Introduction to Classical Macroeconomic System:

The term ‘classical’ was used by Keynes who, by it, referred to all economists who were concerned with macroeconomic questions before the publication of J. M. Keynes General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936.

Modern economists believe that people like A. Smith. D. Ricardo, J. S. Mill etc., belonged to the classical school of thought while A. Marshall, A. C. Pigou, etc., were the neo-classical stalwarts.

The differences between these two economic thoughts were minor, as far as macroeconomics was concerned. That is why Keynes labelled their theory as ‘classical theory’. Here we will follow the Keynesian tradition.

In the classical doctrine, equilibrium level of income is determined by the availability of factors of production. This means that this theory puts emphasis on the supply side for the determination of the equilibrium level of income and thus neglects the demand side.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This supply-oriented classical approach towards income and employment was based on

certain assumptions. These are: (i) there is always full employment of resources; and (ii) the economy always remains in the state of equilibrium, thereby ruling out the possibility of existence of general overproduction and general underproduction.

However, the assumption of full employment is based on another fundamental assumption of the classical theory—the assumption of Say’s Law of Market. Keeping these assumptions in mind, classicists held that a free enterprise capitalist economy always ensures full employment automatically through a mechanism known as wage-price’ flexibility. At the ruling wage rate, everyone is employed. Actual output equals potential output. There is no overproduction and underproduction.

Say’s Law of Market:

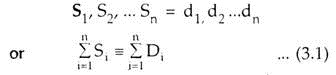

The classical theory of employment is based on Say’s Law of Market. (This law goes after the name of a French economist, J. B. Say.) The essence of the Say’s Law is : “Supply creates its own demand.” People sell goods to get other goods (i.e., barter economy and also money economy). Therefore, the supply of one good involves demand for some other goods. Let us assume that there are ‘n’ different commodities whose supplies are S1, S2 … Sn. Likewise, there are demand for such commodities, labelled as d1, d2… dn. Following Say’s Law, we can say that supply of all goods must equal the demand for all goods, i.e.,

If there are excess supply of any commodity, there must be excess demand for another commodity. Equation 3.1 says that excess supplies are matched by excess demands. Total volume of output does not differ from the level of demand—the act of supplying commodities is simply an act of demanding commodities. J. B. Say argued that the supply of all goods are identically equal to the demand for all goods.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If so, there can be no oversupply or undersupply of goods. Every increase in production made possible by increase in the productive capacity or the stock of fixed capital increases demand exactly by the same amount so that the possibility of overproduction is ruled out. This law, thus, stands out as a denial of the possibility of underemployment equilibrium. Whenever there are lapses from full employment situation, these are then automatically removed by the working of price mechanism (wage-price flexibility).