The following points highlight the six important exceptions to the law of demand. The exceptions are: 1. Speculative Demand 2. Snob Appeal or Veblen Good 3. Using Price as an Index of Quality 4. Giffen Good 5. Possibility of Future Rise in Prices 6. Highly Essential Good.

Law of Demand: Exception # 1.

Speculative Demand:

In a speculative market (such as the stock market), a rise in the price of a commodity (such as, share) creates an impression among buyers that its price will rise further. So people start buying more of a share when its price rises. This is not truly an exception to the law of demand in the sense that the demand curve here is not upward sloping.

Hence, there is no movement along it from left to right. In fact, in a speculative market, we see a shift of a normal downward sloping demand curve— people buy more at the same price. Some people wrongly refer to this as an exception because they get confused between the two issues—movement along a demand curve and a shift of the demand curve.

Law of Demand: Exception # 2.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Snob Appeal or Veblen Good:

People sometimes buy certain commodities like diamonds at high prices not due to their intrinsic worth but for a different reason. The basic object is to display their riches to the other members of the community to which they themselves belong.

This is known as ‘snob appeal’, which induces people to purchase items of conspicuous consumption. Such a commodity is also known as Veblen good (named after the economist Thorstein Veblen) whose demand rises (fails) when its price rises (falls).

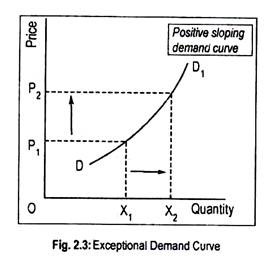

This is a genuine exception to the law of demand. The demand curve for such an item will be upward sloping (Fig. 2.3). Thus if, the price of diamond falls, people will buy less of it. In a word, purchasers value diamonds and other costly items because of their prices and because of the psychic satisfaction that they derive from it.

Law of Demand: Exception # 3.

Using Price as an Index of Quality:

Most consumers do not have the capacity or technical knowledge to examine the physical properties of a product (such as, reliability, durability, economy, etc.,) as in the case of an item such as a motor car or a VCR. So, in the absence of other information, price is taken as an index of quality. Thus, a high-priced car is more valued than a low-priced one.

A costly book is often considered to be more useful by a student than a cheaper title. In such cases, the demand curve may be upward sloping. This argument is not a new one. This applies to our previous case where we referred to commodities having snob appeal. So this point really reinforces the previous one.

Law of Demand: Exception # 4.

Giffen Good:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A ‘Giffen good’ is a special variety of inferior good. Sir Robert Giffen of Scotland observed in the 19th century (1840s) that poor people spent the major portion of their income on a staple item, viz., potato. If the price of this good rises they will become so poor that they will be found to spend less on other items and buy more potatoes in order to get a minimum diet and keep themselves alive.

For such goods, the demand curve will be upward sloping. It will look like the supply curve of a commodity of Fig. 2.3. Note that this is a very exceptional case and potatoes that we consume today should be considered as ‘normal good’ rather than Giffen good.

Law of Demand: Exception # 5.

Possibility of Future Rise in Prices:

If a consumer anticipates that the price of a commodity will rise in future he will purchase more of that commodity now. The consumer will purchase more even if current price is high.

In all the cases mentioned above, the demand curve DD1 exhibits positive slope as shown in Fig. 2.3. At a price OP1, a consumer demands OX1 of a commodity. As its price rises to OP2, demand also rises to OX2. Thus, the law of demand breaks down.

Law of Demand: Exception # 6.

Highly Essential Good:

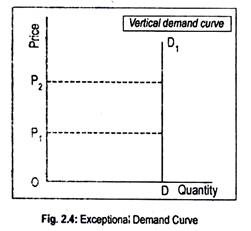

Finally, in case of certain highly essential items such as life- saving drugs, people buy a fixed quantity at all possible price. Heart patients will buy the same quantity of ‘Sorbitrate’ whether price is high or low. Their response to price change is almost nil.

In cases of such commodities, the demand curve is likely to be a vertical straight line (Fig. 2.4). At a price OP1, the heart patient consumer demands OD amount of ‘Sorbitrate’. In spite of its price rise to OP2, the consumer buys the same quantity of it.