In his pamphlet ‘How to pay for the War’ published in 1940, Keynes explained the concept of the inflationary gap. It differs from his views on inflation given in his General Theory. In the General Theory, he started with underemployment equilibrium. But in How to Pay for the War, he began with a situation of full employment in the economy. He defined an inflationary gap as an excess of planned expenditure over the available output at pre-inflation or base prices.

According to Lipsey, “The inflationary gap is the amount by which aggregate expenditure would exceed aggregate output at the full employment level of income.” The classical economists explained inflation as mainly due to increase in the quantity of money, given the level of full employment. Keynes, on the other hand, ascribed it to the excess of expenditure over income at the full employment level.

The larger the aggregate expenditure, the larger the gap and the more rapid the inflation. Given a constant average propensity to save, rising money incomes at full employment level would lead to an excess of demand over supply and to a consequent inflationary gap. Thus Keynes used the concept of the inflationary gap to show the main determinants that cause an inflationary rise of prices.

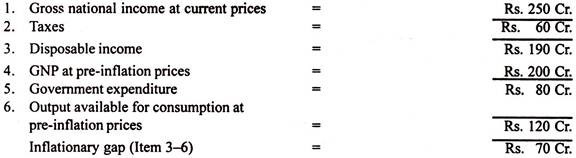

The inflationary gap is explained with the help of the following example:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Suppose the gross national product at pre-inflation prices is Rs. 200 crores. Of this Rs. 80 crores is spent by the government. Thus Rs. 120 (Rs. 200-80) crores worth of output is available to the public for consumption at pre-inflation prices.

But the gross national income at current prices at full employment level is Rs. 250 crores. Suppose the government taxes away Rs. 60 crores, leaving Rs. 190 crores as disposable income. Thus Rs. 190 crores is the amount to be spent on the available output worth Rs. 120 crores, thereby creating an inflationary gap of Rs. 70 crores.

This inflationary gap model is illustrated as under:

In reality, the enitre disposable income of Rs. 190 crores is not spent and a part of it is saved. If, say 20 per cent (Rs. 38 croes) of it is saved, then Rs. 152 crores (Rs. 190-Rs. 38 crores) would be left to create demand for goods worth Rs. 120 crores. Thus the actual inflationary gap would be Rs. 32 (Rs. 152-120) crores instead of Rs. 70 crores.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

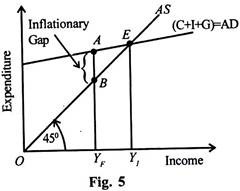

The inflationary gap is shown diagrammatically in Figure 5 where OYF is the foil employment level of income, 45° ine represents aggregate supply AS and C + 1 + G line the desired level of consumption, investment and government expenditure (or aggregate demand curve). The economy’s aggregate demand curve (C + l + G) = AD intersects the 45° line (AS ) at point E at the income level OF, which is greater than the full employment income level OYF.

The amount by which aggregate demand (YFA) exceeds the aggregate supply (YFB) at the foil employment income level is the inflationary gap. This is AB in the figure. The excess volume of total spending when resources are fully employed creates inflationary pressures. Thus the inflationary gap leads to inflationary pressures in the economy which are the result of excess aggregate demand.

The inflationary gap can be wiped out by increase in savings so that the aggregate demand is reduced. But this may lead to deflationary tendencies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Another solution is to raise the value of available output to match the disposable income. As aggregate demand increases, businessmen hire more labour to expand output. But there being foil employment at the current money wage, they offer higher money wages to induce more workers to work for them. As there is already foil employment, the increase in money wages leads to proportionate rise in prices.

Moreover, output cannot be increased during the short run because factors are already folly employed. So the inflationary gap can be closed by increasing taxes and reducing expenditure. Monetary policy can also be used to decrease the money stock. But Keynes was not in favour of monetary measures to control inflationary pressures within the economy.

Despite these criticisms the concept of inflationary gap has proved to be of much importance in explaining rising prices at foil employment level and policy measures in controlling inflation.

It tells that the rise in prices, once the level of foil employment is attained, is due to excess demand generated by increased expenditures. But the output cannot be increased because all resources are fully employed in the economy. This leads to inflation. The larger the expenditure, the larger the gap and more rapid the inflation.

As a policy measure, it suggests reduction in aggregate demand to control inflation. For this, the best course is to have a surplus budget by raising taxes. It also favours saving incentives to reduce consumption expenditure.

“The analysis of the inflationary gap in terms of such aggregates as national income, investment outlays and consumption expenditures clearly reveals what determines public policy with respect to taxes, public expenditures, savings campaigns, credit control, wage adjustment—in short, all the conceivable anti-inflationary measures affecting the propensities to consume, to save and to invest which together determine the general price level.”