In this article we will discuss about the history of prices in India during different periods.

Gradual rise in Prices, 1861-1904:

Before the advent of the railways, prices were extremely low in India. At the beginning of the 17th Century, the price of wheat in Punjab was 90 seers per rupee. In Sikh times, wheat was selling at the rate of one rupee a maund in large cities and even then, it was considered dear than cheap.

Prices in other parts of the country were equally low. In Farrukhabad, for instance, wheat sold at the rate of 47 seers to a rupee in 1803, 48 seers in 1835 as well as in 1848 and 31 seers in 1859.

From 1861, however, prices began to more upwards and throughout the period, 1861-1904, they showed a tendency towards a slow and gradual rise. Between 1861-1904, there was an overall increase of 12% in the general Price level, the index having moved from 90 in 1861 to 101 in 1904 (1873 = 100). It may, however, be noted that the rise in prices was not regular and continuous.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In-fact, prices fluctuated from year to year although these fluctuations were not as great and violent as before. With the construction of railways, prices did not fall heavily when the harvests were good and they did not rise sharply when they were poor or scanty.

An important feature of the price level was its complete domination by prices of food. Food prices generally ruled high and those of raw-materials and manufactured articles remained relatively low.

This may be seen from the fact that between 1861-1896 while food prices rose by 48%, those of raw-materials increased by 39% and of manufactures by 12%. This is, of course, what would be expected in a poor country where a large portion of the disposable income was always spent on food.

Causes:

Three factors were mainly responsible for the rise in prices during this period:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The first was the rise in the prices of food grains brought about by their growing exports — especially of wheat. Prior to the construction of railways in India, there was little export trade in food grains. By 1876-80, the railway net work had covered the principal parts of the country. As a result, annual exports of wheat reached an extraordinarily high level of one million tons in 1881-1882.

It was this expansion of wheat exports, as the Dutta Committee pointed out, which “exercised a very important influence on the price of Indian wheat.”

This may be seen from the fact that in 1891, the wheat crop in India was exceptionally good, but to meet a strong demand from Europe, more than 18% of this produce was exported and prices in India rose. In 1892, however, in-spite of a poor harvest, prices did not rise on account of a decline in European demand.

Secondly, the extension of cultivation after 1860 led to an increase in the demand for labour, plough-cattle, and agricultural implements and their prices consequently rose. For example, the price of a plough-bullock in Kot-Khai (Shimla District) was rupees 5 in 1849 and rupees ten in 1883. In Jhelum (Punjab), the price of a bullock in 1858 was rupees 40/- but rose to rupees 55/- in 1877.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Likewise, the Settlement Report of Karnal (Haryana) 1872-80 records that the price of water from irrigation, since 1842, had risen by 150%. The Report on the Second Regular Settlement of the Gujarat District (now in Pakistan) records a rise in the price of agricultural implements from Rs. 72.63 in Sikh times to Rs. 97.53 in 1874. What was true of the Punjab was broadly true of the country as a whole.

Thus, expanding wheat exports on the one hand and rising cost of cultivation on the other combined to push up agricultural prices. Other prices followed.

Another factor was “the large influx of Silver into the country which allowed the currency to expand in a greater measure.” In the Revised Settlement Report of the Shahpur District, (now in Pakistan) “the larger influx of Silver from Europe” is mentioned as one of the causes of the rise in prices. This import of Silver was a cause operating throughout India especially during 1861-70 and again between 1886-1890.

A momentous event during 1861-70 was the American Civil War which, while it lasted, brought large profits to the cotton cultivator and merchant. The resultant influx of precious metals caused a great rise in prices. The period 1886-90 is still more remarkable.

There was neither any major famine nor a larger export of wheat in this period which could explain the rise in the price index from 87 in 1885 to 101 in 1889. This was mainly brought about by “the heavy imports of silver” and the increase in active circulation of money brought about by ‘the large additions to the coinage.’

To conclude. The rise in prices during 1861-1905 was slow and gradual and was largely brought about by expanding wheat exports, increase in the cost of cultivation and expansion of currency.

Rapid Rise in Prices, 1905-1914:

The year 1905 marks a new chapter in the history of Indian prices. Before 1905, while famine or scarcity raised the prices of food grains, favourable monsoons lowered them. The rise in prices thus lasted for a short time. From 1905, a change came about in so for as the rise in prices was almost continuous as well as spectacular. The price index moved from 110 in 1905 to 147 in 1914 (1873 = 100)——- a 34% rise.

The rise was not confined to any particular region or a particular commodity, but covered all parts of the country and all principal commodities, although the prices of exports rose much more than the prices of goods sold in the home market.

What was more disturbing was that the rise of prices in India was greater than in other countries. The Dutta Committee, for instance, found that the level of prices during the 5 —yearly period, 1907-1911, when compared with the 5 —yearly period, 1894-98, showed an increase of 40% in India but only 21% in the U.K., 38% in the U.S.A., 26% in France and 20% in Australia.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The rise in Indian prices attracted much attention and caused great uneasiness. Attention was first drawn to it by an anonymous writer who concluded that “the floods of rupees entering the country in the busy season must, finding no employment thereafter, choke the circulation in the dull season and raise prices while each succeeding year, the demand grows like a snow ball down a slope.”

Critics of the British rule in India asserted that the exceptional rise in Indian prices was a symptom of a deep-rooted disease in the economic system of the country. Some held that the increase in the price level was due to scarcity of supply created by an ever-expanding exports of food stuffs while others like Gokhale attributed it to the heavy coinage of rupees by the Government.

In view of this criticism, the Government of India appointed in 1910, a committee for the investigation of the problem. The Dutta Committee recognised that “up to 1905, fluctuations in the prices of food grains and pulses depended largely on the agricultural conditions” but thereafter the existence of ‘famine prices without famine’ was brought about by (a) certain world factors and (b) certain causes peculiar to India.

Among the general causes which raised prices throughout the world were:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(1) A shortage in the supply of, or an increase in the demand for staple commodities in the world’s markets;

(2) Increased gold supply from the World’s mines;

(3) Development and expansion of credit;

(4) The growth of armaments in most of the western countries including U.S.A. which caused the demand for many types of commodities to rise.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(5) In addition, the committee also mentioned emigration from old to new countries, the sinking of capital in new countries and the growth of trusts which restricted production as factors contributing to the rise in world prices. India shared these fluctuations in world prices as she, having abandoned the silver standard in 1893, had switched on to the currency gauge of the world.

Causes Peculiar to India:

The committee dismissed the argument of the nationalists led by Gokhale that the expansion of currency was the main cause of the price rise in India. According to the committee, as compared with the average of 1890-1894, while business had expended by 112% up to 1911, the circulation of rupees increased by only 64% up to 1912.

In its view, therefore, the growth of the volume of currency including notes had “not been incommensurate with the growth of business and other demands for currency and, in the absence of any indications of a redundancy of rupees for any length of time, it is clear that the rupee coinage of the Government of India could not have exercised any important influence on the level of prices.”

According to the Dutta Committee, the World factors apart, there were four main causes peculiar to India which brought about the rise in prices.

These were:

1. Disparate Growth of Cultivation and Population:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Mr. Dutta, one of the principal causes which led to the rise of prices in India was a shortage of supply, particularly in the case of food grains.

By shortage of supply was meant not that the total production of the country had actually contracted as compared with the basic period (1890-94) but that production had “not kept pace with the growth of internal consumption and external demand” on account of such factors as unseasonable rainfall, substitution of non-food for food crops, inferiority of new lands taken up for cultivation, and the growth of cultivation not keeping pace with the growth of population and food exports.

2. Increased Demand for Commodities in India:

The general rise in prices was also due in part to the increased demand for all kinds of commodities which, in turn, was brought about by the rise in the standard of living amongst all classes of the population.

3. Expansion of Communications:

Another of the most important causes which raised the general price-level in India was “the lowering of the indirect and direct cost of transport in India itself and between the Indian ports and foreign countries.” Taking 1890-94 as the base, between 1896-1912, there was 38% reduction in the railway freight on tea, 40% on coal, 27% on jute and 20% on cotton, grain and pulses.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A similar reduction took place in the maritime freight between India and other countries. Taking the four ports of Bombay, Calcutta, Karachi and Madras together, freights in 1905-09 were 17% lower than in 1890-93. This led to an expansion of traffic both in India and abroad. The prices in the Indian sea port towns were already linked with world prices and the reduction in sea freights made that link more intimate.

Therefore, as world prices rose, prices in the Indian port towns also moved up in sympathy. The lowering of the cost of transport within the country tended to move inland prices closer to those prevailing in the sea-port towns and central markets.

4. Improvement in the General Monetary and Banking Facilities:

Another factor responsible for the price rise in India was the expansion of banking and credit facilities. According to the Committee, as compared with the average of 1890-94, the capital of banks in India in 1911 had increased by 115%, deposits by 232%, and clearing house returns by 210%.

Consequently, greater volume of credit was available to business which increased by 112% only. The conclusion was, therefore, drawn that “credit also contributed to a certain extent” to the rise in prices in India.

Examination of the Report:

The Government did not accept Mr. Dutta’s view that a relative shortage of supply was the main cause of the rise in prices before the war. It held that the commercial crops occupied a very small proportion of the total area under cultivation, and that in the country as a whole, there was no substitution of non food for food crops.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Besides, during the period 1905-12, the growth of population was not much more rapid than the growth of food-supply. Mr. Dutta’s estimate of food production were also not regarded as reliable.

The Government, however, seemed to attach more importance to world factors than to causes peculiar to India. Such a view can be objected to on the ground that if Indian prices rose under the influence of world factors, they could not have risen to a greater extent than the world prices.

The expansion of communications and the lowering of the cost of transportation in India and the foreign countries also could not be the cause.

The increase in transport facilities the lowering of sea freights undoubtedly linked Indian prices to world prices more closely. That is why Indian prices began to rise in sympathy with the world prices. But the expansion of communications does not explain why prices in India rose to a greater extent than prices in other countries.

Similarly, expansion of banking and credit facilities can’t explain the great increase in prices in India where, banks were then few, and where cash and not credit was used in great majority of transactions. The Indian cultivator had and still retains to an extent, a marked preference for coins.

It is true that the amount of cheques used in commercial transactions increased but the increase was not sufficient enough to exercise a decisive influence on the course of prices.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We have to consider, last of all, whether the rise of prices was, in any measure, due to the inflation of currency. One of the arguments used by Mr. Dutta in support of his view that the rise of prices was not due to the excessive issue of currency was that, from 1898 to 1912, the exchange value of the rupee in terms of gold never fell below 1s. 4d. except in 1908-09.

In this connection, it needs hardly be emphasised that under a Gold Exchange system where the rate of exchange is controlled by the Government, the stability of exchange is no argument against the excessive issue of currency, nor is a temporary fall in exchange a necessary consequence of inflation.

In fact, there is very little relationship between the volume of a taken currency and a ‘managed’ exchange. Mr. Dutta’s finding that the quantity of money increased much less than the increase in business activity and his conclusion that the increase in the quantity in circulation had no important effect upon the price level are open to serious objections.

Mr. Dutta’s estimate of rupee circulation, in the first place, did not include the circulation of sovereigns which formed part of our currency before the war.

Secondly, it did not include the circulation of small silver coins.

Thirdly, while Mr. Dutta found no change in the velocity of circulation of currency and credit, in reality, the increase in rapidity was remarkable enough to attract Dr. Marshall’s attention who made a reference to it in his evidence before the Fowler Committee. Lastly, it is also doubtful if the committee’s general index of the growth of business was also reliable.

In reality, the question of the rise in the prices was intimately connected with the nature of our currency system. A Gold Exchange Standard does not work automatically as held by the committee and it is precisely for this reason that the currency became redundant during the years 1905-12 and prices rose.

When the rupee was a full-value coin, it was freely exported as bullion; it was melted down to make ornaments and it was also hoarded. According to Mr. Atkinson’s estimate, hoarding and melting together accounted for about 45% of the coinage during 1862-92 and it was this which prevented the rapid rise in prices during that period.

However, after 1893, when the rupee became a token coin, the melting of rupees ceased altogether, while for purposes of hoarding, gold was preferred. And since India’s balance of payments was mostly favourable, they were not exported either. On the other hand, their supply constantly increased.

Mr. Dutta really proves nothing when he says that “the average annual coinage during 1893-94 to 1911-1912 was much less than in the period 1874-75 to 1893-94.” It is true that rupee coinage had declined but it was more than made up by large increase in silver coinage. Total money supply in the country, therefore, increased.

This change in the character of the rupee from a full value to a token coin, by discouraging hoarding and making it unprofitable to melt rupees, created an excess of currency as well as inflation in the country.

Inflationary Rise of Prices, 1914-20:

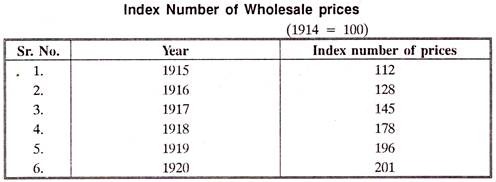

Even before the war, prices had been rising at a rapid pace. During the war, prices rose to unprecedented heights. The index of wholesale prices (1914 = 100) rose to 201 in 1920, thus marking a 100% increase in the price level.

The rise in prices was shared by all commodities including necessities of life. For instance, food grain prices rose by 93%; Imported piece goods by 187.5%; Indian piece-goods by 61.5%.

A peculiar feature of the war-time inflation was that the prices of imported articles rose much more than those of articles exported from India. This is evident from the fact that the index number for exported articles rose to 195 in 1920 and that for imported articles rose to 266 (1913 = 100). Among the exported articles, the rise of prices was greatest in the case of sugar, cotton manufactures, skins, coal, lac and indigo.

Prices in most countries were highest in 1920 as in India but the extent of the price-rise was greater in other countries than in India. This may be seen from the fact that the price-rise between 1913-20, was 159% in Japan, 207% in U.K., 409% in France, 126% in U.S.A. whereas in India, it amounted to just 100% between 1914-1920.

This peculiar phenomenon of a relatively smaller price-rise in India attracted the attention of many writers. Mitchell put forth the view that the slower movement of Indian prices was due to the influence of customs and defects in her commercial organization. A more superficial explanation could not have been offered.

Indian Commercial organisation might have been less advanced than the American or European. It is also true that there is much economic friction in India even today. But that, however, did not prevent Indian prices from rising more rapidly than European prices before the war.

In reality, as Jackson’ explains, the general rise of prices in almost all countries was due to inflation. Prices rose to a greater extent in countries more directly involved in the war on account of the greater amount of currency expansion in those countries.

The slower movement of Indian prices was, therefore, due neither to the influence of customs nor defects in commercial organisation but to the fact that the causes which raised prices in Europe and America were working in India in a much less severe form. Also, the restrictions imposed on exports by the shortage of shipping and by Government control checked, to some extent, the price rise in India.

This disparity between Indian and foreign prices would have been corrected had the Government allowed free play to market forces. The lower level of prices in India would have encouraged exports, discouraged imports, thereby leading to a flow of precious metals into India. This would have increased the currency in circulation and caused internal prices to rise to the level of foreign prices.

However, the import of precious metals into India was strictly restricted, and, at the same time, exports were artificially limited by Government control. This meant that the tendency towards equilibrium by increased exports at enhanced prices was artificially stopped, and Indian prices failed to achieve equilibrium with world prices.

The rise in prices in India, though less as compared with other countries, was great enough to promote “unrest and discontent.” Generally speaking, there was no shortage in the supply of food stuffs and raw-materials except in 1918 and 1920 when rains failed.

The rise in the prices of manufactured goods was, in a large measure, due to shortage caused by the stoppage of trade with enemy countries and the heavy decline in imports from Allied and neutral countries.

This may be seen from the fact that the imports of boots and shoes declined from 3.2 million in 1913-14 to 0.63 million in 1918-19; of cotton piece-goods from 3.1 million yards to 1.1 million yards; of sugar from 1.2 million tons to 0.5 million tons and of woolen piece goods from 27,000 yards to 6000 yards.

The shortage was further aggravated by the scarcity of rolling stock which could not ensure a more equitable distribution of available supplies in the country. However, the major cause of the war-time rise in prices was the inflation of currency. The balance of trade, after the out-break of the war, remained strongly in India’s favour.

At the same time, there was a serious reduction in the imports of precious metals, thus throwing upon the Government the whole responsibility for financing the export trade by issuing a large volume of additional currency in the form of Rupees as well as currency notes. There were also large disbursements in India on behalf of the war office in London.

In 1918-19 alone, the total disbursements in India, for which it was necessary to provide, amounted to £ 141 million —more than half of this sum representing war outlay on behalf of the British Government. There was thus an enormous expansion of currency of all kinds; between 1914-19, active note-circulation increased by 168% while business expanded by a bare 15%.

The process of inflation was also helped by the methods adopted by the Government to finance the war. In order to meet the heavy expenditure, the Government relied partly on increased taxation and loans and partly on artificial creation of purchasing power. The war loans of the Government also inevitably led to inflation because only a portion of these loans came out of the real savings of the people.

The remainder took the form of bank credits or the creation of deposits. The short-term Treasury Bills which were issued by the Government of India for meeting successive budget-deficits were another source of inflation as banks lent freely against their security and that of the war bonds.

There was thus a very large increase in the Bank deposits (credit) as well as their velocity which supplied so much more buying power and thereby contributed to the rise of prices.

The war hit India very hard. Shipping difficulties as well as the enormous disparity existing between Indian and world prices denied the Indian exporters the advantage of increased exports at higher prices while it made importers pay relatively high prices.

Indian producers were thus placed at a disadvantage in so far as they were prevented from building up reserves that could be drawn upon during the subsequent depression.

The Deflationary Fall in Prices, 1920-29:

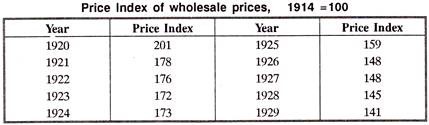

Since the end of the war, on account of the operation of abnormal factors, the Indian price level was moving up. It reached its peak in 1920 when the wholesale price index reached 201 (1914 = 100). Thereafter, it continuously declined the price index reading 141 in 1929.

Though the trend of Indian prices was in line with that in other countries, the fall in Indian prices was much less. While in India, the price index fell by 60 points between 1920-29, the fall in the U.K. was by 155 points, in U.S.A. by 129 points and in Japan by 88 points during the same period.

It may also be noted that after the precipitate decline in prices in 1921, the fall up to 1923 was gradual while that between 1924-26 was more steep.

It may, however, be pointed out that, throughout the period 1920-29, the fall was much greater and more continuous for food stuffs than for industrial materials. The Index number of wholesale prices of cereals declined from 153 to 125, of Sugar from 407 to 162 while that of oil-seeds fell from 173 to 155 in the period 1920-29.

This was on account of such world factors as the war-time expansion of production due to the extension of acreage and technological progress in agriculture, especially in countries such as the U.S.A. and the British Dominions. Also, harvests were good from 1921-24.

The major cause of the fall in Indian Prices lies in Government attempts to hold a particular rate of exchange between the rupee and the sterling. In order to understand it properly, one has to go back to the ‘disastrous deflation’ deliberately undertaken by America in 1920.

This caused a similar deflation in other countries which were anxious to prevent the depreciation of their currencies in terms of dollar. In this way, a general process of deflationary contraction was initiated in March 1920, after the short-lived post war boom, leading to a fall in prices all over the world.

In India, following the recommendations of the Babington Smith Committee, the authorities had blundered into over-valuing the rupee at 2s. Gold —a rate rendered untenable by the unexpected turn of circumstances. The Sterling — Dollar Cross-rate declined thereby raising the Rupee —Sterling rate of 2s Gold to 2s. 10¼d. on 11 February, 1920.

This extraordinary rate greatly encouraged the remittance of funds, partly genuine and partly speculative, to England. At the same time, the balance of trade became un-favourable; exports fell from Rs. 330 crores in 1919-20 to Rs. 258 crores in 1920-21 while imports, encouraged by the new rate of exchange, rose from Rs. 208 crores to Rs. 336 crores during this period.

In view of this sea-change in the economic situation, the Rupee-Sterling rate began to fall. In its efforts to maintain the new ‘norm’ of 2s gold, the Government took to official administration of currency. On the one side, equilibrium was restored in the budget by economy, retrenchment, and an increase of taxation. On the other hand, currency was contracted between the years 1920-21 to 1922-23 to the tune of Rs. 38.5 crores.

This explains why Indian prices declined from 201 in 1920 to 172 in 1923. That the decline was less as compared with other countries was due to the reason that the Government did not find it possible to deflate Indian currency to the extent necessary because of a succession of deficit budgets which obliged the Government to borrow from the Currency Department against Treasury Bills.

It is not out of place to mention that one result of this fall in prices was that industrial development which had started during the war and was well under way during the post-war boom, received a set back. What was worse, even the exchange rate of 2s gold also could not be maintained and ultimately the exchange was left free to find its own level.

Once the rupee reached 1s. 4d. in October, 1924, all efforts of the Government were directed towards preventing its rise above that rate. In pursuance of this policy, either the currency was not duly expanded or it was contracted. For example, from June 1924, both the U.S. and the U.K. index began to move up wards.

The Government, with a view to preventing any sharp upward movement of the exchange, expanded currency between October, 1924 to March, 1925 to tune of Rs. 14 crores —8 crores against internal Bills of Exchange and Rs. 6 crores against British Treasury Bills and even raised the minimum limit of fiduciary Issue from Rs. 85 crores to Rs. 100 crores by amending the Indian paper currency Act in 1925.

But this limited expansion proved inadequate for the very large volume of trade and business. Indian prices, therefore, declined from 173 in 1924 to 159 in 1925.

During 1926-29, the exchange rate continued to be weak and the Government supported it by contracting currency in many ways —sometimes by transferring sterling securities from the paper currency Reserve in England to the Secretary of State and making a corresponding withdrawal of notes in India and sometimes by cancelling the adhoc securities in the paper currency Reserve in India leading to a corresponding contraction of note-issue.

Prof. Brij Narain has estimated that between 1920-21 to 1929-30, there was a net withdrawal of currency amounting to Rs. 86 crores.

Thus, it is evident that while a certain part of the fall in Indian prices was in sympathy with world prices, a greater part was caused by the monetary policy of the Government which sought to achieve exchange stability and deliberately brought about internal price fluctuations.

From 1926-29, prices in India were relatively stable and it appeared that they had settled down. The condition, however, did not last long. From 1929 commenced the Great Depression the like of which had never been witnessed before and from which no part of the civilized world escaped.

The Great Depression and After, 1929-39:

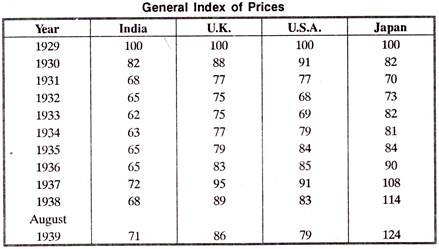

The downward movement of prices was greatly accelerated during the period of the world Depression which was ushered in by the Wall Street collapse in America in October, 1929. Prices began to decline rapidly and reached their lowest level in 1933 when the wholesale index (1929 = 100) reached 62.

There was some recovery in the next two years but it was in the later part of 1936 that prices began to rise and the rise was continuous till August, 1937. After that, prices began to fall and were generally on the decline till the end of June, 1938 when they showed an insignificant rise which was more or less maintained till the end of 1938.

A serious aspect of the fall in prices in India, in common with the rest of the world, was that it was not uniform. The fall of prices was much greater and sudden in the case of food-stuffs and raw-materials than in the case of manufactured goods.

The price of jute and cotton manufactures, for instance, declined by 44% and 30% respectively between September, 1929, to March 1933, while the prices of raw-jute and raw-cotton fell by 58% and 46% respectively.

The other disparity was between the price of cereals and raw-materials. The price of industrial raw- materials fell the most the largest decline of 63% being in the case of oil-seeds followed by raw-jute, hides and skins, and raw-cotton.

The fall in the price of cereals, excepting rice whose price fell by 58%, was comparatively less, being only 34% in the case of wheat. This greater fall in agricultural raw-material prices meant a deterioration in the terms of trade between India and other industrial countries like the U.K.

A study of the movement of individual commodity prices shows that they were not influenced by any common factor. Instead, different factors were at work in determining the prices of different commodities. Raw jute, for instance, was one of the worst Victims of the depression. Its bad days started in 1927. The depression merely recorded the ‘nemesis’.

The unprecedented fall in its price was due to over-production, better bargaining position of jute mills, large stocks, and the prevalence of a purely gambling spirit in the jute market. The fall in the price of wheat was brought about by Shrinkage of the world market and competition among exporters.

As regards oil-seeds, west-African competition and cheap supply from Argentina almost ruined out foreign market. The decline in the price of rise was caused by competition from Siam and Indochina, stoppage of exports to china and Japan, and the loss of the Philippines market. Price of raw cotton remained low mainly because of the boycott of Indian cotton by Japan and the bumper cotton crop in the U.S. in 1930-31.

Although prices in India followed a course, more or less, parallel to that in the U.K. and U.S.A., yet the extent of the fall of prices in India was greater, and what is more, of a longer duration. For example, the % age decline from the peak in 1929 to the lowest level reached was 44.3 in India as compared with 30.4% in the U.K., 38% in the U.S.A., 28.5% in Australia and 35.8% in Japan.

Likewise, the fall in prices was checked in other countries much earlier. Japan checked the fall in 1931, U.K. in 1932, and Germany in 1933. India, however, remained an exception where the decline in prices continued till 1933. Even thereafter, the process of recovery was very slow; the general price index did not go very much higher than where it had been checked till the start of 1937.

This is evident from the fact that between 1933—1937, while the Indian index rose from 62 to 73, gain of 11 points only, the price index in U.K. gained 20 points and that in Japan, 27 points.

The reasons for the steeper fall of prices in India as well as for the persistence of the depression for a longer duration were many. The first was the nature of the Indian economy. It is comparatively easier to restrict output of industrial goods and adjust their supply to demand.

The supply of agricultural commodities, being relatively inelastic, naturally takes longer to adjust itself to demand. It is therefore, that agricultural countries including India suffered the most.

Other agricultural countries like Australia, New-Zealand, Brazil, Denmark and Argentina, however, counteracted it by a drastic reduction of imports am by a depreciation of exchange. By the beginning of 1933, countries representing 52% of the world trade had depreciated their currencies.

India also could have profitably followed this course but the Government pinned her faith in the traditional policy of exchange stability despite the devastating shocks of the depression which it transmitted to the Indian economy.

Besides, there was no positive action, comparable to the New-Deal, on the part of the Government of India to bring about recovery. State intervention and fiscal policy became an essential part of the measures adopted in other countries to fight the depression.

Even in Laissez-Faire countries, the State took upon itself the responsibility of establishing remunerative prices through price-support measures and increased the purchasing power of the masses through deficit-budgeting and public works programme. But, in India, no such expansionist policy was followed; rather the Government was more worried about maintaining a balanced budget.

The major share of the blame must, however, lie on the monetary policy of the Government. Ever since the 1s. 6d. gold ratio was fixed in 1927, the Government “expressed, reiterated, affirmed and reaffirmed their determination to maintain it”, although economic conditions prevailing in India from 1927-31 furnish no evidence that this contributed to stability and progress.

On the other hand, when the downward trend of prices and trade began, the 1s. 6d. gold rate accentuated the fall. The reason was that this rate, having greatly overvalued the rupee, had to be supported by large contractions of currency which took place between 1926-27 to 1930-31. Net contraction of currency notes during this period was no less than Rs. 102.5 crores.

The abandonment of the Gold Standard by England and the Linking of the rupee to Sterling and the consequent conversion of 1s. 6.d. Gold to Is. 6d. sterling was a ‘disguised depreciation’ of the rupee in relation to gold.

This immediately raised Indian prices and stimulated exports to countries having currencies based on gold. But even at 1s. 6d. sterling rate, the rupee was over-valued and its strength and stability was mainly derived from ‘Gold Exports’ which took place in this period.

When gold exports declined in volume and balance of trade, after June 1938, began to turn more and more unfavorable, the exchange began to show signs of weakness and had once again to be supported by further contraction of currency and credit.

Thus it is clear that first, it was the 1s. 6d. gold rate and later the 1s. 6d. sterling rate which the Government was determined to maintain irrespective of its consequences to internal price stability. Faced with a similar situation, England, Sweden, Egypt, Japan, U.S., Belgium, France, Australia, Holland, Italy, depreciated or devalued their currencies and succeeded in stabilising internal prices by reflationary adjustment.

However, the Government of India, with rare grit and determination, stuck to 1s. 6d. ratio, the deflationary effects of which in the words of Prof. D.K. Malhotra, “spread out like a heavy blanket over the Indian Economy- obstructing recovery and expansion.”

Prices during the Second World War, 1939-45:

Among the various war-time developments in the Indian economy, the enormous rise in the price level and the cost of living overshadowed all others by its “spectacular character, its wide sweep, and its direct impact on the daily life of the Common man” leaving aside Greece and China, where runaway inflation prevailed, India was among the countries, which experienced the highest increase in price level.

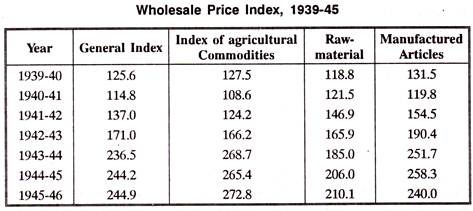

In August, 1945, which witnessed the surrender of Japan and the return of peace, the wholesale price index (19 August, 1939 = 100) stood at 224.

A point worth noting is that the rise in the price level was not uniformly spread over the period of the war, there being considerable variations in the rate of increase from year to year. Immediately on the out-break of the war, commodity prices in India took an upward turn mainly as a result of speculation.

In Madras, the price of rice went up by 10-20%, the wholesale price of sugar rose by 30%, castor, cocoa-nuts and copra by 40-50% and Coconut oil by 64%. Fortunately, this rise proved short-lived and spent itself out by June 1940.

In the second half of 1940, however, an upward trend in prices was again set in motion which continued till the middle of 1943. This period is important in so far as it witnessed the maximum price increase, the price index rising from 137 in 1941-42 to 236.5 in 1943-44. The period from the middle of 1943 to the end of the war in 1945 was characterised by a great measure of stability although it was maintained at a high level.

It is also interesting to note that, up-till the middle of 1943, prices of agricultural commodities lagged behind those of manufactured articles. But from July 1943, they not only overtook them but even stole a march over them.

During 1943-44, as a result of the adhoc control orders, the Hoarding and Profiteering Ordinance, release of large stocks for civilian consumption and increased import of essential commodities, the prices of manufactured articles declined after reaching their peak in 1944-45.

On the other hand, the prices of food grains and raw- materials, under the stress of scarcity and cutting-off of rice supplies from Burma, registered a sharp increase from 1943-44. The disparity in the prices of agricultural and industrial articles, thus, tended to be restored by price changes during the war.

Although, the rise in prices was common all over the world, yet there was considerable variation in the degree and timing of the price rise, as d. Bright Singh points out, in the U.S.A., the U.K. and Canada, which had an efficient administration and a high degree of economic development, wholesale prices, between 1939-45, rose by 38%, 64% and 39% while the cost of living went up by 28%, 29% and 19% respectively.

In India, on the other hand, the general price level went up by 93% and cost of living by 117%. Similarly, in other countries, the greater part of the increase took place before the end of 1941. Since the beginning of 1942, the price rise was slow and gradual. In India, the major increase, as already noted, took place after 1941.

Amazingly, the attitude of the Government was first to deny the existence of inflation in the country. As late as July 1942, the Reserve Bank held the view that although most of the recognised elements of inflation were present, there was no evidence that inflation was present in the country in any serious form.

An indirect support to the official view was lent by Mr. G.D. Birla, a leading industrialist, who, in his pamphlet “Inflation or Scarcity”, categorically denied the existence of inflation in India and argued that the rise in prices was due to a scarcity of goods rather than the expansion of currency since the latter was more than offset by reduction in the velocity of circulation.

Professional economists, on the other hand, held the view that the inflationary spiral was already at work and that inflation was deficit-financed fiat-money inflation caused by the peculiar system of war-finance adopted in India. Let us analyse the various factors which brought about the rise in prices so as to understand the nature of the controversy.

Causes:

The main cause was the increase in Government’s military expenditure, both on its own behalf as well as on behalf of its Allies. According to Lokanathan, the total defence expenditure of India during the war amounted to about Rs. 2500 crores, giving an annual average which was three times India’s annual revenue at that time.

How was this vast expenditure met? For the expenditure incurred by India on their behalf, the British and Allied Governments made payments to the Government of India in sterling in London and the Government of India released the equivalent amount of rupees in India. Under this arrangement, sterling accumulated in London, was invested in sterling securities which formed the backing behind the notes issued in India.

In this way, while the total note circulation increased in India from Rs. 203 crores in September, 1939 to Rs. 1085 crores in March, 1945, the amount of sterling securities rose from Rs. 59.5 crores to Rs. 1029.3 crores. As L.C. Jain observes, the law was thus “observed in form but not in spirit”.

In normal times, any accumulated sterling in England could have been utilised for importing goods and services in India, but this was not possible during the war. In effect, therefore, India extended to Great Britain a huge commodity credit which was to be repaid after the war.

On the other hand, investment of sterling balances in British securities made available large funds to the British Government, who were, thus, able to avoid making use of credit inflation. In this manner, inflation was kept at bay in England but unleashed in India.

The backing of sterling assets behind expanded currency strengthened public confidence in it and, to that extent, it checked inflation. However, as these assets were incapable of being converted into goods, the increase of purchasing power in the country, resulting from note issue, was clearly inflationary in character.

In addition, scheduled banks’ demand deposits recorded an increase of 362%-from Rs. 133.5 crores in August, 1939 to Rs. 596.7 crores March, 1945. Also, rupee and small coins to the tune of Rs. 198 crores were absorbed during the war. Although and velocity of circulation declined but it was more than compensated by the huge expansion in the money supply.

On the other side, there were “omnipresent and cumulative” shortages in the country. In 1941-42, there was a failure of monsoons followed by natural calamities like cyclones. This led to a large decline in food production. At the same time, the enemy occupation of Burma stopped an important source of supply of food grains.

Apart from these, economic activities in the country fell far short of the needs of the country and the opportunities offered by the war. This may be seen from the index of agricultural production which moved to only 100.2 in I944-45 (average of 1934-35 to 1938-39 = 100) while the index of industrial production moved to 190.1 in 1945 (1937 = 100).

Agricultural production could not be increased in the short period due to the small and scattered nature of the holdings although there was a slight shift, in later years, from the production of raw-materials and non-food crops to food crops like wheat and rice.

Industrial production could not be raised firstly, because capital goods were required for war production and secondly, imports from outside were difficult owing to lack of shipping space and other reasons.

Mr. D.K. Malhotra estimates that during the war, there took place not more than 20-25% increase in India’s overall production. This increase was far too meagre in relation to the enormous expansion of purchasing power in the hands of the public. Prices consequently rose to undermine the already low standard of living.

Before the War, the total available supply of cereals was more than 45 million tons. During the first half of the war, it declined to 43 million tons. This when viewed against an increase of population of 4-4.5 million a year, indicates the nature and degree of shortage that it gave rise to.

By the middle of 1943, food became so scarce as to be almost unobtainable for the vast majority of population. No wonder, deaths occurred in the streets of Calcutta.

In the early years of the war, India’s main contribution was in the form of larger exports to its allies. Despite the licensing system, exports were not thoroughly controlled until 1942-43 when it was realised that the exports of grains and cotton piece goods were causing a serious drain on internal civilian supplies.

The export of consumer goods led to the growth of inflation at a time when the release of more such goods in the home market would have absorbed extra purchasing power.

Imports, on the other hand were reduced to a very low level. The commodities which suffered the most were food, drink, tobacco and manufactured goods. No doubt, India earned a large positive trade balance, but the supply position became so difficult that India “sought relief from its war-supply responsibilities in respect of non-munitions as well as munitions.”

The rise in prices was also accentuated by difficulties of transport and distribution and artificial shortages induced by speculation and hoarding. Speculative cornering became quite common in the markets for food items such as wheat, rice, and tea. It gathered strength with the increasing strain of military orders for goods on the nation’s economy and manifested itself in every channel of trade.

Inflationary-gap-the difference between total demand and total supply, characterizes most war economies, but this inflationary potential can be suppressed by means of a well-designed policy of direct controls.

In India, however, controls came very late; had very limited scope for application, and above all, were administered very imperfectly. This failure to suppress the inflationary potential was thus another potent cause of war-time inflation in India.

Viewed from this distance, the whole controversy regarding the cause of the rise in prices —scarcity of goods or monetary expansion was artificial and unnecessary. The controversy arose from the fact that the problem was viewed from two different angles which disclosed opposite facts of what was really the same phenomenon.

Scarcity of goods and currency expansion were the expression and the result of the considerable diversion of real resources from civilian to military use brought about by the issue of purchasing power created for this purpose and they together contributed to the rise of prices.

Government’s Policy:

Timely and effective measures to deal with the problem of inflation might have been undertaken had there been a clear understanding of the nature and gravity of the problem. Even as the war was half-way through, the authorities found no evidence of the presence of inflation “in any serious form”.

Furthermore, there was reluctance to recognise the sequence of cause and effect. It is, therefore, not surprising that the Government met the situation only through a series of sporadic steps.

The Government could and should have reduced its expenditure to a level where it could be covered by non-inflationary methods. This, however, meant a contraction of India’s war effort and obviously did not appeal to the authorities. Prof. C.N. Vakil urged the Government to refuse rupee finance at-least to Allies other than England.

Such a course would have compelled these countries to find the rupee finance themselves either by selling gold or through exports or by raising loans in India. This was also unacceptable to the Government.

Had India broken the rupee-Sterling link, the responsibility of finding rupee finance would have automatically shifted on to the shoulders of the Allies. But the link represented India’s slavery; it was a symbol of the relations between India and England and it could not be touched.

Since this was found impossible, the Government should have met its expenditure through non-inflationary methods of taxation, compulsory and voluntary loans and liquidation of foreign investments in India. This would have also ensured a more equitable distribution of the burden of the war.

But neither the Government had the courage to enforce these measures nor was there much possibility of success because of political factors and lack of co-operation between the Government and the public. The Government, the fore, had to content itself with a series of ill-conceived measures half-heartedly implemented.

With a view to controlling the excess demand, many new taxes such as Excess Profits Tax and Excise duties were indeed imposed while the rates of the old ones such as Corporation Tax, surcharge on Income Tax were raised. Also, a system of compulsory deposits and Pay-as-you earn in regard to Income Tax was introduced.

These measures, however, were not very successful in draining off the surplus war income because firstly, taxation as a method of mopping up extra purchasing power was used rather late. Secondly, the coverage of Income and Excess Profits taxes was narrow. Thirdly, the Government found it difficult to tax the vast agricultural sector. Finally, the intergovernmental financial relations also made it difficult if not impossible.

The need for borrowing, as a means of neutralizing the increased purchasing power, was realised at a sufficiently early stage of the war. A public loan, the Finance Minister declared is “twice blessed; it blessed him that gives and him that takes.”

Accordingly, various loans such as the war-loans and victory-loans were floated and other measures suitable for encouraging savings and absorbing large amounts from the middle and lower strata of society were introduced. The borrowing programme did not make much of a contribution because it was not properly planned and there was no whole-hearted co-operation on the part of the public.

An attempt was also made to absorb the surplus purchasing power by the sale of gold. Beginning from August 1943, a total of 7.5 million ounces were officially sold during the period of the war. To some extent, these sales drained away surplus purchasing power and thus played a useful role in controlling the menace of inflation.

One of the most serious factors contributing to inflation was the failure on the part of the Government to realise that, even in war-time, production of civilian goods can be increased. A strong well-organised production drive, backed by facility to import machinery, tools and technical advice, could have moderated the intensity of burdens imposed by inflation.

However, the Government’s Grow- More-Food Compaign, the Crop Planning Schemes and other measures to increase food production in particular did not quite succeed on account of the fact that they lacked the necessary financial and administrative support.

Early in 1945, a supply mission under the chairmanship of Sir Akbar Hydari visited U.K. to arrange for the import of several essential articles of consumption. Consumer goods, valued at roughly Rs. 150 crores, imported under the Lend-Lease Agreement from the U.S., were also helpful in adding, although marginally, to the available supplies.

It was only when inflation threatened to interfere with the war effort that the Government stepped in to impose economic controls. Control measures were applied, in particular, to cotton cloth.

A Textile Commissioner was appointed to regulate prices and control distribution. In October 1943, under the Hoarding and Profiteering Prevention Ordinance, power was taken to fix maximum prices of all articles imported or locally produced.

During 1944, statutory price control was instituted for wheat, gram, barley, bajra, jowar, and Maize. As regards rice, an All-India statutory price was not fixed but the provincial Governments themselves imposed statutory maxima. In July 1944, the consumer goods (Control of Distribution,) order was issued with the object of regulating supplies, distribution, and prices of consumer goods including imported commodities.

Under the Ordinance, prices for a large range of consumer goods were fixed. It was laid down that nothing was to be sold at prices exceeding 20% of the landed cost or cost of production. Finally, rationing of rice, wheat, sugar, and cloth was introduced mainly in districts.

The system was gradually extended to an increasing number of articles and areas and by October 1946, 771 towns and rural areas with a population of over 150 million were under rationing. It is, however, worth noting that controlled prices were not fixed in the light of such objective conditions as costs and profits.

The prices of manufactured articles brought under control were mostly negotiated prices which allowed sufficient profit to producers and distributors. Price controls, therefore, brought no more than a modest improvement in the price level.

Controls did not bring about the desired results because they were ‘uncoordinated, ill-conceived and irresolute’ lacking in popular support and also because of the absence of a coherent policy and a complete lack of the necessary personnel to enforce it.

Taken altogether, Government’s anti-inflationary measures were only negatively beneficial in so far as a further rise was checked. However, they failed miserably in bringing about any appreciable fall in prices.

Effects:

As is common during a period of inflation, the workers gained in employment but this was more than out-weighed by heavier burdens imposed by high prices. Wages never succeeded in catching up with prices. Nor was the fate of the salaried classes and those who lived on fixed income, such as pensions or on savings, any better. They too were forced to stint in respect of necessaries and economise on or forgo comforts.

The Dearness Allowance paid was so small as to be no more than a token of sympathy and good will. Finding current income insufficient, it is very likely, as B.R. Shenoy points out, that the fixed income group “might have drawn upon their past savings, liquidating their personal belongings such as gold and silver and other property.”

What was taken away from or denied to those with fixed incomes, accrued to the credit of a small minority comprising manufacturers, entrepreneurs, producers and middlemen.

The enormous increase in war-time demand, acute difficulty in imports, the absence of effective controls till 1943, and the small rise in raw-material prices gave the industrialists an opportunity to earn bumper profits. The overall index of industrial profits rose from 72.4 to 163.2.

Some might imagine that the rise in prices had opened the flood gates of prosperity for the agriculturist. That was not so. Inflation benefitted the agriculturist only to the extent to which he had surplus produce to sell. The bigger landowner gained even if allowance is made for the rise in the prices of goods which he consumed. He alone had a larger surplus to sell which he did at ever- rising prices.

With increased income, he was able to purchase more land or house-property or else he made investments in gold and ornaments. It was again he who was able to clear-off or considerably reduce his debts and redeem mortgages.

As regards the smaller landowner, he both gained and lost. Whenever he had a surplus to sell, his money income increased and he utilised it to make necessary improvements on his land provided the necessary materials were available.

As against this gain, his cost of cultivation went up because of a rise in the prices of wood, iron, and livestock. The price of his consumption articles such as cloth, kerosene, matches also went up. Transport by rail and road became more costly. On the whole, it is difficult to say that the small landowner made any definite real gain although he was perhaps able to somewhat extricate himself from his heavy obligations.

The landless labourer, however, suffered the most in some parts of the country, especially Bengal, on account of starvation and scarcity of cloth. He formed, then as now, the submerged section of rural population.

Regarding the effect of the war on rural indebtedness, the Famine Commission of Bengal observed that there was a sustained reduction in indebtedness between 1942-45, especially in the case of big and medium landholders but that the indebtedness of small holders was not reduced substantially in parts of the country.

The distress was particularly acute in Bengal where, according to Thirumalai, the percentage of indebted families rose from 31.4 in 1943 to 60 in 1946 while the debt per family increased from Rs. 87.6 to Rs. 158.

During the war, the agriculturist, however, gained in respect of fixed charges such as land revenue, or interest payments. According to an estimate made by Thomas, the debtor had to pay in 1943, only about 38% of the real value of the debt to liquidate it.

It thus appears that the larger land owners and, to a smaller extent, the middle land-owners definitely gained while the petty farmer, the landless labourer, and the village, moneylender definitely lost.

Broadly and roughly, the proportion of the country’s real wealth commanded by the big businessman, the trader, the war-profiteer, the contractor and the big supplier increased. They all made large gains in an atmosphere of general scarcity and rising prices.

The war also brought about transfer of income from the smaller towns where rationing was not in-force to the relatively more fortunate among the larger towns and cities where rationing had been introduced.

The rationed towns, where articles were sold at controlled rates, could buy a larger quantity of rationed articles with the same amount of money and the money, so saved, could buy a large amount of the non-rationed goods as well.

The war placed on the Indian people, with their low average income per head, an unbearable burden. The burden was especially heavy on the present generation which was called upon to bear the whole of it. The gains from the liquidation of past debt and the growth of sterling balances, on the other hand, opened up new opportunities for the future generations but provided little relief to the present.

The war-time inflation also resulted in the shifting of income and wealth from India to Great Britain. Had India been a free country, the British Government would have raised funds through taxes, loans and inflation for acquiring goods and services in India.

However, the method of payment in Sterling saved the British citizen from the sacrifices which additional taxation and inflation would have imposed upon him. Instead, the burden got shifted on to the back of the Indian peasant.

Prof. C.N. Vakil has compared inflation to robbery. “Both deprive the victim of some possession with the difference that the robber’s victim may be one or a few at a time, the victims of inflation are the whole nation; the robber may be dragged to a court of law, inflation is legal.”

We may add that a robber usually robs the rich, inflation mostly robs the poor. And the War-time inflation in India robbed the landless, the small farmers, the factory worker, the salaried man, and the old pensioners.

Post War Prices up to 1951, the Rising Trend:

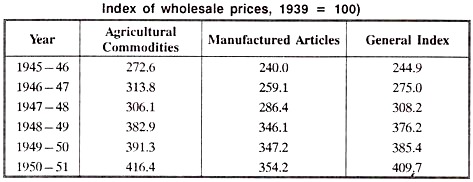

At the end of the war, it was hoped that the reduction in the war demand, availability of larger industrial capacity for civilian use, and greater imports would improve the supply position and lower the price level. Prices, however, continued to rise in the post-war period, the index of wholesale prices (1939 = 100) having reached 410 in 1950-51.

As can be seen from the table given above, the rise in prices, continuous though, was uneven. In the first phase, prices rose but at a comparatively slow pace.

In-fact, the index remained more or less steady till November, 1947 when the government decided to give up all physical controls over the prices and distribution of commodities. The price index rapidly moved upwards from 302 in November, 1947 to 389.6 in July, 1948.

The Government beat a hasty retreat; re-imposed controls and, as a result, prices came down a little. From April 1949, prices rose almost continuously, first under the impact of devaluation in September, 1949, and later, due to the out-break of war in Korea, till the index touched the record level of 410 in 1950-51.

The primary cause of this rise in prices was that despite the end of the war and the fall of defence expenditure, the budgets of both central and provincial Governments remained grossly unbalanced. The deficit became especially pronounced after August 1947, on account of the Partition, Refugee-Relief, war in Kashmir, and the Police Action in Hyderabad.

In addition, on account of the new development plans which were put into operation, the expenditure of the provinces tended to exceed their receipts. Between 1946-47 to 1950-51, the central government alone incurred a deficit of Rs. 306.18 crores, both on revenue and capital account.

This led to a corresponding expansion of money-supply with the public. This, in turn, led to an expansion of scheduled banks’ credit which rose from Rs. 310.12 crores in 1945-46 to Rs. 442 crores in 1949-50.

Against this expansion of purchasing power, there was actually a decline in the output of many industrial and agricultural commodities. The index of industrial production (1937 = 100) declined from 120 in 1945 to 102.4 in 1947 but rose to 114 in 1948. The fall in industrial production was caused, among other things, by labour troubles, the difficulty of obtaining machinery and raw-materials and threats of nationalisation.

A contributory factor was the policy of decontrol tried under advice from Mahatma Gandhi. Food-grains had been decontrolled in December, 1947. Sugar had been decontrolled earlier and cloth soon followed suit.

The immediate effect of this policy, according to Mr. P.K. Mukerjee , was “to bring the latent inflation into the open” raising prices to still higher levels. This may be seen from the fact that, during the eight months following the removal of controls, there was a 32.5% rise in the prices of food articles, 19.1% in raw materials and 30.7% increase in manufactured goods.

Devaluation of the rupee, effected in September 1949, stimulated a further rise in prices. Firstly, prices of imports from the dollar area rose by 44% and secondly, expansion of exports, which followed devaluation, created a relative scarcity of goods which had a further inflationary effect. Devaluation was followed by the outbreak of the Korean War in June, 1950.

It led to a feverish stock-piling programme in all countries, which, together with a sudden increase in speculative and hoarding activity, pushed up the prices, especially of raw-materials. This may be seen from the fact that the prices of the raw materials group went up by 39.2% as against a rise of 2.4% in the food group and 18.4% in the manufactured articles group.

In-order to meet the situation, the government announced an anti-inflationary policy in October, 1948 which comprised re-imposition of controls on food grains and other essential commodities, bringing the budgetary deficit down by reducing expenditure and increasing revenues, raising agricultural and industrial production by such incentives as tax relief, liberalisation of depreciation allowances, tax-exemption for new industrial undertakings for a certain period, reduction of import duty on plant and machinery as well as essential raw-materials.

Small savings were encouraged and profits were limited. This anti-inflationary policy had a very limited success as “it lacked vigour and efficiency in its execution.”

Following the devaluation of the rupee in October 1949, a further eight-point programme was announced ‘to hold the price line’. It included the prevention of speculative price-rise by administrative and legislative measures, regulation of credit facilities, action to stimulate investment and secure reduction in government’s expenditure.

A compulsory savings Scheme for government employees was also introduced. A still more comprehensive programme was announced in August 1950, in order to meet the situation arising from the Korean War. These measures, helped by certain international developments, though exercised a steadying influence on the general trend of prices, could not arrest their upswing.

Inflation of Growth, 1951-1966:

In 1951, when India embarked on the voyage of planned development, Indian prices entered a new era wherein they scaled heights unimaginable before. One of the objectives of the First plan was to contain the inflationary pressure generated during the war and post-war period. Investment programmes were, therefore, drawn up with strict regard to realisable savings.

No wonder, the Plan was criticised for lacking the during features of development and condemned “as a stability plan rather than a development Plan.” Aided by bumper harvests, the plan largely succeeded in realising its aim, the index number of wholesale prices declined from 125.2 in 1951 to 98.1 in 1956 (1952-53 = 100).

It may be, however, noted that the declining trend in prices was not uniformly maintained throughout the length of the plan. Rather, the price level showed wide fluctuations. With the end of the Korean war and following the disinflationary fiscal and monetary measures taken during 1951, prices recorded a marked fall, the index coming down from 125.2 in March 1951 to 99.9 in March, 1952.

The index remained steady, more or less, around this level for the next two years when the bumper crop of 1953-54, resulted in a sharp fall in prices, especially of food-grains and the price index slumped to 94 in March, 1955. From July 1955, an upward trend in prices emerged which continued for the rest of the Plan period, the index touching 98.1 in 1956.

A noteworthy feature of the price-trends during the First Plan was that the decline in prices was not equally shared by all commodities. The maximum fall was registered by industrial raw-materials whose prices declined by 28.8% while the prices of manufactures fell the least by 13.3%.

Thus, the First Plan was launched in a period of inflation and it was completed when price support measures had become necessary for major agricultural products.

The Second Plan was characterised by a persistent upward trend though a part of the rise was a corrective to the earlier decline. The index number of whole-sale prices rose from 98.1 in 1956 to 127.5 in 1956.

Over the five-year period, 1956-61, the overall increase in wholesale prices was about 30%; the industrial raw-materials rose the maximum by 45%, food articles, as a group, increased by 27% while manufactures rose by over 25%.

Relative shortage of food- grains was the major factor accounting for price-rise in the early stages of the plan, whereas, in the later years, the leading factor was the shortage of agricultural raw-materials. The rise in the prices of manufactures was the consequence of the rise in raw-material prices.

The rise in prices during the first and Second Plans was not as considerable as was expected and India was able to complete the first two plans without anything in the nature of real inflation. Even in the first two years of the Third Plan, the price level was relatively stable, the annual average rise being only 2.4%.

Industrial raw-materials contributed the most towards this price stability, their index remaining steady at 134.7 in March, 1962 and 135.3 on 31 March, 1963. Prices, however, resumed their upward trend during the last three years of the Third Plan when they rose at the annual rate of 8.9% as compared with a 5.9% annual increase during the 10-Year period 1956-57 to 1965-66.

During the Third Plan, as a whole, prices of all commodities rose by 32% accounted for largely by the 40.7% rise in the prices of food articles.

One note worthy feature of the price movements during the plan period was the relative stickiness of prices. As a result of Government regulation, improved storage and marketing facilities, the post-harvest decline tended to be much smaller than the rise in the preceeding lean season. This led to a cumulative rise in the price level.

Secondly, India, being an agricultural country, the general price behaviour was more influenced by the performance of the agricultural sector. Prices invariably short up whenever agricultural production was adversely affected. For instance, food articles and industrial raw-materials were together responsible for about 3/4 of the increase in the general price level in 1964-65.

Causes:

Sindey Weintraub , advocating the wage — Income Theory of prices, has held the phenomenon of larger increases in wages, far in excess of the increase in the average level of labour productivity, as almost exclusively responsible for the persistent rise of prices in India.

This could be a plausible explanation and wage — cost constituted a major portion of the total cost in industry and if it could be shown that wage-income formed a substantial portion of national income.

In reality, however, wage-cost in major industries in India constituted a small proportion of the total cost. And what is more significant, money-wage, as a percentage of national income, remained static at 2% between 1950-61. The insignificant ratio of wage-earning to national income excludes any possibility of price rise through an increase in wages.

Prices rise or fall due to excess or deficiency of demand over supply. In India since 1951, and particularly since 1956, the major cause of the increase in prices was the excess of demand. Government’s expenditure, both plan and non-plan, steadily increased over the Plan period.

The increase in the non-plan expenditure, especially in the wake of the Chinese aggression and the conflict with Pakistan in 1965, added to the aggregate demand without increase in real output. On the investment, both public as well as private, created money incomes ahead of output creation.

The longer the period of gestation for any dose of investment, larger was the gap between the creation of money incomes and output. There, however, existed neither accumulated stocks of goods nor much of unutilised capacity which could absorb the increased aggregate demand. Accordingly, the pressure on prices rose with every increase in the volume of investment.

If this increased investment had been balanced by savings, current or part, or by foreign aid, monetary circulation would have been left unaffected.

However, from the very beginning, reliance was placed upon deficit-financing, which B.R. Shenoy, regards as “the best subsidy to communism.” The official view was that “deficit — financing, subject to safeguards, has a definite part to play in bringing into use the un-utilised resources in the system.”

This was endorsed by the I.M.F. mission “which visited India in 1953. Price rise, it was agreed, is inevitable but it was held that “price stability can’t be an end in itself, particularly if this can be attained only by restricting the incomes of the large mass of the people.” But as planning progressed, safety was thrown to the winds; deficits in successive budgets were treated with impunity and the depletion of the cash reserves did not alarm the authorities.

During the First Plan, deficit-financing amounted to Rs. 420 crores —a part of which was financed by drawing on the cash balances of the central government. This comparatively mild dose was absorbed by the economy, helped as it was by good monsoons and a buoyancy in the industrial sector.

The Planners felt emboldened. During the Second Plan, a bigger dose of deficit financing Rs. 949 crores —was administered while in the Third Plan, it came to Rs. 1133 crores.

These ever-mounting deficits were financed by borrowing from the Reserve Bank by way of loans and advances or by sale of government securities and Treasury Bills to the Reserve Bank which issued new currency notes. The government also secured funds by selling securities to the commercial banks.

The result was the expansion of currency and bank deposits and increase, with the public, of money supply which rose at a compound annual growth rate of 6.6% in the Second Plan and 9.6% during the Third Plan.

It is an error to argue, as the official circles did , that the expansion effects of deficit-financing and credit creation by commercial banks were, to a large extent, offset by the increase in the time deposits of the banks B.R. Shenoy points out that, “Time deposits are not a monetary sink down which inflationary funds may disappear from circulation.”

Like other resources accruing to banks, time deposits also get restored into circulation as and when banks acquire other assets against them.

It does not mean that all monetary expansion led to inflation. Some monetary expansion was indeed necessary for growth with stability. As production increased, money supply had to grow in order to support the growing volume of production. The expansion, however, was far beyond the safe limits of what the economy could absorb. The created money caused an artificial not a natural- upward ‘pull of demand’.

Besides, expanded investment of this nature was undertaken at a time when it was not able to contribute much to increased production. The money incomes of the public, therefore, grew faster than the national product and the prices rose.

The pressure of demand was further accentuated by rapid increase in population. During the First Plan, the annual increase of 1.7% in population was more than matched by a 4.2% increase in agricultural production. During the Second Plan, however, while the annual rate of increase in population rose to 2.1%, increase in agricultural production remained almost stationary at 4.3%.

The situation further worsened during the Third Plan when the gap between population, which annually increased at the rate of 2.4%, and agricultural production, which declined by 7.4%, became very wide.

Infact, production of wheat, Jawar and rice in 1965-66 was less than that in 1960-61. This growing rate of population increase, placed against a declining supply, offers “a major explanation of the continued uptrend in wholesale prices.”

The sustained inflationary pressures were doubtless due to an excess of demand. But this, by itself, would not have resulted in the inflationary situation without the major failure on the supply side. Had supply been increased to correspond with demand, there would have been no possible reason for prices to go up.

This is precisely what happened during the First Plan when though all the factors on the demand side were present, but the increase in production of agricultural goods was so much that there was no rise in prices. They actually declined. During the II and III plan, inducement to price increase came chiefly from the inelastic supply, especially of agricultural production.

Unfortunately, the domestic production was beset with a sectoral imbalance between agriculture and industry. Industry expanded at a much faster rate thereby creating a chronic shortage of food and raw-materials. The overall growth rate in industry in the first two plans was 7% but it rose to 8.2% in the Third.

In contrast, agricultural production rose at a cumulative rate of 3.5% per annum in the first two plans and by only 2.5% per annum during the Third. Taking the period of the three plans together, the growth rate in food production works out at 2.3%.

As a result of this sectoral gap between industry and agriculture, the increase in demand on account of the increase in incomes, population and urbanisation led to a rise in agricultural prices.

As such, inflation in agriculture was in the nature of ‘demand —pull’. But a different situation obtained in industry where the rise in food prices led to an increase in wages and allowances. This, added to the high prices of raw-materials, raised the cost of manufactures. In other words, inflation in industry was largely cost-push.

Not only was agricultural production short of demand, but significantly, whatever was produced was not brought to the market for sale. Tendency to restrict supplies to the market so as to earn high prices turned many rich cultivators into cultivator traders.

This tendency was best seen in the Third Plan when the proportion of market arrivals of rice to the estimated marketable surplus, which averaged 12% per year in the first two years, declined to 7% in the last years.

The corresponding proportions for wheat were 11% and 5% and for jowar 5% and 4%. This may sound strange because normally, increased production and higher prices should lead to a corresponding expansion of marketed supplies.

This, however, did not happen because:

(a) There was more self-consumption on the part of the producers;

(b) A tendency had developed for holding grains in anticipation of further rise in prices;

(c) The producers’ need for cash could be met with lower sales;

(d) Rising prices generated a tendency to prefer payment in goods rather than money at harvest time, thus adversely affecting marketable surplus. The operation of these factors accounts for the situation in which less produce was brought to the market for sale when prices rose.

The shortage of food was aggravated by a rise in its demand for purposes of precautionary and speculative stock- building; both by consumers as well as traders. Mounting development expenditure, financed by the creation of new money, coupled with inelasticity of food-grains, provided a great stimulus to such tendencies which further reduced the supplies available to the consumers.

Finally, the role of the Black Money in pushing up the prices can’t be underestimated. Although it is difficult to evaluate its precise impact, there is no doubt that it played an important role. It may be remembered in this connection, that the purchasing power of black money declines much faster than that of the accepted legal tender.