This article highlights the two major types of differences in cost that forms the basis of trade.

1. Adam Smith’s Absolute Advantage Doctrine:

According to Adam Smith, it is the difference in absolute production cost that causes the emergence of trade. A country has an absolute advantage over another country in the production of a good if it can produce it at a lower cost.

It would, thus, be advantageous for the country if it specialises in the production of a cheapest good. Smith argued that a country would- produce and export that commodity in which it has an absolute advantage or lower cost and import that commodity in which it has an absolute disadvantage or higher cost.

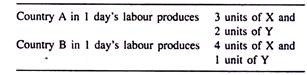

The following example will help explain Smith’s absolute cost difference. Let us assume that there are two countries, A and B, that produce two goods X, and Y, which require labour for their production. Further, suppose that country A takes 1 day’s labour to produce 3 units of X and 2 units of Y. Country B produces 4 units of X and 1 unit of Y by the same labour cost. Clearly, country A has an absolute advantage in the production of Y since it can produce it at a lower cost than country B and country B has an absolute advantage in the production of X.

In the absence of trade (i.e., under autarky or no trade), in country A, 3 units of X will exchange for 2 units of Y and in country B, 4 units of X will exchange for 1 unit of Y. Thus, internal and domestic exchange ratio between two goods of country A is 3: 2 and for B it is 4: 1. Country A will now benefit if it can produce and export good Y to buy more than 2 units of Y. Similarly, country B will gain more by producing and exporting X from A by buying more than 4 units of X. Clearly, both countries will gain. Anyway, trade is mutually beneficial since it increases both production and consumption.

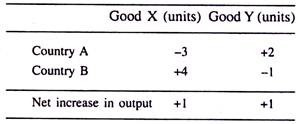

Because of trade, production of both X and Y will increase in the following pattern:

Thus, international trade is mutually beneficial. Global output and consumption of both X and Y have increased by at least 1 unit in each country.

2. David Ricardo‘s Comparative Advantage Doctrine:

Ricardo has demonstrated that absolute cost advantage is not a necessary condition for the two countries to gain from trade. Instead, he concluded that trade would also benefit both the nations if comparative costs differ. To him, comparative difference in cost is a sufficient condition for trade to emerge. Ricardo’s doctrine states that a country will export that commodity in which it has a comparative advantage and import that product in which it has a comparative disadvantage.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

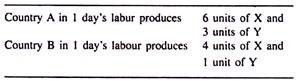

The following example suggests that the developed country A has an absolute advantage in the production of both goods X and Y. Neverthless, country A can gain from trade with the less developed country, B, because the former has a cost advantage or a comparative advantage in the production of Y over X. In contrast, the poor country B has a comparative advantage in the production of X.

In Other words, in country A good Y is relatively less expensive compared to country B. Similarly, in country B good X is relatively less expensive than country A.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Pre-trade exchange ratios for A and B are 1 X for 2 Y (i.e., 6 for 3) and 1 X for 4 Y. In other words, Y is cheaper in A while X is cheaper in B. So, A should export Y while B should export X, each specialising in that commodity in which it has a comparative advantage.

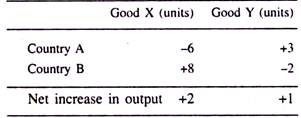

Before trade, let us assume that country A transfers all labour from the production of X to the production of Y in which its pre-trade opportunity cost (1: 2) is lower and country B shifts all labour from the production of Y to the production of X in which its pre-trade opportunity cost (1 : 4) is lower. As a result, production of X will decline in country A by 6 units while production of Y will increase by 3 units.

At an international exchange rate of 1: 3 (lying between two domestic exchange rates of 1: 4 and 1: 2), country A will now export 3 units of Y and import 9 units of X. Before trade, country A consumed 6 units of X, and after trade it consumes additional (9 – 6 = 3) units of X. This is called ‘gains from trade’.

Likewise, country B gains from trade. As country B transfers labour from Y-production to the X-production, Y output declines by 1 unit. But as labour is transferred to the X-production, X- output rises by 4 units. Country B now trades with A at an exchange rate of 1: 3 by exchanging 1 unit of X for 4/3 = 1 1/3 units of Y. As a result of trade, country B consumes additional 1/3 unit of Y. This is known as ‘gains from trade’.

The result will be:

We have learnt that the internal terms of trade in country A and in B is 1: 2 in country A and 1: 4 in B. Both countries will now gain from this specialisation in trade if exchange rate or post- trade terms of trade lies between two internal or domestic exchange rates, i.e., between 1: 2 and 1: 4. Let the international terms of trade be 1:3. At this new exchange rate, A will specialise in the production of Y. Now, by exporting Y, it will bring more X. As soon as country A transfers labour from X-production to the Y-production and country B from Y-production to the X-production, there occurs complete specialisation. This kind of specialisation results in more global output.

Thus, Ricardo’s comparative cost doctrine demonstrates the basis of trade, direction of trade and gains from trade.

Graphical Representation of Ricardo’s Doctrine:

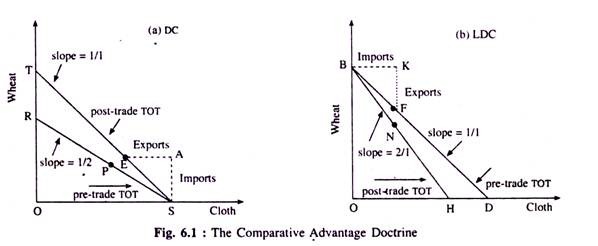

Ricardo’s doctrine of comparative cost can also be explained in terms of production possibility curve that gives the maximum producible amount of commodities (say, wheat and cloth) that an economy can produce. RS is the production possibility curve of a DC and BH is of an LDC.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

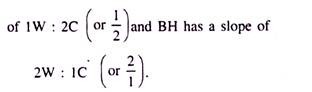

Since constant cost conditions prevail, the production possibility curve is a straight line— implying constant opportunity costs of production. The slope of this line indicates constant domestic or pre-trade price or constant terms of trade (TOT). The pre-trade terms of trade or the exchange rate in DC is 1 wheat for 2 cloth, i.e., IW: 2C, and that for LDC it is 2W : 1C. This is indicated by the production possibility curves RS and BH for both DC and LDC. respectively. RS has a slope

Let P be the production and consumption point of the DC before trade. Since the DC has a comparative advantage in cloth production, after trade it will produce at point S. Thus, it produces cloth only, and no wheat. The DC experiences a complete specialisation in the production of cloth. Similarly, the LDC’s pre-trade production and consumption point is N. After trade, its production point shifts to B implying that it specialises in the production of wheat. Thus, trade enables each country to produce more than what it produces domestically.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For simplicity’s sake, we are assuming that the international terms of trade or the post-trade exchange rate is 1W: 1C—an intermediate rate that exists between 2W: 1C and 1W: 2C. To demonstrate this new exchange ratio, we have drawn line TS in Fig. 6. 1(a) whose slope is 1W: 1C (or 1/1). and BD in Fig. 6.1(b)

whose slope is also 1W: 1C (or 1/1). This new terms of trade line enables each country to consume more. Consumption point of DC shifts to point E on the TS line. This means that DC now consumes more of cloth and more of wheat. It exports its surplus cloth production EA to buy AS amount of wheat. Similarly, as a result of trade, LDC’s consumption point shifts to F. This means that it sells its excess production KF amount of wheat to buy KB of cloth from the DC. At point F, LDC consumers, of course, get more of both wheat and cloth.

Thus, trade enables each country to specialise in the production of a commodity in which it has a comparative advantage. Further, trade enables each partner to consume more.

Remember that Ricardo did not specify the exact terms of trade at which trade would take place. His terms of trade ratio lies between the two domestic terms of trade ratios. The exact ratio that would govern trade was left undetermined.

Limitations:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This theory has been criticised on many grounds.

Important criticisms against this theory are:

(i) Unrealistic Assumption of Labour Theory of Value:

Firstly, one of the fundamental assumptions of the classical trade theory is the labour theory of value. This theory states that the relative’ costs of production are determined by the labour costs alone. Their assumption of the labour theory of value seems to be unrealistic in explaining the cause of trade. Modem economists have discarded the labour theory of value and employed opportunity cost theory. Opportunity cost theory rescues Ricardo’s doctrine without altering its basic conclusion.

(ii) Assumption of Perfect Competition Does not Hold:

Secondly, this theory also assumes that there shall be perfect competition. But there are many examples of ‘market failures’. Thus, inefficiencies emerge. Under the circumstance, trade may push a country below the production possibility curve. R A. Samuelson and W. D. Nordhaus then doubt over the conclusion of the comparative cost doctrines. When depressionary condition in an economy prevails or when the price system malfunctions because of environ-mental or other reasons, we cannot be sure that countries will gain from trade.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) Differences in Comparative Costs not Explained:

Thirdly, Ricardo could not explain why do comparative costs differ between countries. Answer to this question was given by Eli F. Heckscher and B. Ohlin who suggested that differences in factor endowments and factor-intensity give rise to differences in comparative costs.

Let us assume that country A uses more capital in the production of a commodity than country B. If the use of capital per unit of labour in country A is higher, then country A is a capital-abundant country. On the other hand, let us assume that the country B is a labour rich country. In our example, we have seen that country A specialises in the production of Y as it has comparative advantage in Y-production. Since country A is a capital- intensive country, Y-production here becomes more capital-intensive.

Likewise, country B has comparative advantage in the production of X. Being a labour-rich country, country B’s production of X becomes more labour-intensive. Heckscher and Ohlin argue that a country will specialise in the production and export those goods whose production requires a relatively large amount of the factor in which the country is relatively well- endowed (i.e., the more abundant factor). Country A—the capital-rich country in this example— specialises in the production of Y (comparative costs of Y are cheaper).

Since country B is a labour-abundant country, its comparative costs are lower in X-production and, hence, it exports X for Y. Thus, differences in factor endowments and factor intensity explain differences in comparative cost. Ricardo simply took for granted that labour cost ratios differ.

(iv) Exact Terms of Trade Undetermined:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Fourthly, Ricardo could not determine the exact terms of trade or the exchange rate at which trade takes place. Ricardo’s terms of trade (TOT) would lie between the countries’ pre-trade terms of trade; but the exact ratio was left undetermined. This gap was filled by the classical author J. S. Mill by introducing the concept of ‘reciprocal demand’ in trade theory. Ricardo’s model concentrates on the supply (or cost) side and, hence, it neglects the demand side.

(v) Zero Transport Cost is Inconceivable:

Fifthly, Ricardo neglects transport cost just for simplicity. It is true that transport costs are important in determining the exchange rate. Supporters of Ricardo’s doctrine have adequately demonstrated that transport costs do not affect comparative cost doctrine.

Trade is multi-lateral and multi-good: Sixthly, for simplicity’s sake, Ricardo’s model is the 2 x 2 X 1 model. But if we apply Ricardo’s theory in case of more than two countries and more than two commodities, conclusions of the doctrine remain virtually unaltered.

(vi) Environmental Argument Against Comparative Cost Theory:

Finally, the assault against the comparative advantage theory in recent times has come from environmentalists. These people argue that in the name of free trade many companies, particularly MNCs, destroy natural resources of a country where they produce. Further, these companies often dump their pollutants in oceans or dump their banned products in the market of developing countries. In the eyes of the environmentalists, trade needs to be restricted so that the harmful effects arising out of trade in harmful environmental products can be minimised.

Extending Ricardo’s Doctrine: (i) Many Commodities but Two Countries:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ricardo’s doctrine has been criticised on the ground that the doctrine is confined only to two commodities and two countries. Critics argue that the doctrine has limited applicability since today’s trade is multilateral. Further, the number of traded goods is not two but many. But Ricardo’s disciples have successfully demonstrated that comparative cost doctrine can even be applied in the case of more than two commodities and more than two countries. Let us see how trade takes place when the two countries trade with more than two goods.

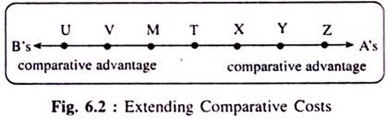

For simplicity’s sake, let us assume that there are two countries A and B who trade seven commodities. These commodities have been arranged in a comparative advantage sequence. Country A has the tendency to specialise in commodities shown on the right hand side of Fig. 6.2.

Similarly, country B has the greatest comparative advantage in U, its advantage in Y or Z is not so large. If now trade opens up, B will export larger U and A larger Z. But what about other goods?

Whether a country will export more of other commodities depends on the strength of the international demand and the TOT. If Y is demanded more by country B, then country A would specialise in its production and produce less in which it has a comparative disadvantage, say good V. Thus, comparative cost is again the basis of trade in the case of many commodities.

Extending Ricardo’s Doctrine: (ii) Many Countries but Two Commodities:

The comparative cost doctrine is equally applicable in a multi-country model. Suppose, there are four countries A, B, C, D who trade with two goods X and Y. For simplicity’s sake. Jet B, C, and D be described as a single group of countries. Thus, for convenience, we have two countries— A and the rest of the world who trade goods X and Y on the basis of comparative cost differences. This assumption makes this extended Ricardian model into a 2 x 2 x 1 model.

Extending Ricardo’s Doctrine: (iii) Multi-countries, Multi-Commodities:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

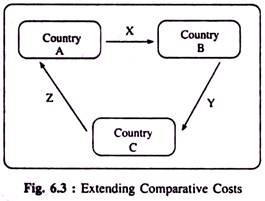

Ricardo’s doctrine has also an applicability in a multi-country, multi-commodity framework. Let there be three countries—both LDCs and developed countries—A, B and C that exchange goods X,’Y and Z with each other Country A exports X to country B, country B exports Y to country C, and country C exports Z to country A. The arrowheads in Fig. 6.3 suggest that trade is a one-way traffic.

This means that no country exports to another country. But it is not so since export of one country is the import of another country. What is true is that country B pays A for its export good X in country C, country C pays B via country A, and so on. Thus, trade takes place between many countries and many commodities. One must not forget that in reality trade patterns are more complex that what has been presented here.