In this article we will discuss about the classical theory of international trade and trade theory applicable to less developed countries.

Classical Theory of International Trade:

The classical comparative costs theory rests upon a series of over-simplifying assumptions such as full employment, fixed supply of factors, constancy of tastes, fixed techniques of production, absence of state intervention, perfectly competitive market conditions, perfect factor mobility internally and perfect factor immobility internationally, balance of trade and the flow of gains from trade to the nationals of a country.

These assumptions do not apply to the conditions of less developed countries, as is evident from the following discussion:

(i) Full Employment:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The classical assumption of full employment of resources is completely invalid in the conditions of less developed countries on account of the fact that there is the existence of vast involuntary unemployment, disguised unemployment, seasonal, technical and structural unemployment. Given the assumption of full employment, the comparative costs theory suggests that specialisation in production and exports results only in the reallocation of productive resources.

The resources are withdrawn from the production of importable goods and are employed in raising the production of exportable goods. In case of the less developed countries, where the resources lie idle or under-utilised, there is not only diversion of resources to the export sector, but the additional inputs have also to be employed to step up production of the primary goods. That creates excess production, lower export prices and consequent instability in exports and adverse terms of trade.

(ii) Fixity of Factor Supply:

The comparative costs theory assumes that the supply of factors of production in a country is fixed. The given factor endowments influence the specialisation of a country. Such an assumption is invalid both in the advanced and less developed counties. In case of the latter, there is expansion of productive resources both in quantitative and qualitative terms. It calls for changes in the specialisation in production and export causing complexity in the applicability of the principle of comparative advantage. However, incapacity of the less developed countries to diversify their production and exports and their limited competitive power leaves them in a state of persistent comparative disadvantage vis-a-vis advanced countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) No State Intervention:

The classical principle of comparative advantage rests upon the assumption that there should be no interference from the state in the field of production and international trade. It was believed that the optimum international exchange could be possible only if there is unrestricted flow of goods dictated purely by the comparative differences in costs.

The experience of less developed countries demonstrates amply that free trade leads to cut-throat competition, dumping and depreciation of currencies. The free trade makes the poor countries poorer and the advanced countries more prosperous.

In order to protect their interests in the matters of trade and development, they have to rely upon tariffs, import quotas, export subsidies, foreign exchange restrictions and state trading. Even the advanced countries have been following more and more protectionist policies in spite of their professions about free trade. In such conditions, the less developed countries cannot follow the principle of comparative costs advantage.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iv) Perfectly Competitive Market Conditions:

The comparative costs theory assumes that there are conditions of perfect competition in the market. This assumption is completely invalid. The monopolistic and oligopolistic industrial and commercial enterprises dominate the international market. The less developed counties have underdeveloped infrastructure and institutions. Their economies have extreme dependence on primary production.

They are not well-equipped to face competition from powerful foreign cartels and multinational corporations (MNC’s), which manipulate world demand, factor supplies and prices to their own advantage. In such conditions, the adherence to the classical principle of comparative cost advantage by the less developed countries is unimaginable.

(v) Factor Mobility:

The classical writers built up the entire structure of comparative costs principle on the assumption that there is perfect mobility of factors within a country but there is perfect immobility of factors internationally. This assumption is not valid in the less developed counties. There are serious obstacles even to the internal mobility of labour and capital owing to institutional and structural rigidities. On the other hand, there are international flows of labour, technology and capital between the rich and the poor countries.

(vi) Constancy of Tastes or Preferences:

The comparative costs theory assumes that tastes or preferences of the people remain unchanged in the trading countries. This assumption is completely unrealistic. In the less developed countries, changes in the system of preferences continue to take place due to changes in income, changes in the composition of output, demonstration effect of superior consumption standards in advanced countries and powerful advertising campaigns started by the domestic producers and MNC’s.

(vii) Fixed Techniques of Production:

The principle of comparative costs also rests upon the assumption that the techniques of production remain fixed. Such an assumption is not true either in an advanced or a less developed country. There has been continuing research in scientific, industrial and technical fields. Even the less developed counties have been absorbing, though to a limited extent, new technical inventions and innovations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such technical changes have made a significant impact upon both the patterns of exports and imports. In the case of India, for instance, her exports presently include such items as iron and steel products, engineering and electronic goods, computer softwares, transport equipments and machine tools apart from the traditional exports of textiles and primary products.

Similarly, the imports not only include manufactured consumer goods but also industrial raw materials, intermediate products, machinery and equipment and advanced technical know-how. India also possesses a fairly developed infra-structure for furthering industrial, agricultural and scientific research. In such conditions of dynamic technical changes, the comparative costs theory does not apply.

(viii) Balance of Payments Deficit:

The comparative costs theory maintains that the flow of goods between two trading counties is fully matched. As a result, there is always a state of equilibrium in respect of balance of trade and payments, assuming an absence of capital movements. There is absolutely no basis for holding such a notion. The less developed countries are faced with serious balance of payments deficits and acute foreign exchange shortages that have landed them in a deep crisis of international debt trap.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ix) Gains from International Trade:

The classical trade theory states that the gains from international trade accrue to the nationals of trading countries. In case of most of the less developed countries, this has not materialised. The foreign investors still own mines and plantations in these countries. They acquire lands on low rents, exploit cheap labour, and pocket a substantial part of the export earnings of these countries.

The MNC’s receive concessions from the governments of less developed countries in the form of tax holidays, development rebates, depreciation allowances, exports privileges and facilities for the repatriation of capital and remittances of profits. The flow of gains to the nationals of the poor countries is not at all commensurate with their efforts to increase exports.

It is now obvious that the classical principle of comparative cost advantage has little relevance to the conditions of less developed countries. It is important for these countries, at least in the early stage of their development, to pursue protectionist policies to develop and diversify the industries rather than to allow the unrestricted flow of cheap products to flood their markets and disorganise completely their whole structure of production.

Trade Theory Applicable to Less Developed Countries:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

During the 1950’s and 1960’s, the trade specialization based on the classical principle of comparative cost advantage came under attack from the writers including Singer (1950), Myrdal (1957), J. Bhagwati (1958), Chenery (1961), Balogh (1963), Prebisch (1964), Nurkse (1967) and Wilson (1969).

These writers suggested that the traditional theoretical analysis was inappropriate to tackle the problems faced by the less developed countries in respect of trade and development. Hla Myint has, however, attempted to explain that certain elements in Adam Smith’s line of approach that were neglected by these critics, could be fruitfully developed to analyse the past and present patterns of trade in the less developed countries.

These neglected elements of classical theory were:

(i) Productivity doctrine, and

(ii) Vent for surplus theory of Adam Smith.

(i) Productivity Doctrine:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Adam Smith’s productively doctrine does not have a classical static bias. It views international trade as a dynamic force that widens the size of market; expands the scope of division of labour; raises the skill and dexterity of workers; induces technical inventions and innovations; overcomes technical indivisibilities; ensures an improvement in the factor productivity; and enables a country to enjoy increasing returns- and consequent greater economic development.

The line of approach in this doctrine is clearly different from the comparative costs theory of specialisation, which had envisaged movement along a static production possibility curve based on the assumption of given resources and techniques of production.

The comparative costs principle states that the specialisation involves the reallocation of resources. It implies that specialisation is a completely reversible process. The productivity doctrine, on the opposite, involves a complete restructuring of the process of production to meet the export demand.

In such an event, the specialisation cannot be easily reversible. It recognizes that a country specialising for the export market is more vulnerable to change in the terms of trade. This doctrine, therefore, anticipated the view expressed by Prebisch ad Singer that there has been secular deterioration of terms of trade for the less developed countries.

Myint pointed out that the vulnerability aspect of international specialisation remained subordinated to the productivity aspect during the nineteenth country. In the less developed countries, Smith’s productivity doctrine got developed into an export- drive argument and it even overcame the free-trade argument. It was realised that since international trade was so beneficial in raising productivity and stimulating development, the state should not remain a passive spectator.

It should adopt more positive policies to encourage exports through export subsidies, tax concessions and encouragement even to monopolistic practices for expanding exports. These measures, amounting to abandonment of laissez faire, resulted in a rapid increase in the value and physical volume of exports so much so that the growth rate of exports even outstripped the growth rate of population and consequent increase in the output per capita.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this connection, it must be acknowledged that the increase in per head production in the 19th century did not proceed in the way analyzed by Adam Smith, viz., a better division of labour and specialization leading on to innovation and cumulative improvement in skills.

The increase in per head productivity in the 19th century occurred, in fact, because of:

(i) Transfer of labour from the subsistence economy to the mines and plantations;

(ii) An increase in working hours; and

(iii) An increase in the proportion of gainfully employed labour relatively to the under-employed labour.

In the words of Hla Myint, “Thus instead of a process of economic growth based on continuous improvement in skills, more productive recombinations of factors and increasing returns, the nineteenth century expansion of international trade in the underdeveloped countries seems to approximate to a simpler process based on the constant returns and fairly rigid combinations of factors. Such a process of expansion could continue smoothly only if it could feed on additional supplies of factors in the required proportions.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) The Vent for Surplus Theory:

The vent for surplus approach of Adam Smith can be traced back to strong export bias of the Mercantilist economists. The theory maintains that an underdeveloped country may have, in the absence of international trade, a surplus domestic productive capacity on account of its unutilised or underutilised natural resources, labour resources and small extent of domestic market.

It is true that the country can absorb its surplus production domestically but it may involve serious price and income decline. In addition the process of absorption may be slow. Till the surplus of production is fully absorbed, there may be little inducement to expand investment and production and the country may remain in a state of long term stagnation and poverty.

The international trade can absorb this surplus of production without creating unsettling effects upon the poor countries. The export of surplus product will create new effective demand for the products of the less developed countries and it does not involve any reduction in domestic availability of goods.

In this connection, Adam Smith remarked, “When the produce of any particular branch of industry exceeds what the demand of the country requires, the surplus must be sent abroad, and exchanged for something for which there is a demand at home. Without exportation, a part of the productive labour of the country must cease, and the value of its annual produce diminishes.”

The international trade absorbs the surplus domestic production and prevents any likely slump in the home market, creates markets for products abroad; and permits the import of more essential and scarce materials, manufactured consumer and producer goods from the foreign countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this way, the vent for surplus doctrine emphasises that international trade cannot be an obstacle but an opportunity for accelerating the process of growth. Myint, therefore, considered the vent for surplus doctrine of Adam Smith as more appropriate for the less developed countries than the principle of comparative cost advantage.

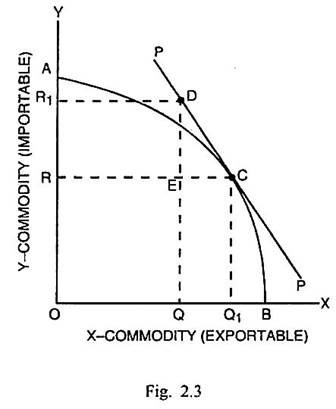

The gain for a less developed country from international trade can be shown through Fig. 2.3. It is supposed that before trade a poor country has surplus productive capacity in the form of underutilised natural resources and manpower. The domestic demand for the product being deficient, there is some surplus of production. If this surplus is exported, it can permit some quantity of foreign products to be imported resulting in a higher level of aggregate satisfaction.

In Fig. 2.3, AB is the production possibility curve, which indicates the maximum production potential of the country related to X and Y commodities, given the techniques of production and fullest utilization of all productive resources. Before trade, this country produces OQ of X and OR of Y and there is the presence of surplus productive capacity. If there is fullest utilization of resources, the domestic production of X commodity at C is OQ1 along with OR of Y.

The domestic demand for X is limited only upto OQ because of limited extent of market. There is surplus production amounting to QQ1 of X. If this surplus is exported to foreign countries, given the international exchange ratio line PP, this country can import DE or RR1 quantity of Y in exchange to QQ1 of X. It will signify an improvement in consumption standard or an increase in welfare. Thus the export of surplus product can promote prosperity of a less developed country.

Appropriateness of the Vent for Surplus Theory:

Hla Myint stressed that the vent for surplus theory of Adam Smith was more appropriate for the less developed countries compared with the comparative cost doctrine.

He has made the following main points in this regard:

(i) Existence of Surplus Productive Capacity:

The comparative costs theory is not relevant to the LDC’s because it assumes given techniques and full employment of resources. In the LDC’s, the unutilised and under-utilised resources exist in a large measure. In such conditions, the production can be increased through greater use of resources than by mere reallocation of resources as suggested by the principle of comparative costs.

The surplus production, resulting from discovery of mineral resources, increase in area under cultivation, improvement in techniques and extension of means of transport and communications, can be economically utilised through its exports to foreign countries.

(ii) Limited Size of Domestic Market:

The LDC’s remain in a state of poverty because of small size of internal market. It has a prohibitive effect on investment and production. The comparative costs doctrine stressed only upon cost differences and overlooked this important aspect. The disposal of surplus produce in the foreign countries can open up new markets for products and ensure more opportunities of investment, production and employment and the LDC’s can expand their production frontiers.

(iii) Quantitative Differences in Resources:

The comparative costs theory maintains that trade between the temperate advanced counties and tropical LDC’s has grown out of the cost differences caused by the climatic and geographical differences and the qualitative differences in factors. It tends to overlook the quantitative differences in resource endowments of the countries possessing approximately the same type of climate and geography. The vent for surplus approach which directs our attention towards quantitative differences in endowments of factors seems to have an advantage over the conventional theory.

(iv) Mobility of Labour and Specificity of Factors:

The comparative costs theory assumes perfect internal mobility of labour and possibility of change in factor specialization. In the LDC’s there are serious impediments upon the internal mobility of labour and the factors of production are very product-specific. It is difficult to absorb any surplus of production without substantial decline in prices. The vent-for-surplus approach shows a way to get out of such a predicament and, therefore, has much relevance to the conditions of LDC’s.

(v) Developed and Flexible Economic System:

The comparative costs theory assumes that a country entering into international trade possesses a highly developed and flexible economic and institutional framework capable of making easy and quick adjustments in methods of production and combinations of factors. In LDC’s, on the contrary, there are rigidities in the economic and institutional structures. A crude and straight forward approach like the vent-for-surplus is clearly more suited to the conditions of these countries.

(vi) Policy Implication:

The comparative costs theory emphasised upon the policy of laissez faire and free trade that has resulted in serious exploitation of the economies of the LDC’s. The vent-for- surplus approach, on the other hand, permits the monetary and fiscal authorities to adopt measures suitable for the expansion of exports. This approach seems to be more consistent with the modern realities.

The above arguments suggest that the approach of Adam Smith based on productivity and vent-for- surplus doctrine is more effective than the traditional comparative costs theory. But even this approach cannot provide an exact fit to all the patterns of development in different types of export economics. No simple theoretical approach is likely to do so. It has to be properly qualified to become applicable to the conditions existing in a given economic system.