The Model of Franco Modigliani of Limit-Pricing: Assumptions, Preparation and Other Details!

The Assumptions of the Model:

Modigliani relaxed the restrictive assumptions which underlie Sylos’s model, but retained the assumption of scale-barriers and the behavioural pattern of Sylos’s Postulate.

Modigliani’s assumptions may be stated as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

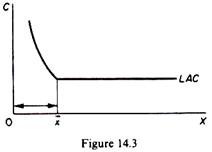

1. The technology is the same for all firms in the industry. There is a minimum optimal plant size (x) at which the economies of scale are fully reaped. Once the minimum optimal scale is reached the LAC becomes a straight line. Under these conditions the LAC is L-shaped (figure 14.3) and is the same for all firms.

2. Entry occurs with the minimum optimal plant size. Entry with suboptimal size is precluded because in the long run it would imply irrational behaviour. There is an implicit assumption regarding entry, namely that entry comes from new firms.

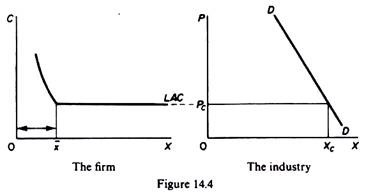

3. The product is homogeneous and the market demand is known. The point of intersection of the given demand curve with a line drawn at the level of the flat section of the LAC determines the competitive output Xc and the competitive price Pc, that is, the price and quantity that would be sold at that price in the long run if the market were purely competitive, given that in the long run equilibrium LAC = Pc (figure 14.4).

4. The price is set by the largest firm in the industry, at such a level as to prevent entry.

5. The firms behave according to the Sylos’s Postulate. That is, the existing firms expect that the entrant cannot enter with a plant smaller than the minimum optimal scale x, and that he will not enter if he believes that the price post-entry will fall below the flat segment of the LAC. The entrant expects that the established firms will keep their output constant at the pre-entry level.

The Model:

Under the above assumptions the equilibrium price PL will be higher than the Pc (= LAC). The established firms will earn abnormal profits due to the scale-barrier which is reflected in the minimum optimal plant size x.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

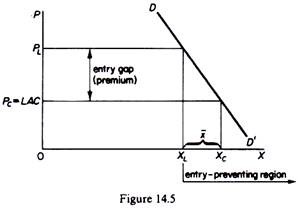

The main preoccupation of the firms is the determination of price at a level which will not attract entry. The limit price PL is determined indirectly by determining the total output which will be sold by all firms in the industry. The established firms decide to sell a quantity XL such that if the entrant comes and offers an additional quantity x (the minimum he can produce optimally), the total output in the market will just exceed the competitive output Xc, and the price would fall just below the Pc = LAC level (figure 14.5). Symbolically this behaviour may be stated as follows the entry-preventing output is XL, such that XL + x > Xc, and the post-entry price falls to P < Pc (where Pc = LAC).

Given XL, the entry-preventing price PL is simultaneously determined from the given industry-demand curve. Entry will be prevented as long as X > XL. If X < XL entry will occur. In figure 14.5 DD’ is the industry-demand curve, x is the minimum optimal level of output, XL = Xc — x is the output which the established firms should produce in order to prevent entry, and PL is the entry-preventing price, defined from the demand curve, given XL. The scale-barriers cause PL to be higher than Pc. The difference PL – Pc is the entry gap or premium and defines the amount by which the price can exceed the LAC without attracting entry.

The determinants of the entry gap and the entry-preventing price are:

(1) The absolute market size Xc

(2) The price elasticity of demand e

(3) The minimum optimal scale x

(4) The prices of factors of production, which together with the technology determine the LAC, and hence the competitive price Pc.

Modigliani reaches the same conclusions as Sylos; namely that there is a determinate equilibrium price PL, which is positively correlated with x and Pc (= LAC), and negatively correlated with the absolute market size Xc and the elasticity of demand e. The limit price will be higher, the larger x, the higher the Pc, the smaller the Xc and the smaller the price elasticity e.

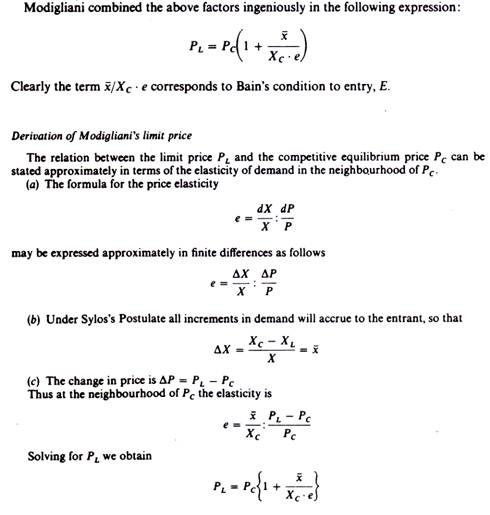

Note that the approximation of the price elasticity with finite changes is not satisfactory for large values of

x/XC = X1 – XC / XC

In particular, if the demand curve has constant elasticity, then for large values of x/Xc the premium (price rise) will be significantly underestimated. (Modigliani, ‘New Developments on the Oligopoly Front’, p. 218.)

The Determinants of the Limit Price:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

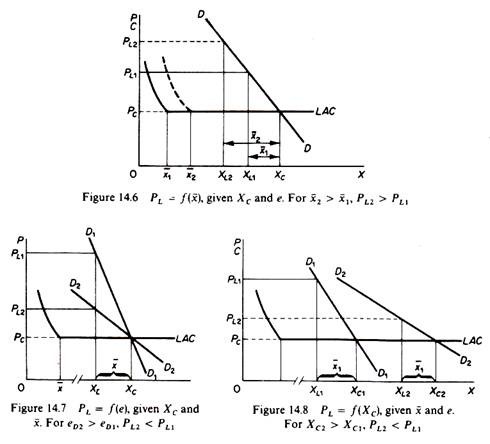

From the above expression it is clear that the limit price PL will be higher the larger the minimum optimal scale of plant x, the less elastic the demand curve and the smaller the absolute size of the market Xc at the competitive price Pc. The relationship between PL and each one of the above determinants is graphically shown in figures 14.6, 14.7, and 14.8.

In figure 14.6 we show the relationship between the limit price PL and the minimum optimal scale of plant x, for given Xc and e. The larger minimum optimal scale x2 allows the established firms to charge a higher limit price PL2 without attracting entry.

In figure 14.7 we show the relationship between the limit price PL and the elasticity of demand e, for given Xc and x. At Pc the demand curve D2 is more elastic than D1. Consequently the price that the established firms will charge is PL2, lower than PL1 which corresponds to the less elastic demand curve D1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally, in figure 14.8 we show the relationship between PL and the competitive equilibrium market size Xc, for given x and e. The larger the Xc, the lower the limit price.

Dynamic Changes in the Market:

Increase in Costs:

If costs change, all firms are affected and hence the long-run cost curve will be raised more or less uniformly. This development will lead to a rise in the limit price. Firms in oligopolistic markets adhere to ‘average-cost’ pricing, because it facilitates the orderly working of the market mechanism.

The full-cost pricing (which consists in applying to the new prime cost the original total percentage mark-up) may well represent a very useful rule of thumb in reacting to cost changes affecting the entire industry. In an oligopolistic situation, with its precarious internal equilibrium, there is much to be gained from simple and widely understood rules of thumb, which minimize the danger of behaviour intended to be peaceful and co-operative being misunderstood as predatory or retaliatory. (Modigliani, ‘New Developments on the Oligopoly Front’.)

Cyclical variations in Demand:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Modigliani agrees with Sylos’s main conclusions concerning the variations in price and the gross profit mark-up over the various phases of the cycle.

(a) In a Recession:

The limit price will show a mild tendency to rise. However, the mark-up may not rise due to the costs of idle capacity, which will push the firms to give secret price concessions in their eagerness to secure a larger share of the smaller demand.

(b) During Recovery:

There will be a tendency for the price to rise, when full capacity is reached. However, large firms may strongly resist this tendency due to fear of potential entry. Instead they will adopt other policies such as allowing a backlog of demand or instituting informal rationing of their deliveries, while at the same time expanding capacity.

The mark-up will tend to retrace the sliding path followed in the contraction, and will stabilize at its normal level, corresponding to the normal ‘price line’ of the large firms. In general the mark-up (on the average) is not likely to change over the cycle appreciably, but one should expect some scatter around this central tendency; prices would tend to show little or no fluctuation over the cycle. Prices would tend to fluctuate only if prime costs change, because such changes would affect all firms.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The above general conclusions are not in agreement with all empirical evidence. In particular, these results are consistent with Stigler’s findings, but do not agree with other empirical studies of price flexibility.

The rationalization of the Sylos’s Postulate:

Modigliani argues that the behavioural pattern implied by the Sylos Postulate is the most plausible in the real world. His argument is of no general validity, as he does concentrate on the comparison of Sylos’s Postulate with the optimistic alternative implied by Bain’s Model A, namely, that the prospective entrant expects that the established firms will keep the pre-entry price unchanged.

Modigliani’s argument may be summarized as follows:

The optimistic assumption (on the part of the potential entrant) that existing firms will adopt a strategy of maintaining the pre-entry price, by contracting their output, is a rather foolish expectation.

It implies that established firms will allow the entrant to gain any share of the market that he likes, while their own share is accordingly shrinking and their profits are reduced on two accounts:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) Price would fall, and at this price they would sell less;

(b) Their costs would rise as they would be gradually driven to the increasing part of their cost curve. Furthermore, such an ‘accommodating’ behaviour would create a precedent for further potential entrants. Thus the strategy implied by Sylos’s Postulate, of the existing firms keeping the pre-entry quantity constant, seems a more realistic assumption for the entrant to make. We have discussed the shortcomings of the Sylos Postulate in section I.

To sum up these criticism:

Sylos’s strategy implies a defensive attitude, in that the existing firms give up their initiative for price-setting. Price will be virtually set by the entrant, depending on the quantity he decides to sell in the market. The diametrically opposite strategy of maintaining price is equally unlikely for the reasons given above.

However, a mixed strategy of partly accommodating the entrant and partly allowing the price to fall seems the most likely in the real world. With this combined action some excess profits will still be earned. Furthermore the established firms can undertake an intensive non-price competition which may make the survival of the entrant difficult and discourage further entry.

There is another strategy which may be more profitable for established firms, namely, existing firms may decide to charge the monopoly price over a certain period and then reduce it to the entry-preventing level, or retain the monopoly price for a longer period and allow the price to fall to the competitive equilibrium level Pc as entry occurs. These alternatives have been explored by Pashigian.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally, the alternative strategy of increasing the output post-entry may be more advantageous. This behaviour would imply a price war aiming at the elimination of the entrant, since price would fall below the LAC (that is, below Pc). The adoption of this strategy depends on the financial reserves of established firms (which define their ability to finance their losses) and on the length of time that they expect the price war to last. If this ‘retaliation strategy’ is successfully carried out it will serve as a lesson to future prospective entrants.

Thus the Sylos Postulate, although convenient for the determinate equilibrium that it provides, is by no means the best or the most likely behavioural assumption.

The main shortcomings of Modigliani’s model may be summarized as follows:

Firstly, the model does not determine the individual shares of the firms. Thus the number of firms in the industry is not defined.

Secondly, it assumes scale-barriers are important. This implies that Modigliani does not take into account the typical form of entry in the modern business world, namely entry by an already-established firm in the same or in another industry.

Thirdly, the rationale of the policy of entry-prevention is not discussed.

Fourthly, dynamic aspects arising from growing markets are not considered.

Fifthly, although at some point Modigliani states that the ‘large firms typically set the pace in the market’ and they set the price by applying ‘the full-cost rules of thumb,’ he does not fully explain how the price is defined, nor does he discuss how the interaction of firms with different costs and different shares leads to a stable market equilibrium.

Sixthly, the assumption that the entrant can enter only with the minimum optimal scale is applicable to new firms only. An already-established firm may enter at scales which are profitable for it, although suboptimal for new firms.