Keynes Underemployment Equilibrium!

If we are to mention the greatest contribution which Keynes made to economic analysis, it is this demonstration that equilibrium of the free enterprise, capitalist economy is not only possible at less than full employment but is also the common situation.

In the classical model such under-employment equilibrium was inconceivable. Less than full employment meant disequilibrium.

When belief in the classical scheme of ideas was so firmly rooted to talk of equilibrium before full employment was simply a daring act. But Keynes’ ideas could carry conviction with a large number of fellow economists because he gave systematic account of how Underemployment Equilibrium could occur.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Having studied Keynes’ system and the classical system we are now in a much better position to understand the logic and the relations behind Keynes’ argument against the classical contentions. Let us outline the classical argument against underemployment equilibrium first.

The Classical ‘Double Defence’ against Underemployment Equilibrium:

Classicals gave two solid reasons for the non-existence of under employment equilibrium. The first reason was related to the flexibility of the rate of interest. Rate of interest occupies a very important place in the classical system. It is treated as the equilibrating mechanism between saving and investment because it brings equality between the two.

In case saving tends to be excessive as compared to the demand for it, the rate of interest brings into operation the forces which reduce saving rendering its supply equal to demand, as the higher rate of saving will bring down the rate of interest thereby affecting the propensity to save and encouraging investment making them equal to each other. The second element correcting disequilibrium in the economy is the wage rate.

It operates in the labour market. Whenever involuntary unemployment occurs in the labour market wages fall under the pressure of competition thereby reducing costs and prices. This increases the aggregate demand in the economy to lift off the market the addition to supply of output made by the additional employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, the classical reasoning was simple. Flexibility of wages and the rate of interest lead to price flexibility which ensures equilibrium of the economy only at full employment. The existence of unemployment and saving-investment inequality in this position was regarded a disequilibrium position in the economy.

Keynes’s Argument for Underemployment Equilibrium:

According to Keynes, income and not the rate of interest is the equilibrating mechanism between saving and investment as presumed by the classical economists. Keynes argued that savings are not very sensitive to the rate of interest they rather depend upon the level of income. Keynes believed that very few people saved to earn a higher rate of interest.

According to him, lower rates of interest alone did not encourage investment as they depended upon the marginal efficiency of capital and other factors. Thus, Keynes condemned the undue importance given to the rate of interest by classicals in bringing about equality between saving and investment at full employment.

We have already seen that according to classicals rate of interest brings automatic adjustment between saving and investment at full employment level. This is because they believed that savings depend upon the rate of interest and rise and fall with a rise and fall in the rate of interest (in other words, to them savings are highly interest- elastic and flow automatically to equal investment at full employment level).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynes, however, challenged the assumptions of the classicals and pointed out that the functional equality between saving and investment is brought about by changes in income (rather than by the rate of interest). He, therefore, concluded that the equilibrium between Sand I is reached considerably below the full employment level.

called the underemployment equilibrium, According to Keynes, as long as the shapes of investment schedule, saving schedule and liquidity (demand for money) schedule are as shown further, investment will not automatically flow to equal saving at full employment level howsoever flexible wages, prices and costs may be. Therefore, what we generally have in the economy is the underemployment equilibrium and not full employment equilibrium.

Keynes explains the existence of underemployment equilibrium with the help of the following assumptions:

1. The investment-demand schedule during a depression is insensitive (inelastic) to the changes in the rate of interest, i.e., even though there is a considerable change in the rate of interest, it has little or no effect on investment.

2. Similarly, savings are also insensitive (inelastic) to small changes in the rate of interest, i.e., even if there is a considerable rise or fall in the rate of interest, it will not lead to any significant rise or fall in the amount of saving if income does not change.

3. Another presumption relates to people’s desire to hold cash (popularly called liquidity function). The liquidity function, according to Keynes, is highly sensitive (elastic) to the changes in the rate of interest. In a depression, the rate of interest falls to an institutional minimum.

People do not expect the rate of interest to fall any more. Let the monetary authority throw any amount of money in the economy, people have an insatiable desire to hold cash.

Additions to the supply of money do not reduce the rate of interest. This is popularly known as the Keynesian liquidity Trap. It tells us that at a particular low interest rate, the liquidity function is perfectly interest- elastic. This is due to the illusion of the people about the inevitability of expected rise of interest rate causing the excessive speculative demand for money.

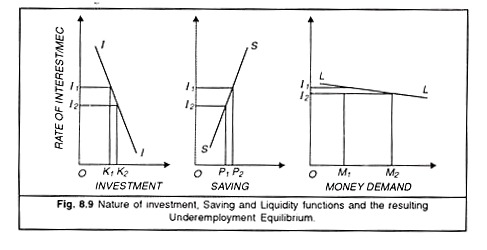

As against the interest- inelasticity of the investment-demand function and the equal insensitivity of the saving function, the liquidity function is highly interest-elastic. The shapes of investment and liquidity (desire to hold money) functions as described above are shown in figure 8.9.

In figure 8.9 (a), a fall in the rate of interest from r1 to r2 does not lead to any significant rise in investment. Similarly, in figure (b) a fall in the rate of interest from r1 to r2 leads to insignificant fall in savings. Both of these functions are interest inelastic. In figure (c) a fall in the rate of interest from r1 to r2 leads to a considerable increase in people’s desire to hold money (liquidity).

The liquidity function is highly interest-elastic. Add to this the worker’s-money illusion in not accepting a lower money wage in the face of unemployment and it becomes fairly clear how the classical interest-wage-price flexibility fails to generate full employment.

In depression the MEC is extremely low, Even when saving is excessive, the rate of interest does not fall- because of the liquidity trap- to adjust itself to the low MEC. Even if the interest rate falls, investment does not get encouraged because of interest inelasticity and savings are not discouraged or consumption encouraged because of interest in elasticities of the saving function.

Thus, with these more realistic assumptions about the shapes of the basic functions of saving, investment and the excessive desire for liquidity of the Keynesian system, it is easy to see that underemployment equilibrium may be the rule in the free-enterprise economy rather than the exception. If the behaviour of the three functions is as described above, underemployment equilibrium would prevail as investments do not tend to flow automatically to equalize the saving flowing at full employment level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The three Keynesian specifies to prove the general prevalence of underemployment equilibrium were:

1. Rigidity of wages in the downward direction because of the money illusion from which workers arid their unions suffer

2. The ‘liquidity trap’ which does not allow the market rate of interest to fall below an institutionally-set minimum; and

3. The interest-inelasticity of the investment-demand function. Now suppose the economy is having some unemployment: even if the unemployed workers are prepared to accept a lower wage than the market rate, employment is not likely to be increased because of the failure of the real wage rate to fall sufficiently to let all the unemployed be absorbed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Even if wages were reduced and hence prices, the rate of interest would not possibly go down much because the cash balances saved from the lower prices will be absorbed by the highly elastic liquidity function without much effect on the rate interest. Even if the rate of interest is reduced, the investment demand is so interest-inelastic that it is unlikely to have any appreciable effect on investment. Thus the depressed economy is very likely to continue in the underemployment equilibrium.

Importance of the Concept:

The theoretical and practical importance of the concept of underemployment equilibrium is clear from the following observations:

1. It must be remembered that underemployment equilibrium is the result of the private underinvestment. It is a characteristic feature of instability of business expectations and private underinvestment. It is a characteristic feature of private enterprise economy in which the investments of private entrepreneurs are guided by profit motive only. In planned and socialist economies where investments were mostly controlled or autonomous (i.e., independent of profit-motives), the problem of underemployment equilibrium did not exist.

2. In a free-enterprise economy investments are not sufficiently induced automatically to offset all the saving done out of full employment income. It is, therefore, clear that if underemployment equilibrium is to be avoided, there must be social control of private investment in such economies. In other words, conditions must be created for increased autonomous investments to flow so as to offset the entire saving by investment at full employment.

3. Keynes’s demonstration that the economic system can be in equilibrium at less than full employment is, no doubt, his major theoretical contribution. It would not be a wrong statement if we say that underemployment equilibrium was the central theme of the General Theory. It served to concentrate attention on underemployment of developed economies.

Economists are no longer satisfied with discussion of the relevant economic problems on the assumption of full employment. “The present interest in full employment economics, in non-wastage of resources, and in short-run economics, owes much to Keynes; probably more to him than to anyone else.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For his General Theory, Keynes built new tools and refined old ones. “Say’s Law of markets, marginal propensity to consume, marginal efficiency of capital and the liquidity function (desire to hold money) are the raw materials out of which Keynes processed the final product-underemployment equilibrium.”

Criticism:

Keynes’ underemployment equilibrium, in spite of its being significant gift to economics, has been the target of much criticism. All the underlying concepts and fundamental relationships on which the concept of underemployment equilibrium is based have been severely criticized on various grounds by writers like Haberler, Hicks, Leontief and others.

The main points of criticism are as follows:

1. Instability of Underemployment Equilibrium:

After a thorough examination of the nature of functions on which the General Theory is based, it has been pointed out by critics that the position of underemployment equilibrium may not be one of stable equilibrium.

Here it is only necessary to point out that underemployment equilibrium in spite of the numerous criticisms continues to be a major contribution of Keynes in the field of macroeconomic theory of the short period. Economists will no longer assume full employment or automatic adjustment in the discussion of unemployment in the treaties on the Trade Cycle.

2. Contradictory Concept:

Prof. Hazlitt has criticized the concept as ‘pure nonsense’. He felt it absurd to talk of equilibrium with less than full employment as it amounts to simply, what may be called a ‘contradiction in terms’. According to him, there cannot be equilibrium with underemployment, and if there is unemployment there must be disequilibrium elsewhere.

3. Oversimplified Assumptions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Smithies and Tobin think that Keynes built his theory of underemployment equilibrium on over-simplified assumptions and, therefore, it is necessary to modify some of these assumptions before we are sure of the underemployment equilibrium.

4. Exists Only in Peculiar Conditions:

Prof. Leontief is highly critical of the universality given to underemployment equilibrium by areas. “I have some-times wondered,” he says, “why Keynes attached so much importance to proving that there ma)’ and under his assumptions generally will be less than full employment in perfect equilibrium of perfect competition.”

5. Only a Temporary Phenomenon:

The concept is relevant only to the short period. In any thinking about the long run, underemployment equilibrium is the first causality because the special forms of the underlying functions are not valid in the long run.

It is based on the assumptions of ‘illusions’ and ‘in-elasticities’ in different markets in the economy which arc irrelevant to long-run (growth) theory. Prof. Wright feels that the concept of underemployment equilibrium, in particular, must be given up.

Keynes assumed the rigidity of money wages and interest in the downward direction. If these assumptions, which are certainly not unrealistic, are followed, most of his conclusions would follow too. Underemployment equilibrium is then possible. “All will not agree” Feels Prof. Harris, “That the underemployment equilibrium is stable. But all will agree that it will receive more attention in economics than before.”

Conclusion:

Using the tools of Say’s Law, the quantity theory, and the assumptions of flexible prices and wages, the classical economists established the proposition that a position of full employment would always be reached in a capitalist economy in the long period and that is only when it would be in equilibrium.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The key assumptions in this chain of causation are:

(1) That people would always prefer to invest their idle cash balances at a positive rate of return instead of keeping them the earning a zero rate of return.

(2) And that there were always sufficient investment outlets for all these funds at some positive rate of return.

In the light of these and foregoing observations, we can say that the principal difference between the Keynesian and the classical type of analysis would appear to be procedural rather than substantial. With its set of basic assumptions formulated without reference to the dynamic aspects of the short period unemployment problems, the classical approach suffered from what might be called theoretical farsightedness, the ability to appraise correctly the long run trends coupled with a singular inability to explain or even to describe the short-run changes and fluctuations.

The Keynesian lenses improve somewhat but do not really correct the analytical vision so far as the short-run phenomena are concerned. However, they put entirely out of focus the long-run views of economic growth.