In this article we will discuss about the merits and uses of indifference curve approach.

Merits of Indifference Approach:

Indifference (Preference) approach to utility analysis is considered to be superior to neo-classical cardinal utility analysis. The apparatus can explain, it has been argued, all the theories of consumer behaviour with lesser number of assumptions. There is no need to assume that utility can be measured by money. Utility is measurable in a more rational way by the behaviour of consumer.

Nor is it necessary to assume that the marginal utility of money is constant. Indeed, these basic assumptions of cardinal utility are unrealistic and the ordinal utility analysis has avoided them without failing to explain any of the theorems relating to consumer’s behaviour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Secondly, utility of a good in cardinal analysis was thought to be a function of that good only. In other words, utility was an independent function. In real life, it is far from true. The origin of indifference curve lies in this weakness of the cardinal utility theory.

It was invented to study related goods. It shows the art of maximising utility among combinations of two goods or, as Hicks has suggested innumerable goods on one axis and money on the other.

Further, another achievement of the ordinal utility analysis is its analysis of consumers’ demand by income effect and substitution effect.

The Marshallian demand curve has been segregated into two separate curves — the income consumption curve and the price consumption curve.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

By their differentiation between income-effect and substitution-effect, the ordinalists have been able to resolve the Giffen Paradox — a theoretical enigma to Marshall.

It highlights the importance of income-effect in explaining the effects of a change in price on quantity demanded. The concept of negative income effect is helpful in explaining inferior goods.

Uses of the Indifference Curve Approach:

Indifference curve techniques were not developed just to confuse students of economics. They do offer a more penetrating analysis of consumer demand than simple demand curves and they are of considerable importance in the study of advanced economic theory. So, it is worthwhile to make the effort and really try to understand them. It is convenient at this point to examine two uses, other than the analysis of effects of changing prices and incomes, that may be made of the curves.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) Inflation:

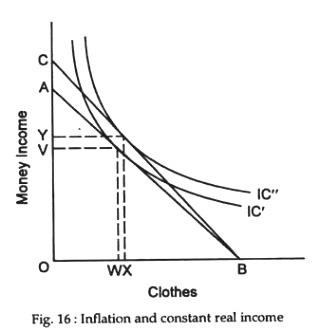

Indifference curves demonstrate the effects of inflation or the situation in which prices and incomes are rising. When prices rise consumers must secure a rise in money incomes in order to maintain their real income and their standard of living. A 10 per cent rise in prices has to be accompanied by a 10 per cent rise in money income if consumers are not to suffer a fall in real income. Fig.16 reveals a more subtle change.

With his original income OA the consumer had a budget line AB and chose to buy OW units of clothes and spend OV on other goods. If his income rises by 10 per cent to compensate for a 10 per cent rise in prices he can still buy a maximum of OB units of clothes but his budget line moves to CB, enabling him to buy OX units of clothes and retain OY units of money. He therefore moves to a higher indifference curve, even though his real income is constant.

The higher money income gives greater satisfaction. Although real incomes are not higher, as the money incomes will buy only the same quantity of real goods, the consumer is deluded into buying more as the extra money has less utility, and he thinks the residue larger than it actually is. This is one way in which inflation distorts the pattern of expenditure. Other effects of inflation are considered in Unit Twenty- three.

If the price of clothes rose and there was no compensating rise in income the budget line would have become steeper and forced the consumer to a lower indifference curve. This would reduce his living standards and this is the normal effect of inflation.

(b) Taxation:

In Fig. 17 a comparison is made between the relative effects of income taxes and expenditure taxes.

In this absence of taxation we can assume that the consumer is at a buying OB units of clothes and OC units of other goods. If a tax is imposed on consumer to point b on IC1. At this point he buys OG units of clothes and spends OD units on other things. Before the tax was imposed the consumer could have combined OG units of clothes with OL units of money income or other goods as we can see from the budget line AE.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The tax has therefore reduced his real income by LD. This could equally well have been achieved by the imposition of an income tax equivalent to LD, when the consumer to move to c on IC2 which is preferable to the position b that the expenditure tax leaves him in. He is able to enjoy GJ more of clothing than he could when clothes were taxed.

While this is true for the individual whose indifference map we have drawn, it is not necessarily true for all consumers and so we cannot on the basis of this analysis argue that income taxes are preferable to expenditure taxes.