Market Structure and Imperfect Competition (With Diagram)!

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 1. Subject-Matter:

A perfectly competitive firm faces a horizontal demand curve at the going market price. It is a price-taker.

Any other type of firm faces a downward-sloping demand curve for its product and is called an imperfectly competitive firm. An imperfectly competitive firm must know that its demand curve slopes downward and that its price will depend on the quantity produced and sold. It cannot sell as much as it wants at the going market price.

A pure monopoly is an extreme case where the downward-sloping demand curve of the firm is the industry demand curve? Here we distinguish between two intermediate cases of a monopolistically competitive industry and an oligopoly.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An oligopoly is an industry with only a few firms, each recognizing that its own price depends not merely on its own output but also on the actions of its competitors. Here we begin with monopolistically competitive market which is in a way similar to a perfectly competitive market in that there are many firms, and entry of new firms is not restricted.

But it differs from perfect competition in that the product is differentiated — each firm sells a brand or version of the product that differs in quality, appearance, and each firm is the sole producer of its own brand.

The amount of monopoly power it has depends on its success in differentiating its product from those of other firms. For example, soft drinks, toothpaste and detergent, etc. are monopolistically competitive industries. A monopolistically competitive industry has many sellers producing close substitutes for one another. Each firm has only a limited ability to affect its output and price.

For example, car industry in most countries are oligopolistic. The price that Ford can charge for its cars depends not only on its own production and sales, but also on the decisions taken by major competitors such as Vauxhall, Datsun, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The corner grocer’s shop is a good example of a monopolistic competition. Its output is a subtle package of product such as jars of coffee, personal service and extra convenience for those customers who live nearby.

These last two features may allow the corner shop to charge a few pence more for ajar of coffee than the supermarket at the centre of the city. But if the prices are substantially higher, even shoppers who live nearby will make a trip to the supermarket.

As with most definitions, the lines between these types of market structure are a little blurred. The main reason is the ambiguity about the relevant definition of the market. Is British Rail a monopoly in railways or an oligopoly in transport? It is very difficult to remove such ambiguities.

Similarly, when a country trades in a competitive world market, even the sole domestic producer may have little influence on market price. We can never fully remove these ambiguities.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 2. Oligopoly Behaviour: Collusion and Competition:

Monopoly power and profitability in oligopolistic industries depend, in part, on how the firms interact. If the interaction tends to be more cooperative than competitive, the firms could charge prices well above MC and earn large profit. In some oligopolistic industries, firms do cooperate, but, in others, firms compete aggressively, even though this means lower profits.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To understand why, we need to know how oligopolistic firms decide on output and prices. These decisions are complicated because each firm must behave strategically when making a decision, it must consider the probable reaction of its competitors and, thus, introduce some basic concepts of gaming and strategy.

We examine another form of market structure called cartel; where some or all firms explicitly collude — they cooperate their output levels and prices to maximise their joint profits. A cartel may seem like a pure monopoly. But a cartel differs from a monopoly in two respects.

First, cartels rarely control the entire market. Second, members of a cartel are not part of a big company. They often may be tempted to “cheat” their partners. As a result, many cartels are uncertain and short-lived.

Airlines are examples of oligopoly. Large airlines as British Airways, Air India, Air France and TWA each face a downward-sloping demand curve for their own product, but the position of that demand curve depends on the behaviour of other airlines in business.

When Laker began operating cut-price fares between London and New York in the mid- 1970s, the low fares attracted some new passengers to transatlantic flights. However, many Laker passengers would have flown on other airlines had there been no Laker.

As Laker began to succeed, other airlines were forced to cut their prices to restore their market shares. Thus, they induced an inward shift in Laker’s demand curve. In this price war, Laker went bust first. The other airlines then raised their fares again!

Thus, there is constant tension between competition and collusion in an oligopoly.

Collusion is an explicit agreement between existing firms to avoid competition with each other.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Laker price competition provoked retaliation from other airlines which temporarily reduced all airline profits and Laker itself was made bankrupt. That is the pressure of collusion. But each airline wants to improve its own position at the expense of others.

That is the pressure to compete. Laker could not calculate correctly how other airlines would respond. The essence of oligopoly is to anticipate correctly reaction of its competitors as a result of its own action.

Initially, we did not take into consideration the possibility of new entry into the industry. Legal prohibitions may make new entry impossible. Alternatively, existing producers may have a permanent cost advantage over potential entrants. Having examined oligopoly behaviour when the possibility of entry can be ignored, we then examine how the threat of entry may affect the behaviour of exiting firms.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 3. Profits from Collusion:

The existing firms want to maximize their joint profits and behave as if they were a multinational monopolist. A monopolist would organise the output from each of the plants in the industry to maximise the total industry profit. Hence, if the few producers in an oligopolistic industry agree to get together and behave as if they were a monopolist, they must maximise their total profit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

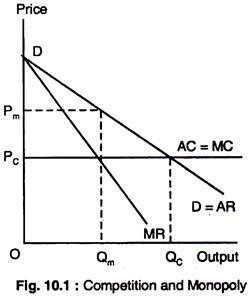

Fig. 10.1 shows an industry with constant AC and MC at the level PC. The industry demand curve is DD. A competitive industry would produce QC at price PC but a multi-plant monopolist would produce Qm at price Pm. Whereas the competitive industry would make no super-normal profits, the monopolist will make maximum possible supernormal profits. Thus, if the oligopolists reach a collusive agreement, they can realize the full potential for the maximum monopoly profit for the industry as a whole.

If this is achieved, at price Pm, we say that the oligopolists are acting as a collusive monopoly. But they will have to negotiate among themselves about how to divide up these profits. However, it is difficult to stop individual oligopolists cheating on their collusive agreement to maintain a collusive monopoly.

Joint profits rise because the industry output is restricted and the price is forced up. Yet each firm can expand output at MC = PC. If one firm expands output slightly by violating the agreed price, Pm, it can increase its own profits since its MR > MC.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Although, by cheating, an individual firm can increase its profits, the profits of the industry as a whole must be reduced by such behaviour. We know that total industry profits are maximised by behaving as a collusive monopoly and setting all prices at Pm.

Hence, one firm can gain by a lower price but its rival must suffer. But each firm has an incentive to cheat and attempt to increase market share and profits at the expense of its rivals. And, in trying to get a larger share of the cake, such cheating will reduce the size of the cake to be shared out by inducing firms to move away from the collusion monopoly solution.

The tension between collusion to maximise the size of the cake and compete for its share is now clear. In arguing that a single firm would gain by slightly reducing price from Pm provided other firms do not follow suit, incentive to cheat can be reduced if they agree at the outset that a price reduction by one will be matched by other firms.

If each firm understands that it cannot increase its share of the cake by undercutting its rivals, then, all firms will have an incentive to maintain the Pm and enjoy supernormal profits.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, explicit collusion was common. Such practices are outlawed in many countries. Although there are usually large penalties for being caught, informal agreement and secret deals still occur in many industries.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 4. Bertrand Model:

Such cheating can be stopped if every firm believes that a price cut will be immediately matched by other firms, only then the collusive agreement may succeed and the monopoly price, Pm, may be achieved. The Bertrand Model examines that opposite belief about competitors’ reactions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Suppose there are two firms A and B who begin by charging the monopoly price P Each believes that cutting its own price-will lead to no price change by its competitor. Thus, each firm believes that a small price cut will enable it to take all the demand currently supplied by its competitor.

Firm A believes that its own demand curve is highly elastic at price Pm. MR is close to price and well above Pc and MC. It can cut price and expand output. At this new price, the firm B makes the same calculation. It cuts the price a bit more and temporarily expands its output until A retaliates. This process ends when the competitive price, Pc, is reached and a further price cut by either firm would lead to loss by both firms.

Thus, the Bertrand Model may not describe actual oligopoly behaviour but it can usefully be contrasted with the case of perfect collusion. Given one extreme assumption about competitor, reactions may be enforceable, and the monopoly price, Pm, will be the industry equilibrium.

Given the opposite extreme assumption about competitor’s reaction — no matching price cut — the competitive price, Pc, will be the long-run industry equilibrium.

Now, we see the usefulness of the two extreme models of perfect competition and pure monopoly. The actual equilibrium position of an oligopolistic industry is likely to lie between these extremes but its exact position will depend on the assumptions that each firm takes about its competitor’s reaction.

The collusive monopoly model leads to monopoly solution, whereas, the Bertrand model leads to the perfectly competitive outcome. But other assumptions about competitor’s reactions lead to intermediate positions. Thus, the industry will make more than the zero profit of a competitive solution, but less than the maximum profit a collusive monopoly can achieve.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 5. Cooperation between Oligopolists:

Unless it is possible for one firm to increase its market share permanently at the expense of the other firms, the long-run profits of each oligopolist will be highest when they successfully collude to charge the monopoly price. We now consider cooperative policies in detail.

Cartels:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Cooperation between firms is easiest when the agreement is explicit and also legally permitted. Such an agreement is called cartel. For example, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is a cartel. Its 12 members meet regularly to set price and output levels. At the moment there is hardly any cheating among its members.

OPEC increased the oil price substantially in 1973 and again in 1979. OPEC revenues increased 340% in real term between 1973 and 1980. After the first oil price shock, many economists predicted that it would collapse like most before it.

Usually the incentive to cheat is too strong for members to resist and other firms follow suit when they discover it. The success of OPEC stems from the fact that Saudi Arabia played a dominant role as shock absorber for the actions of other cartel members. It acts like a dominant firm which determines price and output for the group as a whole.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 6. OPEC and the Dominant Firm Model or Price Leadership Model:

Suppose an oligopolist industry has a dominant firm and a competitive fringe of firms selling as much as they wish at the going price. The dominant firm is large enough to influence price and output through its own actions.

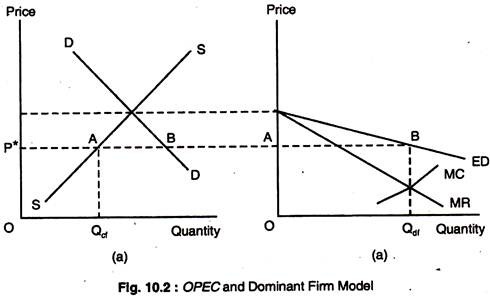

Fig. 10.2(a) shows the demand curve, DD, for the industry and the supply curve, SS, for the competitive fringe as a whole. In oil industry, the competitive fringe has a rising long-run supply curve since oil fields have very different extraction costs. It takes higher prices to make it profitable to exploit higher-cost fields in OPEC and non-OPEC countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At each price, the fringe firms produce as much as they want and are on their supply curve. The dominant firm meets excess demand at each price. Thus, Fig. 10.2(b) shows the dominant firm’s demand curve as ED, the difference between DD and SS at each price such as P* where AB must be the same in both figures.

Facing a demand curve ED, the dominant firm produces output Qdf where MC = MR. The price is P*, the competitive fringe is happy to produce Qcf and the market clears.

Saudi Arabia’s willingness to maintain the cartel has kept OPEC together. Since other countries can produce as much as they wish at the agreed price, there is little incentive for OPEC members to cheat. Saudi Arabia would accept the residual demand ED after the fringe had produced as much as they wanted at the given price.

Thus, Saudi Arabia would not try to produce a higher output than the residual demand ED implied. In return, Saudi Arabia was allowed to fix the price and choose at which point on ED it wished to produce. It set the price P* to achieve an output at which MC = MR. This bargain partly explains the inherent tensions at OPEC meetings.

The supply curve of fringe slopes upward because it requires a higher price to make it profitable to exploit high-cost wells. However, higher prices yield larger profits to those with low-cost wells. Hence, the competitive fringe tended to want a higher price than Saudi Arabia wished.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Saudi Arabia was able to counter this pressure by threatening not to accept ED as its residual demand curve. By producing at a price-quantity combination ED, Saudi Arabia can reduce the quantity available to other members. Generally, other members preferred Saudi Arabia to take a dominant role and set the price provided she then produced at the appropriate point on ED.

After 1980, new oil discoveries and a resumption of production in Iran and Iraq shifted the supply curve of the competitive fringe to the right. Simultaneously, the world recession shifted the demand curve for oil to the left and, thus, Saudi Arabia’s demand curve ED shifted far to the left.

Its output fell sharply and so did oil prices. Thus, its ability to impose discipline on other OPEC members began to weaken and the cartel began to show signs of breaking up.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 7. Implicit Agreement: Price-leader:

When explicit price agreements are illegal, firms often find ways to cooperate implicitly. Such agreements require two things a method of communicating the agreed price to all firms in the industry, and a way of checking that firms are not cheating by undercutting implicit price agreement. One way to communicate the implicit price is for one firm to take the role of the price-leader.

A price-leader is a firm whose price changes are the signals for other firms to follow suit. The price-leader judges when to change the price and the other firms follow the leader and all prices change together without any explicit agreement.

This model is a good example of price behaviour in the cigarette industry and in petrol- filling stations. In both cases, a large number of brands or outlets are controlled by a few companies. Sometimes we find an initial move by the price-leader which is not followed by the rest of the industry and the movements are reversed. Sometimes other members follow suit and the new price sticks.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 8. Conditions Favourable to Cooperation:

Collusion between firms is easiest when it is legally permitted and when profits are not threatened by the entry of new firms to the industry. Licensing arrangements are one way to control entry.

For example, if professional bodies of doctors, lawyers, accountants, etc. can control examination requirements, standards and licences, they would be able to regulate the flow of new entrants into the industry. Then by arguing that it is unethical to compete over price, they can increase the price without fearing a flood of new entrants.

Implicit agreement may succeed when it is easy to communicate the agreed price and to detect cheating. Thus, collusion is easier the fewer the number of firms in the industry and the more standardized the product.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 9. Non-Cooperative Oligopoly:

Collusion is difficult if there are many firms in the industry and the product is not standardized and if demand or cost conditions are changing fast. It would be more difficult when firms cannot discover the price charged by their competitors. Each firm, then, has an incentive to cheat its rivals.

In the absence of collusion, the firm’s decision is strategic. Its own demand curve depends on how competitors react. We have already seen that different guesses about competitors’ reactions would generate competitive solution (the Bertrand Model) and the collusion monopoly solution which will prevail when each firm believes that any price cut will be completely matched by other firms.

There is a complete spectrum of beliefs about competitors’ reactions, ranging from no price response to complete response. For each belief, the individual oligopolist will behave as if it faces a different demand curve and will make different price and output decisions. We now consider the kinked demand curve model, a leading example of intermediate class model.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 10. Kinked Oligopoly Demand Curve:

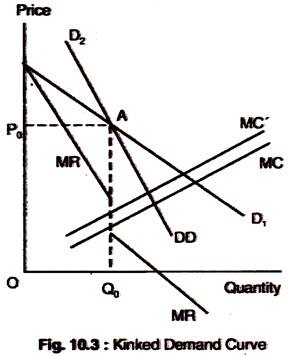

Suppose each firm believes that its own price cut will be matched by all other firms in the industry but that an increase in its own price will induce no price response from competitors.

Fig. 10.3 shows the demand curve, DD that each firm would then face. The price is P0 and the firm is producing Q0. Since competitors do not follow suit, a price increase will lead to a large loss of market share to other firms. The firm’s demand curve is elastic above A, at prices above the current price, P0.

Conversely, a price cut is matched by other firms and market shares are unchanged. Sales increase only because the industry, as a whole, moves down the market demand curve as price falls. The demand curve DD is much less elastic for price reductions from the initial price P0.

The important point to note is that the MR curve is discontinuous at the output Q0. Below Q0, the elastic part of the demand curve is relevant, but at the output Q0, the firm suddenly encounters the inelastic portion of its kinked demand curve and MR suddenly falls. Q0 is the profit-maximising output for the firm, given its belief about how competitors will respond.

An important implication of the model is that even if the MC curve of a single firm shifts up or down by a small amount, it will not change price, P0, or output, Q0.

In contrast, a monopolist facing a continuously downward-sloping MR curve would adjust quantity and price when the MC curve shifted. The kinked demand curve model may explain the empirical finding that firms do not always adjust prices when they face a change in costs.

The model does not explain what determines the initial price P0. One possible interpretation is that it is the collusive monopoly price. Each firm believes that an attempt to undercut its rival will provoke them to cooperate among themselves and retaliate in full. However, its rivals will be happy for it to charge a higher price and see its market share destroyed.

One advantage of interpreting P0 as the collusive monopoly price is that it contrasts the effect of a cost change for a single firm and a cost change for all firms. The latter will shift the MC curve up for the industry as a whole and increase the collusive monopoly price.

Each firm’s kinked demand curve will shift upwards since the monopoly price, P0, has increased. Thus, we can reconcile the stickiness of a single firm’s prices with entire industry mark up prices when all firms’ costs are increased by higher taxes or inflationary wage settlements in the whole industry.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 11. Monopolistic Competition:

The essence of oligopoly is the interdependence of firms. With significance economies of scale, there are only a few firms or a few potential entrants. Each firm’s demand curve is sensitive to how its rivals react. Since each firm must estimate the position of its own demand curve, it must think carefully about how it believes rival firms will behave.

In contrast, the theory of monopolistic competitors envisages a large number of small firms so that each firm can neglect the possibility that its own decisions provoke any adjustment in other firms’ behaviour. We also assume free entry and exit from the industry in the long-run.

In these respects, the framework resembles our earlier discussion of perfect competition. What distinguishes monopolistic competition is that each firm faces a downward-sloping demand curve because the products that firms make are differentiated.

Monopolistic competition describes an industry in which each firm can influence its market share by changing its price relative to its competitors. Its demand curve is downward- sloping because different firms’ products are not homogeneous.

Monopolistically competitive industries exhibit product differentiation. For the corner grocer, this differentiation is based on location, but in other cases it is based on brand loyalty. The special features of a restaurant or a hairdresser may allow that firm to charge a slightly different price from other producers in the industry without losing all its customers or completely taking over the entire market.

Brand loyalty and product differentiation may be important in many industries without being monopolistically competitive. Brand loyalty limits the substitution between Ford and British Leyland in the car industry but the key feature of the industry remains the oligopolistic interdependence of the decisions of different firms because there are so few producers in the industry.

Monopolistic competition requires not merely product differentiation, but also limited opportunities for economies of scale so that there are a great many producers who can neglect their interdependence on any particular rival. Hence, many of the best examples of monopolistic competition are service industries where economies of scale are small.

The industry demand curve is the horizontal sum of the demand curves of the individual firms in the industry. The market share of each firm depends on the number of firms and on the price it charges. For a given number of firms, a shift in the industry demand curve will shift the demand curve of each individual firm.

For a given industry demand curve, an increase (decrease) in the number of firms in the industry will shift the demand curve of each firm to the left (right) as its market share falls (rises).

For a given industry demand curve, number of firms, and price charged by all other firms, a particular firm can increase its market share to some extent by charging a lower price and inducing some consumers to switch over to its particular product.

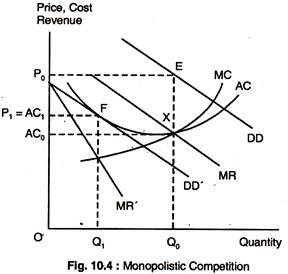

Fig. 10.4 illustrates the supply decision of a firm. Given its own demand curve, DD, and MR curve, the firm produces Q0 at a price PQ making short-run profits equal to Q0 x (P0 – AC0). In the long-run, these profits attract new entrants, who dilute the market share of each firm in the industry, shifting their demand curves to the left.

Entry stops when each firm’s demand curve has shifted so far to the left that P – AC, and firms are just breaking even which occurs when demand has shifted to DD’ and the firm produces Q1 at a price P1 to reach the tangency equilibrium at F.

In monopolistic competition, the long-run tangency equilibrium occurs where each firm’s demand curve is tangent to its ACC at the output level at which MC = MR. Each firm is maximising but just breaking even. There is no further entry or exit.

Two things are worth noting about the long-run equilibrium. First, the firm is not producing at minimum point on the ACC. It has excess capacity and, hence, it could reduce AC by expanding output but its MR would be too low to be profitable.

Second, the firm retains some monopoly power, as price exceeds MC, because of the special feature of its particular brand or location. This helps to explain why firms are eager to attract new customers at the existing price. But, under perfect competition, the firm does not care whether other customers are buying at the existing price with P = MC; the firm is already selling as much as it wants.

The theory of monopolistic competition provides interesting insights when there are many goods, each of which is a close but not a perfect substitute for the other. For example, it explains why Britain exports cars (Jaguars) to Europe and at the same time imports other variety of cars (Mercedes) from the Continent. In the absence of trade, the domestic car market would have room for only a few varieties.

Producing a large number of brands at low output would raise AC. International trade allows each country to specialise in a few types of car and produce a much larger output of that brand than the home market can support. By swapping these cars between countries, it is possible to give consumers a wider range of choice while allowing each individual producer to enjoy economies of scale and hold prices down.

Market Structure and Imperfect Competition # 12. Monopolistic Competition and Economic Efficiency:

Perfectly competitive markets are desirable because they are economically efficient and so long there are no externalities and nothing impedes the workings of the market, the total consumer’s and producer’s surplus is as large as possible.

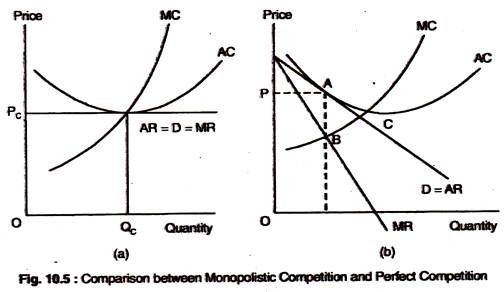

Monopolistic competition is similar to perfect competition in some respect, but is it an efficient market structure? Comparison between the long-run equilibrium of a monopolistically competitive industry and the long-run equilibrium of a perfectly competitive industry will be able to answer this question.

Under perfect competition, as in Fig. 10.5(a), price = MC, but under monopolistic competition P > MC, so, there is a deadweight loss (of surplus) as shown by the area ABC in Fig. 10.5(b). In both types of markets, entry occurs until profits are driven to zero. Under perfect competition, the demand curve facing the firm is horizontal, so the zero-profit point occurs at the point of minimum AC.

Under monopolistic competition, the demand curve is downward- sloping, so the zero-profit point is to the left of the minimum point of AC. In evaluating monopolistic competition, these inefficiencies must be balanced against the gains to consumers from product diversity and to the society of very small excess capacity.