We know that demand varies with price. So we can formulate the Law of Demand.

This law says that demand varies inversely (in the opposite direction) with price, i.e., if the price rises, demand contracts, and if the price falls, demand extends.

In other words, demand increases with a falling price and decreases with a rising price.

“At any given time, the demand for a commodity or service at the prevailing price is greater than it would be at a higher price and less than it would be at a lower price.” The qualifying phrase ‘at any given time’ is very important, for demand is different at different times and under different conditions, even if the price does not alter.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Exceptions to the Law of Demand:

The law of demand seems to be applicable to all situations concerning a consumer’s demand.

But there are certain exceptions:

(i) Conspicuous Consumption:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Where a consumer regards the consumption of a commodity as a mark of distinction, he will go in for a high-price commodity, e.g. diamonds. Such consumers measure the utility of a commodity entirely by its price. Hence more will be purchased when its price goes up, whereas according to the Law of Demand, less is purchased at a higher price than at a lower price.

(ii) Giffen Paradox:

Sir Robert Giffen observed in the mid – 19th century that when the price of bread increased, the low-paid workers in Britain spent more on it (Since it was their staple food) and they cut on meat. That is, they substituted bread for meat. This means that the demand for bread increased when its price went up, which is obviously an exception to the law of demand.

(iii) Changes in Expectations:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When prices are expected to continue rising, people, in order to avoid paying more in future, buy more even though the price has risen.

(iv) Trade Cycles:

In times of general economic prosperity, people buy more even when the price goes up, since people’s incomes have gone up. Opposite is the case when there is a general depression in the economy.

(v) Different Brands:

It often happens that different brands of commodities arc priced differently. Some persons conscious of their higher status buy more of the higher-priced brand than the lower-priced brand, because the former are regarded as status symbols.

(vi) Other Miscellaneous Situations:

If a commodity goes out of fashion, its demand may fall despite its falling prices. When a shortage of a commodity is feared, more of it may be purchased even if its price in the market is raising, since producers, traders and consumers all develop a hoarding psychology. Or people may not buy more of a commodity, notwithstanding a fall in its price, simply because they may not be aware of such a fall.

It will, however, be seen that the cases mentioned above arise under special circumstances, while basically the Law of Demand must operate in normal circumstances. All the above types of exceptional demands are represented by exceptional demand curves, i.e., curves rising upwards instead of sloping downwards.

Increase and Decrease and Extension and Contraction of Demand:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The law of demand discussed above relates merely to the extension and contraction of demand. When the demand changes merely because the price has changed, it is a case of extension, or contraction. Increase and decrease are different. Let us understand the difference.

Increase and Extension:

If a man buys more milk because its price has fallen, it is an extension of demand. But if the demand changes independently of the prices, that is, a man buys more not because the price has fallen but for some other reason, e.g., due to a rise in his income, it will be called an increase of demand.

In sum, Extension of demand means more demand at less price.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Increase in demand means greater demand at the same price or the same quantity demanded at a higher price. An increase in a consumer’s demand signifies that he is prepared to spend a larger amount of money on a commodity than before on account of some changes in his circumstances, e.g.. Increase in his income or increase in the size of his family.

Decrease and Contraction:

If a man buys less when the price rises, it is simply a case of contraction of demand. But if he buys less irrespective of the price, it means a decrease in demand. In the case of a decrease in demand, a consumer may, owing to change in fashion or other circumstances, buy less of a good even when the price remains the same or may continue buying the same quantity as before in spite of a fall in price.

In sum, Contraction of demand means less demand at a high price.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Decrease in demand means less demand at the same price or the same quantity demanded at a lower price.

Diagrammatic Representation:

Shift of and Movement along the Demand Curve:

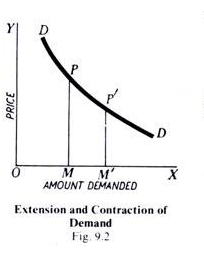

Fig. 9.2 illustrates extension and contraction of demand. When the price falls from PM to P’M’, demand extends from OM to OM’. On the other hand, if the price rises from P’M’, to PM, the demand contracts from- OM’ to OM. Here we travel up and down on the same curve signifying that the demand changes only due to a change in price. This is a movement along a given demand curve.

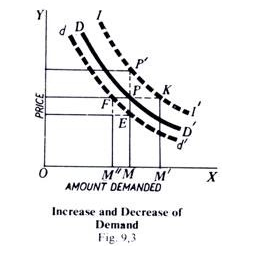

Fig. 9.3 illustrates an increase and decrease in demand. Hence we get entirely new curves (the dotted ones) above or below the old curve. The demand curve has shifted or there is a shift in the demand curve. It shows that the conditions of demand have changed altogether. Take the curve II’.

This illustrates an increase or a rise in demand. Formerly, we purchased OM at the price PM. But now we buy OM at P’M price, which is higher; we buy the same quantity but at a higher price. Or we buy more than before (OM’) at the same price (KM’=PM). In the same way, the lower dotted curve dd’ illustrates a decrease in demand.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Determinants of Demand:

A change in demand means an increase or decrease in demand, and not merely extension or contraction of demand. Therefore, when we want to know why demand changes, we have to mention such factors as create new conditions of demand so that the demand curve either shifts upwards (as II in Fig 9. 3 above) or it shifts downwards (as dd’). Obviously these factors are other than price.

The following are the factors (other than a change in price) which bring about changes in demand:

Change in Fashion:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When some goods go out of fashion, they will be less in demand, even though they may become cheap.

Change in Weather:

It has the same effect as a change in fashion. Demand changes when the weather changes. A fall in the price of woolen clothes does not increase their demand in summer.

Change in the Quantity of Money in Circulation:

If the quantity of money in circulation increases, the people will have more purchasing power. Demand will consequently increase. This is the position in which we find ourselves at present. There has been inflation, demand has increased and prices have risen. A decrease in the quantity of money similarly works in the opposite direction.

Change in Population:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A change in the size or the composition of population will bring about a change in demand. If the birthrate increases in a country, more toys and perambulators will be .demanded; while another country with more old men will demand more walking sticks, false teeth and medicines.

Change in Wealth Distribution:

Suppose wealth comes to be more evenly distributed. The demand for necessaries, and comforts commonly used by the poor people will increase, while the demand for luxuries, on the other hand, will fall off.

Change in Real Income:

Increase in real income means that things are cheap so that with the same money income people are able to buy more goods. It is not necessary that they should buy more of necessaries. The whole scheme of expenditure will be recast and the demand for commodities will, therefore, change. Some comforts might be added and even luxuries.

Change in Habits, Tastes and Customs:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Demand also depends on the tastes, habits and customs of a community. A change in any of these must bring about a change in demand. For example, if people develop a taste for tea in place of lassi, the demand curve for tea will shift upwards towards the right. That is, the demand for tea will increase.

Technical Progress:

Inventions and discoveries bring new things in the market with the result that old things are no longer wanted. For example, radio sets have now replaced gramophones, and TV sets are replacing the radio sets.

Discovery of Cheap Substitutes:

Manufacture of vegetable ghee has made available a cheap substitute for ghee. The demand for pure ghee has consequently decreased.

Advertisement:

A clever and persistent campaign of advertisement may create a new type of demand. This is the case with the demand for patent medicines and toilet accessories.

These are some of the factors that bring about a change in demand irrespective of a change in price.

Inter-Related Demands:

We have been discussing demand as if the demand for a commodity stands by itself. Actually this may not be the case. Demand for one commodity may be connected with that for another, and often it is.

Joint Demand:

When several things are demanded for a joint purpose, it is a case of a joint demand. Milk, sugar and tea leaves are wanted for making tea. Bricks, mortar, wood, and the services of carpenter’s arid masons are all needed for building a house. These are cases of joint demand.

A commodity may be demanded jointly with others in many groups. Milk, for instance, is wanted not merely for making tea, coffee, and oval-tine, but it is also wanted for preparing ‘rasgullas’ and ‘barfi. When commodities are jointly demanded, their prices are influenced by the demand for the ultimate object. For example, the price of bricks and the wages of masons are greatly affected by the demand for houses. The price of each constituent will depend on how urgently it is needed.

Direct and Derived Demand:

In the above example, the demand for the ultimate object, e.g., a house, is called Direct Demand, while the demand for the various kinds of labour and materials which go to make the final product is called Derived Demand. Demand for bricks and mortar is derived from the demand for a house. It is really the house that we want; other things are wanted only because we want a house.

Composite Demand:

The demand for a commodity that can be put to several uses is a composite demand. It is composed of the demand for each of the several uses. Coal can-be used for heating, cooking and for running steam engines. Demand for coal is, therefore, composed of its demand for all these uses. It is thus a case of composite demand.

Complementary and Competitive Goods:

Complementary goods are also called Complements and competitive goods are called Substitutes. Complements are required together, e.g., horse and carriage, tea and sugar, pen, ink and paper, bread and butter, and so on. Substitute means either this or that. Examples of substitutes are tea and coffee fountain pen and ball point pen, wheat and rice, dal and vegetables, dalda and pure ghee, and so on.

We find in such cases that the demand for one good is influenced by the price of another good. That is, a change in price of a good may raise/lower the demand for another good. A fall in the price of one good may either raise the demand for another good or lower it. In the case of complements, a fall in the price of one good, say bread will raise the demand for another good i.e. butter. But, in the case of substitutes, a fall in the price (say of tea) will result in the fall in the demand for another, say coffee.