They undoubtedly draw benefit from this contribution, for such an attitude adds to the morale of all employees in the firm.

ii. Terminations:

Termination of service of one employee or another for some reason may have to be made at one time or other – This involves a task with two distinct phases. There is the purely routine task of seeing that the departing employee is paid his dues, returns tools or equipment belonging to the firm, gets back his insurance card, and so on. But there is also the human side, the face-to-face contact with the employee by the Personnel Manager or his deputy.

Not long ago, employees could be dismissed at a day’s notice or none at all, without regard to the personal damage done to the individual by the shattering of security, to the morale of the factory or office, or to the fabric of society. But today the existence of a personnel policy usually guarantees against unfair dismissal. The Personnel Manager sees that the guarantee is upheld and the employee is given fair chance to explain before he is asked to quit.

He must also see that the employee leaves with a sense of justice done rather than injustice suffered, and that his former mates do not bear a self-justified resentment. On the other hand, an employee may want to leave either because he is dissatisfied with the conditions of service or unfair treatment, or because he is getting married and leaving the district or for some other genuine reason.

Where a worker’s leaving reflects discontentment, the Personnel Officer should see to it that the weakness in organisation or supervision is removed, and if possible, the good employee is retained.

iii. Redundancy:

Redundancy of operators may occur because of the completion or cancellation of contract or other outside economic factors and retrenchment of usually the last employees to join may become necessary. If retrenchment is to be on a considerable scale, the detailed work needs to be carefully planned beforehand. In every case, the employees should be given adequate notice or pay in lieu of notice, so that they have the opportunity of seeking another employment.

The shop stewards (foremen or head jobbers) should be taken into confidence, and reasons for retirement explained at the outset. Ordinarily, the principle of “last come, first go” should be observed.

iv. Dismissal:

Dismissal for disorderly conduct must always be based on some definite evidence. It may be a breach of the rules, a brawl or fight between two employees, the merits of which must be gone into by the Personnel Manager, before discharge is ordered. Ample opportunity must be given to the employee to explain his side of the case.

In highly emotional cases, including drunkenness, it is wise never to make a decision on the day the incident happens, but to wait until the next day. People who are giving an account of what has happened will give an entirely different story when they are cool, calm and collected, than they will when tempers are frayed.

Dismissal for unsatisfactory work may have to be made by the Personnel Officer on complaints received from a department. He usually handles this type of case by seeing the man to explain that his work has been unsatisfactory over a long period, and that he has had several warnings, despite these, no improvement has been shown, and finally it has been felt that he must go.

But if the employee protests and challenges certain facts as incorrect, the person who made the allegations must be asked to repeat them in the presence of the employee. Hearing the facts on both sides, the Personnel Manager will have the final word, but it is much better to get agreement from the worker that he has been unsatisfactory and that it is a logical thing for him to be discharged as he has not improved.

It is also a good policy to pay an employee who is discharged (whether from factory or office) wages in lieu of notice rather than ask him to work out the notice and be a misery to himself and everyone else. But when it comes to the end, try to discharge him in a friendly way; there is no need to be hostile, abrupt or unkind. The fact that he has not been successful in one company is no criterion that he will not be an outstanding success in the next. He may well be helped to obtain a suitable job elsewhere.

Human Resource Management Process – 6 Step Process: Recruitment, Selection, Counselling, Training, Promotion & Transfer and Demotion

Step # 1. Recruitment:

It is very important for an industrial concern to be adequately staffed. Systematic steps have to be taken to ensure that the right types of persons are available to the concern in right numbers.

In a country like India which suffers from large-scale unemployment in urban areas and under-employment in rural areas, numbers may not pose a big problem; but it will surely take some time and attention to find out persons who are not merely willing to work but are also suitable for the positions lying vacant. It goes without saying that the management should, to begin with, attempt to make an estimate of the requirements of labour in the different departments.

The number of workers required by a concern depends upon:

(a) The scale of production,

(b) The degree of mechanization, and

(c) Methods of work.

The management must, therefore, keep a watch on developments in these fields so as to be able to take advantage of new techniques of production and new machinery. These days, when it is difficult to get rid of surplus labour owing to the operation of various labour laws, it is necessary that no surplus worker is recruited in the first instance.

In short, the management will do well to draw up a plan for the recruitment of labour for the coming year or so. The plan may be thoroughly scrutinized before steps are taken to recruit labour. There are various methods of recruiting labour. Recruitment should be conducted in an organised manner preferably by the personnel department.

The personnel department will obviously keep in mind the requirements of various departments both as regards quantity and quality. But, in small concerns where there is no personnel department, the departmental managers themselves recruit people for their respective departments.

The following are the chief methods of recruiting labour:

1. Recruitment at the Factory Gates:

In a country like ours where there is a large number of unemployed people, it is not rare to find job-seekers thronging the factory gates. Whenever workers are required, the foreman or the departmental manager scrutinises, in a general way, the people who are available at the gate and recruits the necessary number. For obvious reasons, this method of recruitment can be used safely only for unskilled workers.

A variation of the system is to maintain a register of what are known as ‘badli’ workers. If this register is used to recruit casual workers in place of the regular workers who happen to be absent, the badli workers would go to the factory gate almost every morning to find out whether their services are required for the day or not. If there is a permanent vacancy, recruitment may be made from amongst the badli workers.

2. Recommendations of the Existing Employees:

In order to encourage existing employees, some concerns have made it a policy to recruit further staff only from the relatives of their existing employees. It may be provided that other conditions being equal preference will be given to the sons and brothers of the existing employees.

3. Advertising the Vacancies:

Usually this is not done for recruiting unskilled workers, but this is the usual method for recruitment of skilled workers, clerical staff and for higher staff.

4. Employment Exchanges:

Employment bureaus or exchanges are quite common in foreign countries. In India, the employment exchanges were established only after the Second World War for the resettlement of Ex-Servicemen. At present, however, the employment exchanges are open to all citizens, and everybody can utilise the services of the exchange for obtaining a job.

It is not compulsory yet for the private employers to use the employment exchanges for recruitment of their workers, but the Government is considering a proposal to make it compulsory for them to do so. Employment exchanges can obviously help in the recruitment of all sorts of workers and employees except perhaps the managerial staff.

But quite often, the exchanges are not able to supply all the requirements of a concern and consequently a concern may be forced to resort to other methods of recruitment. Further, the exchanges are not yet equipped to screen various candidates and, therefore, the employer has himself to find out whether the candidate recommended by the employment exchange would be suitable for work. It will be helpful if employment exchanges make their own arrangements for assessing the qualities and capacities of the candidates, so that the employers find some advantage in using their services.

5. Direct Recruitment from Colleges and Universities:

This practice is prevalent for the recruitment of higher staff in western countries where there is a great shortage of highly qualified administrative and technical personnel. In India, this practice has yet to be adopted on a large scale. Only a few big progressive concerns, like Hindustan Lever, have arrangements for drawing upon the talent available in universities.

One of the prominent features of the modern factory system is the shifting nature of the labour force. When some workers leave a concern, others take their place. Thus there is not only a movement of labour out of individual concerns but also a corresponding number of new persons joining them.

Labour turnover refers to the changes which occur in the ranks of workers in a concern over a given period. The rate of labour turnover, therefore, indicates the extent to which the composition of the labour force undergoes changes.

Such rates can be divided into two broad groups:

(а) Accessions, i.e., the employment of new workers or the re-employment of former workers, or the additions to the ranks of the workers; and

(b) Separations, i.e., termination of employment, or the departure of workers.

Separations can be of the following types:

(i) Quits refer to workers leaving on their own accord. Workers may themselves decide to leave their concern owing to job dissatisfaction, acceptance of other jobs, ill-health or some other personal reasons,

(ii) Discharges, i.e., the dismissal of workers from service by the employer on account of violation of rules, dishonesty, disobedience, laziness, habitual absenteeism, etc.,

(iii) Lay-offs, i.e., suspension of workers owing to lack of adequate work or shortage of materials.

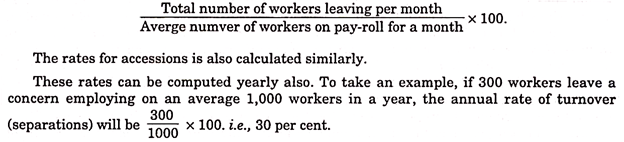

The rate of separations will be found as follows:

It should be noted that a high rate of labour turnover means a heavy drain on a concern. It tends to be wasteful in the following ways:

(i) Loss of output – There is a direct loss of output because (a) the vacancy may take some time to fill up, (b) the new worker may take quite some time to pick up the work, and (c) the other workers may take some time in adjusting themselves to new recruits.

(ii) Training cost – The time and expense incurred on the selection and training of the worker quitting the concern will go waste.

(iii) Under-utilisation and mishandling of equipment – The newly employed worker may not be able to utilise the equipment to the fullest extent, and may be responsible for breakage of equipment and wastage of materials during the training period.

(iv) Increased selection costs – The management will have to spend afresh on the selection and training of new employees to replace those who leave it.

(v) Added overtime – Regular workers may have to be paid overtime in order to make up the deficiency caused by the new, inexperienced worker under training.

(vi) Low team-spirit – Above all, the ‘team-spirit’ among workers and the reputation of the concern will suffer.

Step # 2. Employee Selection:

It is of utmost importance that the right type of men should be put on different positions in a concern. This is well expressed by the proverb that ‘for round holes there should be round pegs, and for square holes there should be square pegs.’ If a job is handled by a person who is so well qualified that he can be put on a better job, he will develop a grouse against the management and society in general for being made to work below his capability.

He will also be dissatisfied because his earnings will be much less than what he would be able to get if he were to do the job suited to his capacity and capability. From the point of view of the employer also, it will not be worthwhile to employ such a worker because he will tend to be inefficient for want of interest.

If the job is given to a person who is not properly qualified for it, it may not be done well and again there will be a loss for the employer. The employee will also develop a sense of inferiority. In both cases, both the employee and the employer suffer. Ultimately, the worker may find himself an utter ‘misfit’ and may decide to leave the concern.

Or else the concern may have to dismiss him on account of poor workmanship. This will lead to high labour turnover. The quality of work is also likely to be adversely affected in this process.

It is, therefore, necessary that a job should be done by a person who is exactly qualified for it—no more and no less. This is the essence of a sound policy of personnel employment. To ensure the selection of the right type of persons for various jobs, the techniques of psychology may be applied in a systematic manner.

When workers are selected for vocations or jobs in an industrial concern after a careful weighing of the requirements of jobs on the one hand and assessment and evaluation of the abilities and aptitudes of men on the other, it is referred to as Scientific Vocational Selection.

It will be appreciated that vocational selection requires two things- first, knowledge regarding the qualities or traits which a person should possess in order to do a given job properly; secondly, the measurement of qualities possessed by a candidate for the job. The first task requires the drawing up of a ‘job specification’.

A job specification may be defined as a catalogue of various qualities which a person doing a job should possess. It is based on an analysis of the character of an industrial operation known as ‘job analysis’ or ‘occupational analysis’.

The following are the broad headings under which the qualities desirable for a suitable candidate may be grouped:

1. Educational and technical qualifications.

2. Intelligence and dexterity.

3. Health and physique.

4. Responsibility involved and initiative required.

5. Ability to command and obey.

6. Personality.

7. Ability to work in the conditions in which the job is performed.

These qualities are required in various measures for different jobs. A person, who is not fit for one job, need not, therefore, be necessarily unfit for all. This fact is recognised under scientific vocational selection and an attempt is made to find out whether the candidate is suitable for the job concerned or not.

The job specification is drawn up with the help of the people who are getting work done by workers and with the co-operation of psychologists or other people who know how the minds of workers work. For this purpose, the character of an industrial operation may be analysed by the job analysts and a detailed description of the job (called job description) may be prepared.

The job description includes- (i) what the worker does in a particular job, (ii) duties and responsibilities of the worker, (iii) location of work and equipment used, (iv) working conditions, (v) training and education needed, (vi) hours of work, and (vii) opportunities for promotion.

As has been mentioned above, the job specification will be based on job description so as to give the interviewer an understanding of the job and the qualities necessary for its performance when a prospective worker is before him.

A concern which cannot make a detailed job specification should nevertheless attempt to list the broad qualities required for various jobs. It is only then that proper staff can be recruited and the problems of square pegs in round holes can be avoided.

The main purpose of a proper procedure of recruitment and selection being to find the right man for each job, the exact procedure will depend upon the job for which appointment is to be made. For jobs involving responsibility and decision-making, the procedure is necessarily elaborate.

For ordinary workers in a factory, the procedure would be rather simple. The old practice of entrusting the task of selection to the foreman or some other official who is not well versed in the techniques of scientific vocational selection is now being gradually replaced by a more efficient system of selection by a central employment department.

The employment department should be manned by psychologists and technical experts and should select workers and employees for all departments.

(а) Requisition:

The first step in the direction of employing people is requisitioning of workers by the supervisor in whose department vacancies arise. A requisition should state clearly the number of workers required and should be accompanied by the relevant job specification.

(b) Recruitment:

The next step will be for the employment department to write to the employment exchange or advertise the vacancy in the newspapers asking the candidates to send applications giving their qualifications or tap some other source of labour.

On receipt of applications from candidates or names from the employment exchange, the recruitment office should eliminate the candidates who are obviously unqualified for the job and prepare a list of candidates who are eligible for the job.

(c) Application Blanks:

The selection of workers is the next step involving a more careful screening of the potential candidates from the lists already prepared. For this purpose, a form is sent to the candidates who are qualified. The form must be designed to elicit full information about the candidate particularly with regard to his educational qualifications, his experience, his interests, etc. It should ask for definite information.

A candidate should be asked to state how he has been employed during the past five or ten years with reasons for any change of jobs. This will show whether this candidate is of a type who sticks to one job or is one likely to give up a job on a flimsy ground. Some concerns have the practice of asking candidates to come for interview and fill up ‘blanks’ then and there.

When forms are filled up in this way, they have one important advantage. The candidate may give information which is contrary to what he gave in his original application. An explanation of the discrepancy will probably throw some light on this character and personality.

Filling up the application blank provides fair opportunity to those who do not feel at ease in the interview but can write down their answers without any hesitation. A few candidates are generally invited for personal interview.

(d) Trade Tests:

In case of jobs which involve technical work, a trade test is generally required. For recruitment of a stenographer in an office, a test can be given to check up his speed both at dictation and typing. Workers for a factory can be given similar tests (i.e., trade tests) to find out their capabilities for the type of job for which they are being considered.

(e) Psychological Tests:

Acting on the principle that individuals differ from one another by degree though not in kind, industrial psychologists have devised certain tests which seek to measure the psychological characteristics of individual applicants for a position. A psychological test is an objective and standard measure of a sample of human behaviour.

It consists in giving to the applicant a task which is representative of the job for which he is being considered. His performance on the task is evaluated relative to that of the other candidates. There are different types of tests standardised for jobs at different levels.

Some of the important tests used in industry are:

(i) Intelligence tests, i.e., tests which measure the mental capacity of a person to grasp and put together the elements of a novel or abstract situation.

(ii) Aptitude tests, i.e., tests to measure the aptitude of applicants which is their capacity to learn the skills required on a particular job.

(iii) Interests tests, i.e., tests to determine the preferences of an applicant for occupations of different kinds.

(iv) Dexterity tests, i.e., to determine an individual’s capacity to use his fingers and hands in industrial work.

(v) Achievement tests, i.e., tests of the level of knowledge and proficiency in certain skills already achieved by the applicants.

(vi) Personality tests, i.e., tests designed to judge the emotional balance, maturity and temperamental qualities of a person.

(f) Interview:

The purpose of the employment interview is to find out the candidate’s mental and social make-up and to know whether the qualities possessed by him make him suitable for a job in the concern. The purpose of the interview is definitely not to confuse the candidate and, so to say, to defeat him.

Therefore, it must be conducted in a friendly atmosphere and the candidate must be made to feel at ease. If the candidate receives a warm and cordial welcome, it will leave a lasting impression on his mind. He may be enthused to work well for the concern if he gets a chance to work there.

At the interview, questions should better be asked on the basis of job specifications, although questions arising out of the candidate’s answers should not be ruled out. If questions are asked in a haphazard manner, the candidate may feel that no justice has been done to him and nothing of value may be found about him.

Matters like hours of work, rest period, work on holidays and overtime should be carefully explained. So far, the employment interview is considered to be the most satisfactory way of judging temperamental qualities of the candidates. In fact, in some concerns, it is the only tool of selection.

This method, however, suffers from two chief drawbacks- (i) some abilities and qualities cannot be assessed through an interview; (ii) it banks too much on the personal judgment of the interviewer. Nevertheless, the interview is positively useful if it is supplemented by other devices and techniques of selection.

(g) Medical Test:

No worker should be selected without a medical test. This is important because a person of poor health may generally be absent and the training given to him may go waste. A person suffering from any disease may spread it amongst other workers. In any case even if a person does not suffer from any disease, the requirements of a job may be so exacting that a person of poor physique may not be able to handle it properly. For example, if a worker is required to handle heavy materials, he must possess sufficient physical strength to do that.

(h) On-the-Job Test and Selection:

It is on the basis of the results of these various tests that the candidate would be finally selected but before he is given a job on permanent basis it would be better to try him out for a few weeks in the factory itself. This is because no procedure of selection can find out the whole reality about the personality of the selected candidates.

It is only by observing workers actually at work that one can find out how they behave with their fellow-workers and supervisors. Even a competent man may, sometimes, not be able to work harmoniously with his colleagues. If this is so, obviously such a worker is a misfit and needs to be put to some other Job.

By observing a candidate at work it will be known whether he can do his job properly or not. Therefore, it is only after a trial for a few weeks that the person concerned should be treated as finally selected. If a person is not found suitable, the management may transfer him to some other job to which he may be expected to do better justice, but, if the organisation cannot offer him a job which he can do well, the management will do well to sack him promptly.

If an unsuitable person is made permanent, it will be a cause of dissatisfaction both to the management and to the employee for all time to come. The management will be dissatisfied because the person cannot do his job well and the employee will be dissatisfied because he will not get any further promotion.

Step # 3. Vocational Guidance or Counselling:

It has been pointed out above that for each job, the right type of man should be selected. The task of filling jobs with the right sort of people is known as vocational selection. This is obviously important from the point of view of the employer. But, what is equally important is that a person should also have the job which suits him.

The task of guiding a person as to what sort of job he should have is known as vocational guidance. Therefore, vocational selection and vocational guidance are two sides of the same coin, namely, the task of fitting men on jobs. The procedure is almost the same in case of vocational guidance.

As the first step, the psychologists obtain particulars of the scholastic attainment and proficiency from the teachers, and the opinions and wishes of the parents about the young people under examination. An analysis of the occupations which they may adopt is undertaken with a view to finding out the factors necessary for success at these jobs.

The psychologists may, then give psychological tests to the candidates. Of these, intelligence tests are designed to indicate the mental calibre of the candidates and on the basis of their results some jobs are dropped from consideration as being higher or lower than the candidate’s general mental level.

Aptitude tests may be administered to find out the special mental and manipulative abilities of the candidates for the jobs for which their suitability is being considered. Personality tests may be given to ascertain their temperamental tendencies and their general ability to get along well with others.

The reports on the health and fitness of the candidates should also be considered. On the results of these tests, a few jobs will remain for consideration. At this stage, the candidate’s own preferences may also be ascertained. Thus may be found a job which, on the whole, is less unsuitable for a candidate than others.

To take an example, psychologists may find a young man well suited for an engineering job. But his financial resources may not be adequate to enable him to pursue a course of study for such a job. The right type of guidance in such a case would also take into account the financial position of the candidate.

An important aim of vocational guidance is to direct the candidate to a job at which he can make the best possible use of his talents and which does not require any particular quality or qualification which he does not possess. To be really useful, vocational guidance should be available to young men before they begin their specialised education. In India, such education begins in the 9th class in higher secondary schools.

The task of vocational guidance has been traditionally done by parents and teachers. But parents and teachers usually do not have a detailed knowledge of the numerous openings available to young men, even when they may have proper knowledge about their children. Therefore, it is necessary that the task of vocational guidance is handled by experts.

Step # 4. Training:

Having selected the most suitable persons for the various categories of jobs in the concern through the application of scientific techniques, it becomes necessary to arrange for their training. While education improves the knowledge and understanding of employees in a general way, training aims at increasing the aptitudes, skills and abilities of the workers to perform specific jobs.

With increased chances of a new worker doing well at his job, the systematic methods of vocational guidance and selection are extended to their logical conclusion. A person, however capable and competent, cannot do his best at a job unless he is systematically trained in the correct methods of work. The advantages of a training programme are obviously numerous.

In the first place, training brings about an improvement of the quality and quantity of output by increasing the skill of the employees. A novice, who has just started working without proper training, will normally produce less than another person who has been systematically trained. In fact, the quality of work done by him may not be up to the mark for lack of proper training.

Secondly, trained personnel will be able to make much better and more economical use of materials and equipment than untrained employees, thus reducing the cost of production.

Thirdly, since trained personnel will commit very few mistakes, the management can well afford to focus its attention on planning the work and encourage expert workers.

Fourthly, training also helps in spotting out promising men and in locating mistakes in selection. The promising trainee will naturally be discovered from his quick understanding of instruction. An unsuitable trainee, on the other hand, will show absolutely no interest in training for the job concerned.

Lastly, training will create a feeling among the workers that they are being properly cared for, and that the employer is sincere to them. This will improve relations between the employers and employees.

If, on the contrary, the workers are not fully trained in the correct methods of work, unwholesome developments may follow. The level of output and the quality of work may be poor. Untrained workers may develop a feeling of dissatisfaction towards their jobs and may leave the concern quite frequently and in large numbers, making for a high percentage of labour turnover with its attendant evils.

Thus, if an employer thinks that he is saving some money by dispensing with a training programme for workers, he is highly mistaken. He is unknowingly losing at least the same amount of money as would be required in conducting a training programme without deriving its positive advantages.

Training programmes may be arranged by industrial concerns for different specific purposes.

Accordingly, training of workers may be of the following types:

1. Induction Training:

Induction refers to the initial training provided to workers on their admission to an organisation. The object of such training is to introduce the worker to the organisation and familiarise him with it. Under such a programme, therefore, the worker may be given a general idea about the products manufactured by the organisation, the history of the organisation and its rules, working conditions, etc.

2. Job Training:

Such training is provided to workers with the object of increasing their knowledge about their respective jobs as also of enhancing their efficiency. It enables the workers to know the correct methods of handling the equipment and materials at their jobs. Since the workers have to undergo training in all the processes connected with their job, they can avoid the accumulation of work at vital points (i.e., bottlenecks) and can take necessary precautions against the possibilities of accidents.

3. Training for Promotion:

In most of the organisations, at least some of the vacancies are filled through promotion from amongst existing workers. This provides encouragement to workers to work for promotion. Before, however, workers are promoted to occupy superior positions in the organisation, it is necessary to provide some training to them so that they are well prepared to shoulder their new responsibilities.

4. Refresher Training:

Workers may be formally trained for their jobs in the-beginning when they are put to work. But with the passage of time, many of the methods and instructions may be lost sight of, or forgotten. Refresher training is meant to revive them in the minds of the workers through short-term courses.

The following methods are usually adopted by industrial concerns to provide training to their employees:

1. On-the-Job Training:

Under this method, the worker is put on a machine or a specific job in the factory. He is instructed by an experienced employee or a special supervisor. No special school has to be opened for the trainees and in the course of their training; they continue to add to the output. Usually, the experienced workers acting as instructors have neither the time or inclination nor the competence to provide suitable instruction to the trainees.

The method can, therefore, be successful only if the trainers are well qualified and show enough interest in the trainees. In fact, it was used during World War II to train a large number of unskilled and semi-skilled workers quickly. A common version of such training is “three-position plan”. Under it, a worker learns from the man above him and teaches the man below him.

2. Vestibule Training:

A vestibule is a fore-court or entrance hall through which one has to pass before entering the main rooms in a house. In vestibule training, therefore, the “workers are trained on specific jobs in a special part of the plant.” An attempt is made to create working conditions which are similar to the actual workshop conditions.

After training workers in such conditions, the trained workers may be put on similar jobs in the actual workshop. This enables the workers to secure training in the best methods of work and to get rid of initial nervousness. This method, too, was used to train a large number of workers in a short period of time during World War II. It may also be used as a preliminary to on-the-job training.

3. Apprenticeship Training:

This method of training is in vogue in those trades, crafts and technical fields in which a long period is required for gaining proficiency. The trainees serve as apprentices to experts for long periods, say, seven years. They have to work in direct association with and also under the direct supervision of their masters.

The object of such training is to make the trainees all-round craftsmen. It is an expensive method of training. Besides, there is no guarantee that the trained worker will continue to work in the same organisation after securing training. The apprentices are paid their remuneration according to the apprenticeship agreements.

4. Internship Training:

This method of training refers to a joint programme of training in which the technical institutions and business houses co-operate. The object of such co-operation is to provide such training as will bring about a balance between theory and practice. For this purpose students may be sent to factories for practical training in between their terms at their schools. The chief drawback of such training consists in the fact that it usually lasts over a long period of time.

5. Learner Training:

The ‘learners’ are those who join industry for semiskilled jobs without any prior knowledge about the elements of industrial engineering. They have, therefore, to undergo a programme of education and training. For this purpose, it may become necessary to send them to vocational schools for some time for the study of arithmetic, workshop mathematics and learning operation of machines. After this they may be assigned to regular production jobs.

Training is imparted to supervisors also through conferences, seminars, lectures and discussions on problems of supervision. According to the ‘Position Rotation Plan’, supervisors may work in different positions by rotation.

Step # 5. Promotions and Transfers:

The term promotion is used to refer to the advancement of an employee to a better and higher job. In other words, an employee can be said to have been promoted when he is put on a job which involves higher responsibility, requires a great degree of skill, commands more prestige and a higher status, and carries a higher rate of pay than his previous job did.

Promotion is a means of filling up vacancies which occur in any organisation from time to time. Instead of employing fresh persons in these vacancies, some persons already working in inferior positions may be moved upwards. This will naturally give the employees a hope and faith in their prospects in the organisation.

They can put in their best with an eye on promotion within the organisation. In the absence of such prospects of advancement in the organisation, the employees are liable to get frustrated and show signs of discontent. Such a feeling of dissatisfaction among the employees is fatal to the organisation.

The usual ‘trouble makers’ among the employees are those who are discontented and cannot find enough scope for the use of their talents. It has usually been found that if such persons are promoted to better and higher jobs, they can find satisfaction in their work and can work for the benefit of the organisation.

Thus promotions create a sense of loyalty to the organisation among employees, and give the feeling that their work is receiving due appreciation from the management. The employees may thus be encouraged to work for promotions which will mean better conditions of work, opportunities of an improvement in their standard of living, better status, recognition and the satisfaction that they are turning their abilities to good use.

Similar purpose can be achieved through an upgrading of workers. Upgrading may be described as an increase of pay on the same job. It is promotion on a relatively smaller scale.

For reasons mentioned above, it is imperative for sound personnel policies to provide for promotion and upgrading of employees. But it should not be taken to mean that all vacancies occurring in an organisation should be filled up through promotions. If that is done, the organisation would be shutting itself out to the new ideas which the fresh blood from outside may bring along with it.

The concern may, therefore, stagnate or deteriorate. It is important for the management of an industrial organisation to recognise the two methods of filling up vacancies, namely- (i) promotions within the organisation, and (ii) recruitment and selection of suitable persons from outside. A concern attempting a fine blend of these two methods can hope to have the best of both the worlds.

Basis of Promotion (Seniority Vs. Merit):

Now arises the question of a suitable criterion for promoting employees within the organisation. The management is usually inclined to place a premium on ability of the person under consideration while unions appear to favour seniority or length of service as the sole basis for promotion.

Seniority is an objective basis for promotion. If it is adopted, the management will enjoy no discretion in this matter and everybody in the organisation will know for definite his place in order of importance. There will be no, or at least fewer, disputes about promotion. Also, if employees are promoted on seniority, it will develop a sense of loyalty to the organisation among them.

Seniority has particular significance in India where age and experience are respected by tradition. But if workers are promoted to higher positions merely on the basis of the length of service, it is likely to have an adverse effect on the output. Besides the young brilliant members of the organisation will feel frustrated and may either leave or become indifferent.

Those who are about to be promoted on the basis of their seniority are apt to take work lightly because decline in efficiency cannot mar their chances for promotion. Others who are rather low in the seniority list will lose interest in their work because any amount of enthusiasm in work will not help them in securing promotion.

As such, it will not be advisable to adopt seniority of service as the only basis for promotion. On the other hand, if ability is the sole consideration for promotion, standards of judgment are bound to vary from individual to individual. A particular worker may appear to be abler than the rest in the opinion of one supervisor but may not be up to the mark in the eyes of other supervisors.

The trade unions are usually quite touchy about the adoption of ability as the basis of promotion. They see in this basis a convenient opportunity for the management to abuse its powers and indulge in favouritism and nepotism on the pretext of being guided solely by consideration of ability.

The management, on the other hand, would usually prefer to base promotions on merit. Naturally then a worker who makes a better and more substantial contribution to the output deserves a better place in the organisation. If promotion depends upon merit, it will be the endeavour of everybody in the organisation to work for it.

In this will lie the welfare both of the organisation and of its employees? Owing to the personal character of the judgment about the relative merits of individual workers, however, it will not be fair to adopt merit as the sole criterion of promotion. A sound promotion policy, therefore, takes into account not only the respective merits of the workers but also other important considerations like length of service, physical health, etc.

According to Paul Pigors and Charles Myers, “Seniority should be considered, but only when the qualifications of two candidates for a better job are, for partical purposes, substantially equal.”

In actual practice, a sound promotion policy should include the following elements:

1. The management should clearly state its intention of filling up vacancies in senior positions through promotion from within.

2. There should be an understanding between the workers and the management that promotions will be made on the basis of ability and seniority considered together.

3. Charts showing job requirements in terms of ability, experience, education, etc., should be drawn up on the basis of job analysis. This will enable the workers to know how a job would lead to a superior job.

4. Scientific plans of rating the workers, i.e., assessing their relative worth on the basis of an evaluation of their performance, should be devised to consider the claims of workers for promotion.

5. Recommendation regarding promotion should be made by the immediate supervisors of the workers or their departmental heads to the top management who should take the final decision in this regard. The top management will, however, be well advised to consult the Personnel Department on this point.

6. Promotion should be made for trial periods. If a promoted person is found below the mark during the period of probation, he should be reverted to his previous job.

7. Adequate provision must be made for training for promotion.

Transfers:

Transfer is the movement of an employee from one job to another without involving any significant change in duties, responsibilities, required skill, or compensation. The general nature of duties and responsibilities attaching to new position remain the same, though there may be some change in their specific nature.

Transfers may have to be made within an organisation for varied reasons. Accordingly, there are different types of transfers. If transfers are made to meet the need of the company, they may be termed as production transfers. When a particular department is faced with pressure of work, its strength may be supplemented through transfer from other wings.

A replacement transfer is the transfer of a senior employee to replace a junior employee when the latter is laid off (i.e., the company cannot provide work to him and temporarily sets him aside). Versatility transfers are those which aim at giving the employees varied experience in all different departments. Both of these are types of production transfers.

Personnel transfers are, on the other hand, those movements of the workers which are made primarily to meet the needs of employees. Such transfers are made when a worker has not been placed on the job to which he is best suited. Thus, if a worker does not do well at one job, a transfer will serve his and the company’s purpose better than an outright dismissal.

In fact, the chief use of transfers lies in the fact that they can be used to remedy and rectify mistakes of placement. Transfers of employees may also be made for reasons of health or because of general personal difficulties owing to which the employee is not well adjusted to the organisation.

Demotion is the reassignment of a lower level job to an employee with delegation of responsibilities and authority required to perform that lower level job and normally with lower level pay. Organisations use demotions less frequently as it affects the employee’s career prospects and morale.

The term “demotion” has negative connotation as it implies the reverse of upward mobility and refers to the lowering down of the status, pay and responsibilities of an employee. Thus, a demotion is a downward assignment to an employee in the organizational hierarchy. It is a downgrading process and is insulting to an employee. Demotion is the opposite of promotion.

Dale Yoder defines Demotion “as a shift to a position in which responsibilities are decreased. Promotion is, in a sense, an increase in rank and demotion is decrease in rank.”

Demotion is used as a punitive measure; it is a punishment for incompetence or mistakes of serious nature on the part of an employee. Some managers are reluctant to demote an individual. They prefer to discharge him rather than to demote him on the lower job because he will not accept the lower job and will turn to be a disgruntled employee and difficult to tackle. When an employee is demoted, his pride suffers a more severe jolt than it does when he is superseded by his junior.

Demotion becomes necessary due to several factors, both organizational and employee-oriented:

i. When adverse business conditions force an organization to reduce its manpower the organization may decide to lay-off some and downgrade other jobs.

ii. When departments are combined and jobs eliminated, employees are often required to accept lower-level position until normalcy is restored. Such demotions are not a black mark against an employee.

iii. When a promotee is not able to meet the demands of the new job, he feels inadequacy in terms of job performance and may request to revert to the old job. Besides, some other factors may be a marginal wage rise with increased responsibility, frequent transfers or tours on the new job.

iv. When there is a mismatch between the promotee’s ability / interests and the new job requirements, alternative job could be provided through demotion.

v. When the employee has lost his capacity to work, for instance, if he has become permanently disabled, he should be adjusted within the organization on humanitarian grounds.

vi. When it is essential to take disciplinary action against erring employees, demotion may be a useful tool.

Demotion of an employee for disciplinary reasons (e.g. as a penalty for insubordination or misconduct) should be a last resort decision since it is a severe penalty just short of discharge. It is an extreme step, not merely in terms of loss of pay and status for the employee, but more significantly, for its psychological effect on the employee in particular and others in general.