The following points highlight the top three theories of investment in Macro Economics. The theories are: 1. The Accelerator Theory of Investment 2. The Internal Funds Theory of Investment 3. The Neoclassical Theory of Investment.

Theory of Investment # 1. The Accelerator Theory of Investment:

The accelerator theory of investment, in its simplest form, is based upon the nation that a particular amount of capital stock is necessary to produce a given output.

For example, a capital stock of Rs. 400 billion may be required to produce Rs. 100 billion of output. This implies a fixed relationship between the capital stock and output.

Thus, X = Kt /Yt

ADVERTISEMENTS:

where x is the ratio of Kt, the economy’s capital stock in time period t, to Yt, its output in lime period t. The relationship may also be written as

Kt = xYt …(i)

If X is constant, the same relationship held in the previous period; hence

Kt-1 = xYt-1

ADVERTISEMENTS:

By subtracting equation (ii) from equation (i), we obtain

Kt –Kt-1 = xYt.x Yt-1 = x(Yt-Yt-1) …(ii)

Since net investment equals the difference between the capital stock in time period t and the capital stock in time period t – 1, net investment equals x multiplied by the change in output from time period t – 1 to time period t.

By definition, net investment equals gross investment minus capital consumption allowances or depreciation. If It represents gross investment in time period t and Dt represents depreciation in time period t, net investment in time period t equals It – Dt and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It-Dt = x (Yt – Yt-1) = x ∆ Y.

Consequently, net investment equals x, the accelerator coefficient, multiplied by the change in output. Since x is assumed constant, investment is a function of changes in output. If output increases, net investment is positive. If output increases more rapidly, new investment increases.

From an economic standpoint, the reasoning is straightforward. According to the theory, a particular amount of capital is necessary to produce a given level of output. For example, suppose Rs. 400 billion worth of capital is necessary to produce Rs. 100 billion worth of output. This implies that x, the ratio of the economy’s capital stock to its output, equals 4.

If aggregate demand is Rs. 100 billion and the capital stock is Rs. 400 billion, output is Rs. 100 billion. So long as aggregate demand remains at the Rs. 100 billion level, net investment will be zero, since there is no incentive for firms to add to their productive capacity. Gross investment, however, will be positive, since firms must replace plant and equipment that is deteriorating.

Suppose aggregate demand increases to Rs. 105 billion. If output is to increase to the Rs. 105 billion level, the economy’s capital stock must increase to the Rs. 420 billion level. This follows from the assumption of a fixed ratio, x, between capital stock and output. Consequently, for production to increase to the Rs. 105 billion level, net investments must equal Rs. 20 billion, the amount necessary to increase the capital stock to the Rs. 420 billion level.

Since x equals 4 and the change in output equals Rs. 5 billion, this amount, Rs. 20 billion, may be obtained directly by multiplying x, the accelerator coefficient, by the change in output. Had the increase in output been greater, (net) investment would have been larger, which implies that (net) investment is positively related to changes in output.

In this crude form, the accelerator theory of investment is open to a number of criticisms.

First, the theory explains net but not gross investment. For many purposes, including the determination of the level of aggregate demand, gross investment is the relevant concept.

Second, the theory assumes that a discrepancy between the desired and actual capital stocks is eliminated within a single period. If industries producing capital goods are already operating at full capacity, it may not be possible to eliminate the discrepancy within a single period. In fact, even if the industries are operating at less than full capacity it may be more economical to eliminate the discrepancy gradually.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Third, since the theory assumes no excess capacity, we would not expect it to be valid in recessions, since they are characterized by excess capacity. Based on the theory, net investment is positive when output increases. But if excess capacity exists, we would expect little or no net investment to occur, since net investment is made in order to increase productive capacity.

Fourth, the accelerator theory of investment, or acceleration principle, assumes a fixed ratio between capital and output. This assumption is occasionally justified, but most firms can substitute labor for capital, at least within a limited range. As a consequence, firms must take into consideration other factors, such as the interest rate.

Fifth, even if there is a fixed ratio between capital and output and no excess capacity, firms will invest in new plant and equipment in response to an increase in aggregate demand only if demand is expected to remain at the new, higher level. In other words, if managers expect the increase in demand to be temporary, they may maintain their present levels of output and raise prices (or let their orders pile up) instead of increasing their productive capacity and output through investment in new plant and equipment.

Finally, if and when an expansion of productive capacity appears warranted, the expansion may not be exactly that needed to meet the current increase in demand, but one sufficient to meet the increase in demand over a number of years in the future.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Piecemeal expansion of facilities in response to short-run increases in demand may be uneconomical or, depending upon the industry, even technologically impossible. A steel firm cannot, for example, add half a blast furnace. In view of these and other criticisms of the accelerator theory of investment, it is not surprising that early attempts to verify the theory were unsuccessful.

Over the years, more flexible versions of the accelerator theory of investment have been developed. Unlike the version of the accelerator theory just presented, the more flexible versions assume a discrepancy between the desired and actual capital stocks which is eliminated over a number of periods rather than in a single period. Moreover, it is assumed that the desired capital stock, K*, is determined by long-run considerations. As a consequence

where Kt is the actual capital stock in time period t, Kt-1 is the actual capital stock in time period t-1, Kt* is the desired capital stock, and λ is a constant between 0 and 1. The equation suggests that the actual change in the capital stock from time period t – 1 to time period t equals a fraction of the difference between the desired capital stock in time period t and the actual capital stock in time period t—1. If λ were equal to 1, as assumed in the initial statement of the accelerator theory, the actual capital stock in time period t equals the desired capital stock.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since the change in the capital stock from time period t – 1 to time period t equals net investment, It – Dt we have

Consequently, net investment equals A multiplied by the difference between the desired capital stock in time period t and the actual capital stock in time period t- 1. The relationship, therefore, is in terms of net investment.

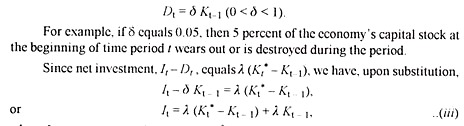

To account for gross investment, it is common to assume that replacement investment is proportional to the actual capital stock. Thus, we assume that replacement investment in lime period t, Dt equals a constant δ multiplied by the capital stock at the end of time period t-1, Kt-1, or

where It represents gross investment, Kt* the desired capital stock, and Kt. , the actual capital stock in time period t-1. Thus, gross investment is a function of the desired and actual capital stocks.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally, according to the accelerator model, the desired capital stock is determined by output. Yet, rather than specifying that the desired capital stock is proportional to a single level of output, the desired capital stock is commonly specified as a function of both current and past output levels. Consequently, the desired capital stock is determined by long-run considerations.

In contrast to the crude accelerator theory, much empirical evidence exists in support of the flexible versions of the accelerator theory.

Theory of Investment # 2. The Internal Funds Theory of Investment:

Under the internal funds theory of investment, the desired capital stock and, hence, investment depends on the level of profits. Several different explanations have been offered. Jan Tinbergen, for example, has argued that realized profits accurately reflect expected profits.

Since investment presumably depends on expected profits, investment is positively related to realized profits. Alternatively, it has been argued that managers have a decided preference for financing investment internally.

Firms may obtain funds for investment purposes from a variety of sources:

(1) Retained earnings,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(2) Depreciation expense (funds set aside as plant and equipment depreciate),

(3) Various types of borrowing, including sale of bonds,

(4) The sale of stock.

Retained earnings and depreciation expense are sources of funds internal to the firm; the other sources are external to the firm. Borrowing commits a firm to a series of fixed payments. Should a recession occur, the firm maybe unable to meet its commitments, forcing it to borrow or sell stock on unfavorable terms or even forcing it into bankruptcy.

Consequently, firms may be reluctant to borrow except under very favourable circumstances.

Similarly, firms may be reluctant to raise funds by issuing new stock. Management, for example, is often concerned about its earnings record on a per share basis. Since an increase in the number of shares outstanding tends to reduce earnings on a per share basis, management may be unwilling to finance investment by selling stock unless the earnings from the project clearly offset the effect of the increase in shares outstanding.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Similarly, management may fear loss of control with the sale of additional stock. For these and other reasons, proponents of the internal funds theory of investment argue that firms strongly prefer to finance investment internally and that the increased availability of internal funds through higher profits generates additional investment. Thus, according to the internal funds theory, investment is determined by profits.

In contrast, investment, according to the accelerator theory, is determined by output. Since the two theories differ with regard to the determinants of investment, they also differ with regard to policy. Suppose policy makers wish to implement programs designed to increase investment.

According to the internal funds theory, policies designed to increase profits directly are likely to be the most effective. These policies include reductions in the corporate income tax rate, allowing firms to depreciate plant and equipment more rapidly, thereby reducing their taxable income, and allowing investment tax credits, a device to reduce firms’ tax liabilities.

On the other hand, increases in government purchases or reductions in personal income tax rates will have no direct effect on profits, hence no direct effect on investment. To the extent that output increases in response to increases in government purchases or tax cuts, profits increase. Consequently, there will be an indirect effect on investment.

In contrast, under the accelerator theory of investment, policies designed to influence investment directly under the internal funds theory will be ineffective. For example, a reduction in the corporate tax rate will have little or no effect on investment because, under the accelerator theory, investment depends on output, not the availability of internal funds.

On the other hand, increases in government purchases or reductions in personal income tax rates will be successful in stimulating investment through their impact on aggregate demand, hence, output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Before turning to the neoclassical theory, we should note in fairness to the proponents of the internal funds theory that they recognize the importance of the relationship between investment and output, especially in the long run. At the same time, they maintain that internal funds are an important determinant of investment, particularly during recessions.

Theory of Investment # 3.The Neoclassical Theory of Investment:

The theoretical basis for the neoclassical theory of investment is the neoclassical theory of the optimal accumulation of capital. Since the theory is both long and highly mathematical, we shall not attempt to outline it. Instead, we shall briefly examine its principal results and policy implications.

According to the neoclassical theory, the desired capital stock is determined by output and the price of capital services relative to the price of output. The price of capital services depends, in turn, on the price of capital goods, the interest rate, and the tax treatment of business income. As a consequence, changes in output or the price of capital services relative to the price of output alter the desired capital stock, hence, investment.

As in the case of the accelerator theory, output is a determinant of the desired capital stock. Thus, increases in government purchases or reductions in personal income tax rates stimulate investment through their impact on aggregate demand, hence, output. As in the case of the internal funds theory, the tax treatment of business income is important.

According to the neoclassical theory, however, business taxation is important because of its effect on the price of capital services, not because of its effect on the availability of internal funds. Even so, policies designed to alter the tax treatment of business income affect the desired capital stock and, therefore, investment.

In contrast to both the accelerator and internal funds theories, the interest rate is a determinant of the desired capital stock. Thus, monetary policy, through its effect on the interest rate, is capable of altering the desired capital stock and investment. This was not the case in regard to the accelerator and internal funds theories.

Concluding Remarks:

The policy implications of the various theories of investment differ. It is important, therefore, to determine which theory best explains investment behaviour. We now turn to the empirical evidence. There is considerable disagreement concerning the validity of the accelerator, internal funds, and neoclassical theories of investment.

Much of the disagreement arises because the various empirical studies have employed different sets of data. Consequently, several economists have tried to test the various theories or models of investment using a common set of data.

At the aggregate level, Peter K. Clark considered various models including an accelerator model, a modified version of the internal funds model, and two versions of the neoclassical model. Based on quarterly data for 1954-73, Clark concluded that the accelerator model provides a better explanation of investment behaviour than the alternative models.

At the industry level, Dale W. Jorgenson, Jerald Hunter, and M. Ishag Nadiri tested four models of investment behavior: an accelerator model, two versions of the internal funds model, and a neoclassical model. Their study covered 15 manufacturing industries and was based on quarterly data for 1949-64. Jorgenson, Hunter, and Nadiri found, like Clark, that the accelerator theory is a better explanation of investment behavior than cither of the two versions of the internal funds models. But unlike Clark, they concluded that the neoclassical model was better than the accelerator model.

At the firm level, Jorgenson and Calvin D. Siebert tested a number of investment models, including an accelerator model, an internal funds model, and two versions of the neoclassical model. The study was based on data for 15 large corporations and covered 1949-63. Jorgenson and Siebert concluded that the neoclassical models provided the best explanation of investment behavior and the internal funds model the worst.

Their conclusions arc consistent with those of Jorgenson, Hunter and Nadiri and with regard to the internal funds theory, with those of Clark. Clark concluded, however, that the accelerator model was better than the neoclassical model.

In short, these studies suggest that the internal funds theory does not perform as well as the accelerator and neoclassical theories at all levels of aggregation. The evidence, however, is conflicting with regard to the relative performance of the accelerator and neoclassical models, with the evidence favoring the accelerator theory at the aggregate level and the neoclassical model at other levels of aggregation.

In an important survey article, Jorgenson has ranked different variables in terms of their importance in determining the desired capital stock. Jorgenson divided the variables into three main categories: capacity utilization, internal finance, and external finance. Capacity utilization variables include output and the relationship of output to capacity. Internal finance variables include the flow of internal funds; external finance variables include the interest rate. Jorgenson found capacity variables to be the most important determinant of the desired capital stock.

He also found external finance variables to be important, although definitely subordinate to capacity utilization variables. Finally, Jorgenson found that internal finance variables play little or no role in determining the desired capital stock. This result is, at first glance, surprising. After all, there is a strong, positive correlation between investment and profits. Firms do invest more when profits are high.

However, there is also a strong, positive correlation between profits and output. When profits are high, firms are normally operating at or close to full capacity, thereby providing an incentive for firms to add to their productive capacity. Indeed, when both output and profits are included as determinants of investment, the profits variable loses all or almost all of its explanatory-power.

Jorgenson’s conclusions in regard to the importance of internal funds are, of course, consistent with the results of the tests of alternative investment models. We conclude, therefore, that the marginal funds model is inadequate as a theory of investment behavior.

Jorgenson’s conclusion in regard to the capacity utilization variables lends some support to the proponents of the accelerator model. But he finds external finance variables to be of importance in determining the desired capital stock, which suggests that the neoclassical model is the appropriate theory of investment behavior, since it includes both output and the price of capital services as determinants of the desired capital stock.