The following points highlight the four main components of India’s macroeconomic environment. The components are: 1. Economic System 2. Anatomy and Functioning of the Economy 3. National Economic Planning 4. Economic Policy Instruments.

Component # 1. Economic System:

Economic activities are not uniform all over the world. Each economy has its own institutions, laws, rules and regulations that influence what is produced, how it is produced and who gets it.

This is what is actually called economic system. Economic system, thus, is not uniform; it varies from country to country.

Economic system ranges from free market capitalism to planned socialism and their variants.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Capitalism is the product of the Industrial Revolution of the mid-18th century. It is called a market economy or a laissez-faire economy as the institution of ‘market’ or ‘price system’ functions. Socialism as an economic system gained its strength in the first quarter of the last century (1917) when the erstwhile USSR embraced it.

Socialist economy may be called a planned economy as it relies on planning mechanism— instead of market principles—to solve the basic economic problems. Meanwhile, under the impact of the Great Depression of the 1930s, free market capitalism received the severest blow. To salvage the capitalist world, J. M. Keynes recommended the retention of capitalism with governmental interference.

Such economic system is called mixed economy—a halfway house between capitalism and socialism. With the breakdown of the Soviet style socialism in the late 1980s, market principles with little public investment or governmental interference, mainly in social sectors, gained currency all over the world.

Planning mechanism has received a backseat while market principles are put on the driver’s seat. Anyway, even in this latest variant of mixed economic system, we find both planning and market mechanism to operate. The difference is only on the degree of use of planning mechanism.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Economic system that we find today in India can be designated as ‘mixed economy’. When India got her political independence from foreign power on 15 August 1947, she accepted the socialist path of development with the state playing the major role. She adopted planning in 1951 and plans were implemented in the framework of a mixed economy under a strong interventionist state.

Since economists at that time argued that ‘market failure’ was the rule, government had an important and bigger role. But, market mechanism had not been altogether given up as private sector was the biggest sector in terms of its contribution towards the national output. In fact, private sector was given adequate space to operate in keeping with the concept of mixed economy.

However, the growth of India’s private sector was subject to controls and regulations. India’s mixed economy is, thus, characterised by a mixture of planning and market-determined price mechanism. It is an admixture of plan stimulus and control and market efficiency.

Mixed economy of the Indian variety is a planned economy in which public sector has to have an economic plan. In this planning process, the State allocates resources for the development of industry, agriculture, infrastructure, etc. Indian planning strategy of the early years (1951-1990) came to be known as Nehru-Mahalanobis strategy that continued up to 1980s. This planning strategy received a big jolt in the early 1990s when (P.V. Narsimha) Rao-(Monmohan) Singh model of planning strategy was introduced against the backdrop of unprecedented crises—an IMF-World Bank model based on the free market economy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now we will spell out some of the policy instruments that were designed and adopted in the initial years of the planned regime. The most important policy instrument is the Industrial Policy clearly indicating the areas of operation of the state and of the private sector. The first Industrial Policy Resolution of 1948 made it clear that India was going to have a mixed economy.

The principal instruments of 1948 Industrial Policy and subsequent industrial policies announced from time to time are: Industries (Development and Regulation) Act 1951, the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1969 (MRTP), the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) of 1973, and various-other legislative and regulative controls and regulations.

Since ‘market failure’ argument prevailed at that time, the expanding role of the state was the hallmark of India’s mixed economy principle. Participation of the state in various economic activities demanded nationalisation. As a result, the size of the public sector became enormous—its tentacles could be felt everywhere.

But, there occurred a dilution in the mixed economy philosophy in mid-1991 when the reversal of this policy took place. From a controlled regime, India switched over to an uncontrolled regime.

Through privatisation, the state has been withdrawing from various direct production of goods and services except in the areas of basic and social infrastructures, ‘leaving the rest of the production economy to the animal spirits of the private entrepreneurs’.

Component # 2. Anatomy and Functioning of the Economy:

So far, we concentrated on institutional framework of India’s macroeconomic environment which focuses on the role and status of public and private sectors, small and large business houses cooperatives and multinational/transnational corporations, etc. We are now in a position to discuss the structural features of the Indian business environment.

By structure of Indian economic environment we mean an interrelationship between different sectors of the economy i.e., primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. These three sectors constitute the structure of the Indian economy. As economic growth takes place, structural changes occur.

For a complete understanding of the anatomy and the functioning of the Indian economy, we consider the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors. As economic growth occurs, interrelationship among these sectors undergo changes. Such changes are called structural changes.

Economic development brings about a change in the structure of national output and occupations. For instance, at the time of independence, India was basically an agrarian economy as it contributed more than 55 p.c. of its GDP. Now, its contribution has declined to one-fifth (19.4 p.c. in 2007-08) of GDP.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is a sign of structural change. There has also been a change in India’s industrial structure where we find the predominance of consumption goods— mainly durable goods—sector. Economic development, however, necessitates the growth of the capital goods sector.

Employment pattern has, however, not changed significantly over the last 60 years or so. Today (as per 2001 census), slightly more than 56 p.c. of the total population are engaged in the primary sector. One hundred years ago in 1900, it was 72 p.c. or so. This indicates stationary occupational pattern.

These structural changes are accompanied with the change in the structure of productivity. In the industrial sector, labour productivity is higher than the agricultural sector.

India’s structural changes are also associated with changes in the structure of foreign trade. One easily finds that the structure of Indian exports has undergone a remarkable change. There has been a steady decline in the share of agricultural raw materials and allied products in the total exports and, in its place, exports of non-traditional items are on the rise.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Pattern of imports has also changed a lot. Such structural change takes place with the change in the strategy of growth. The share of capital goods in total imports rose from 20.2. p.c. in 1950-51 to 45.5 p.c. in 1956-66.

After then with a change in policy shift, the share of capital goods declined to 15.8 p.c. in 2005-06. Between 1950-51 and 2005-06, the share of raw materials and intermediate goods in the total imports rose from 54 p.c. to nearly 60 p.c. Anyway, the country exports manufactured goods, while imports raw materials, intermediate goods and capital goods.

In describing the anatomy and the functioning of the Indian economy we must not ignore two other sectors—the infrastructure sector and the social sector. As far as India is concerned, these two sectors, upon which the edifice of the economy stands, are rather the neglected sectors.

With the introduction of new economic policy measures in mid-1991, deliberate and conscious efforts are being made to upgrade infrastructure sectors to tone up economic efficiency.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To make economic efficiency a meaningful one, social equity and justice have to be ensured. Because of the existence of private ownership over the means of production, one finds wide inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth.

More than one-fourth of the Indian population now live below the poverty line (27.5 p.c. in 2004-05). Economic development demands an improvement in the lot of vulnerable sections of the population.

This requires huge investment in social sectors like health, education, sanitation and hygienic conditions, etc. The last decade of the 20th century saw an increased expenditure on social sectors and poverty alleviation schemes. The infrastructure and social sectors are not to be addressed seriously here since these two sectors remain outside our syllabus. But, one must not debunk the importance of these two sectors.

Component # 3. National Economic Planning:

Economic planning is often regarded as a technique of managing an economy. When the structure of an economy becomes complex and subject to rapid change and transformation, some sort of advance thinking becomes necessary to resolve that complexity and to prepare the economy for those changes. Such preparation is nothing but economic planning.

The First Five Year Plan was launched in April 1951 to realise the aspirations and hopes of the newly independent Indian people. The dominant economic philosophy at the time was ‘market failure’ and ‘state intervention’. While the idea of a mixed economy was accepted, democratic planning became an integral part of action to create an environment for a richer and more varied life.

During the first four decades (1951-1990) of planning, she registered a satisfactory overall growth rate, but that too fell short of our expectations. Economic planning—coupled with bureaucratic controls, licence and permit restrictions—had created such a mess that the net effect of various economic policies and economic legislations was not indeed a happier one.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Meanwhile, ‘government failure’ in economic functioning became a great source of anxiety. The days of classical capitalism and classical socialism have come to an end. The situation was then crying for a change in the nature of state intervention, nature of the mixed economy of Indian variety.

The Eighth Plan (1992-1997) in this sense was unique as it attempted to manage the transition from the so-called centrally planned economy to the market-oriented economy.

Globalisation-liberalisation-decontrol of the Indian economy brought changes in the nature of Indian planning. As market forces are believed to be the catalysts for economic activities, role and relevance of the planning is being diluted. Today, an integrated approach that considers both planning and market mechanism has been adopted.

It is because of this change in thought— that India’s Eighth Plan may be described as an indicative planning rather than conventional central planning variety. Under indicative planning, markets function—but the state has been assigned certain special responsibilities. Areas of government action or planning have been earmarked.

For instance, human resource development urgently calls for government initiative. It is argued that the most important function of planning is to ‘lobby for the poor in economic policy marking’. Although planning, as understood in 1950-1980s, in India is dead.

In its place, indicative planning has been incorporated in our plans. Development planning continues; only the content of planning has changed. The Eighth Plan is a pace-setter in this direction. We are now in the midst of Eleventh Plan (2007-2012) of indicative variety.

Component # 4. Economic Policy Instruments:

Macroeconomic management calls for adjustment of existing economic policies of the government in the light of changing environment—both in the domestic and international plane. Earlier, we have talked about policy parameters like industrial policy, trade policy, fiscal policy, monetary policy, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is to be remembered that these policy parameters can never be uniform throughout; rather, these are required to be adjusted with the changing situation. It is true that some policies are more effective as well as more appealing than others when the macroeconomic environment of business changes.

For instance, economic policies designed in 1958 by Nehru-Mahalanobis have been reoriented to promote greater efficiency and higher growth in the economy in 1991 as the current economic philosophy all over the globe demands more space for liberalisation, competition, privatisation, globalisation, etc.

Today, the climate is quite different than what it was in the Nehru-Gandhi days. All the Governments have accepted the changes—a change of development policy from import substituting industrialisation (ISI) strategy to market-oriented import liberalisation strategy.

I. Import Substituting Industrialisation (ISI) vs Export-led Industrialisation:

Indian policy- makers placed great emphasis on the policy of import substitution in the early years of planning. The policy of ISI aims at reducing dependence on imports through the supplies of local needs by domestic manufacturing.

The policy of export promotion coupled with the ISI was the foundation stone of Indian planning. Now this is history—since changes in the world economy in the 1970s and 1980s have brought in other policies. The ISI has been given a goodbye and, in its place, a new economic policy based on market principles called import liberalisation along with export-led industrialisation (ELI) strategies has been introduced in 1991.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

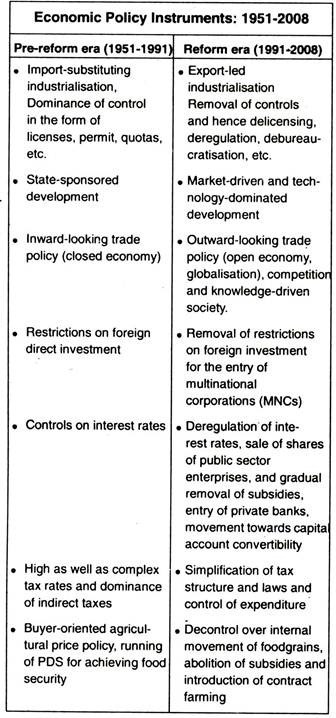

Against these two divergent broad policy measures introduced first in the 1950s (pre-reform era) and latter changed in the 1990s (reform era), Indian policy makers charted out the following sub-set of policies from time to time. Most important among them are industrial policy, agricultural policy, national population policy, fiscal policy, monetary policy, trade policy or export-import (EXIM) policy, employment policy, etc.

II. Industrial Policy:

The first Industrial Policy based on the mixed economy principle was announced in 1948 which demarcated clearly the areas of operation of the public and private sectors. This policy was revised in 1956 which laid greater emphasis on the expanding role of the public sector. This was in keeping with the Mahalanobis strategy of industrialisation embodied in the Second Five Year Plan (1956-1961).

Trade-related ISI strategy of industrialisation demanded control and regulation of the industrial sector. The basic instrument of control was given by the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, 1951, which provided the legislative framework for licensing of industrial investment in the country.

The MRTP Act, 1970—another regulatory mechanism—aimed at controlling the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few big monopoly business houses. The FERA, 1973, was designed to control foreign investment in India. All these controls and regulations were consistent with the broad ISI policy.

India reached the crossroads in 1991 when unprecedented economic crises called for unprecedented changes in economic policies. Making a sharp departure from the 1956 Industrial Policy, the Government of India announced liberalised Industrial Policy on July 24, 1991. Instead of state-sponsored development, the new policy put emphasis on market-led development.

Indeed, this new policy takes a bolder step towards the process of deregulating the economy so that Indian industry becomes more competitive—domestically and internationally. This policy marks a great leap towards privatisation and liberalisation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It envisages disinvestment of government equity. The new policy has laid a red carpet for foreign direct investment. It is in line with the current economic philosophy of the government to liberalise the existing industrial and commercial policies with the objective of increasing efficiency, gaining competitive advantage and achieving modernisation of the economy.

III. Trade Policy:

Trade policy involves measures taken by the government to influence the magnitude and direction of trade. India adopted an ‘inward looking’ strategy or ISI strategy of industrialisation. An elaborate system of government trade controls—such as quotas and tariff restrictions, import licences with a complex system of export incentives—was instituted in 1950s and continued with little changes up to mid-1991. In fact, trade policy became highly restrictive and complex. However, the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi made an attempt at liberalisation, but in a hesitant manner.

Such measures could be termed window-dressing. For genuine reforms based on ‘outward looking strategy’, we had to wait till mid-1991 when Rao- Singh brought in markets and price mechanism in trade policies.

The chief elements of the EXIM policies announced at different times since 1991 are—devaluation of the Indian rupee, convertibility of rupee in current account, abolition of import licensing, reduction in export subsidies, and so on, so forth. Instead of import substitution, current trade policies are mainly governed by globalisation and international competitiveness of Indian goods.

IV. Monetary Policy:

Monetary policy or credit policy concerns itself with the cost (i.e., the rate of interest) and the availability of credit to affect the overall supply of money. The hallmark of the RBI’s monetary policy in the 1950s was that of controlled monetary expansion.

To supplement the process of macro stabilisation and structural adjustment programmes launched in mid-1991, monetary policy has been redesigned. Market-oriented reforms (such as interest rate liberalisation, entry of private Indian and foreign banks, development of alternative system of monetary controls, etc.), are being constantly made since monetary policy measures are continuous.

V. Fiscal Policy:

Another arm of economic policy is the fiscal policy which is concerned with the policy of taxation, expenditure and borrowing. Fiscal policy as evolved over time has resulted in a tax structure with its great reliance on indirect taxation. As it has failed to contain non-plan expenditures, reinvestible surpluses could not be generated. The government then relied on deficit financing and public borrowing.

All these widened fiscal deficit. However, the situation worsened in the early 1990s when fiscal imbalances rose to an unprecedented height. Necessary fiscal policy measures were made, first in mid-1991. Since then fiscal policy has been aiming at promoting a market-led development of the economy. For instance, a continuous effort is being made even today to simplify both the tax structure and tax laws.

In its new fiscal policy, the Government has taken initiative to strengthen methods of expenditure control. Above all, the new fiscal policy aims at improving allocation of resources in terms of market principles. It aims at giving demand stimulus on the one hand, and restraining supply on the other hand by calibrating tax rates.

One finds a large degree of overlap between these various economic policies and their impact upon the macroeconomic variables. Economic policy measures announced by the Government have been presented in a tabular form so as to form a quick idea about macroeconomic management of the country.

Days of Nehruvian socialism characterised by state-sponsored development in an environment of rigid controls, bureaucracy and inward-looking development of the Indian economy are over. The concept of highly centralised planning was the dominant economic philosophy of the Indian economy since 1951 to 1991 (with minor reform measures taken in 1980s).

However, as the development experience of the late 1980s and early 1990s was hardly satisfactory, it called for changes in the economic policy. However, crises and changes in economic policy were not peculiar to India at that time. Even in the Republic of China, erstwhile Soviet Union and the East European countries—where centralised planning was practiced we heard changes in economic policy.

India brought changes in her economic policies in mid-1991 as a part of overall global process. Marketisation, liberalisation, privatisation, deccentralisation and outward orientation of the economy are the essential ingredients of the new economic policy measures introduced by Rao- Singh in July 1991.

Conclusion:

Demise of the Soviet planning system in 1989 and increasing globalisation and marketisation of the Chinese economy launched in 1978 accompanied by remarkable growth performance and above all India’s homemade domestic crises created over the years have brought a change in macroeconomic environment from a controlled or often called over-controlled economy to a liberalised free market-oriented economy.

The early 1990s saw protests – globalisation would cause more harm than benefits. But now it is accepted that globalisation is an irreversible process and India has to be integrated more and more with the world economy. Prosperity lies in it.

The cycle of reforms is yet to stop and thus its full benefits are yet to accrue. At the same time, its costs are not too low. The following chapters will unfold costs and benefits of both pre-reform economic policy measures and reform policy measures and will assess overall economic performance made over these years.