In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Meaning of Political Market 2. Concept of Median Voter 3. Lobbying 4. The Choice of Protective Instruments 5. Anti-Dumping Legislation 6. Rent-Seeking 7. Empirical Work.

Meaning of Political Market:

In the latter half of 1950’s, the political scientists and economists like Becker. Buchanan, Tullock, Downs, Olson and Stigler developed the model called as the political market model of protection. This model recognises that the demand for the policy of protection comes from the individuals as consumers or from the organised groups like producers, labour union, share owners etc. The demand for increased protection or the opposition to its reduction is made by those who are likely to be benefitted by such measures.

The supply of protection-related policies comes from elected legislators, heads of government and bureaucrats. The politicians either offer or maintain these policies with the object of maximising their prospects at the ballot box for getting elected or to get re-elected, if already in office.

The behavior or response of politicians to the demand for protection is guided by the voting system, the intensity of preferences of different groups for potential policy changes, the ability of voters’ groups to deliver their votes and their contributions to campaign funds.

Concept of Median Voter:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The equilibrium in the political market will produce such a policy that may provide gain for the majority and loss for a small minority. Suppose there are two competing political parties, each one of them is willing to promise such tariff rates that can enable it to win the next election. The voters are likely to be divided in their preferences about the policy. It is further supposed that the country exports skill-intensive goods and imports labour- intensive goods.

The low tariff rates will be favoured by the voters with high skill levels, whereas high tariff rates will be preferred by the voters with low skill levels. Now the crucial question is what policies the two parties will promise to follow. Both will tend to find the middle ground. They will have a tendency to converge on such a tariff rate that is preferred by the median voter.

The median voter may be defined as a voter who is exactly half way in the line-up of voters. On one side of the median voter will be the voters who prefer high tariff rates and on the other side of him are those who prefer lower tariff rates. According to Soderston, the median voter is one who turns a minority into the majority.

In employing the median voter model for providing explanation for the existence of protective tariff in a democracy and for the pressure to increase tariff rates than to reduce it, Robert Baldwin suggested that certain points should be kept into consideration. First, the reduction in tariff rates will cause losses to producers of import-competing goods and owners of factors specific to those goods.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, they may form a group able to command a stable majority in the parliament. It will result in higher tariffs as the favoured policy. Second, the beneficiaries from tariff reduction such as households, firms in export industries and firms using imported goods as inputs may be spread over a large group; may be uncertain of size and timing of their gains; may have smaller gain individually; and may be more difficult to organise. The losers from tariff reduction may be, on the other hand, less numerous.

They may expect a greater loss individually. They may be more certain about the size and timing of their losses. They may either be already organized or may be easier to organise. The losers are likely to be more willing to vote or lobby for increase in tariff rates. Third, as compared to the prospective gainers from tariff reduction, the prospective losers may be better represented in the parliament on account of their geographical distribution across the electoral districts.

Suppose there are three districts of equal size. The prospective losers have a bare majority in two of them and no member in the third. Those elected carry out the wishes of the majority of their own electorate, then the potential losers will have a majority in the parliament, even though they constitute only 33 percent of the voters. Fourth, vote trading, i.e., agreement among two of the three districts to vote in favour of the other, can affect the outcome of the majority voting.

Fifth, in the LDCs where tax system is inefficient and tariff revenue constitutes a substantial proportion of government revenue and there are few alternative sources of revenues, the possibility of generating additional revenues through tariff can be a relevant consideration in affecting the decision.

Lobbying:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If the government attempts to effect reallocation of income after a change in tariff policy openly, it may be politically dangerous. The government may decide to constitute a board or commission of experts to carry out the costs and benefits analysis of any change. The different pressure groups will start the lobbying activity to make the experts either to change or maintain the status quo.

The extent and effectiveness of lobbying activity by them is an important element in the political market for protection. In this connection, Bruno Frey developed a model of optimal amount of lobbying in 1985.

The lobbying activity, on the one hand, assures benefit to pressure groups in the form of addition to producer surplus due to increase in tariff rate from the present level. The gain in producer surplus will be available at the decreasing rate with the increase in tariff rate until trade is eliminated. On the other hand, lobbying activity involves costs such as costs of organising the lobbying group, of employing the lobbying agents and cost of overcoming opposition to the increase in tariff.

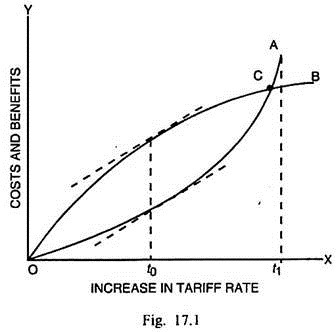

The addition to lobbying cost tends to increase at the increasing rate as the rate of tariff increases. The optimum tariff rate can be shown through Fig. 17.1.

In Fig. 17.1, the increase in tariff rate is measured along the horizontal scale. Costs and benefits are measured along the vertical scale. OA is the cost of lobbying curve. The slope of this curve increases indicating that the marginal cost of lobbying increases with an increase in tariff rate. OB is the benefits curve, the slope of which decreases. It indicates that the marginal benefit from tariff increase diminishes as the rate of tariff increases. The vertical distance between OA and OB curve upto the intersection point C measures the net gain from lobbying.

At the intersection point C, the net gain from lobbying is zero. t1 is the prohibitive rate of tariff, which may possibly eliminate the trade. The tariff rate is optimum where the net gain from lobbying is maximum or where marginal cost of lobbying becomes equal to the marginal benefit from it. When tariff increase takes place at the rate the slopes of OA and OB curves become exactly equal as the tangents drawn to these two curves become parallel to each other. Thus, t0 is the optimum rate of tariff increase.

The Choice of Protective Instruments:

Tariff is not the only protective instrument, there are alternative protective instruments such as quantitative restrictions which may be preferred by both producers and government. The producers may have a preference for quotas because of greater certainly in their effects. The reasons why the governments may prefer the quantitative restrictions is that their effects are not readily apparent to the consumers.

In a small country; a tariff of 15 percent will raise the home prices by 15 percent and consumers are aware that like other indirect taxes, the given price rise is due to tariff. The quantitative restrictions to raise prices but the consumers will not be aware of that. From the point of view of the government, it will be more prudent to adopt quantitative restrictions than tariff as the former are less likely to provoke adverse reactions from the consumers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The government may even prefer the voluntary export restrictions to import quotas because the latter are not approved by WTO rules and the other countries are likely to raise protests against them. In case of voluntary export restraints, the protests from foreign countries can be stifled by offering an incentive to foreign exporters by allowing them to capture the rents generated by those restraints and also by allowing them a guaranteed market over the period of agreement.

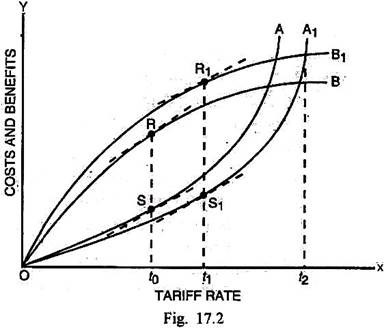

The choice between the quantitative restriction and equivalent tariff can be discussed through Fig. 17.2.

In Fig. 17.2., OB is the benefit curve corresponding to different rates of tariff. The cost of lobbying curve in the case of tariff option is OA. The tariff rate corresponding to the optimum lobbying is t0. The net benefit to the lobbyists is RS, which is maximum. If the producers’ preferences are for quantitative restriction, the benefit curve will be higher at the level of OB1 than OB.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The government’s preference for quantitative restriction or VER is reflected by the lower cost of lobbying curve OA1. The net benefit in the case of quantitative restriction is maximum at R1S1 with the equivalent tariff rate t1. The tariff rate t2 equivalent quantitative restrictions) indicates the prohibitive tariff at which the imports get eliminated.

From the Fig. given above, it becomes clear that the optimum lobbying for quantitative restriction affords not only greater protection but also greater benefits for the lobbyist than the optimum lobbying for the tariff.

Anti-Dumping Legislation:

The WTO agreement permits the governments to take discriminatory action such as the imposition of countervailing duties against the goods that are dumped by a particular country. The country adopting the anti-dumping action is required to establish that the dumping is taking place. It has to calculate the extent or margin of dumping. It has also to show that the dumping has been causing injury to the industry in the home country.

Under the WTO agreement, the anti-dumping action cannot apply if the margin of dumping is insignificantly small, i.e., less than 2 percent of the export price or the volume of imports is negligible i.e., the imports from the offending country are less than 3 percent of the total import of that product. When a country decides to impose the countervailing duties, it is important, that such duties should not be more than the margin of dumping.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Dumping is supposed to have occurred when the price of product exported by the offending country is lower than its normal value. The difference between the export price and normal value measures the extent or margin of dumping.

The dumping procedure is identified by the domestic firms, which initially make the complaint that the foreign country has been causing injury to them. In this regard, they put forward the evidence that the import of low-period goods has reduced the sales of their companies or that the imports have reduced their market share, or that the volume of such imports has been swelling. In case, the domestic firms are able to persuade the authorities in home country to recognise the validity of their claim, the ground is paved for the clamping of antidumping legislation.

Between 1980 and 1986, the United States and European Union were found to be most active in invoking the anti-dumping legislation against the foreign exporters. They were also most subjected to similar action by the other countries.

Australia and Canada, on the other hand, were the countries, which initiated the anti-dumping action against many countries but they were subjected to such action by very few countries. Japan during the same period, faced anti-dumping action from many countries but that country did not invoke such legislation against any country.

Rent-Seeking:

Rent-seeking can be defined as the seeking of rent from the quantitative restriction enforced by a country on imports. This phenomenon was first identified by A.O. Krueger in 1974. According to him, if the quota is allocated by the authorities through the import licences, then each licence carries with it an element of rent. The import licences, in such a situation, become a valuable asset and there will be competition among the firms to secure a licence.

Jagdish Bhagwati defined the rent-seeking activity as “ways of making profits (i.e., income) by undertaking activities that are directly unproductive; that is, they yield pecuniary returns but produce neither good nor services that enter a conventional utility function directly nor intermediate inputs into such goods and services.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The competition among the firms to secure import licence involves similar type of lobbying as in case of tariff rates. There is the use of scarce resources in such an activity. The firms make use of resources for the acquisition of an asset rather than the production of a marketable good or service. Consequently, the welfare of the community will get reduced.

In his analysis related to rent-seeking, Krueger considers a small country specialising in the production of food and import of manufactured goods. Apart from the production costs, there is inclusion of internal distribution costs in the costs. The import licences are allocated to the distributors.

The people working in the distribution sector are able to secure rents from quantitative restrictions on imports. According to Krueger, people will continue to enter the distribution sector until the average wage including rent in the distribution sector becomes equal to the average wage in the food sector.

On the basis of this analysis, Krueger could make a number of conclusions:

(i) The welfare cost of import quota is equal to the welfare cost of equivalent tariff plus the additional cost of rent-seeking activity. It implies that ranks to two or more quotas cannot be assigned on the basis of their equivalent tariffs.

(ii) In the case of tariff or import quota without rent-seeking, the dead-weight loss is likely to be smaller, when the domestic demand is relatively less elastic. In case the quantitative restriction is considered along with rent-seeking, the dead-weight loss is likely to be greater.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) If there is competition for import licences under quotas, an import prohibition is preferable to non-prohibitive quota because in case of the former, there will not be rent-seeking. No doubt, the possibility of smuggling of the product will exist in such a situation.

(iv) The government has to face a dilemma whether to issue licence to one importer thereby creating monopoly or to permit competition and disperse widely the rent-seeking. If import licence is issued to one importer (or a small group of importers), the government will be charged with favouritism. On the other hand, if it permits competition for import licences, there will not be charge of favouritism. At the same time, there will be a wider distribution of income. The cost of quantitative restrictions to the economy, however, will increase considerably.

(v) The rent-seeking activity is sometimes seen as a policy rewarding the rich and well- connected people. It tends to weaken the belief of the people in market system. It leads to an increase in the pressure upon government for more direct intervention which may reduce economic efficiency, on the one hand, and increased activity directed towards rent-seeking, on the other.

According to Krueger, the total amounts of rent secured in India in 1964 were about 7.3 percent of national income. The rents from imports licences alone in Turkey in 1968 were of the magnitude of 15 percent of the GNP of that country.

Empirical Work on the Political Economy of Protection:

The empirical work related to the political economy of protection can be put into three categories:

(i) Detailed study of voting pattern of the members of Parliament on trade-related issues,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Statistical estimation of impact of various economic and political variables upon the observed pattern of protection across economic activities within a country,

(iii) Pattern of negotiations on tariff reductions under the GATT.

(i) Voting Pattern of Elected Representatives on Trade Related Issues:

About the voting pattern of U.S. Congressmen on the trade-related issues, a prominent study was attempted by R.E. Baldwin in 1976. He pointed out that the Congressmen had a tendency to vote in favour of protective measures. This was on account of two factors. Firstly, there were a high proportion of import-competing industries in their constituencies. Secondly, three major trade unions had made contributions to the campaign funds of a Congressman supporting protection.

In another study made by R.E. Baldwin, the voting pattern was analyzed on the U.S. Trade Bill of 1973. According to him, the Democrats in both Senate and House of Representatives were significantly more protectionist than the Republicans, and the protectionist trade union contributions were primarily given to those who voted against the Act.

It was also found by Baldwin that Congress and the President were both more inclined to adopt protectionist legislation just before the election.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Statistical Estimation of Impact of Economic and Political Variables:

In regard to the estimation of impact of economic and political variables upon the observed pattern of protection across the economic activities, the earliest study was attempted by R.E. Caves. He tested in 1963 three models on nominal and effective protection in Canada. The first of these models was termed as the ‘adding machine’ model.

According to it, the policy makers had the assumed aim of maximising the benefit to the greatest possible number of votes. The second model, termed as interest group model, explained the influence of lobbying activity. The third model was termed as ‘national interest’ model, according to which infant industry protection was given to the sectors where it was likely to be most effective.

According to Caves, such industries were those that offered high wages and showed rapid and balanced growth. Caves could find little evidence for the adding machine model. There was only weak evidence for the national interest model. The interest group model, in contrast, performed reasonably well. It could explain about half of the variations in tariff rates between different industries.

A study was made by E.J. Ray about the tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade in the United States and some other countries in 1981. The U.S. tariffs were found to be related positively to the degree of concentration and labour-intensity of industry. They were related negatively to the intensity of skilled labour.

Since lobbying is more-easy to organise in a concentrated industry, the positive relationship between degree of concentration and tariffs is consistent with the lobbying hypothesis. The role of labour-intensity was found to be consistent with the H.O. model and also with the voting power of labour. He also found consistency of negative effect of tariffs on skilled labour with the H.O. model. It indicated also a greater degree of political activity on the part of skilled labour.

According to E.J. Ray, the non-tariff barriers in the United States appeared complementary to tariffs. The former were found to be relatively more important in those industries, which were intensive in physical capital and produced non-differentiated products. It led to the suggestion that the U.S.A. was perhaps so uncompetitive in such industries that given low tariff rates, sufficient protection could be afforded only through non-tariff restrictions.

The evidence was also found that the use of non- tariff barriers by the United States was in retaliation to their use by foreign countries. From his study related to the protection in seven major competitors to the United States, Ray found that skilled labour cost due to tariff structure in these countries reflected the relative importance of skilled labour in their export-industries.

The inter-industry pattern of protection in Britain was studied by Greenaway and Milner in 1990. They attempted to specify the target level of protection of each industry that might assume the form of tariff and non-tariff barriers. According to them, certain factors like the concentration of market power, the degree of unionisation and geographical concentration, make it easier to organise lobbying.

Other relevant factors in this regard are the range of products, share of sales going to other industries and the level of employment. In case the range of products is narrow, a specialised industry can better concentrate its lobbying efforts. They could find no support for the product and labour market power hypothesis. Only a limited support could be found for the geographical and product specialisation hypothesis. However, they did find significant support for the countervailing power hypothesis.

The pressure for protection seemed to increase and inducement for higher nominal tariff increased, when there were high import share, greater wage cost or labour intensity and greater intensity of unskilled labour. The comparative advantage and adjustment cost influences were also the relevant considerations. The structure of tariff bargained for the future was found to be influenced by the adjustment pressure and the political economy.

Greenaway and Milner recognised that the results suggested that there were current endogenous and political economy influences on the target rate of nominal protection in Britain.

In the case of effective tariff, Greenaway and Milner pointed out that the results were broadly similar, except that the countervailing power hypothesis, which appeared to hold in the case of nominal tariff, did not seem to hold in case of the setting of effective tariff target.

Like other developed market economies, Britain had also placed greater reliance since the mid-1970’s upon non-tariff barriers like quota, subsidies, voluntary export restraints and other source-specific measures. Greenaway and Milner found that tariff and non-tariff barriers might be complements rather than substitutes in that country.

(iii) Pattern of Negotiations on Tariff Reduction under GATT:

The pattern of negotiations on tariff reduction at GATT was studied by J. Cheh in 1974. About the concessions made by the United States concerning tariff reduction in the Kennedy Round of GATT, he found that exceptions seemed to be made for such industries as were labour- intensive; were slow growing or declining and; were geographically concentrated, excluding certain strategic goods and those like textiles, where GATT escape clauses were already in operation.

The study made by Cheh led to the conclusion that the avoidance of short-term labour adjustment cost was the essential aim of making these exceptions. A similar study was attempted by J. Riedel in 1977 for West Germany. In respect of nominal tariff, he could find no support for Cheh’s conclusions. But he arrived at similar results in respect of effective protection.