Classical Trade Theory: A Close View!

The Basis of Trade: Classical Trade Theory:

Why do different countries trade with each other? As trade benefits them, they trade with each other. Why does gain from trade arise? The gain from trade arises because of specialization in production and division of labour. Individuals specialize, firms specialize in certain products. Same is true for the countries. That is why each country is interested in exchanging its own specialized products for non-specialized products. But which products should a country specialize in? Classical economists answered this question.

According to classical writers, differences in cost form the basis of trade.

Differences in cost may be two types:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) Absolute cost difference, and

(ii) Comparative cost difference.

In 1776, Adam Smith argued that the absolute cost difference or absolute advantage is the basis of trade. But another classical economist, David Ricardo, went a step forward in 1817 to search the basis of trade in terms of comparative cost difference or comparative advantage.

Smith argued that a country will export that commodity in which it has an absolute advantage and import that commodity in which it has an absolute disadvantage. According to Ricardo, a country will produce and export that commodity in which it has a comparative advantage and will import that commodity in which it has a comparative disadvantage.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In explaining their trade theory, classicists made the following assumptions:

i. There are two countries, two commodities and one factor; i.e., a 2 × 2 × 1 model.

ii. Labour theory of value holds. Classicists argued that labour is the only productive input as far as the value of a commodity is concerned. Value of a commodity is determined by the amount of labour embodied in it. Thus, production cost is measured in terms of labour costs only.

iii. Production function obeys constant returns to scale. In other words, output per unit of labour is constant over all relevant ranges of the production function.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iv. Inputs, although mobile domestically, are completely immobile internationally.

v. Transport cost is zero.

vi. Free trade policy is pursued.

Adam Smith’s: Absolute Advantage Doctrine:

According to Adam Smith, it is the difference in absolute production cost that causes the emergence of trade. A country has an absolute advantage over another country in the production of a good if it can produce it at a lower cost. It would, thus, be advantageous for the country if it specializes in the production of cheapest good. Smith argued that a country would produce and export that commodity in which it has an absolute advantage or lower cost and import that commodity in which it has an absolute disadvantage or higher cost.

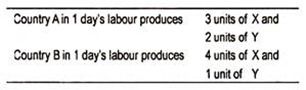

The following example will help explain Smith’s absolute cost differences. Let us assume that there are two countries, A and B that produce two goods X and Y which require labour for their production. Further, suppose that country A takes 1 day’s labour to produce 3 units of X and 2 units of Y. Country B produces 4 units of X and 1 unit of Y by the same labour cost.

Clearly, country A has an absolute advantage in the production of Y since it can produce it at a lower cost than country B. While country B has an absolute advantage in the production of X. In the absence of trade (i.e., under autarky or no trade) in country A, 3 units of X will exchange for 2 units of Y and in country B 4 units of X will exchange for 1 unit of Y.

Thus, internal and domestic exchange ratio between two goods of country A is 3: 2 and for B it is 4:1. Country A will now benefit if it can produce and export good Y to buy more than 2 units of Y. Similarly, country B will gain more by producing and exporting X from A by buying more than 4 units of X. Clearly, both countries will gain. Anyway, trade is mutually beneficial since it increases both production and consumption.

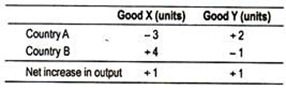

Because of trade, productions of both X and Y will increase in the following pattern:

Thus, international trade is mutually beneficial. Global output and consumption of both X and Y have increased at least 1 unit in each country.

David Ricardo’s: Comparative Advantage Doctrine:

Ricardo has demonstrated that absolute cost advantage is not a necessary condition for the two countries to gain from trade. Instead, he concluded that trade would also benefit both the nations if comparative costs differ.

To him, comparative difference in cost is a sufficient condition for trade to emerge. Ricardo’s doctrine states that a country will export that commodity in which it has a comparative advantage and import that product in which it has a comparative disadvantage.

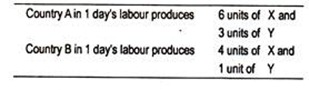

The following example suggests that the developed country A has an absolute advantage in the production of both goods X and Y. Nevertheless, country A can gain from trade with the less developed country B because it has a cost advantage in the production of Y over X. In contrast, poor country B has a comparative advantage in the production of X.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Pre-trade exchange ratios for A and B are 1 X for 2 Y (i.e., 6 for 3) and 1 X for 4 Y. In other words, Y is cheaper in A while X is cheaper in B. So, A should export Y while B should export X, each specializing in that commodity in which it has a comparative advantage.

Before trade, let us assume that country A transfers all labour from the production of X to the production of Y in which its pre-trade opportunity cost (1: 2) is lower and country B shifts all labour from the production of Y to the production of X in which its pre-trade opportunity cost (1: 4) is lower.

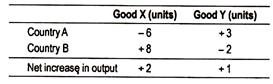

Now country A enjoys lower comparative cost in the production of Y, while country B enjoys the same in the production of X. Labour will now be transferred form X-production to Y-production in country A while labour will be transferred from Y-production to X-production in country B. As a result, production of X will decline in country A by 6 units while production of Y will increase by 3 units.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At an international exchange rate of 1: 3 (lying between two domestic exchange rates of 1: 4 and 1: 2) country A will now export 3 units of Y and import 9 units of X. Before trade, country A consumed 6 units of X, and after trade it consumes additional (9 – 6 =) 3 units of X. This is called ‘gains from trade’.

Likewise, country B gains from trade. As country B transfers labour from Y-production to the X-production, Y output declines by 1 unit. But as labour is transferred to the X- production, X-output rises by 4 units. Country B now trades with A at an exchange rate of 1: 3 by exchanging 1 unit of X for 4/3 = 1⅓ units of Y. As a result of trade, country B consumes additional ⅓ units of Y. This is known as ‘gains from trade’.

The result will be:

We have learnt that the internal terms of trade in country A and in B is 1: 2 in country A and 1: 4 in B. Both countries will now gain from this specialization in trade if exchange rate or post-trade terms of trade lies between two internal or domestic exchange rates, i.e. between 1: 2 and 1:4. Let the international terms of trade be 1: 3.

At this new exchange rate, A will specialize in the production of Y. Now, by exporting Y, it will bring more X. As soon as country A transfers labour from X-production to the Y- production and country B from Y-production to the X-production, there occurs complete specialization. This kind of specialization results in more global output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, Ricardo’s comparative cost doctrine demonstrates the basis of trade, direction of trade and gains from trade.

Graphical Representation of Ricardo’s Doctrine:

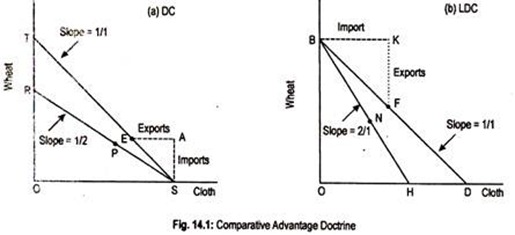

Ricardo’s doctrine of comparative cost can also be explained in terms of production possibility curve that gives the maximum producible amount of commodities (say, wheat and cloth) that an economy can produce. RS is the production possibility curve of DC and BH is of LDC. Since constant cost conditions prevail, the production possibility curve is a straight line—implying constant opportunity costs of production.

The slope of this line indicates constant domestic or pre-trade price or constant terms of trade. Pre-trade terms of trade or exchange rate in DC is 1 wheat for 2 cloth, i.e., 1W: 2C, and that for LDC is 2W: 1C. This is indicated by the production possibility curves RS and BH for both DC and LDC, respectively.

RS has a slope of 1W: 2C (or 1/2) and BH has a slope of 2W: 1C (or 2/1). Let P be the production and consumption point of DC before trade. Since DC has a comparative advantage in cloth production, after trade it will produce at point S. Thus, it produces cloth only and no wheat.

DC experiences a complete specialization in the production of cloth. Similarly, LDC’s pre-trade production and consumption point is N. After trade, its production point shifts to B implying that it specializes in the production of wheat. Thus, trade enables each country to produce more than what it produces domestically.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For simplicity’s sake, we are assuming that international terms of trade or post- trade exchange rate is 1W: 1C—an intermediate rate that exists between 2W: 1C and 1W: 2C. To demonstrate this new exchange ratio, we have drawn line TS in Fig. 14.1(a) whose slope is 1W: 1C (or 1/1) and BD in Fig. 14.1(b) whose slope is also 1W: 1C (or 1/1).

This new term of trade line enable each country to consume more. Consumption point of DC shifts to point E on the TS line. This means that DC now consumes more of cloth and more of wheat. It exports its surplus cloth production EA to buy AS amount of wheat. Similarly, as a result of trade the LDC’s consumption point shifts to F. This means that it sells its excess production KF amount of wheat to buy KB of cloth from DC. At point F, LDC consumers, of course, get more of both wheat and cloth.

Thus, trade enables each country to specialize in the production of a commodity in which it has a comparative advantage. Further, trade enables each partner to consume more.

Remember that Ricardo did not specify the exact terms of trade at which trade would take place. His terms of trade ratio lies between the two domestic terms of trade ratios. The exact ratio that would govern trade was left undetermined.

Limitations:

This theory has been criticized on many grounds. Important criticisms against this theory are:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. Unrealistic Assumption of Labour Theory of Value:

Firstly, one of the fundamental assumptions of the classical trade theory is the labour theory of value. This theory states that the relative costs of production are determinded by the labour costs alone. The assumption of the labour theory of value seems to be unrealistic in explaining the cause of trade. Modern economists have discarded the labour theory of value and employed opportunity cost theory. Opportunity cost theory rescues Ricardo’s doctrine without altering its basic conclusion.

ii. Differences in Comparative Costs not Explained:

Secondly, Ricardo could not explain why do comparative costs differ between countries. Answer to this question was given by Eli F. Heckscher and B. Ohlin who suggested that differences in factor endowments and factor-intensity give rise to differences in comparative costs.

Let us assume that the country A uses more capital in the production of a commodity than country B. If use of capital per unit of labour in country A is higher, then country A is a capital-abundant country. On the other hand, let us assume that the country B is a labour-rich country.

In our example, we have seen that country A specializes in the production of Y as it has comparative advantage in Y-production. Since country A is a capital-intensive country, Y-production here becomes more capital-intensive. Likewise, country B has the comparative advantage in the production of X.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Being a labour-rich country, country B’s production of X becomes more labour-intensive. Heckscher and Ohlin argue that a country will specialize in the production and export those goods whose production requires a relatively large amount of the factor in which the country is relatively well-endowed (i.e., the more abundant factor). As country A, in our case is a capital-rich country, it specializes in the production of Y (comparative costs of Y are cheaper).

Since country B is a labour- abundant country, it comparative costs are lower in X-production and, hence, its exports the X for Y. Thus, differences in factor endowments and factor intensity explain the differences in comparative cost. Ricardo simply took for granted that labour cost ratios differ.

iii. Exact terms of Trade Undetermined:

Thirdly, Ricardo could not determine the exact terms of trade or exchange rate at which trade takes place. Ricardo’s terms of trade (TOT) would lie between the countries’ pre-trade terms of trade; but the exact ratio was left undetermined. This gap was filled by the classical author J. S. Mill by introducing the concept of ‘reciprocal demand’ in trade theory. Ricardo’s model concentrates on the supply (or cost) side and, hence, it neglects the demand side.

iv. Zero Transport Cost is Inconceivable:

Fourthly, Ricardo neglects transport, cost just for simplicity. It is true that transport costs are important in determining the exchange rate. Supporters of Ricardo’s doctrine have adequately demonstrated that transport costs do not affect comparative cost doctrine.

v. Trade is Multi-Lateral and Multi- Good:

Fifthly, for simplicity’s sake, Ricardo’s model is the 2 x 2 x 1 model, But if we apply Ricardo’s theory in case of more than two countries and more than two commodities, conclusions of the doctrine remain virtually unaltered.

Conclusion:

In analysing his trade doctrine, Ricardo started with the unreal world. Some of the writers fit this theory in the real world without altering its fundamental conclusions. Some of his assumptions were questionable. Modern writers removed those assumptions and refined this doctrine. Only the gaps in the Ricardian model have been filled up by the modern writers. A doctrine propounded about 200 years ago is even now respected by all, possibly because of its originality.