Keynes’s Liquidity – Preference Theory of Interest Rate!

Introduction to Keynes’s Liquidity – Preference Theory of Interest Rate:

In his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, J.M. Keynes propounded his theory of interest called the Liquidity Preference Theory.

Keynes considered rate of interest to be a purely monetary phenomenon determined by the demand for money and supply of money.

He called the demand for money ‘liquidity preference’. He expressed the opinion that every person who has saving has to decide how he is to keep his saving: in the form of ready money which does not bear any interest or lend it to buy interest-bearing claims like bonds and securities?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If he keeps his saving in the form of cash or ready money, he has the advantage of complete negotiability of his saving, of putting it to use any way, anywhere at any time. In other words, if he keeps his saving in the form of cash he enjoys the advantage of liquidity of his saving.

On the other hand, if he purchases interest-bearing securities, he gets some income in the form of interest but these claims are not liquid like money. Due to certain reasons to be explained shortly, every person likes to hold cash or wants to be liquid.

One thus has liquidity preference. It is this liquidity preference which makes people demand money to hold, or to have an equal amount of cash rather than claims against others.

Keynes was of the opinion that factors like abstinence and time preference have nothing to do with the payment of rate of interest. Interest is not compensation to the saver for the abstinence he has undergone or time preference he has. It is “the reward for parting with liquidity for a specific period.” In other words, rate of interest was to Keynes the reward for accepting a claim like bond and security in lieu of money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Everybody has an innate desire to hold his saving in the form of cash rather than in the form of interest or other income-bearing assets. The keenness of the desire to hold money measures the extent of our anxiety about uncertainties of the future.

Lord Keynes wrote:

“The possession of actual money lulls our disquietude; and the premium which we require to make us part with money is the measure of the degree of our disquietude.” Thus, according to Keynes, interest is the reward necessary to induce a person to part with his liquidity—the reward to make him part with his cash and accept interest-bearing, non-liquid claims in its place.

In Keynes’s liquidity-preference theory, the demand for money by the people (their liquidity preference level) and the supply of money together determine the rate of interest. Given the supply of money at a particular time, it is the liquidity preference of the people which determines rate of interest. This is the essence of Keynes’s theory. The level of liquidity preference, Keynes wrote, depends upon a number of considerations which can be classified into three broad motives for liquidity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These are the transactions, precautionary and speculative motives. These three motives constitute the components of the demand for money. It is on these motives that the level of demand for money or liquidity preference depends. We turn to the analysis of these three motives first and then with some remarks about the supply of money study the determination of the rate of interest as Keynes taught us.

The Demand for Money or Liquidity Preference:

The three motives for keeping liquid are the transaction motives, the precautionary motive and the speculative motive. There are three reasons for which money is demanded.

We study them in detail:

1. Transaction Motive:

Transaction motive refers to the demand for money for current transactions by households and firms. Households need cash so as “to bridge the interval between the receipt of income and its expenditure.” Between the periods of receiving pay packets, house-holders have to enter into transactions for meeting their daily needs.

People are paid weekly or monthly while they spend day after day. A particular amount of cash, therefore, has to be kept for making purchases. The amount of cash needed for current transactions by a particular household depends upon its size of income, the interval of time after which income is received and the mode of payment.

Likewise firms also need cash to meet their current needs like payment of wages, purchases of raw materials, transport charges etc. The demand for money for transactions by firms also depends upon the income, the general level of business activity and the manner of the receipt of income.

The greater is the turnover of business and income from it, the greater is the amount of cash needed to meet it. Obviously the transaction demand for money depends upon income. In symbols we can write, M1 = f (Y), where M1 is the transaction demand for money and f(Y) shows it to be a function of income.

2. Precautionary Motive:

Households and business concerns need some money for precautionary purposes because they have to take precaution against unforeseen contingencies like sickness, fire, theft and unemployment. The amount of cash needed for taking this precaution will depend upon an individual’s psychology, his views about the future and the extent to which lie wants to ensure protection against such unforeseen events.

Similarly, businessmen also hold cash to safeguard against the uncertainties of their business. Clearly, greater is the turnover of business and the income there from, greater is the amount of cash a business firm will keep to satisfy its precautionary motive. Whether it is an individual or a firm, for both the amount of cash money needed to satisfy their precautionary motive depends upon their income more than anything else. We can write, therefore, that M2 -g(Y), where,M2 is the demand for money due to precautionary motive and g(y) shows it to be a function of income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since both the transactions and the precautionary motives for holding cash depend upon income, Keynes put them together. Both these motives form the first component of the demand for money and both are income-elastic. Thus, M1 +M2 = L1 =f (Y), which means that the demand for money on account of the two motives, called L1, is a function of income

L1=f(Y)

3. Speculative Motive:

The third and most important motive of the demand for money is the speculative motive. Keynes assumed that people hold either cash or bonds as wealth. They shift-from cash to bonds as they expect the rate of interest to change. People keep cash with them to take advantage of the changes in the price of bonds and securities in the capital market. In advanced countries, of which Keynes was writing, people like to hold cash for the purchase of bonds and securities when they think it profitable.

If people expect that the prices of bonds and securities are going to rise, they like to purchase them, for they are attractive, and do not keep cash with them. On the other hand, when they feel that the prices of bonds and securities are going to fall in the near future, they get detracted away from them and demand more cash. This speculative propensity of the people can be satisfied only with cash and it depends upon expected changes in the prices of bonds and securities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A fundamental fact noted in the capital market is that the prices of bonds and securities change inversely with the change in the rate of interest. When the rate of interest rises, the prices of bonds and securities fall and with a fall in the rate of interest, bond and security prices go up. This inverse relationship between the market rate of interest and the price of a bond or security can be accounted for and illustrated like this.

Suppose a person purchases a bond of the face-value of Rs. 1,000/- earning a fixed rate of interest of 4 per cent per annum. This bond is thus an income-yielding asset of 40 rupees per year. This bond is to give an income of 40 rupees per year to its owner, whatever its market value. Now suppose the market rate of interest rises to 5 per cent per annum. At this higher rate of interest, a bond of the face value of Rs. 800/- newly floated by a company will bring 40 rupees per annum while the old bond of the face value of Rs. 1,000/- will also be bringing in 40 rupees.

Therefore, the market value of the old bond will fall to Rs. 800/- giving its owner a capital loss of Rs. 200. This shows that the price of the bond of Rs. 1,000falls to Rs. 800 when the market rate of interest rises from 4 to 5 per cent per annum. Similarly we also find that if the market rates of interest falls from 4 per cent per annum to 2 1/2 per cent per annum, the market price of the bond of a face value of Rs. 1,000/- bearing 40 rupees income per annum will rise to Rs. 1,600. The fact that prices of bonds change inversely with rate of interest is clear.

People keep cash with them to speculate on the prices of bonds and securities which change inversely with the rate of interest. If people expect the rate to rise in future—that is, they expect the prices of bonds and securities to fall—they would be induced now to keep more cash with them. On the other hand, if they expect the rate of interest to fall—that is, the bond and security prices to rise—they would be induced to have more bonds and securities rather than cash.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, the amount of cash which the people wish to hold for speculative motive depends upon the expected change in the rate of interest. The changes in the demand for money for holding it to satisfy the speculative motive are due to the future uncertainty of the rate of interest; change in expectations about its future course causes a change in the speculative demand for money now.

The speculative motive for money thus becomes a link between the present and the future. The speculative motive for liquidity- preference thus introduces a dynamic element in the Keynesian theory. Since the speculative demand for money depends upon the expected future changes in the rate of interest, we can write

L2=g(r)

where L2 is the speculative demand for money and it is a function of the expected changes in the rate of interest.

It should be noted that the liquidity preference due to transactions and precautionary motives is dependent on the level of income while that for speculative motive is a function of the expected changes in the rate of interest. We may write the total liquidity preference like this: L1 (y) + L2 (r). Keynes gave the primary role to the speculative motive for holding money and did not include the first two motives in his theory of the rate of interest.

This is because the liquidity preference on account of transaction motive and precautionary motives is stable and almost interest-inelastic while that for the speculative motive is specially sensitive to changes in the rate of interest. In his theory of the rate of interest, Keynes considered the demand for money- liquidity preference—to be composed of the speculative demand for it only because the demand for cash balances arising out of the other two motives is comparatively insignificant in the determination of the rate of interest in the short run.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

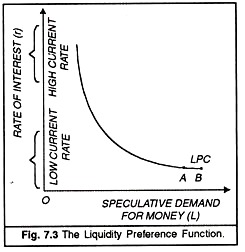

The Keynesian liquidity preference schedule relates the various rates of interest to the levels of demand of money. It is a demand curve for money and slopes from left down to the right as shown in Fig. 7.3. In this figure, rate of interest is shown on the ordinate axis and the demand for money on the co-ordinate axis.

The shape of liquidity preference curve is accounted for in Keynes’s analysis like this: When the market rate of interest is high, people expect it to fall in future and the prices of bonds and securities to go up. For them, therefore, bonds and securities are attractive since they expect capital gains from them and cash is less attractive: the demand for cash is, therefore, low.

If the current rate is low, people expect it to rise in the future or expect the prices of securities to fall. Since bonds and security-holders are expected to suffer a capital loss, people are more attracted to cash; therefore, they demand a larger amount of cash. Thus, at high current rates of interest, liquidity preference is low. In other words, the demand for money is inversely related to the expected changes in the rate of interest.

Discussing the shape of the liquidity preference curve, Keynes went a step farther to highlight a peculiar feature of it. He gave the hypothesis that at extremely low rates of interest, the liquidity function (curve) becomes perfectly elastic, that is, parallel to the co-ordinate (X) axis, as is shown in the portion AB of the liquidity preference curve in Fig. 7.3. This feature of the liquidity function is called the ‘liquidity trap’ since it shows that at a particular low rate of interest, people possess an insatiable demand for money. This feature has important implications for public policy which we need not discuss here.

Supply of Money:

Supply of money, at a particular time, is given to the economy by the government and the credit-creating power of the banks. Money supply depends upon the currency issued by the government and the policy followed by the Central Bank of the country.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

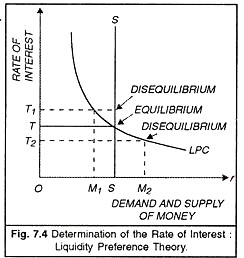

Supply of money cannot be privately increased like that of commodities. Money is a given stock at a moment of time. Therefore, the supply function of money is a straight line parallel to the ordinate (Y) axis, as is shown in Fig. 7.4 by the straight line SS.

Determination of the Rate of Interest:

According to Keynes, the equilibrium rate of interest is determined at the point where the given supply of money is equated to the level of liquidity preference. In figure 7 .4 money supply is given as OS and the level of liquidity preference by the curve LPC. ‘Or’ is the equilibrium rate of interest, for at this rate the amount of money demanded is equal to its supply. At any other rate money demand would be either more or less than money supply. Take, for example, the rate of interest Or1. At this rate of interest the demand for money is OM1 while the money supply is OS.

There is an excess supply of cash of the amount of M1S which people do not want to hold or which they like to invest in bonds and securities. There is disequilibrium in the money market. Bonds’ and securities’ prices will go up and the rate of interest will go down till people want to hold the amount or cash, bonds and securities equal to their supply. Likewise, if the money supply is less than the demand for it, the rate of interest will rise. Suppose the rate of interest is Or2 at which money demand is OM2 while the supply is OS.

There is an excess demand for money (cash) to the tune of SM2 which the people would try to satisfy from the sale of bonds and securities whose prices would consequently fall. Rate of interest would rise till it is at the level Or. There would be equilibrium in the bonds and securities market at this rate where the demand for and supply of cash would also be equal. Change in the rate of interest thus takes place whenever there is disequilibrium between people’s demand for and supply of either cash or bonds or securities.

It should be noted that the money supply and the level of liquidity preference are entirely independent and the two arc brought together only by changes in the rate of interest. Any one of these two may change to bring about a change in the rate of interest. The Central Bank of the country may increase money supply to lower the rate of interest. But this will take place only if the level of liquidity preference remains where it is.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If the expectations of the public change and cause an upward shift of the liquidity schedule or curve, the rate of interest may remain where it is. Or if the rate of interest is already very low and the liquidity preference curve is infinitely interest- elastic (liquidity trap situation), the Central Bank’s increased money supply may entirely go to meet the demand for idle balances which in this situation is insatiable. The central Bank’s action may not lower the rate of interest at all. This was the position during depression.

Thus we see that the Keynesian explanation of the determination of the rate of interest was all in terms of monetary factors. He concentrated his attention on the rate of interest as a monetary phenomenon and thereby gave us valuable insights into the process of adjustment in the money and capital markets for bringing about changes in the interest rate.

Conclusion:

We thus reach the conclusion that Keynes’s theory has also got its shortcomings. Keynes was no doubt correct in giving importance to money in his theory but then he completely disregarded all other factors. The exponents of the loanable funds theory duly incorporated the liquidity preference idea into their theory through their analysis of hoarding and dishoarding. D. Hamberg remarks justifiably: “Keynes did not forge nearly as new a theory as he and others at first thought.

Rather his great emphasis on the influence of hoarding on the rate of interest constituted an invaluable addition to the theory of interest as it had been developed by the loanable fund theorists who incorporated much of Keynes’s ideas into their own theory to make it more complete.” Nevertheless, Keynes’s theory remains a distinct theory on its own in so far as it is entirely monetary.

It does not give any place to such real factors as productivity and thrift. He did not agree with the neoclassical view that the rate of interest is determined in part by the marginal revenue productivity of capital due to its influence on the demand for investment. This is because Keynes held that rate of interest does not bring about equality of saving and investment; in his view it is income that does so.

It is here that the Keynesian liquidity preference theory assumes an altogether different role in the determination of income, output and employment from that given to the loanable funds theory by the neoclassical. Keynes’s theory, to spite of its deficiencies, did serve to analyse some fundamental features of the money and capital markets which the loanable funds theorists had failed to do.

Conclusion on Keynes versus Neo-classicals:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Liquidity preference is actually a choice between many types of assets. It is obvious “that the demand and supply of ever)’ type of asset has just as much right to be considered as the demand and supply of money. Unless we consider as equally important the different types of financial investments including money, we have no way of explaining the co-existence of different rates of interest. The perfect interchangeability of all units of money makes it impossible for the liquidity- preference theory to account for the phenomenon of diverse rates on the various parts of the credit market.”

Keynes’s Liquidity-Preference Theory is not necessarily at conflict with the classical or neoclassical theory. As D.H. Robertson has pointed out, “the fact that the rate of interest measures the marginal convenience of holding idle balance need not prevent it from measuring also the marginal inconvenience of abstaining from consumption.” With these brief remarks we now return to the study of the main merits of Keynes’s theory.

Merits of Keynes’s Liquidity-Preference Theory:

Keynes’s liquidity-preference theory has some distinct merits over the classical theory.

These merits are as follows:

Firstly, Keynes’s theory is a monetary rather than a real theory. It ought into spotlight the role of money in the determination of the rate of interest.

Secondly, Keynes’s theory of the interest rate is more general than the classical theory in that it is applicable not only to full-employment economy but also to the state of less than full employment.

Thirdly, Keynes’s theory helped integrate the theory of money to the general theory of output and employment. The classical theory was devoid of any monetary influence because classicals would consider money only as a veil or a medium of exchange: the store of value function was entirely ignored. The classical theory being static in nature did not consider the uncertainty about the rate of interest and its influence on the present. Keynes’s theory is to this extent much more dynamic and as such more realistic.

Fourthly, the liquidity-preference theory, through its ‘liquidity trap hypothesis’ stresses the limitation of monetary and banking policy and its ineffectiveness during the period of depression.

Fifthly, Keynes amply made it clear that interest is not and income is the equilibrating mechanism between saving and investment. This made it possible to build up a theory of income. Further, by including marginal efficiency of capital as the major determinant of investment, Keynes freed the rate of interest from the onerous tasks given to it in the classical theory,

Keynes, thus, presented a comprehensive analysis of the monetary sector. He also provided a link between the monetary and the real factors and thus paved the way for an integrated, determinate theory of the rate of interest which J.R. Hicks could ultimately formulate. Despite some flaws in Keynes’s treatment of money and the rate of interest, we cannot minimize the importance of Keynes’s valuable contribution to the apparatus and policy about rate of interest.