Let us make an in-depth study of Keynes’s Contribution towards Economics:- 1. Introduction to the Keynes’s Contribution 2. The Neo-classical View 3. The Keynesian View 4. The Neo-Classical Defence through the Real Balance Effect.

Introduction to the Keynes’s Contribution:

The publication of the General Theory in 1936 had an enormous impact on both economic theory and policy.

Keynes’s contribution has been very influential in the field of macroeconomic policy-making.

The Keynesian demand-management policies were very successfully adopted in the 1950s and the 1960s in western economies in combating unemployment. It is only in the 1970s that the Keynesian policies were questioned and modified.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Neo-classical economists like Marshall, Pigou and Robertson have questioned Keynes’s contribution to economic theory at the time of publication of the General Theory itself. Discussion on basic issues like the under-employment equilibrium had continued for over 25 years.

Basically, the debate has been centred on the question of whether or not a competitive market economy with flexible wages and prices would automatically tend towards a full employment equilibrium position. The neo-classical economists argued that it would do so and, therefore, that all Keynes had done in effect was to add a single assumption to the neo-classical system: the assumption that wages and prices were inflexible downwards because of the existence of trade unions and other restrictive practices (which, of course, was well-known anyway).

Keynesians, on the other hand, attempted to show that a competitive economy, even with completely flexible wages and prices, would not be likely to achieve full employment automatically. Consider how this debate progressed.

The Neo-classical View:

The neo-classical view was that a perfectly competitive economy would always tend towards its full employment equilibrium position. This is illustrated in the three- graph diagram in Fig. 14.13. The upper graph shows the economy’s initial general equilibrium position in the real and monetary’ sectors.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The lower left-hand graph is the short-run aggregate production function and the lower right-hand graph illustrates the economy’s labour market. Notice that for convenience the real wage is measured along the horizontal axis and the quantity of labour is measured along the vertical axis. As drawn, equilibrium in the real and monetary sectors exists at an output level of OY1 which is produced using a quantity of labour OL1. Unfortunately, this is not the full employment quantity of labour: there is an excess supply of labour (or unemployment) equal to BC.

According to the neo-classical economists, this unemployment cannot persist. Assuming that wages and prices are flexible upwards and downwards, the excess supply of labour will cause money wages to fall. As the real wage falls, employment and output rise, but this spoils the equilibrium in the real and monetary sectors of the economy.

In fact, there will be an excess supply of goods and services on the market which will exert downward pressure on prices. The result, then, is a general deflation of both wages and prices which leaves real wages unchanged but which causes the real money supply to increase, so shifting the LM curve to the right to LM’. This deflation, according to the neo-classical economists, will continue until the new equilibrium in the real and monetary sectors is just consistent with equilibrium in the labour market-that is, at point A in Fig. 14.13. Only when this point is reached will the unemployment in the economy have been eradicated.

The Keynesian View:

Keynesians were sceptical of the above mechanism, even assuming flexible wages and prices. In particular, they pointed to two barriers which might exist to prevent the full employment equilibrium from being reached: lack of investment and the liquidity trap.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The possible lack of investment is illustrated in Fig. 14.14 where the IS curve is very steep and cuts the horizontal axis at a point below the full employment level of income Y1. Recall that the IS curve will be steep when investment is very interest- inelastic. In this case, as shown in the diagram, it is impossible for a full employment equilibrium to be reached by means of a shifting LM curve alone.

Recall that it exists where the interest rate is so low that the demand for money becomes perfectly interest-elastic. When the demand for money is perfectly interest-elastic, the LM curve is horizontal, as illustrated in Fig. 14.15.

In this ease, the equilibrium level of income is unaffected by the increase in the real value of the money supply. The LM curve shifts to the right, as shown, but the intersection of the horizontal part of the LM curve with the IS curve is unchanged. What is happening here is simply that the additional real money supply is being held in speculative or ‘idle’ balances.

The Neo-Classical Defence through the Real Balance Effect:

The neo-classical economists, largely through the work of Pigou, produced a counter-argument to the above Keynesian cases in the shape of the real balance effect. According to this, with a constant nominal money supply, a general deflation of wages and prices will tend to increase the real value of people’s holdings of money above their desired levels.

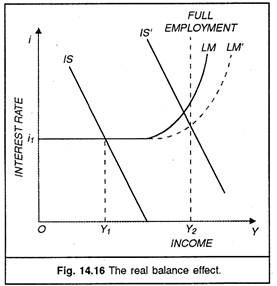

Consequently, people will reduce their savings and increase their consumption in an attempt to reduce their ‘real balances’. In the above cases, where full employment is not reached, as wages and prices fall and the LM curve shifts to the right, the IS curve will also shift to the right as consumption increases. With both curves now shifting to the right, the equilibrium levels of income and employment must increase (even in the liquidity trap and with interest-inelastic investment) and there is now nothing to stop full employment from being reached. This is illustrated in Fig. 14.16.

Theoretically, then, the neo-classical economists appear to have the stronger case. Only when it came to policy-making did the Keynesians have the upper hand, given the recognised inflexibility of wages and prices downwards.